But such mutual enrichment requires time and the willingness really to listen to the other. Instead of highlighting differences, you need to find out what the belief really means to a person and how it affects the way they live. It is easy, for example, to say that Muslims reject belief in the Atonement, but they ask

"Why couldn't God just forgive without a blood sacrifice?" They hold that God did forgive Adam and Eve for their sin.

For some years I was a member of a group of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholars convened by the former Bishop of Oxford. It was moving to discover the deep reverence that some Muslims and some Jews have for Jesus. In the same way, some Christian theologians now recognise Muhammad as a Prophet -- on a par with Isaiah or Jeremiah -- but not as the final Prophet.

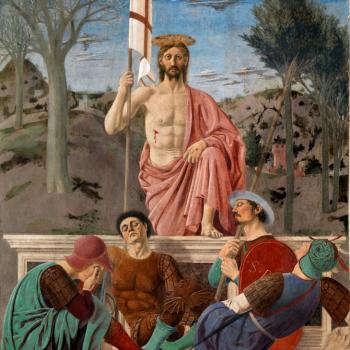

Again I have learned much from Jews, especially in the shadow of the Holocaust, in discussing the complex dimensions of forgiveness and the mystery of suffering -- "Why does God allow hideous acts of genocide?" I now find the picture of a Suffering God more helpful than talk of the ‘King of Kings and Lord of Lords.'

Thirdly, the deepest meeting point is as ‘in the cave of the heart' as we share our spiritual life.

Last year there was a memorable meeting at Black Friars in Oxford, where two monks explained their practice of contemplation or learning to be silent in God's presence, and in response the Dalai Lama talked about his practice as a Buddhist. Buddhists do not speak of a personal God, yet it became clear that in both traditions, the practice of contemplation frees us from self-centredness and deepens our compassion for all living beings. Last year also I took some of the students at the Muslim College in London, whom I teach about Christianity, to Evensong in Westminster Abbey. One of them said afterward that it was one of the most inspiring experiences of his life.

A few years ago I shared with some Sikhs in a pilgrimage to their holy places, including the beautiful Golden Temple at Amritsar. Whenever we entered a Gurdwara, we were expected to bow our head to the ground in respect for the scriptures. It made me aware how casual I have often been in my treatment of the Bible, whereas one should treasure it at least as much as love letters.

Our spiritual life can be enriched by learning about and perhaps sharing in the devotions of others. Karen Armstrong has written that, "far from being a mere exercise in damage limitation, interfaith dialogue can become a spirituality that leads us directly into the divine presence."

Rev. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke is a retired Anglican parish priest, living near Oxford, England. He has been involved in interfaith work for over forty years. He is the President of the World Congress of Faiths and is a co-founder of the Three Faiths Forum. In September 2004 he was awarded a Lambeth Doctorate of Divinity by the Archbishop of Canterbury ‘in recognition of his contribution to the development of inter-religious co-operation and understanding throughout the world.' Rev. Braybrooke is author many books on interfaith work. Marcus is married to Mary, who is a social worker and a magistrate. They have a son and a daughter and six granddaughters.