In Part One we explored the mandala as sacred circle and its appearance as rose window, labyrinths, and rosaries. Mandalas also appear in the visions of some of the great Christian mystics.

In Part One we explored the mandala as sacred circle and its appearance as rose window, labyrinths, and rosaries. Mandalas also appear in the visions of some of the great Christian mystics.

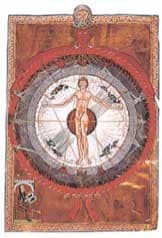

The 12th-century German Benedictine Abbess, Hildegard of Bingen, began experiencing visions at the age of five and at forty-two heard God's voice commanding her to write them down. She wrote three books of visions in all, which were also illuminated with rich corresponding images, and so we are left with visual keys to the way God was revealed to her. These visions were essentially instructions on how to achieve salvation and were very rooted in the apocalyptic worldview of her time. Several of her visions appear in mandala form including an image of the Trinity, the choirs of angels, and the human person in relationship to nature. In other illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, the universe is often depicted as a series of concentric rings pointing to the sense of wholeness nature evoked in medieval hearts.

The 16th-century Spanish Carmelite mystic Teresa of Avila's most well-known work is the Interior Castle. This text is the description of the soul's journey of faith toward deeper intimacy with God. She compares the soul to a castle with seven successive interior rooms or dwelling places. A person enters the castle through prayer and meditation and the journey through each successive room is marked by different stages of maturity in the spiritual life. The castle is in the shape of "a most beautiful crystal globe" and in the seventh and innermost chamber is the dwelling place of God, radiant and luminous. The closer one gets to the center, she writes, the more intense the light becomes.

Teresa's vision has offered much wisdom for the spiritual journey over the centuries, and is the mandala shape as a template for her image of God's dwelling place at the very center of our own being. A person moves through the first three rooms by deepened commitment to and the practice of prayer, and as she or he moves more deeply inward, God becomes the magnet, luring the soul closer to the center. Within us dwells a sacred circle, at the heart of which beats God's presence.

The liturgical cycle of the church year can also be viewed as a mandala, circling back again and again to the foundational themes of our faith and belief. In a three-year cycle we return to the sacred stories that shape us over and over again. We believe that our sacred texts, while unchanging, speak to us in new ways at each new moment in time. The repeating rhythm and movement through the great stories of scripture and the narrative of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection offer us a model for the great cycles of our own lives and the invitation we encounter to embrace death and new life.

The liturgical cycle of the church year can also be viewed as a mandala, circling back again and again to the foundational themes of our faith and belief. In a three-year cycle we return to the sacred stories that shape us over and over again. We believe that our sacred texts, while unchanging, speak to us in new ways at each new moment in time. The repeating rhythm and movement through the great stories of scripture and the narrative of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection offer us a model for the great cycles of our own lives and the invitation we encounter to embrace death and new life.

The circle is without beginning and end and symbolizes the eternal nature of the divine. The mandala invites us to discover our own hidden wholeness and embrace a God who lives both at the center and at the edges of life.