So what kinds of teachings and practices are necessary to seed this missional imagination in young people? What is necessary for us to move beyond a faith that is based on beliefs to a way of being in the world?

I'm persuaded that you have to tell your story. The story that defines the community is not incidental. Telling your story is a little different than adhering to a certain set of doctrines.

Part of why I'm persuaded that telling the story is a good idea, is that because it's been largely homogenized into the gospel of niceness. And that's an understandable homogenization; there is a seed of that you can trace back to the Gospel, because the Gospel does want us to treat people well! But it's been drained of all the passion that gives rise to that, and by passion I mean loving something enough to suffer for it. That's the way God love us, and that's how God calls us to love others and to love God in return. That, in a nutshell, is what the Christian story is about.

I also want to help parents understand the distinction between passing on beliefs versus passing on what you love. That's a fundamental misunderstanding that many parents (and adults) have. They say, "I don't know enough to talk to youth." But sharing your faith is not about sharing what you know! It's sharing what -- and who -- you love that is compelling to kids. What you know or don't know is kind of second order.

I found that very compelling, and the implicit call then, to us as adults, to ask ourselves, "What do we love? What do we find compelling about this faith we say we believe in?" I actually see this as an exciting opportunity for all of us to re-engage our faith journey and rediscover a vocabulary of faith. You mention in your book that one of the characteristics of the most highly devoted youth in the NYSR study was that they were from families where religious language was an organic part of family life (the Mormon Church and the black church are two examples you cite). For those of us who aren't so confident in our own faith vocabulary, what would you recommend?

The most obvious way to learn a language is to hang around somebody who speaks it. There are people in our congregations who speak a faith language. So we need to identify who they are and hang out with them! I'm thinking of a couple in a church my husband and I attended when we lived in Pennsylvania who were at least 25 years older than us, and they'd die if they knew we thought of them as spiritual directors -- they don't' even know what that term means -- but in fact they functioned that way for our family. And part of the reason was that they had a very explicit language of prayer. They spoke about prayer as though it were just a normal part of their lives, because for them, it was! By spending time with Bud and Norma, we learned to talk about our lives in those terms too, because they created this framework in which that was possible. As Peter Berger says, talking about something makes it real to us. My own background is in conferences and camping ministries. Christian camps would be one example of a microcosm where teenagers can practice this language of faith.

Do you think our uneasiness with religious language stems from living in a multi-religious country and world, where we are trying to be conscious of not offending the other, as well as our reluctance as mainline Christians to be associated with the Religious Right?

That's one of the most recent versions of it, but I think there's been ambivalence about religious language for a long time, even before we realized how multicultural we are. I think it can be traced back to the medieval university, when theology first sought credibility in a university system. That required a different kind of language than the language of piety that had been what the church offered. And so these two streams of theological discourse developed throughout the Enlightenment: the official church language, which was trying to be conversant with the sciences, and then there was the language of piety and mystery and power, found in the hymns, the liturgy, the prayers -- stuff that doesn't make any sense to people outside the church, but for those on the inside, this language is life-giving. I think every generation has a version of that struggle. If you take the Gospel seriously, you can't get away with offending other people for their faith; that would be denying what we say we believe. So how do you deal with that? An increasingly common answer seems to be just not to talk about it. That's kind of where we land.

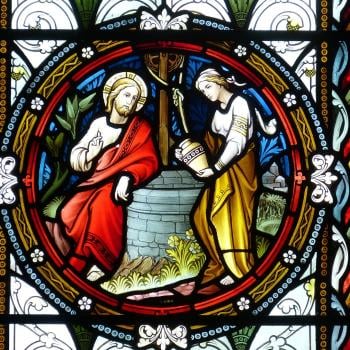

You also make an interesting comparison in your book between the religious pluralism of our time and that of the 2nd and 3rd centuries. You suggest there is something we can learn from Christians living in that time whose identity was so radically focused on Jesus.

Christianity was a tiny religious minority then and what made people notice the church was their distinctive way of life. People said: See how they love each other? See how they take care of each other? See how they are giving alms to the poor and hospitality to strangers? See how they welcome people into their homes? It was so startlingly different from the way the general culture lived that it was noticeable, even with this little tiny group of people. Everyone wanted to know: what gave these people their dignity? Their courage? Their hope? Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder talks about being a witness to the waiting world. By being ourselves, the church, that's the witness.