By Salma Hasan Ali

Central Asia Institute

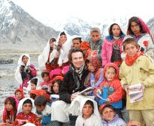

Greg Mortenson (kneeling) stands with the first children to get to go to school in the Pamir mountains of northeast Afghanistan.

Greg Mortenson (kneeling) stands with the first children to get to go to school in the Pamir mountains of northeast Afghanistan.

Washington - President Barack Obama's recently announced counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan and Pakistan is likely to precede a more aggressive campaign in northwest Pakistan, as illustrated by the decision to send thousands more troops to the "AFPAK" region by the end of the year.

On a different level of U.S.-South Asian engagement, American Greg Mortenson recently received Pakistan's highest civilian honor, the Sitara-e-Pakistan (Star of Pakistan), for efforts in promoting peace in the region. Mortenson's approach doesn't involve counterterrorism operations or robust troop numbers.

His "weapon" for promoting peace? Educating girls. His modus operandi: drinking lots of tea.

I recently had the opportunity to travel to Pakistan to see him in action. Mortenson is the founder of the nonprofit Central Asia Institute, which has built nearly 80 schools in the most remote areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan and provides education to more than 33,000 children, including 18,000 girls.

For more than a decade, Mortenson has had tea with the Taliban, religious clerics, tribal chiefs, village elders, heads of government, militia leaders, conservative fathers, intimidated teachers and nervous children, which inspired the title of his best-selling book, "Three Cups of Tea."

"The first cup, you're a stranger; the second cup you become a friend; the third cup, you're family," says Mortenson.

Mortenson has spent more than 70 months in Pakistan and Afghanistan, walking for miles on treacherous roads and sitting in the dirt for hours talking to villagers.

"Whoever he sits with, he gives them so much respect," says Mohammed Nazir, one of Mortenson's Pakistani colleagues at CAI. "People want to be with him, have tea with him."

Language doesn't seem to be a barrier. He speaks some Urdu, Balti and Farsi but, in the end, Mortenson does more listening than talking.

In each village, Mortenson asks the mothers how he can help them. "Greg always asks, ‘What can I do for you?' " says Saidullah Baig, another team member. They all respond, "We want our children to go to school."

His story is where the real lessons lie for winning "hearts and minds" in the region. And while this process can take several years, Mortenson is in no hurry.

In one village, it took eight years to persuade the local council to allow a single girl to attend school. By the time the school opened in 2007, there were 74 girls enrolled. One year later, the number had tripled.

He involves each person in the community. They contribute labor, land, cement or meals to help build the schools. In his model, there is transparency in how funds are used. Every family is assigned a role, and the entire community becomes invested.

No wonder only one CAI school has been attacked by the Taliban. Even then, the local militia leader fought back and the school was reopened two days later.

U.S. foreign policy and military leaders have something to learn from the results Mortenson has achieved. Long-term success in the region takes patience, resilience and the ability to listen.

It takes understanding people's culture and faith and involving them in shaping their own futures. This approach is the best defense against the advancement of extremism.

Ultimately, it takes building relationships - perhaps one cup of tea at a time. President Obama would do well to consider a new surge strategy by sending thousands more tea drinkers to the AFPAK region.

• This article was written for Common Ground News Service, which promotes better Muslim-Western relations.

• Salma Hasan Ali is a writer specializing in South Asia.

1/1/2000 5:00:00 AM