When George Bernard Shaw first learned of the creative licenses taken in an effort to make the ending of his play Pygmalion more marketable, he was outraged. Confronted by Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree's claim that "My ending makes money, you ought to be grateful," he responded (with his trademark sharpness of wit and tongue): "Your ending is damnable; you ought to be shot."

When George Bernard Shaw first learned of the creative licenses taken in an effort to make the ending of his play Pygmalion more marketable, he was outraged. Confronted by Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree's claim that "My ending makes money, you ought to be grateful," he responded (with his trademark sharpness of wit and tongue): "Your ending is damnable; you ought to be shot."

Two years later, still stinging from the change, he penned a 5,000-word essay—"Sequel: What Happened Afterwards"—in which he emphatically (and bitingly) defended his original ending. In it, he argued that any version that returns the transformed Eliza Doolittle to Professor Henry Higgins' home is undermining the very core of the play's message, tossing away the power and relevance of his modernized myth for the sake of a cheapened and shallow emotional payoff.

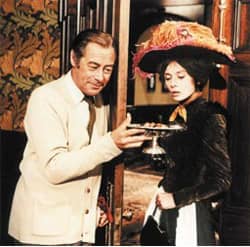

Interestingly, neither big screen version of Shaw's most famous work features his intended ending. In both 1938's Pygmalion(made with the approval and assistance of Shaw himself) and My Fair Lady (the famous musical version from 1964), Higgins and Doolittle are reunited in the film's final scene. Yet despite the fact that much of the two films' language is identical, Lerner and Loewe's version manages to avoid the cheap and shallow finale, while Pygmalion, despite its undeniable charms and wonderful performances, is rooted in Shaw's aforementioned "damnable" territory.

The most obvious reason for this dramatic difference is the contrast between the two actresses playing Eliza: Wendy Hiller and Audrey Hepburn. Both bring a wonderful vivacity and charm to the role; both are clearly at ease with Shaw's nimble, sharp-edged dialogue; and both serve as the perfect foil to their respective Higginses. Yet the unique aspects of their performances are striking, dramatically altering the tone and focus of the two films.

When Rex Harrison lobbied My Fair Lady's producers to allow his stage co-star, Julie Andrews, to play Eliza, he suggested that Hepburn's background—her mother was a Dutch baroness—made her unfit to play the early, draggle-tailed guttersnipe stages of the story's heroine. And while Harrison subsequently recanted his view, proclaiming Hepburn to be his favorite leading lady, his reservations are at least partially born out: Hepburn belongs in the high society to which Professor Higgins elevates her. Her Eliza is a diamond-in-the-rough; Higgins' relentless cutting and polishing brings out her full luster, producing a lady that would make any finishing school proud. Even the famous Ascot Race Track scene, where Eliza reveals herself to be unprepared for high society in the most spectacular fashion, underscores her grace and charm. In the midst of such an overwhelming, surreal display of British ostentatiousness, her slip is more amusing than it is damaging, and the audience finds itself easily overlooking the indelicate reminder of her low-class roots in the face of her undeniable magnetism.

When Rex Harrison lobbied My Fair Lady's producers to allow his stage co-star, Julie Andrews, to play Eliza, he suggested that Hepburn's background—her mother was a Dutch baroness—made her unfit to play the early, draggle-tailed guttersnipe stages of the story's heroine. And while Harrison subsequently recanted his view, proclaiming Hepburn to be his favorite leading lady, his reservations are at least partially born out: Hepburn belongs in the high society to which Professor Higgins elevates her. Her Eliza is a diamond-in-the-rough; Higgins' relentless cutting and polishing brings out her full luster, producing a lady that would make any finishing school proud. Even the famous Ascot Race Track scene, where Eliza reveals herself to be unprepared for high society in the most spectacular fashion, underscores her grace and charm. In the midst of such an overwhelming, surreal display of British ostentatiousness, her slip is more amusing than it is damaging, and the audience finds itself easily overlooking the indelicate reminder of her low-class roots in the face of her undeniable magnetism.

Hiller, on the other hand, is a hard-working, undereducated-but-overachieving flower girl, not a diamond. Her Eliza is better suited to her original lowly condition than her "creator" realizes, and the professor's efforts on her behalf feel much more like the construction of an elaborate facade than they do the revelatory polishing of a fine jewel. She does not belong in the world of bright lights, flowing gowns, and high society into which her Higgins (Leslie Howard) so self-indulgently places her, and when she arrives at her final triumphant test, the Embassy Ball, Heller radiates terror, not confidence. Her tearful appraisal that, "I sold flowers, I didn't sell myself. Now you've made a lady of me, I'm not fit to sell anything else" rings true. Higgins has created a fish-out-of-water, a woman problematically altered by his efforts to reshape her in the latest socially-acceptable image rather than simply elevated and transformed.

Hiller, on the other hand, is a hard-working, undereducated-but-overachieving flower girl, not a diamond. Her Eliza is better suited to her original lowly condition than her "creator" realizes, and the professor's efforts on her behalf feel much more like the construction of an elaborate facade than they do the revelatory polishing of a fine jewel. She does not belong in the world of bright lights, flowing gowns, and high society into which her Higgins (Leslie Howard) so self-indulgently places her, and when she arrives at her final triumphant test, the Embassy Ball, Heller radiates terror, not confidence. Her tearful appraisal that, "I sold flowers, I didn't sell myself. Now you've made a lady of me, I'm not fit to sell anything else" rings true. Higgins has created a fish-out-of-water, a woman problematically altered by his efforts to reshape her in the latest socially-acceptable image rather than simply elevated and transformed.

In the "Tea with Mrs. Higgins" scene, with dialogue later used by Lerner and Loewe in the Ascot Race Track setting, Eliza is allowed to make a spectacle of herself in the very surroundings most unsuited to her. Rather than a charming young girl whose social faux pas are masked by the high-hatted spectacle of the race track, we have the inescapable simplicity of Mrs. Higgins' parlor, where Eliza's errors are far more obvious and Professor Higgins' indifference to (and even amusement in) her discomfort far more damning.