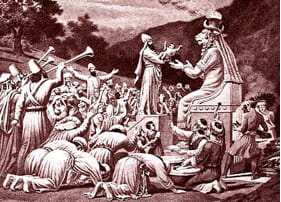

I don't remember the first time that I heard a priest make a comparison in his homily between the abortion-on-demand regime of the late 20th-century and the ancient Mediterranean cult of infant sacrifice associated with the worship of the demon Moloch. I do remember that the first time I heard the suggestion, I thought it far-fetched, a tasteless exaggeration: of course, abortion is a horror, but the killing of the unseen unborn in utero is at least slightly less ghastly than the ritual sacrifice of postnatal infants, plump little cherubic children who have already been born, swaddled, and suckled, right? And the reasons why we moderns commit abortion are selfish, banal, and unremarkable; there's just something much more monstrous about believing that a Canaanite deity wants your baby, that killing a child will bring supernatural blessings upon you and your family.

I don't remember the first time that I heard a priest make a comparison in his homily between the abortion-on-demand regime of the late 20th-century and the ancient Mediterranean cult of infant sacrifice associated with the worship of the demon Moloch. I do remember that the first time I heard the suggestion, I thought it far-fetched, a tasteless exaggeration: of course, abortion is a horror, but the killing of the unseen unborn in utero is at least slightly less ghastly than the ritual sacrifice of postnatal infants, plump little cherubic children who have already been born, swaddled, and suckled, right? And the reasons why we moderns commit abortion are selfish, banal, and unremarkable; there's just something much more monstrous about believing that a Canaanite deity wants your baby, that killing a child will bring supernatural blessings upon you and your family.

Ancient demonic baby-sacrifice is a far greater horror than the clinical commonplace of abortion. Isn't it?

Two things have persuaded me otherwise. One is reflecting on the German philosopher Hannah Arendt's (1906-1975) famous thesis about the "banality of evil": that while the screaming, spittle-spewing, fist-waving fury of the Führer might get all the attention, the dull, bureaucratic, 9-to-5, desk-bound administrator who manages the deportation and gassing of thousands from his office in Berlin is just as evil—and is perhaps even more of a monster because of his lack of passion. Hannah Arendt has persuaded me that the greatest horrors of our age could indeed be perpetrated by a chain-store business, with storefronts tucked between hot dog joints and low-end law offices, and a brand logo as recognizable as McDonald's:

I must credit another German with additional insight into the cult of Moloch, and its kinship to abortion: the writer Thomas Mann (1875-1956), who wrote a four-volume novel sequence called Joseph and His Brothers, in which the familiar tales of the Hebrew patriarchs, told so tersely in the book of Genesis, are turned by Mann into the language of modern, psychological realism over a sprawling work of more than 1400 pages.

I must credit another German with additional insight into the cult of Moloch, and its kinship to abortion: the writer Thomas Mann (1875-1956), who wrote a four-volume novel sequence called Joseph and His Brothers, in which the familiar tales of the Hebrew patriarchs, told so tersely in the book of Genesis, are turned by Mann into the language of modern, psychological realism over a sprawling work of more than 1400 pages.

In Mann's retelling of the story, the young Jacob comes to the house of his uncle Laban, father of his future wives Leah and Rachel:

Towered over by several tall poplars—the bark of one had been split from top to bottom by lightning—the house was a rude structure of fairly modest dimensions and made of clay bricks already crumbling a little, but its airy upper floor lent it a certain architectural charm; for the roof, covered with a layer of earth and furnished with a few reed sheds, rested directly on masonry only at the center and the corners, while the rest was set on wooden posts. It would be better to speak of several roofs, for the house was open in the middle and formed a quadrangle of four wings surrounding a small courtyard. A few steps of well-trodden clay led to the palm-wood door . . .

The women had descended from the roof and were awaiting their lord and his guest in the front hallway, onto which the house door opened and into whose plastered clay floor had been set a great mortar for pounding grain. Adina, Laban's wife, was an unprepossessing matron with a necklace of gaudy gemstones, a headscarf draped over her tight-fitting cap and covering her hair, and a face whose joyless expression was reminiscent of her spouse's, except that the set of her mouth was not so much sour as bitter. She had no sons, and that may well help explain Laban's gloominess as well. Later Jacob learned that early in their marriage the couple had indeed had a little son, but that when building the house they had sacrificed him by burying him alive in its foundation inside a clay pot, along with lamps and keys, so as to call down from on high blessing and prosperity for both house and farm. Not only had the offering not brought any special blessing, but ever since Adina had also proved incapable of giving birth to boys.

In Thomas Mann's imagination, the cult of Moloch is transformed into the unremarkable and commonplace, like burying a statue of St. Joseph in your yard: after extended paragraphs of architectural detail about Laban's house, we get one more detail, a jar with a little skeleton in it, tucked among the stones beneath the floor. I find it entirely convincing: the banality of evil, c. 1800 B.C.