“Religion Behind the Scenes” spotlights the less discussed, but no less crucial, tasks that keep religious communities running, and the people who make it all happen.

One of the very last things Benjamin Franklin ever penned was that famous line, “In this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.” All of us die, and whether you’re a Christian, a Jew, or a Hindu, there are funeral rites that facilitate the deceased’s transition from this world to the next.

When it comes to death and funerals, like other religions, Islam has its own rites and procedures for dealing with the deceased. Muslims have a very specific set of practices associated with preparing oneself for death, readying the deceased’s body for burial, and holding an appropriate Islamic funeral. But what do all these things look like in Islam? And how do they differ from the funeral customs of other religions. What happens to a Muslim who cannot afford a funeral or proper burial? And who is responsible for conducting such rites in the Islamic tradition?

In this eye-opening installment of Religion Behind the Scenes, we talk with Dr. Salman Masud—a Muslim anesthesiologist who focuses on orthopedic anesthesia for pediatric patients, and who has spent years tending to the dying and their bereaved family members. Dr. Masud is one of the founders of Khadeeja Cemetery—an all-Muslim cemetery in the state of Utah. And in our interview, he answers the aforementioned questions about death in Islam and how all human beings should approach life and the life-hereafter.

Tell me a bit about preparations for death that take place when a Muslim knows that death is immanent. What happens? What are they encouraged to do?

A person who is dying—who clearly shows signs that death is near—will typically lie on their right side, facing the Qiblah (or Kaaba) in Mecca. If it’s too uncomfortable for the person to lie on their side, it is permissible for the person to lie on their back with their feet towards the Qiblah.

Family members will often recite verses from the Holy Qur’an to the dying person. Someone should also say Talqueen—“I testify that there is none worthy of worship but Allah and I testify that Muhammad is His servant and His messenger.” Saying this encourages the dying person to repeat the Shahaadatain, so that they die with the name of Allah on their lips. It is “Makrooh” (or disliked) to recite the Holy Qur’an near the deceased person’s body after death and until after Ghusl (or the ritual bathing of the deceased) had been completed—since nothing “unclean” should be allowed near the Holy Qur’an.

Once the departing person utters the Kalimah, everyone present should remain silent. The dying person shouldn’t be drawn into any worldly discussions but, if he discusses anything “worldly,” then the Talqeen should be repeated again.

Once the person has passed, the family pray: “O Allah! Forgive me and him [or her, if the deceased was a female] and grant me a good reward after him [or her].” If there are those who are particularly grieved by the passing of the deceased, they might pray: “To Allah do we belong and to Him shall we return” or “O Allah! Reward me in my affliction and requite me with something better than this.”

Does the person who takes care of the body of a deceased Muslim have to have some kind of special training—some kind of “certification,” per se? Is there a role for clergy (or imams) in what you do?

In the Sunni tradition, every adult Muslim should be able to lead prayer (or salah), conduct a marriage, and conduct a funeral. However, the 12-15% of Muslims in the world who are part of the Shia tradition must be from a school. You can compare it with the Catholic Church. Those who perform their rites must be ordained, right? So, the Shia are like that. There has to be somebody who is from a particular school to conduct a funeral. But most Muslims are Sunni, and any member could prepare a body and conduct the funeral. And, in fact, this is what we are teaching our kids who over 21. We hold classes two or three times a year, encouraging them to learn how to do this—and we certify them to perform this work.

What customs are there in preparing the body (such as washing & shrouding the body, special prayers, etc.)?

In Islam, the deceased are washed prior to their burial. The person performing the washing should start the process of Ghusl (meaning “washing”) by saying: “Bismillah” (which means “In the name of Allah”).

While Islamic Societies often have personnel who can bathe the deceased, it is recommended (in Islam) that an adult male should be bathed by his father, son, or brothers. Similarly, an adult female should be bathed by her mother, daughter, or sister. We encourage adult children that, even if they don’t wash their parent’s body themselves, at least be present. Your parents have done so much for you, being present is the least you can do, right? You need to be part of that process. If no immediate family member is available then any close relative can carry out the Ghusl (male for male, and female for female).

While the deceased is being washed, their “private parts” (or Auwra) are constantly kept covered—as a means of showing respect to the deceased.

The person performing the Ghusl must themselves be in a state of ritual purity and in a state of Wudu (ablution). It is makrooh (disliked or discouraged) for a woman who is menstruating or is bleeding because she recent gave birth to perform Ghusl. After performing the Ghusl for the Mayyit (the deceased), one is not required to take a shower. (While it is not mandatory, a shower before and after completing Ghusl is common and encouraged.) Technically, Wudu would suffice, except if the person who performed the Ghusl encountered major impurities in the process of washing the deceased.

The Ghusl or washing is traditionally done three times. However, if after those three washings the body is not entirely clean, the deceased be washed more—but the body should be washed an odd number of times.

Once Ghusl is completed, the “Kafn” (or “shrouding”) of the deceased takes place. For a male, you use three pieces of cloth: the Lafafah (a long outer sheet that will cover the entirety of the deceased person’s body), an Izaar (a second sheet which can cover the body from the top of the head down to the feet), and a Qamees (a sheet which covers from the neck to the feet, akin to a nightshirt). For a female, you use five pieces of cloth: the three previously mentioned ones (used on a male), and then two others—a Khimar or Orni (which covers her head and hair) and a Khirqa or Sinaband (that is to be tied around her breasts, basically covering from under her armpits down to her thighs).

Nothing is to be written on the fabric of the Kafn, nor should you insert any written items, any pictures, or any personal items of any kind.

Using a man to explain the process, you first lower the body gently onto the Kafn and cover the top of the body down to the calves with the folded portion of the Qamees. Then remove any material used for covering the Awrah/Satr (or private area) during Ghusl.

Next, you might apply perfume on the head and beard and rub a camphor mixture on the places of Sajdah (meaning on those parts of the body that touch the ground during salah, or prayer: the forehead, nose, both palms, and on the top side of the feet).

Finally, you fold onto the top of the body the left flap of the Izaar, and then on top of that the right flap. Then, fold the Lifafah in the same manner. Remember that the right flap must always be on the top. Lastly, fasten the ends of the Lifafah at the head, feet, and around the middle with strips of cloth.

What traditional funeral customs are there for practicing Muslims?

Salat al-Janazah, or the Funeral prayer, is Fard Kifaayah (meaning it is a communal obligation). If only a few people in the community perform the act, the entire community is absolved of the obligation to do it.

Unlike during Salah, there is no bowing or prostration in Janazah. It is performed while standing. The funeral prayer consists of four Takbeeraat (ʾAllāhu ʾakbarᵘ, meaning “God is the greatest”): first, Thana (the glorification of Allah), second, Durood (salutations upon the Prophet), third a Masnoon Dua (a prophetic supplication) for the deceased, and fourth, a Salam or two (supplications of peace concluding the prayer). All of these are said silently. It is only the Imam who should call out Takbeeraat and Salaam aloud.

It is recommended that those who attend the burial service be males; and that women visit the cemetery after the funeral has concluded. This isn’t mandatory, but customary in many parts of the world.

How quickly are the deceased buried (and why expeditious burials)?

Usually within 24-hours, but often more quickly than that. We’ve done funerals as quickly as 2-hours after the person died. Islam teaches that funerals should be arranged without delay. The Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) said, “If a person passes away, hasten him to his grave and do not keep him away” from it. So, to delay the funeral in order to wait for latecomers to arrive (so that the size of the congregation present will be increased) or to transport the body over long distances (which would delay the burial) are considered undesirable things. If the family wants to wait for a loved one to arrive the next day, because they can get a flight or something, that’s fine. But the preferred method is to bury as quickly after death as possible.

You see, once the body is buried, people can begin to heal. The longer you wait to bury the deceased, the longer it takes to start the healing process. So, the quick burial (in Islamic tradition) is a kindness to the family. It helps them to get closure more quickly. The longer the body stays unburied, the whole thing—the grief—kind of continues to build up. So, you’re actually being kind to the family by taking care of this as expeditiously as possible.

Is there a proper and improper (or unacceptable) way to burry a practicing Muslim (e.g., cremation, embalming, or other taboo practices)?

We do not cremate, nor do we embalm. You see, the body is a trust—loaned to us from God. For example, if you check out a book from the library, you don’t “tattoo” that book, you don’t deface it. You have to enjoy the benefit from the borrowed book and then return it in the best condition possible. This is not my body because I didn't pay for it. It belongs to Allah.

The word “religion” comes from the Latin, “religio”—which means to “tie” or “bind.” It means we have a “tie” to the Creator, and He to us. The equivalent word in Arabic means that we are indebted to God. So, for example, if I lose my eye in an accident, I would get a glass eye—because they can’t transplant a new eye. Even if I offer the surgeon 10 million dollars, they can’t give me a new eye. My eye was a gift to me. I didn’t buy it. And I can’t pay to buy a new one. It was given to me on loan by God, and I am to take care of it, treat it with reverence and respect, and return it to Allah in the best condition I possibly can. Cremation and embalming don’t really show respect for the body. The body should be buried so that it can return to the earth in a natural and peaceful manner. So, embalming is not typically done in Islam, except if required by state or federal law.

Also, applying makeup to the deceased and holding a viewing is not traditionally done.

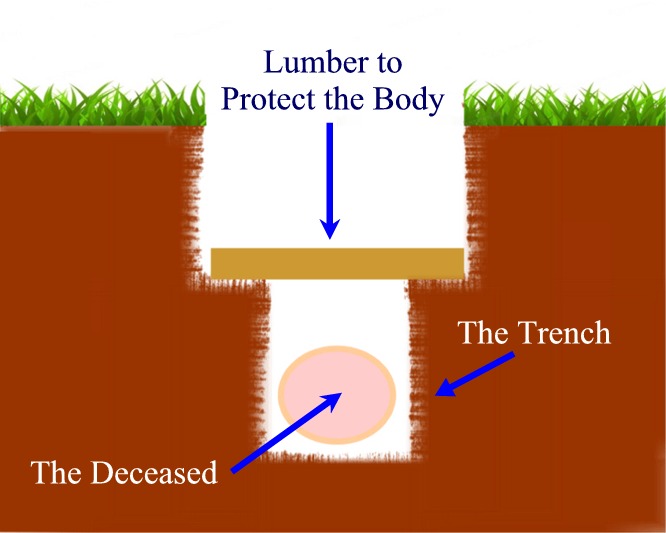

Before lowering the body into the grave, it is Sunnah (or tradition) to turn it onto its right side so that the deceased person faces the Qiblah (or Kabbah). Those placing the deceased in the grave should also ensure that the strips of cloth tied at the head, side, chest, and leg side are untied.

Once the body is placed in the grave, in some countries or cultures, a layer of wood will be place on top of the body so that the deceased’s body is somewhat protected from the soil. We don’t do that at the Khadeeja Cemetery. It is not formal Islamic practice, but just a tradition in some areas.

All who are present should participate in filling the grave with a least three handfuls of soil, as they recite, “From the earth did We crate yo7, and to it We return you. We bring you out once and from it shall again.”

Large monuments, excessive sized tombstones, inscriptions of the Holy Quran on a headstone, and enclosures (like mausoleums) are not recommended. Structures on the grave have been emphatically denounced by the Prophet (PBUH). The memorial to a human should not be greater than a memorial to God.

In cemeteries you commonly see written on a headstone “Here lies beloved father” or “beloved mother.” It is a simple statement. As an academic, when you start your career, you might have a 5-page vita, CV, or resumé. Near the end of your career, your resumé will be 20-30 pages in length. It gets so long, no one wants to read it—so you create a one-page version. Finally, when you die, it becomes a one-liner. What’s the lesson? We fill our lives building a long resumé, titles, and accomplishments. When you die, none of those matters. So, never put your work before your family or the things that matter. What will the one-liner on your headstone be? When all is said and done, will it be said of you that you were a “beloved father” or “beloved husband”? A “devoted disciple” of God? When you are dead, will anything else matter? A large or elaborate headstone won’t get you into heaven. I’ve tried to live my life by that philosophy.

Are shroud burials more common than casket burials? Is one preferable and, if so, why?

A casket is hardly ever used in a Muslim funeral. We use vaults because it's city code. But casket burial typically doesn't exist among Muslims. Whether rich or poor, we typically do shroud burials, not casket burials. The ideal is to be buried in a shroud and then directly in the soil. Local or state laws might require a vault, so we go along with the local laws. Khadeeja Cemetery is near the Jordan River, so our water table is high. Thus, we have to use burial vaults. We actually put some dirt into the vault, as it will help with decomposition. But casket funerals are rare in Islam. Almost everyone is simply buried in a shroud—and that’s what’s preferred where legally possible.

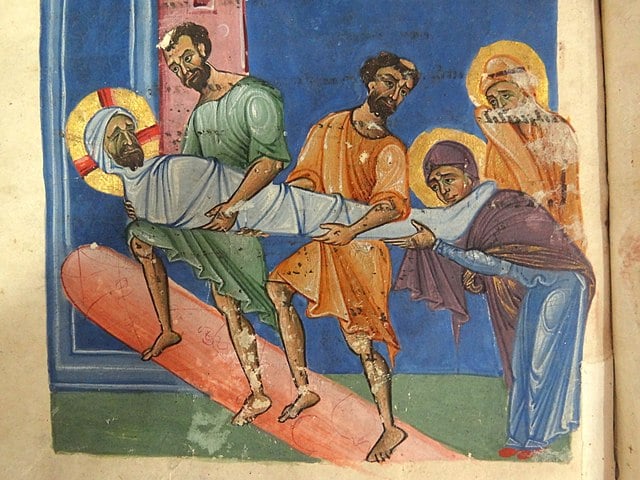

How modern are current Islamic burial practices? Do any of them stem back to the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)? Have Muslim funerals evolved over the centuries and, if so, in what ways?

They certainly stem back to the Prophet, and even earlier than that. I mean, look at the body of Jesus (PBUH). Jesus was wrapped in a shroud. It's the same as we do today. We use the same shroud. So, our burial practices are ancient.

Are there any specific mourning customs in Islam?

A friend of mine is a doctor who worked in a hospital in Saudi Arabia, and he encountered some from Eastern Arabia who would get so dramatic that the hospital staff would have to call security when somebody died. The women would wail and lie on the ground, and they would pull their hair, beat their chests, and do stuff like that—which would stop the work of a hospital. Because they wouldn’t cease when asked to, security would have to drag them off the corridors. On the other hand, some people might lose a 25-year-old child, and (in response to that tragedy) say, “He was God’s gift to us, and God has taken back His gift.” So, you see the two extremes. These reactions to death are cultural; not religious. People in most traditions struggle to distinguish between what is actually part of their religion and what is simply a cultural practice common among people in their religion. Islam does not formally encourage dramatic morning in the way these women from Saudi Arabia mourned.

Formally, if a Muslim woman’s husband passes away, she traditionally mourns the death for four months and ten days. (This is called “Iddah.”) During her Iddah, the widow typically stays home, except if necessity requires otherwise. During this period, she does not wear “fancy” clothing, makeup, or jewelry. The Shariah does not specify any particular color of clothing that should be worn by the bereaved, but it is a time of remembrance.

Placing wreaths or flowers on their grave, or paying homage to the dead, are usually considered inappropriate ways to mourn the passing of a loved one.

How did “Khadeeja Cemetery” get started? And what is its primary purpose?

The Islamic Society of Greater Salt Lake is the oldest and largest Muslim organization in the State of Utah, established in 1984. Adjacent to this Center is Khadeeja Cemetery, established in 2015. It is the only private cemetery for Muslims in the state of Utah.

Everything is mortal; there is only one being who is immortal—our Lord, Allah. Everyone will die in this world; that’s a known reality. However, most of us are not prepared for that reality. The Islamic Society has been providing funeral services for several years and during this time we have experienced many community members who were not aware of the funeral process or had not planned for this inevitable event. So, the Islamic Society was started to help with this process—educationally, emotionally, and even financially. We train Muslims on the process, we prepare the bodies of the deceased, we help to lower the cost of a funeral by doing all things at cost—and using volunteers to drive down costs. Many organizations take advantage of families as this most difficult of times, charging exorbitant prices for basic services needed at the time of death. We seek to do the exact opposite—offering these needed services at minimal cost. Our funerals and cemetery plots costs thousands of dollars less than commercial ones.

I’ve seen a few “Muslim Free Burial Societies.” What can you tell me about that? Does Khadeeja Cemetery do anything like that?

Yeah, we have 15 fully paid graves. The funeral packages are ready to go at all times. And when three or four are used, somebody will anonymously pay for new ones. So, up to 15 people at a time—with zero income or zero capacity to pay a single dollar toward funeral expenses—can be provided for by us.

We don't know where the money comes from. Somehow, we are able to this. God simply provides. I use the Arabic word “Barakat.” It means “blessings.” It is the same experience as how Jesus (PBUH) had a few fish and yet he fed the whole congregation. You understand that concept? We are a very small organization, but somehow we are able to do this without asking for help. So, people have been kind and generous—and we pass that generosity along to those in need.

How has doing this kind of work influenced you spiritually? Is there a sacred side to what you do?

Well, in my professional field (anesthesia), for example, chronic pain is something I don’t like to treat, because you’re dealing with people whose lives are really quite miserable and they are understandably upset about that. With chronic pain, you’re just trying this and that, hoping something will help. With acute pain, however, treating a patient is gratifying. You break an arm, for example. I give you morphine and set the arm and BOOM! Everything is good again. That kind of an experience makes you feel good about being a doctor. The hardest thing for me, however, is pediatric palliative care. If a 70-80-year-old person is dying, you can say, “He had a good life. Look at his posterity. Look at the legacy he leaves.” But what do you tell a mom whose two-year-old has three months to live. How do you console her? I mean, it is beyond words. She might think, “I’ve been a good person. My kid is innocent. I’ve been faithful to my God. I said my prayers. Why has God let this happen to us?” She is on the verge of losing her faith over this trial. There isn’t much I can say to heal that kind of pain. But I can hold her hand and maybe help her through this. It’s a different feeling, and one I can’t put into words. But my work with the deceased and their families has made me more sympathetic, more understanding, more compassionate, and better at communicating. I’ve become a better listener. Medical doctors are trained in the science of death. This work has trained me in the compassion of death—the feeling side of it. Maybe I can just be there for someone and make a difference in their life in that way (when my other training can’t take away the inevitable).

As I understand it, Islamic funerals are often seen as being “for the deceased” rather than for the family and friends of the deceased (as many Christian and Jewish funerals are). Is there still a concern that the Islamic funeral help address the grief and loss of the deceased’s loved ones? If so, how is that grief addressed?

Well, we definitely feel that funerals are for the deceased, more than for the living. The funeral basically offers closure to their life. However, they do accomplish something important for the living. In our tradition, when you die, your window of performing “good deeds” is closed. But those who remain after you can continue your good deeds. First, your death gives them reason to pray—to make supplication for you, and so your life and death provoke spiritual acts in the lives of the living. Second, if you taught others—as a teacher, as a parent, or in any other capacity—those teachings continue; either because people live what you taught them, or they teach others what they were taught by you. So, again, your teachings, your words, live on after you. Finally, if you used your wealth to build something, like a school, a hospital, or something else, the things your wealth built continue on after you and thereby continuing to bless people after you’re gone. Each of those are things the deceased do for the living who remain.

The death of someone close to us is time for self-reflection. There is a story in Islam about the Prophet Jacob (PBUH). The “Angel of Death” comes to him, and Jacob asks, “Couldn’t you have given me a little warning?” To which the Angel respectfully states, “How many funerals have you been to? Weren’t those warning enough?” You know, life is temporary—and every death of someone we’ve known reminds us of that. It reminds us to prioritize what’s most important because, when it is our time to die, it won’t matter how much money you lost in a business deal, or what schools you attended. All that will matter is if you put God first in your life and placed your family as a priority over worldly things.

What’s a common misconception about Islamic funerals—perhaps misunderstandings that non-Muslims have?

I think there's a lot that you might see on TV or the internet which is abnormal and gives false impressions. When people are buried in Gaza (in Palestine), for example, you know how they carry the dead on their shoulders in this fast pace—almost like they’re denying the pain? Or there’s some of the hysterics you might see, which almost take the dignity away. To me, that is very abnormal, and people may look at it and think “That is how a Muslim funeral is.” But this is very different from how most Muslim funerals would be conducted. So, those are common misconceptions that we get from watching a dramatic custom in one location and assuming that it is representative of the entire tradition—which it is not.

What else should people know about Islamic funerals and what your organization does?

It said that death is just a transition. And I think we live in denial about it. That's why we celebrate birthdays, right? If you understood things, then you should be crying on birthdays because you have one less year to live. But, instead, we celebrate them because we are in denial about death.

In so many ways, life is a test. And, at some point, our test is over. Gravity, pain, suffering, loss—all of these things come to an end; and hopefully we did well on the test of mortality. Like sitting for your medical boards (to get your license)—where you walk out of exam as light as a feather because your board exam is done; that’s kind of how death should be for us. But, instead, most people fear it and wish to avoid it. Of course, I have no business telling another person how to “answer” the “questions” on their “test” of life. I can just wish them “good luck” and hope they do well. Our tests are very individualized. But I look at life and death from that perspective, and there are many times that I examine my own life and I feel so blessed, where I think, “God, things can only go worse because my life has been so good. I’ve got my boarding pass in my hand. Whenever it’s time, I’m packed and ready to go.” I look forward to what’s next. I hope I have done good on my “test.” Hopefully I’ve “passed.” Perhaps we just need to do a better job of “selling” death—because we really do fear what we should look forward to as an opportunity to dwell with God.

Interview conducted, transcribed, edited, and condensed by Alonzo L. Gaskill.

11/1/2022 4:05:39 PM