By Greg Garrett

History matters. It tells us how we got to where we are, and it can predict what will happen if things continue unchanged. But it doesn't necessarily tell us what will happen if the equation is altered, if radical systemic change takes place. In the recent interview with my Baylor University colleague Rodney Stark ("Are Evangelicals the New Mainline?"), Rodney has summarized with his customary verve and intelligence why mainline Protestant denominations in America have gone into decline, and spoken with passion about what is going well within evangelical churches.

History matters. It tells us how we got to where we are, and it can predict what will happen if things continue unchanged. But it doesn't necessarily tell us what will happen if the equation is altered, if radical systemic change takes place. In the recent interview with my Baylor University colleague Rodney Stark ("Are Evangelicals the New Mainline?"), Rodney has summarized with his customary verve and intelligence why mainline Protestant denominations in America have gone into decline, and spoken with passion about what is going well within evangelical churches.

I live in both these worlds. I was raised Southern Baptist, I also attended evangelical Methodist and charismatic Assembly of God Churches in my childhood, and I have taught for over twenty years at historically-Baptist Baylor; on the other hand, I am a seminary-trained Episcopal lay preacher in my current life after many years outside Christianity, and I often speak, teach, and preach in Episcopal, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Methodist, and Congregational settings. When reading Rodney's interview, for the most part, I can only nod, say he's right, and look forward. If we accept as a given the formulation that bigger is better (that is, larger or growing churches and denominations are more successful and presumably more faithful than smaller or declining ones) then the numbers and the history certainly bear him out: Evangelicals, 1. Mainline Protestants, 0.

Evangelicals now hold the same sort of cultural and political power mainline Protestantism once monopolized. When people identify themselves as church-goers, they are much more likely to be evangelical, most of the nation's largest churches are evangelical, and when people today think of Christians, most do not think of the Frozen Chosen in the Presbyterian Church on the corner, but of the active and vocal evangelical Christians demanding their say in the public square. However, there are cracks in this façade, and although I do not wish it, history, as Rodney has presented it, may also predict the decline of evangelical Christianity in America as well unless some things change.

It may, in fact, already be happening. Several studies have shown that Americans aged 18-49 are disconnected from Christianity in ways earlier generations have not been, and that they are largely turned off by their perceptions of the legalistic and political dimensions of conservative Christianity. Evangelical Christianity will not appeal to these unless one or the other changes. Lifeway, the publishing organ of the Southern Baptist Convention, the nation's largest Protestant denomination, released a study in April of this year that found that the denomination had lost tens of thousands of members over the last few years. And some surveys suggest that membership figures in evangelical churches are wildly inflated to begin with (they certainly were in my youth), so we may not know how many people we're talking about in the first place.

Some of these are simply methodological questions. This much is true: evangelicals are the American mainstream these days, but I fear that evangelicals may join Catholics and mainline Protestants in decline unless they pay attention to the points that Rodney makes about the history of the mainline.

Spirituality -- not just church attendance -- matters. Evangelical faith is often wide but not very deep; a nonspiritual Christianity does not sustain, and as Rodney says, there is little reason to worship or believe in a God who does not exist in one's daily life. The evangelical Barna Group discovered that many evangelical churchgoers do not have a sustaining faith and practice in their everyday lives; they are religious, George Barna tells us, but not spiritual. This is a recipe for impending disaster.

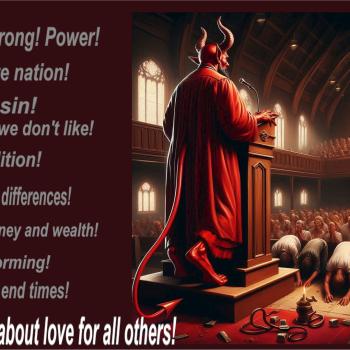

Likewise, a passion for justice -- whether one pickets for unborn babies or born babies -- must draw from a well of authentic faith and belief to be sustaining. When churches make political issues -- or moral issues -- their defining characteristics, then they often fail, deservedly. If my evangelical brothers and sisters become political at the expense of their faith in the reconciling and transforming love of Jesus Christ, than we might be speaking of them fifty years hence as a part of the great Christian decline.

I hope not. There is much we can learn from each other. Mainline churches need to learn (and are learning) to be evangelical, in the best sense of the word. They need to speak of the power of community in Christ, to speak of (not just demonstrate through charity or good works) the love of God to a world needing healing and wholeness. Episcopalians, I discovered when I became one, have no recent history of evangelism; no wonder we are in decline! When churches feature leaders who don't speak the name of Jesus from the pulpit, when church members don't speak about their churches or their faith to others, and when churches become merely union halls or political action centers, then the passion and the Spirit depart. The evangelical tradition can teach mainline Protestants how to be a lighthouse in a darkened sky -- and those methods can be adapted to things with which we're comfortable. I would not leave a Chick tract in a public restroom or ask my seat mate on a plane if they "know the Lord," but I would invite people to experience a U2charist at my church, and I should. Good things happen when love and God are made manifest in people's lives.