The third is Saint George of Mytilene, hailing from the Greek island of Lesbos. The erotic charge of that hometown calls the ancient Greek poet Sappho to mind, as well as the debates about the meaning of the word "lesbian," then and now. If Sappho was a passionate lover of women, and if she hailed from the island of Lesbos, then perhaps a Lesbian is a woman whose primary erotic attention is devoted to other women. And if a saint hailed from her hometown, well then the Ides of February seem to make it harder to draw a sharp line between pagan and Christian, between homoerotic and heteroerotic forms of passionate romantic love.

How then, given this vast confusion of Greco-Roman and hagiography and martyrs' lists, has this day come to be celebrated as the global holiday for lovers, unmarried and married alike?

Geoffrey Chaucer seems to have been one of the first to write about Saint Valentine's Day as if it were associated with the cult of romantic love. Chaucer, of course, was also the first great poet in the English vernacular, refusing to submit to the cultural domination of ecclesiastical Latin. And with this declaration of independence of the secular tongue, came the semi-secularization of the sacred Christian calendar. To be sure, marriage had always been the most secular of the church's seven sacraments.

Long before Juliet finally confessed it, the lover in the first blush of excitement was always thought to be dangerously distracted and already half a pagan. "You are the god of my idolatry," Juliet gasps. Saint Paul had worried about this a long time earlier in several of his letters, urging those Christians who could not be celibate to get themselves married before real romantic passion entered the picture and threatened to unseat the soul.

These days, of course, and under the lingering pulse of Romanticism, we revel in that very unseating, and are expected to thank our lover for it with all manner of gifts, ranging from chocolates to flowers to dinner to diamonds.

How have we gone from a beheaded priest to a giddy worldwide day of romantic love? In a word: the widespread conviction that love is a dizzying sacrifice.

If we ponder the primary Valentine's Day symbol, a human heart pierced by an arrow, then the connection may be easier to see. Jesus himself had famously warned that if you wish to find your life you'll need to lose it first. Many a Romantic artist has said the same: the self must clear out for the spirit of creativity to enter. Loss of self is perceived as fulfillment of self.

Now enter the lover in love, long venerated by poets and rhapsodes of all stripes, starting with the lyrical Lesbian, Sappho herself. The lover who tries to leave reason in control, she warns, does not follow her god to the end. It is the very chaos of love, the swirl of love, that may link our modern Romantic musings to the Greeks—mediated to us, ironically enough, by the martyr-rolls of the early churches.

There is also a Roman residue to this eminently modern holiday, the Roman festival of the Lupercalia, held on the Ides of February (February 13-15). Recall Shakespeare once again: it was during the Lupercalia, he imagined, that Julius Caesar was offered an emperor's crown and refused it three times. Just one month later, during the Ides of March, he lost his life in a bloody hail of daggers. Loving is linked to dying.

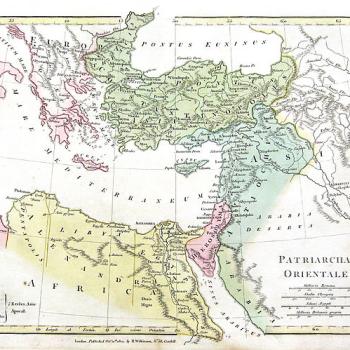

While we know little about it, the Lupercalia seems to have been a curious Latin festival with mysterious Greek origins. Later Roman writers like Plutarch suggested that it originated in Arcadia in southern Greece, where Lykaian Pan was worshiped (lykos is the Greek word for wolf). The Roman poet Virgil would turn that same Arcadia into an ideal image of Paradise, a lost Golden Age of musical shepherds and right religion, in a marvelous cycle of poems called "The Eclogues" (or "The Bucolics"). Some later Christians felt that Virgil had predicted the birth of Christ in one of them; more likely it was a reference to the birth of Octavian, later Caesar Augustus.

In any case, this mysterious rural Greek festival took a more elaborate form in the city of Rome. The Greek god Lykaian Pan becomes Lupercus (lupos being the Latin term for wolf). A cave below the Palatine Hill was identified as the very spot where the twins, Romulus and Remus, were nursed by the she-wolf of Rome, one of the most famous of Rome's founding myths and images. In mid-February, several patrician priests called "Luperci" would go to the Lupercal Cave and bring the half-naked statue of Lupercus into public view. They would sacrifice two goats and one dog, while the Vestal Virgins offered vegetarian cakes.

After a feast the Luperci would run around the Palatine, dressed in the fresh skins and flagellating the crowds with the sacrificial sinews. Such a beating was believed to promote fertility in the women of Rome. This is all according to the report of an early Christian philosopher, Justin the Martyr, no great lover of pagan culture or pagan holidays.