We have seen massacre after massacre, here and elsewhere—and now in Newtown.

Earlier this year, there was the devastation of Hurricane Sandy and a typhoon in the Philippines, to which we can add last year's Sendai tsunami and many more natural disasters.

For centuries we have suffered sectarian, nationalistic, imperialistic, and totalitarian wars, with no prospect in sight of them coming to an end: World Wars I and II, Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Algeria, Palestine, Syria, and on and on.

Some of us have been incredibly lucky. We have not been directly affected by those events. Nevertheless, all of us experience personal tragedy. Eventually, if not already, someone we love will die, perhaps inexplicably or in great pain. If they have not already, many people will experience difficulty or failure in their career through no fault of their own. Many marry with great hope only to be crushed by eventual marital disaster; others have children who began their lives with great promise but who then turn on their parents or simply fail themselves, accomplishing little or nothing. Disease will strike us down or it will strike down those we love.

It is easy to find pain in our lives and the lives of our neighbors.

Faced with pain and horror it is tempting to look for an explanation. But we must take care when we do so. What pains us is less painful if we have an explanation, which is probably one reason we look for explanations. And there are explanations of many pains. But we ought not to make genuine horror, such as the horror of Newtown last week, less horrific by explaining it away. If we do, then we also reduce its evil, which would be unjust to those who suffered its horror.

What happened was evil and ought to be recognized as evil. It ought to be understood to be beyond understanding. That doesn't mean that we must seek recrimination or find blame. In fact, both of those refuse to see evil as beyond understanding and, instead, create an understanding of it by placing blame.

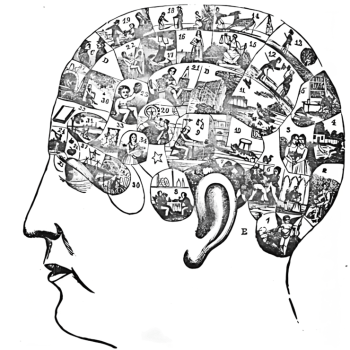

We can and should recognize horror without feeling that we can put our finger on its cause. That, in fact, is precisely one of the reasons the event in question is horrific: we can see no cause, even if we can name its agent. There is evil and it is beyond our ken.

But even if human beings cannot understand why a particular evil occurred, if God exists, how can there be these evils? Surely a loving God would not allow them to happen. Surely, we cry, God could at least decrease the amount of evil in the world.

But from what vantage point can I make that judgment? Even if God has the power to decrease the amount of evil in the world (natural and moral), and Mormon theology at least suggests that he might, I have no way of judging that there is, indeed, a possible world with less evil in it. I cannot know whether my demand is even possible. Imponderables make my question impossible to answer. My question marks a cry of my heart, a plea to God rather than a question with a rational answer.

Whatever the case with the amount of evil in the world, it is clear that the Father could not get rid of the possibility of moral evil without also getting rid of human agency. Except as a cry of the heart, an exception not to be dismissed lightly, the desire to eliminate the possibility of evil is implicitly also the desire to eliminate the possibility of meaningful agency.

As LDS thinkers remind us from time to time, most recently in Givens and Givens's The God Who Weeps: How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life, Mormon scripture teaches that pain and sorrow are not only mortal experience. They are also the experience of God. In the revealed book, Moses, the prophet Enoch has a revelatory encounter with God:

And it came to pass that the God of heaven looked upon the residue of the people, and he wept; and Enoch bore record of it, saying: How is it that the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains? And Enoch said unto the Lord: How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity? . . . The Lord said unto Enoch: Behold these thy brethren; they are the workmanship of mine own hands, and I gave unto them their knowledge, in the day I created them; and in the Garden of Eden, gave I unto man his agency; and unto thy brethren have I said, and also given commandment, that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood . . . . (Moses 7:28-29, 32-33)