By Ryan Dinkgrave

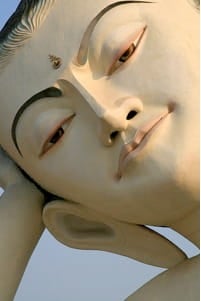

In his article "The Supernatural in Thai Life," John Hoskin says that "a belief in spirits and ghosts has been common to virtually every people in every historical period," and Theravada Buddhism is no exception, offering a number of examples of "unorthodox" practices and rituals that serve a variety of purposes. The first purpose is that people may appeal to a spirit or icon for good health, fortune, or protection for themselves, those they care about, or the village or city as a whole. Secondly, people may present an icon, spirit, or important object with propitiations and offerings as a form of general worship, and to find comfort in the pleasing of the spirit. A third purpose is that people may look to the spirit or icon for advice or precautions before making major decisions or alterations regarding the village and its people. Regardless of the purpose of one's interactions with such spirits, there is always a great deal of respect and admiration involved, such a respect that anthropologist B.J. Terwiel says it "borders on trepidation." Supernatural rituals and practices that are not part of traditional ("orthodox") teachings often exist alongside Theravada Buddhism and serve several purposes for the community and those who participate in these practices.

In his article "The Supernatural in Thai Life," John Hoskin says that "a belief in spirits and ghosts has been common to virtually every people in every historical period," and Theravada Buddhism is no exception, offering a number of examples of "unorthodox" practices and rituals that serve a variety of purposes. The first purpose is that people may appeal to a spirit or icon for good health, fortune, or protection for themselves, those they care about, or the village or city as a whole. Secondly, people may present an icon, spirit, or important object with propitiations and offerings as a form of general worship, and to find comfort in the pleasing of the spirit. A third purpose is that people may look to the spirit or icon for advice or precautions before making major decisions or alterations regarding the village and its people. Regardless of the purpose of one's interactions with such spirits, there is always a great deal of respect and admiration involved, such a respect that anthropologist B.J. Terwiel says it "borders on trepidation." Supernatural rituals and practices that are not part of traditional ("orthodox") teachings often exist alongside Theravada Buddhism and serve several purposes for the community and those who participate in these practices.

The first major purpose of "unorthodox" rituals and practices in Theravada Buddhism is to appeal to a spirit or icon for protection or goodwill, such as good fortune, health, and luck, for themselves or others. Whether one is in a village or a city, and whether the guardian spirit presides over a small house or a large city, people will pray at the shrine to it to request the spirit's assistance or will to bring them good fortune and health. In Burma, nats, defined by Yves Rodrigue in "The Cult of the Nats" as "spirits who have adopted human shapes, easily identified by their individual features, their mounts, their clothes and the rituals at their festivals" are seen as fierce protectors of a place, and failure to pay "necessary respect due to them" results in their dislike and lack of compassion for the disrespectful party.

Rodrigue lists many occasions upon which offerings are made to the nat for protection or goodwill, such as the construction of new buildings, the opening of a celebration, a major career move, and the traveling of a road or river. While one not aware of the importance of these practices may write the threat of the nat's lack of compassion for those who fail to show respect off as an idle threat, it is taken very seriously in such cultures. According to Hoskin, "the sickness or misfortune that befalls a household, for instance, could be attributed to the guardian spirit becoming in some way displeased." Hoskin continues to stress that there are other spirits beyond those that are appeased to achieve good, such as phi lawk that haunt and pester people, and certain spirits that inhabit the heavens and hells.

The second major purpose of rituals and practices not detailed in traditional teachings that exist alongside Theravada Buddhism is the comfort people seek by making propitiations and offerings to please a spirit. Hoskin says "offerings of flowers and food are regularly made at shrines in order to appease the guardians," and Rodrigue says that in the case of the nats in Burmese daily life, "offerings at every occasion, at any moment, are constantly being made to them." Almost every Burmese home is adorned with a nat-sin, a cage that houses the guardian nat outside the home, and many contain a special room in which a shrine or mount for the resident nats exists. Rodrigue explains that people always make certain to pay respect to the nats before "performing their devotions to Buddha," further emphasizing the important ties between these supernatural and ritualistic practices and the teachings and practice of Theravada Buddhism. He defines nats not as heroes, saints, martyrs, ghosts, nor any other predefined concept of nonhuman beings, instead recognizing them only as an unofficial (and yet very important) attribute of some practices of Buddhism, coexisting with the ancient and established traditions.

The third major purpose of such supernatural rituals and practices that coexist with Theravada Buddhism is that people may look to the spirit or icon for advice or guidance before making major decisions or alterations. For example, Hoskin relates a story from the Bangkok Post in 1991, which told of how Thailand's Army Commander-in-Chief of the time visited the City Shrine in the town of Nakhon Si in southern Thailand. As Hoskin tells it, "quoting ‘well-informed sources,' the newspaper article related that during the ceremony, the spirit of the guardian of the City Shrine had advised the army chief through a medium not to resist the popular demand for a democratic constitution ‘otherwise he might encounter a fateful event.'" While the facts of the story may be difficult to prove, such is the nature of all supernatural practices and rituals, only evident by their existence and practice, with unverifiable results. On a smaller scale, one may ask the spirit or nat for guidance regarding their personal lives, or for help in solving interpersonal conflicts and disputes. Regardless of what they seek, the belief in the spiritual power of the icon or being testifies to the respect and importance of its coexistence with Buddhist practices.