By Shai Ginsburg

During the 1980s, Israeli filmmakers were preoccupied with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the 1990s, they explored the dynamic between Israel's urban centers and the country's periphery. The past decade has witnessed a rise in films that seek to portray the experience of communities previously considered marginal to Israeli cinema. Avi Nesher's latest drama, The Secrets (Israel/France, 2007), joins a host of recent Israeli films, both feature-length and documentary, which explore Israel's ultra-orthodox community.

During the 1980s, Israeli filmmakers were preoccupied with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the 1990s, they explored the dynamic between Israel's urban centers and the country's periphery. The past decade has witnessed a rise in films that seek to portray the experience of communities previously considered marginal to Israeli cinema. Avi Nesher's latest drama, The Secrets (Israel/France, 2007), joins a host of recent Israeli films, both feature-length and documentary, which explore Israel's ultra-orthodox community.

Ultra-orthodox Jews were mostly absent from Israeli filmmaking until the 1990s. This is no surprise, because Israeli cinema has historically reflected the identity of the Israeli establishment, promoting secularism and criticizing religion as a sign of ethno-nationalism rather than as a cultural facet of everyday life. From the late 1990s, however, the religious experience moved to the center stage of Israeli cinema.

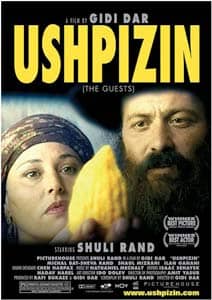

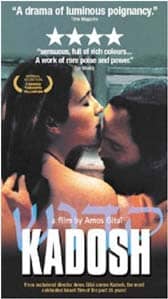

Inaugurating the new wave of religious films was Yossi Somer's 1998 film The Dybbuk of the Holy Apple Field Amos. Somer's film was followed by such films as Gitai's 1999 Kadosh, Sandy Simcha Dubowski's Trembling Before G-d (2001), Anat Zuria's Purity (2002) and Sentenced to Marriage (2004), Ilil Alexander's Keep Not Silent (2004), Giddi Dar's Ushpizin (2004) and, most recently, David Volach's My Father My Lord (2006), Raphael Nadjari's Tehilim (2007), and Avraham Kushnir's Bruriah, which premiered a couple of weeks ago at the Jerusalem Film Festival.

Different as "orthodox films" are from each other, they all focus on the struggle of their characters to reconcile their daily, personal experience with the firm halakhic framework within which they choose, or are forced, to lead their lives. These productions radically diverge, however, in the way that they portray the friction between everyday life and Jewish law.

Different as "orthodox films" are from each other, they all focus on the struggle of their characters to reconcile their daily, personal experience with the firm halakhic framework within which they choose, or are forced, to lead their lives. These productions radically diverge, however, in the way that they portray the friction between everyday life and Jewish law.

Some of the films -- harsh as their critique of halakha may, at times, seem -- also portray the complex strategies employed by believers in their attempts to reconcile their knowledge of the world with the tenets of tradition. Others, most notoriously Amos Gitai's Kadosh, portray the ultra-orthodox community from the perspective of a presumably "enlightened" and "liberated" secular world. From this point of view, a binary opposition is set up between religious narrow-mindedness and secular liberalism. Halakhic existence, as the form of Jewish religious life, is perceived to be oppressive. The only possibility for individuals to be true to themselves and realize their aspirations is by shedding the oppressive yoke of faith.

Two themes consistently reappear in orthodox films, namely, sexuality and the experience of women. This is no surprise, for the two, of course, are tightly linked in halakha. The Babylonian Talmud thus states: "R. Isaac said: A handbreadth [exposed] in a [married] woman constitutes sexual incitement... R. Hisda said: A woman's leg is a sexual incitement ... R. Samuel said: A woman's voice is a sexual incitement ... R. Shesheth said: A woman's hair is a sexual incitement." The Hebrew is blunter, and employs the term erva, the pubic hair, for "sexual incitement." Such statements provide ample ground for critics not only to explore the framework of halakha, but also to outright defy it by presenting that which is forbidden: women's flesh and voice.

Two themes consistently reappear in orthodox films, namely, sexuality and the experience of women. This is no surprise, for the two, of course, are tightly linked in halakha. The Babylonian Talmud thus states: "R. Isaac said: A handbreadth [exposed] in a [married] woman constitutes sexual incitement... R. Hisda said: A woman's leg is a sexual incitement ... R. Samuel said: A woman's voice is a sexual incitement ... R. Shesheth said: A woman's hair is a sexual incitement." The Hebrew is blunter, and employs the term erva, the pubic hair, for "sexual incitement." Such statements provide ample ground for critics not only to explore the framework of halakha, but also to outright defy it by presenting that which is forbidden: women's flesh and voice.

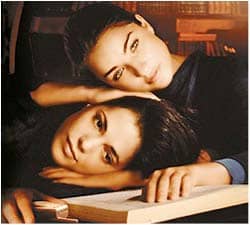

In The Secrets, Avi Nesher follows this route, making the film's centerpiece an ultra-orthodox woman, in voice and in flesh. The Secrets is the story of Naomi, played by Ania Bukstein, the brilliant, intellectual daughter of a prominent Bnei Brak Rabbi, portrayed by Israeli entertainer Sefi Rivlin. Following her mother's death, in order to postpone her arranged marriage to one of her father's students, Naomi convinces her dad to allow her to attend a Jewish seminary for women in the ancient Kabalistic town of Sefad. Such a request is highly unusual in the ultra-orthodox community, where higher studies are still very much perceived to be the domain of men, while marriage and family is the assigned realm for women. At the seminary, Naomi encounters the free-spirited Michal, played by Michal Shtamler. Michal was sent there by her father after she had been expelled from her previous seminary, in the hope that in Sefad she would be matched to a suitable man.