The veteran historian Will Durant claimed that, "Americans are the best informed people on earth as to the events of the last twenty-four hours; [but] not the best informed as to the events of the last sixty centuries."

The study of history can free us from a narrow, blinkered view of the present, seeing the trends of our day as the final word. The English academic C. S. Lewis pointed out that every generation has its blind spots as well as its valid perceptions. He claimed history liberates us from the tyranny of the present and of the recent past: "I don't think we need fear that the study of a day and period, however prolonged, however sympathetic, need be an indulgence in nostalgia or an enslavement to the past... No class of men is less enslaved to the past than historians. It is the unhistorical who are usually, without knowing it, enslaved to a very recent past." Lewis compared the reader of history to a person who has lived in many places. Such a person is "not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village; the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press ... of his own age."

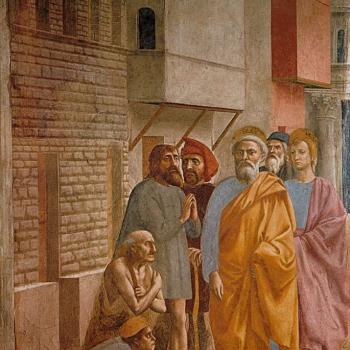

For many, the study of the history of Christianity (or "church history") is seen as particularly dry and dreary. They regard it as irrelevant to the concerns of the present and its study as pointless. Christians often ask why they can't study the Bible without bothering about the history of Christianity. But church history in effect tells us "the rest of the story"; we might even entitle it "Acts chapters 29 and 30": the life and work of John Wesley and Martin Luther, of Francis Xavier and Francis of Assisi, of Patrick of Ireland and Augustine of Hippo and countless others.

To understand how today's church has developed worldwide we need to know something of the great historical creeds, confessions, and doctrines—and of the people who devoted their lives to formulating and securing them. As Timothy K. Jones put it: "The map of God's activity ... is not a blank ocean between the apostolic shores and our modern day. So we need to remember ... the luminaries, risk takers, and movements of the church through the centuries. To neglect them is not only to risk repeating past errors..."

The history of Christianity embraces not only the internal, institutional development of the church, but also its relationship with the surrounding cultures, institutions, movements, philosophies, and religions. Historical study helps us comprehend how we arrived at our present situation. The present has its roots in the past, and knowledge of that past is necessary for any sound understanding of the present. By extension, this also applies to such specific questions as: Why so many Christian denominations? Why do theology, church order, and worship practices differ so widely? Answers are invariably found in the historical figures and circumstances of the multitudinous Christian groups and denominations.

We cannot escape history; we are all caught up in its effects. Its study gives us a deeper understanding of the dynamics of our own civilization. Of course Christianity is not Western, but it has certainly had a transforming impact on Western civilization, so few aspects of our culture can be examined without some understanding of Christianity.

Church history also helps illuminate and clarify Christian theology. Acquaintance with historic theological discussions shows how Christian orthodoxy developed, as Christians of earlier centuries arrived at a consensus concerning fundamental teachings. Their theological thinking and debates can inform and guide Christians today in striving to understand similar doctrines. The doctrine of grace, for example, can better be understood after reading about the controversies involving Augustine, Luther, and Calvin in their time. Similarly, the essentials of Christology can better be grasped through awareness of the theological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries.

Church history also offer examples to emulate or avoid. Ignorance of the many errors in the history of the church only predisposes us to repeat those failures. The British Catholic historian Paul Johnson wrote: "The study of history is a powerful antidote to contemporary arrogance. It is humbling to discover how many of our glib assumptions, which seem to us novel and plausible, have been tested before, not once but many times and in innumerable guises; and discovered to be, at great human cost, wholly false." Christian history can provide warnings about what to look out for and what not to do.

In the history of the church, you will find examples to follow (or not to follow), movements to draw inspiration from (or to avoid), heresies and mistakes to look out for, lessons to heed ("He who forgets his own history is condemned to repeat it. If we don't know our own history, we will simply have to endure all the same mistakes, sacrifices, and absurdities all over again," Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn), questions to think about (whatever question is on your mind, someone cleverer than you has already seen it clearer, thought about it longer, and probably expressed it better).

At the end of the day, "History studies not just facts and institutions; its real subject is the human spirit" (Fustel de Coulange)—and that can't be tidily parceled up and labeled.

8/16/2014 4:00:00 AM