+ Ten Protestant Commentaries in Support of Peter’s Healing Shadow (Acts 5:15): Which Rev. Wright Denied

Charles Henry Hamilton Wright (1836-1909) was an Irish Anglican clergyman. He graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, in 1857, was the Grinfield lecturer on the Septuagint at Oxford (1893–97), vicar of Saint John’s, Liverpool (1891–98), examiner in Hebrew at the University of London (1897–99), and clerical superintendent of the Protestant Reformation Society (1898–1907). He authored a number of books, including The Intermediate State and Prayers for the Dead (1900) and the volume I will be examining, Roman Catholicism, or The Doctrines of the Church of Rome Briefly Examined in the Light of Scripture (London: The Religious Tract Society, revised 5th ed., 1926).

His words will be in blue. I use RSV for biblical citations.

***

In favour of the veneration due to relics, the case of the man raised up to life on touching the bones of Elisha (2 Kings xiii. 21) is quoted. But that incident, if part of the original book, stands completely isolated, and even that miracle did not lead to the worship of the prophet’s bones. (p. 190)

First, Rev. Wright casts doubt on whether the passage is actually part of Holy Scripture, sinking to the methodology of the most radical biblical critics (up to and including atheists), who habitually are suspicious of the text of canonical Scripture, rather than holding to biblical inspiration, inerrancy, and infallibility, as consistent Christians of all stripes do. This is the length that this Anglican will go in order to reject Catholic, biblical teaching. It’s very telling, isn’t it?

Then in his next desperate move to avoid the clear implication of the text, he says that the occurrence was “completely isolated.” Whether something is mentioned once or a hundred times is irrelevant as to whether it is inspired (as part of God-breathed revelation) or true. The Annunciation, for example, was a one-time event in Scripture: mentioned only in Luke, and that was the announcement of the incarnation. This is simply an unworthy debate tactic. Moreover, whether veneration of Elisha’s bones was mentioned in this place or occurred in history (whether recorded or not) is irrelevant to the conclusions that we draw from what happened. It is what it is.

Then he uses the usual tactic of irrationally and cynically collapsing all reverence and veneration into “worship” so that it sounds like idolatry. But even his own citation, drawn from the Council of Trent uses the phrase “veneration and honour.” This is all standard playbook anti-Catholicism: fundamentally silly and a gross misrepresentation of what Catholics believe. We believe that physical matter can be a conveyor of spiritual grace. This is the foundation for the use of relics (objects associated with saints) and sacramentals (sacred or devotional objects).

Veneration of the saints and their relics is essentially different from the kind of worship or adoration reserved for God alone, in that it is a high honor given to something or someone because of the grace revealed or demonstrated in them from God. The relic (and the saint from whom it is derived) reflects the greatness of God just as a masterpiece of art or music reflects the greatness of the artist or composer. Therefore, in such veneration, it’s God being honored. The saint or his or her relics reflect God’s grace and holiness. To worship as divine a saint or relic is not following Catholic teaching, which fully agrees with Protestantism with regard to the evil of idolatry.

In the passage about Elisha’s bones, from 2 Kings, matter clearly imparts God’s miraculous grace. That is all that is needed for Catholics reasonably and scripturally to hold such relics in the highest regard and honor (veneration). It is not necessary for the entire doctrine of veneration to be spelled out in the verse, only the fundamental assumption behind it (matter can convey grace), which is the basis for the Catholic belief and practice. We are physical creatures; God became man, and so by the principle of the incarnation and sacramentalism, the physical becomes involved in the spiritual. What we believe about relics is based on these biblical presuppositions.

Many Protestants (including Martin Luther himself, Lutherans, Methodists, Anglicans, Churches of Christ) accept this principle with regard to the waters of baptism, which, so they hold, cause spiritual regeneration to occur, even in an infant. That is, again, matter (water) conveying grace (regeneration). And so Elisha’s bones raised a man from the dead. Why would anyone wish to downplay or minimize that? It’s because they are irrationally unbiblical.

The touching of the hem of Christ’s garment (Matt. ix. 20) was a sign of faith in Christ, but not a proof of any virtue in His clothes. (pp. 190-191)

Again, he misses the fundamental point. The woman did have commendable faith. But it’s not the clothes themselves. It’s the fact that they were connected with Jesus. They conveyed grace and healing for that reason and no other. Let’s do a quick thought experiment. Imagine a scenario in which somehow we could verify that a shirt was worn by Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself and came into the possession of Rev. Wright. Do you think he (or anyone) would make a rag out of it, for use in cleaning a cow stall or grease from a car? I think not. It would be reverenced and cherished for its association with Christ. That’s 90% of the way towards the Catholic understanding of a relic.

Protestants enjoy visiting Israel as much as anyone else. And they reverence the holy places there, and do things like touch the star where Jesus was born or the white hill underneath where He was crucified. That’s reverence for holy places. They may not think that they literally receive grace in doing so, but it’s close. They wouldn’t ever consider for even a moment, bulldozing any of these holy places and making a parking lot or a McDonalds. Yet they inconsistently fight against the idea of relics and veneration given to them. Part of the antipathy, no doubt, is because many have this false notion that we are worshiping them as if they are equal to God Himself. It’s not true. They might represent or be associated with God or a saint, but that doesn’t make them equal to them. It doesn’t make them idols. They’re neither replacing God nor placed above Him.

Extraordinary was the faith of the people in Peter after the awful deaths of Ananias and Sapphira. But although they imagined Peter’s shadow could heal the sick, the text does not state that as a fact (Acts v. 15, 16). (p. 191)

This is very interesting. In his rush to immediately discount any Catholic biblical argument in favor of relics, he is led to the conclusion that this didn’t refer to healing as a result of Peter’s shadow. But even his own Protestant commentators massively disagree with him. They generally hold that healings likely did occur. I provide ten examples below.

Acts 5:12-16 Now many signs and wonders were done among the people by the hands of the apostles. And they were all together in Solomon’s Portico. [13] None of the rest dared join them, but the people held them in high honor. [14] And more than ever believers were added to the Lord, multitudes both of men and women, [15] so that they even carried out the sick into the streets, and laid them on beds and pallets, that as Peter came by at least his shadow might fall on some of them. [16] The people also gathered from the towns around Jerusalem, bringing the sick and those afflicted with unclean spirits, and they were all healed.

Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers: (15) Insomuch that they brought forth the sick . . .—The tense implies habitual action. For some days or weeks the sick were laid all along the streets—the broad open streets, as distinct from the lanes and alleys (see Note on Matthew 6:5)—by which the Apostle went to and fro between his home and the Temple.*That at the least the shadow of Peter . . . .—It is implied in the next verse that the hope was not disappointed. . . . Christ healed sometimes directly by a word, without contact of any kind (Matthew 8:13; John 4:52); sometimes through material media—the fringe of His garment (Matthew 9:20), or the clay smeared over the blind man’s eyes (John 9:5) becoming channels through which the healing virtue passed. All that was wanted was the expectation of an intense faith, as the subjective condition on the one side, the presence of an objective supernatural power on the other, and any medium upon which the imagination might happen to fix itself as a help to faith. So afterwards the “hand, kerchiefs and aprons” from St. Paul’s skin do what the shadow of St. Peter does here (Acts 19:12). In the use of oil, as in Mark 6:13, James 5:14, we find a medium employed which had in itself a healing power, with which the prayer of faith was to co-operate.Benson Commentary: . . . in order that, if they could neither have access to Peter, nor he come to them, at least the shadow of him passing by might overshadow some of them — Though it could not reach them all, and they had faith to believe this would be the means of healing them. And it is probable that they were not disappointed, but that some, at least, were thus healed, as the woman mentioned in the gospel was, by touching Christ’s garment. According to their faith it was done unto them. And in this, among other things, the promise of Christ, (John 14:12,) The works that I do, shall ye also do, and greater works than these, &c., was eminently fulfilled. And if such miracles were wrought by Peter’s shadow, we have reason to think some were wrought in some such way by the other apostles; as by the handkerchiefs from Paul’s body, Acts 19:12.

Expositor’s Greek Testament: The further question arises in spite of the severe strictures of Zeller, Overbeck, Holtzmann, as to how far the narrative indicates that the shadow of Peter actually produced the healing effects. Acts 5:16 shows that the sick folk were all healed, but Zöckler maintains that there is nothing to show that St. Luke endorses the enthusiastic superstition of the people (so J. Lightfoot, Nösgen, Lechler, Rendall). On the other hand we may compare Matthew 9:20, Mark 6:56, John 9:5, Acts 19:12; and Baumgarten’s comment should be considered that, although it is not actually said that a miraculous power went forth from Peter’s shadow, it is a question why, if no such power is implied, the words should be introduced at all into a narrative which evidently purports to note the extraordinary powers of the Apostles. . . . as Blass says, Luke does not distinctly assert that cures were wrought by the shadow of Peter, although there is no reason to deny that the Evangelist had this in mind, since he does not hesitate to refer the same miraculous powers to St. Paul.

Henry Alford, Greek Testament Critical Exegetical Commentary: We need find no stumbling-block in the fact of Peter’s shadow having been believed to be the medium (or, as is surely implied, having been the medium) of working miracles. Cannot the ‘Creator Spirit’ work with any instruments, or with none, as pleases Him? And what is a hand or a voice, more than a shadow, except that the analogy of the ordinary instrument is a greater help to faith in the recipient? Where faith, as apparently here, did not need this help, the less likely medium was adopted.

[John] Calvin’s Commentaries: the apostles were endued with such power for this cause, because they were ministers of the gospel. Therefore they used this gift, inasmuch as it served to further the credit of the gospel; yea, God did no less show forth his power in their shadow than in their mouth.

F. F. Bruce, New International Commentary, Book of Acts (revised version, Eerdmans, 1988, p. 109): Peter’s shadow was as efficacious a medium of healing power as the hem of his Master’s robe had been. No wonder that the people in general sounded the apostles’ praises and that the number of believers increased.

C. Peter Wagner, The Book of Acts: A Commentary (Baker, 2008): Apparently Peter, at the time, was ministering in the role of what some would call a “faith healer” today. Others were doing miracles as well, but it seems that Peter had a special anointing.

David W. Pau, Baker Illustrated Bible Commentary, Acts: [Peter’s] shadow reminds one of Jesus’ own magnificent power (Luke 8:44) . . .

Eckhard J. Schnabel, Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Zondervan Academic, 2016, p. 293): Some, not all, of the sick were healed through Peter’s shadow . . .

Ben Witherington, The Acts of the Apostles (Eerdmans, 1998, p. 227): It is not clear whether Luke also holds this belief, but v. 16b probably suggests he did (cf. Acts 19:12 [Paul’s handkerchiefs]).

Aprons were, indeed, on one occasion brought from the body of Paul ( Acts xix. 11 , 12); but if ever extraordinary miracles were required, it was at Ephesus, the great stronghold of magical arts. (p. 191)

I see. It’s almost like Rev. Wright begrudgingly concedes that a relic-like miracle did occur; but only “on one occasion”, mind you! Then he tries to irrationally water it down or minimize its strength as a Catholic proof for relics by making the odd comment that it was especially needed at Ephesus. That’s simply an irrelevant diversion; what is called a non sequitur. Rev. Wright has not succeeded in disproving the fact that the principle behind the Catholic belief in relics and their power is clearly taught in the Bible. He belittles, attempts to minimize, is dismissive, and doesn’t even seem to take the topic seriously (all traits very common in anti-Catholic polemics), but he doesn’t disprove our view; not even within a million miles.

*

***

*

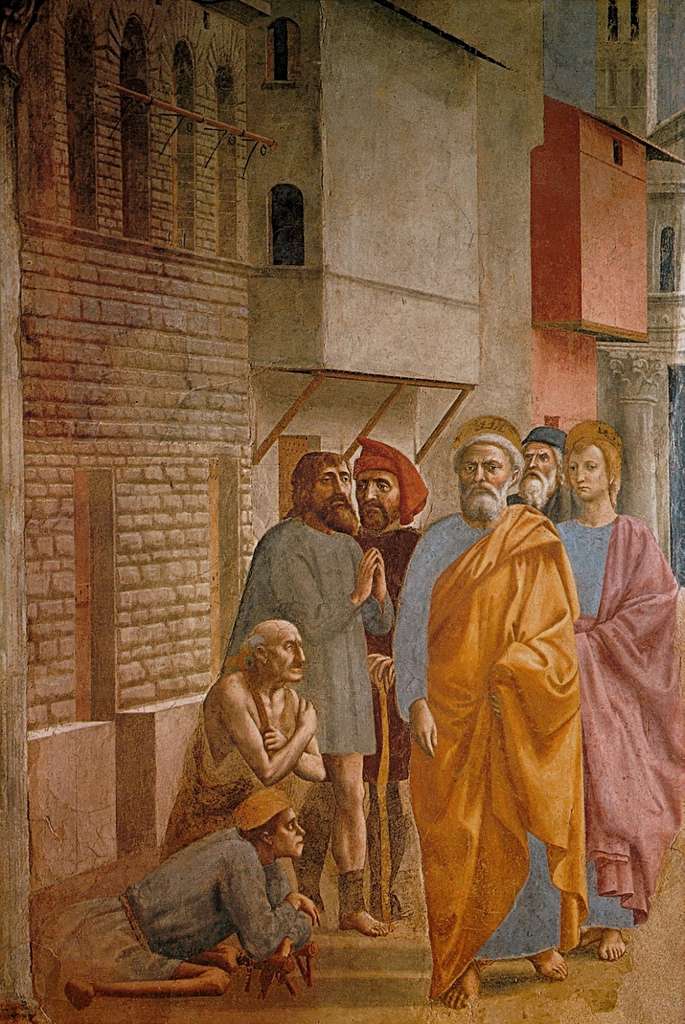

Photo credit: St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow (1425), by Masaccio (1401-1428) [public domain / Get Archive]

Summary: I reply to several weak mini-arguments from the Anglican, Charles Henry Hamilton Wright (1836-1909), against the biblical conception of the spiritual power of relics.