Leviticus 25:1 - 26:2, 26:3 - 27:34

By Talia Davis

The parshot (weekly Torah portion) for the week ending May 8 is Behar and Bechukotai. Behar means "on the mount" in Hebrew and is the fifth word (and first distinctive word) in the portion. Bechukotai means "by my decree" in Hebrew and is the second word (and first distinctive word) in that portion. Be sure to check out the cartoons at the end for some great perspectives on these Torah portions.

The parshot (weekly Torah portion) for the week ending May 8 is Behar and Bechukotai. Behar means "on the mount" in Hebrew and is the fifth word (and first distinctive word) in the portion. Bechukotai means "by my decree" in Hebrew and is the second word (and first distinctive word) in that portion. Be sure to check out the cartoons at the end for some great perspectives on these Torah portions.

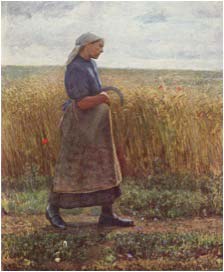

To start, Behar talks about the year of shmita. Shmita happens once every seven years and requires Jews to take a year off from farming, which lets the land rest and in turn enhances the soil. This year of sabbatical still happens today. In fact, just a year or two ago was the shmita year. Farmers suffered because they couldn't sell crops and Jews found it difficult to purchase food (we weren't allowed to buy from Israel since the land should be resting). This time of the cycle reminds us that the land is G-d's and not ours. The parsha tells us we can have six years of farming and thinking that we are the masters of the land and then in the seventh year, we and the land must rest. We can't reap, we can't sow; we are on a forced sabbatical too, which is a good time for our busy selves to reconnect with Hashem. Like it says in a phrase I enjoy -- "Let go, let G-d."

After seven sabbatical cycles, we celebrate a 50th year jubilee. This is when all indentured servants are set free and all borrowed or sold land goes back to the original owner, again reminding us that we don't own land or people; all that is, is G-d's.

The next portion is Bechukotai. This one gets hefty with talk of reward and punishment. G-d tells Moshe what's up. It's a frank conversation, like a parent talking to a child. If you are home by curfew and do your chores, I will provide for you what you want and need. But, if you don't listen to me, there will be consequences. It's a simple equation: keep covenant that we committed to by becoming the tested or chosen people = get rewarded. Don't do what we committed to = punishment.

The next portion is Bechukotai. This one gets hefty with talk of reward and punishment. G-d tells Moshe what's up. It's a frank conversation, like a parent talking to a child. If you are home by curfew and do your chores, I will provide for you what you want and need. But, if you don't listen to me, there will be consequences. It's a simple equation: keep covenant that we committed to by becoming the tested or chosen people = get rewarded. Don't do what we committed to = punishment.

The punishments, which we will get to in a minute, seem monstrous. In comparison, the rewards come across to us today as simple. Rain in its season, plentiful crops, victory over enemies, and peace. Some people think, "If we fight well, we will be victorious over our enemies." Or, "We can't control the weather but if I fertilize and work the soil well, my crops will be large and plentiful." Other people believe that these are functions solely of G-d.

Despite what you believe, if you follow the precepts laid out, you will find success. Why? Well, if you follow G-d's commandments, you will be treating people nicely, so there will be peace. You will let your land lie fallow at least once every seven years so your soil won't be depleted of minerals and essential nutrients. You will be respectful to all and that will help in dealing with enemies; it may even eliminate them if everyone follows these rules. So maybe you don't believe that G-d affects the weather or your crops or people's attitudes, but following these rules certainly will change things.

Now, let's talk about breaking the covenant. G-d (or Torah) gets pretty fierce here. Basically it says that if you don't do what G-d says, you will have a string of problems. What does that mean? Does it mean if you don't follow the Torah exactly, then you will be punished? Some groups believe that, because that is how they interpret it. The general attitude behind this is that if you don't believe what I believe, then this is how G-d will punish you.

This tack has been used (in my opinion, to a horrific degree) by several extremist groups --most notably by a specific Christian extremist group that I refuse to name (and thereby give free publicity to their hate campaign against Jews, Catholics, and homosexuals). This group's members continuously quote Leviticus 26:29, which says that one consequence of disobedience is that people will eat their own children.

What?! How can this be? Our loving and kind G-d, now giving us an ultimatum of do what I say or eat your young?! That doesn't feel like my G-d. Personally, I was appalled. I had to research further. I mean, this is in direct conflict to earlier Torah passages where it says that a child should not be punished for the sins of its parents. I read different Jewish versions, and I looked for Rashi's commentary (a famous and reliable commentary). Even Rashi won't touch this one, or at least I couldn't find it. But my father and I sat down and talked it out.

What?! How can this be? Our loving and kind G-d, now giving us an ultimatum of do what I say or eat your young?! That doesn't feel like my G-d. Personally, I was appalled. I had to research further. I mean, this is in direct conflict to earlier Torah passages where it says that a child should not be punished for the sins of its parents. I read different Jewish versions, and I looked for Rashi's commentary (a famous and reliable commentary). Even Rashi won't touch this one, or at least I couldn't find it. But my father and I sat down and talked it out.