Sometimes the things you've done a thousand times can bring new results; the prayers you've said a million times bring new insight.

Sometimes the things you've done a thousand times can bring new results; the prayers you've said a million times bring new insight.

My Oratory has an assortment of Holy Icons and small pewter statues, and an old standing crucifix. As I begin my morning prayer, I ponder what is before me. Currently before the crucifix is a small pile of tumbled stones, reminding me of the question, "Who will roll away the stone?"

My Oratory has an assortment of Holy Icons and small pewter statues, and an old standing crucifix. As I begin my morning prayer, I ponder what is before me. Currently before the crucifix is a small pile of tumbled stones, reminding me of the question, "Who will roll away the stone?"

I like the question because it reflects our daily vulnerability and anxiety, our daily quandary: I have these plans; how am I going to accomplish them? What can I do of myself; with what do I need help? On what or on whom am I wholly dependent in order to do some things?

The answers are always the same (I know the plans I have for you . . . ) and yet different, too. What do you choose to surrender (pride, control, feelings, things)? What do you choose to hold on to (usually, the same)?

What do you really ask?

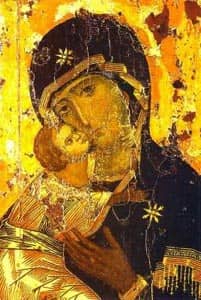

Beginning prayer at the oratory generally means letting my eye and attention slowly wander over the whole; eventually, as my prayer deepens, either my eyes will close, or they will focus on something which I have "seen" a million times before, but with fresh perspective. Recently, I began the Joyful Mysteries of the Rosary, and a simultaneous study of the Vladimir Theotokos ensued throughout:

Creator and created, sharing the same flesh, the same blood, entwined, together. The whole story, right there.

Creator and created, sharing the same flesh, the same blood, entwined, together. The whole story, right there.

The Annunciation: Since Eden, God's purpose—slow and baffling, yet inexorable—has been to restore all things in Him. There are so many things we do not know. Mary is hailed as "full of grace," born without the stain of the "necessary sin of Adam," which has set Gabriel his task: will she consent—she full of grace, yet free—to be the Ark of a New Covenant, the Host for the Lord of Hosts, who needs her flesh and blood before he can shed his own as the spotless Lamb, the acceptable sacrifice?

We always assume that this was the first time this question had been asked, and perhaps it was; perhaps the human campaign needed to be where it was, before the New Ark could be created in grace. But what if other young women had been similarly graced, earlier, yet were unable—in their freedom—to manage the fiat, the complete detachment from the opinions and schemes of the world, which would allow participation in God's difficult, mysterious scheme? Grace gives us the ability to believe, to trust and go forward, but we shrug off grace all the time in order to go our own way, satisfy our own minds, serve our attachments. It does not matter if other virgins had been privileged with a similar visit by Gabriel; Mary said "yes." That is what matters. Not knowing the Mind of God, she could not know that her act of surrendering flesh and blood would find its mirror and completion in another such surrender of what is (again) her own flesh.

The Visitation: Mary visits her cousin, Elizabeth, who rushes to greet her and cries out with mysterious knowledge: "whence does the mother of my Lord come to me?" Mary blooms into a prayer that echoes Hannah. In Elizabeth's womb, the forerunner leaps for joy! Flesh-and-blood recognizing flesh-and-blood, but alive with something more, something as yet undefined. The human family is yet mystical, and God's own, shouting out in discovery of oneness.

The Nativity of Our Lord: And then there is a crack in history as the God of Israel does something unthinkable; he becomes enfleshed and sets his tent with us. He does not come as an oddity, as a "better," or as something unrecognizable, demanding the fear and obsequiousness of all in his path. He is born of flesh, born of blood; Mary's own blood runs in his veins and he is wholly her own, yet wholly the world's.

He condescended to enter into the pain and fear, the tumult and whirlwind of the world and he "set his tent among us," not merely "dwelling" among us as lofty king, but literally "with" us, with hunger, the capacity for injury and doubt.

God entered in, not with a cacophony of noise and a display of raw power, but as the humblest and most dependent of creatures: a baby, lying in a manger, a place for the feeding of animals. He, who became Food for the World, entered with silence, as though he had put his finger to the quivering mouth of a troubled, sobbing world and said, "Shh . . . it is all right, I'll keep you company . . . "