Do you believe God is a God of truth? Does He know it, keep it, and guard it? Does He wait for us to tell Him what it is?

I wrote last week about the Last Judgment, at which the books of our deeds will be opened. God knows everything that has happened. No other human being will be accusing us at this great judgment. Each of us will give an account of himself—but if you want to point a finger at someone else, you'll be out of luck at the Last Judgment. That event will be run by Jesus Christ, and it will operate on godly principles.

God doesn't need cues like pointed fingers. When we are before Him at the Last Judgment, He won't be interested in whatever evil we think others did. The converse is true as well: He won't listen to others speak evil about us. God doesn't give an ear to accusation. He doesn't let falsehood or any other form of evil sit at the table with Him. And neither should we.

I'm not sure we fully grasp what that means about the way we should live. Seeking to deal with others through accusation is wrong. This doesn't mean that it's wrong to truthfully accuse someone who has committed a crime. It means that using accusation as a way of intimidating our family, friends, or co-workers, or of heaping condemnation on individuals or groups for political or religious purposes—using it as a way of life in our dealings with men—is a form of evil.

When real atrocities or crimes have been committed, it's not wrong to call that out. But framing whatever you disagree with in an accusatory narrative is an abuse of the concepts of truth and the justifiable exposure of evil. When you act from a posture of accusation, your tales aren't a basis for making things right or moving forward. Typically, they suggest only a "solution" of unrequitable anger and/or visceral rejection of a human or a group of humans—which is a terrible abuse of the godly idea of indignation against wrongs.

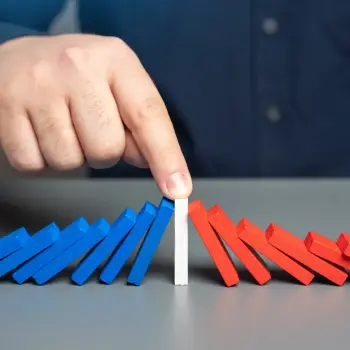

If we try to compromise and meet accusation halfway, we are caught in a downward spiral in which we have no handhold or leverage. The tales told from a posture of accusation can only be repudiated on principle. This is why wise leaders from time immemorial have "just said no" to letting a culture of accusation take over their enterprises. It's why forgiveness has power, no matter what the injury, but holding grudges doesn't: because we can't bargain with evil; we can't use it or get the upper hand over it; we can't prevail if we are locked in a battle with it on its terms. Our hope lies in rejecting it absolutely on principle.

It is the stronger and better way, to simply reject third-party accusations that will shape our perceptions negatively about others. This doesn't make us foolish—although some accusations could be valid, of course—it makes us wise, strong, and clean inside. Accepting accusatory comments about others isn't about them, it's about us. Do we give our minds over to narratives about the supposed evil of others? Or do we trust God's principles and promises more than that?

When we get to that Last Judgment, we aren't going to be asked what Mitt Romney or Barack Obama did in life. We're going to be asked what we did about the tales told of them for political purposes. Someone else will be asked why he or she created a political advertisement accusing Romney of killing a steelworker's wife. You and I will be asked what we did—what decision we made for the spiritual health of our minds and hearts—when we were confronted with that ad. Did we reject the evil accusation on principle, and decline to give it a home in our thoughts?

How about the accusations made in the blogosphere that Obama has been deceptive about his religion, or the tabloid gossip suggesting that his marriage is falling apart? Are we giving our minds over to that stuff, or are we rejecting those thoughts on principle? Someone else will be asked at the Last Judgment about his or her role in launching these tales. But for the health of our own minds, it is no better to entertain accusations that the President has pretended to be a Christian while actually being a Muslim than it is to accept accusations that Mitt Romney, because he is a successful businessman, caused a woman's death.

What if some of the accusations made against other people are true? It's one thing when we're talking about crimes and the justice system. Credible accusations about crimes ought to be given due process of law. But when the accusations are crafted to be persuasive but basically non-actionable—the point is to persuade people that they know something bad about the subject, to get evil thoughts into people's minds—I submit that we are still right to refuse, on principle, to form a bad judgment on those terms.

Some tales can be parsed and rejected because the world doesn't work that way (e.g., the contrived accusation against Romney); other tales may not be parsable in that manner, but should still be rejected because it does us no good to accept them as part of the narrative in our minds. I've found it to be consistently true that I don't need to consider accusatory tales about others in order to make good decisions. There is no positive purpose for an accusatory mode of thought or communication.