By Maria Tattu Bowen

For my first communion in 1967, I received what would soon become my favorite childhood book, a book clamoring more loudly for my attention than even Black Beauty or The Nancy Drew Mysteries. The Picture Book of Saints featured full-color pictures that drew me to them over and over again. Tracing with my fingers the outlines of St. Tarcisius' golden cloak as he used it to shield the Eucharist, or the vision of Our Lady as she appeared to St. Bernadette of Lourdes, I would read their stories and wish that some day I would be as brave and holy as they were.

For my first communion in 1967, I received what would soon become my favorite childhood book, a book clamoring more loudly for my attention than even Black Beauty or The Nancy Drew Mysteries. The Picture Book of Saints featured full-color pictures that drew me to them over and over again. Tracing with my fingers the outlines of St. Tarcisius' golden cloak as he used it to shield the Eucharist, or the vision of Our Lady as she appeared to St. Bernadette of Lourdes, I would read their stories and wish that some day I would be as brave and holy as they were.

Even before The Picture Book of Saints, however, St. Lawrence, namesake of my grammar school, epitomized for me the astonishing collision of courage and faith found in the lives of many saints. As we entered first grade, the nuns fascinated us by telling his story, a story whose facts remain in doubt when examined closely but one that cannot fail to impress. A church deacon roasted to death on a gridiron by minions of the emperor Valerian in 258, St. Lawrence said calmly to his murderers as they burned him alive for his faith, "Turn me over, I'm done on this side."

The stories of saints, interwoven with the stories of the Bible and with our own stories, form the rich fabric of our church whose very food, the Eucharist, rests on recounting to the gathered community the central story of our faith. Unlike almost anything else, stories quicken our senses, enliven our imagination, and help us live into the Reign of God. With this in mind, let us revisit some of the saints over the next several months, wrapping our minds around their stories, opening our hearts, and seeing what they hold for us in the present moment. We begin with St. Mary Magdalene.

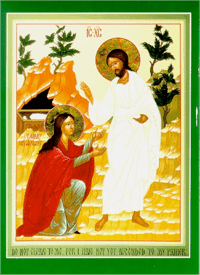

The Picture Book of Saints depicts Mary Magdalene seated on a straw mat in what appears to be a cave, gazing at a cross fashioned of twigs. Her bare feet rest on gravel, tattered clothes drape her body, and golden-red hair frames her beautiful face, spilling down her back. A human skull sits next to Mary's thigh, and a halo glows around her head. The picture of asceticism, Mary, as depicted by this book's authors, is living a life of penance for her sins.

However, there is something wrong with this picture and with the text in the book that accompanies it. In the 6th century, Pope Gregory I gave a homily that linked Mary of Magdala with the sinner woman of the Gospels who washed Jesus' feet with her tears and dried them with her hair, and with Mary of Bethany, Martha and Lazarus's sister who, in John's Gospel, anointed Jesus' feet with costly scented oil. This homily has reverberated through history, influencing iconography and believers; however, a close reading of the Bible suggests that the un-named sinner woman, Mary of Magdala, and Mary of Bethany are three distinct characters.

Indeed, unlike other women, Mary of Magdala is often referred to by scholars as Jesus' female disciple, so close to him that she stood weeping with his mother at his crucifixion and so beloved by him that he appeared to her first when he rose from the dead. Luke reports that seven devils were cast out from Mary Magdalene and that along with other women she followed Jesus from Galilee to minister to his needs. Like the other Marys, she desired to anoint him, but Mary Magdalene did not have the opportunity, for she ventured to his tomb with her spices only to find it empty.

Later, Gregory of Tours tells us that Mary moved to Ephesus. However, a vibrant cult of Mary Magdalene later developed in France, where she was said to have arrived with Lazarus. Tradition holds that she converted all of Provence, and the Benedictine Abbey at Vezelay features her relics as does the Dominican church at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume. Further, apocryphal gospels, like the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, shed light on her story, even as they raise further questions about her.

The moral of these three stories is not only that these three women loved Jesus but that Jesus loved women, loved them so much in fact that he let them touch him and kiss him and pour oil on him, so much that he appeared as the risen Christ to women before he did to those we call his disciples.

Pondering this story raises questions worth considering in prayer:

1. What became of the nameless woman whose love for Jesus so overcame her she fell down crying before him, washing his feet with her tears, kissing them again and again, drying them with her hair? Under what circumstances might I make -- or have I made -- such a public demonstration of my repentance and love?

2. Marveling at Mary of Bethany's sensuous, extravagant anointing of Jesus, I wonder how I might demonstrate such generosity in my love of God, invoking the senses as I worship?