Editor's Note: This is the fourth post in a series telling the stories of significant black Mormons in history. Read earlier posts:

A father of an anorexic daughter said that she, caught in the bondage of her disease, was the least able to tell her own story. She would distort it just as she distorted the image she saw in the mirror. Who, then, would be able to tell her story truthfully? Her counselor? Her family? Her boyfriend? Nobody?

The answer is that each of us is a unique mystery. At some point in our eternal maturing, we realize that we can never really know another person, even those with whom we are most closely associated. Though we may be close enough to them to have similar thoughts and even matching days, we cannot enter their minds, we cannot capture their pasts, we cannot define or possess them. We ourselves are constantly progressing in understanding our own reactions to the world around us, our relationships, our impulses, our inner conflicts and yearnings.

This is particularly important when someone who thinks they possess another person presumes to speak for them. In the case of Green Flake, given at age ten as a wedding gift to James Madison and Agnes Love Flake (along with another slave, Liz) in 1838, we find various versions of his story, depending on who's telling it. The white Flakes tend to tell Green's story starting with his baptism (April 7, 1844), claiming that Green and all the Flake slaves were freed when the Flakes joined the LDS Church—though Green and two other Blacks, Oscar Crosby and Hark Lay, are listed as "colored servants" on the monument to the vanguard pioneers. The use of the word "servant" rather than "slave" is significant. It provided a semantic way to avoid acknowledging that there were slaves in Utah. Brigham Young's important talk to the legislature in 1852 is titled "An Act in Relation to Service"—though it mentions slavery outright.

Green's own descendants start his biography early in his life. His granddaughter, Bertha Udell, told family historian John Fretwell:

Green said that the reason why they kept him from his mother or family was because if they love one another too much, if one was sold they could pine and worry so much . . . they could run away and search for each other. The masters didn't want to lose a valuable slave, so he would set mean dogs after them and whipped [them] when they were caught. That is why Green Flake was kept away from his mother and told he was an orphan. . . . As a child, he grew up with other colored children about his own age and he was cared for by different women in the Negro Quarters. . . . He learned early that he was a slave.

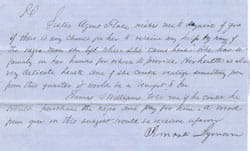

Lucile Perkins Bankhead, a great-granddaughter of Green Flake, says in her oral history (recorded for BYU's Charles Redd Center by Alan Cherry) that Green never was freed. Other members of the black side of the Flake family claim that Brigham Young emancipated their ancestor in 1854. That seems a reasonable claim. Clearly, Green was considered a slave when Brigham Young received a letter from Amasa Lyman, speaking for the widow Agnes Love Flake. Her husband had been killed in California by a mule kick. Agnes had followed him to San Bernardino, but found only poverty there. Lyman wrote:

Sister Agnes Flake wishes me to inquire of you if there is any chance for her to receive any help by way of the negro man she left when she came here. She has a family on her hands for which to provide. Her health is also very delicate health and if she could realize something from this quarter it would be a benefit to her. Thomas I. Williams told me if he could, he would purchase the negro and pay for him. A word from you on this subject would be received a favor.

To be clear, this assumed that Green Flake was still a slave and asked that he be sold and his price sent to Agnes. Brigham Young replied that he didn't know where Green Flake was. In fact, Young had given the former slave several acres of land in the Cottonwood area. Green was married by this time, though his wife, Martha Crosby, was also considered a slave. Both Green Flake and Martha worked for the Crosby family until Martha's master decided they had paid "a fair price for a colored girl" (Ronald Coleman's "History of Blacks in Utah," 39). Soon after Brigham Young discreetly declined Lyman's request, Green and Martha conceived their first child, Abraham, who would soon be followed by a daughter, Lucinda.