Midway through the 45-day span of the Iliad, the 8th-century B.C. epic poem about the Trojan War, Homer describes the funeral games for Patroclus, the fallen comrade of the hero Achilles. Achilles, broken with grief, sets out prizes for those who will compete for glory -- a pause in the midst of the war for the sake of sport.

Midway through the 45-day span of the Iliad, the 8th-century B.C. epic poem about the Trojan War, Homer describes the funeral games for Patroclus, the fallen comrade of the hero Achilles. Achilles, broken with grief, sets out prizes for those who will compete for glory -- a pause in the midst of the war for the sake of sport.

Elsewhere, in his Odyssey, Homer returns to the theme of sporting games by describing his hero Odysseus competing against much younger men -- an ancient Bret Favre, if you will -- as a way of showing the hero's towering stature, even amidst the vagaries of his ten-year voyage home from the ten-year war. Some six centuries later, the Roman poet Virgil, returning to the scene of the Trojan War in his Aeneid, describes games in honor of Aeneas' father Anchises: there are rowing races, footraces, javelin contests, and boxing. These games, like those described in the Iliad, represent a peculiar detour amidst a larger divinely-inspired mission.

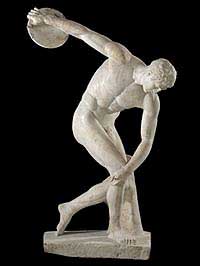

Why do these epics, these towering stories of great men accomplishing great things, grind to a halt in order to describe sporting contests? The short answer, I think, is because sport was for these authors, and those whose stories they told, a microcosm of life. Certainly in the Greek world -- and by extension, the Roman world, which took so many of its cues from its predecessors -- physical prowess was integral to manhood. The painting and sculpture from at least the late 6th century B.C. idealized the athletic male body, perhaps because of the need to promote the skills for warfare. Coupled with the head of an older, wiser man, these sculptures, such as the statue of Zeus or Poseidon throwing a spear, effectively show the ideal of manhood, designed to inspire young soldiers to strive for glory.

Yet these ancient depictions of sport are more than martial propaganda. Saint Paul, writing only a few decades after Virgil, used athletics as a metaphor for the discipline of the good life:

Do you not know that in a race all the runners compete, but only one receives the prize? So run that you may obtain it. Every athlete exercises self-control in all things. They do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable. Well, I do not run aimlessly, I do not box as one beating the air; but I pommel my body and subdue it, lest after preaching to others I myself should be disqualified. (1 Corinthians 9:24-27)

For Paul, as for Virgil and Homer, sport was the most apt metaphor for life itself. In sport, one must practice discipline for the sake of a higher, more distant good. The wreath that Paul mentions is a clear reference to the laurel branches given to the victors of Greek games; Paul suggests, of course, that he is pursuing an even more noble goal in the Christian life: "I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus" (Philippians 3:14).

Sport is life because athletes inspire us to strive to imagine ourselves anew, to reach for goals, to use the gifts of our bodies in marvelous and exciting ways. The discipline of sport reminds us that pleasure is temporary, that suffering can yield greater glory, that our opponents can be friends, that even at our best we are radically dependent on others, that our limits can be surpassed and sometimes obliterated, that our minds can overcome what seem to be insurmountable hurdles.

For the cynic who criticizes the narcissism of athletes or the ugly tendencies of cheating, we must observe that sport is not exempt from the darker side of all human striving: in the Catholic tradition we call this tendency original sin. But we must go a step further, and recognize that our better selves create rules, establish officiating, and hope against hope that our games will elicit the best of all who compete. There is gain, and there is loss: in the old broadcasts of Wide World of Sports, Jim McKay waxed poetic about "the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat." In sports, these are real, and they teach us lessons.

Sport is life because in sport we undertake a kind of spiritual discipline: a way of imagining ourselves in the world, of taking stock of the kinds of human beings we are created to be in relation to others. Athletes don't just speak about what they can do: they speak about who they are. "I'm a runner." "I'm a boxer." "I'm a rower." These disciplines shape self-perception; they build confidence; they affect relationships.