(At our Empty Moon Zen half day intensive meditation retreat, Roshi Edward Sanshin Oberholtzer gave the talk. He’s the resident priest and guiding teacher at the Joseph Priestley Zen Sangha in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, as well as guiding teacher at Empty Moon Zen. He reflected on the fourth of Dongshan’s Five Ranks. Frankly, it took my breath away. I asked if I could reprint it here at my blog and he graciously consented…)

Our old friend, Dongshan, will not be repressed. After following him through a series of examinations of the interplay of the particular and the absolute, of the particular emerging from the absolute, the absolute found within the particular, of the absolute alone, we come to his fourth rank, Hen Ju Shi, going within together, the particular, the just this. And, as we have come to expect, Dongshan illustrates this with a poem:

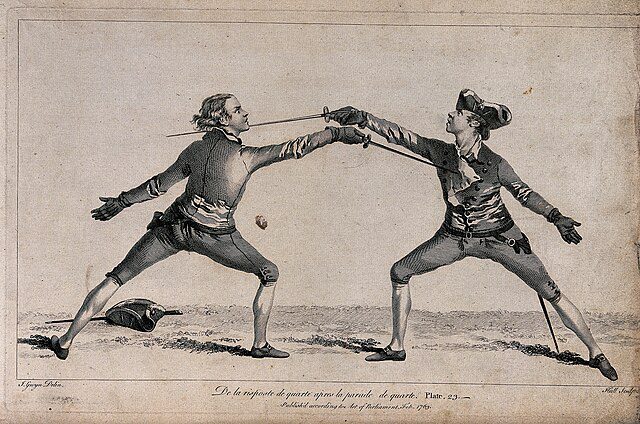

Two swords cross points, neither can turn aside.

The skillful hand is like a lotus in the fire.

Just as it is, this actualizes heaven’s resolve.

Perhaps the following will help in unpacking Dongshan’s brief verse.

Now, I needn’t remind you that a single starling is an incredible creature. Small, compact, iridescent, bright eyed. I’ve seen them scampering about the bird feeders out back, taking their turn getting to the seeds, unlike the bluejays, which seem to elbow everyone out of their way. Maybe its that starlings recognize that they’re an invasive species, not meant to be here, brought over towards the end of the nineteenth century by a Shakespeare fanboy and supposed conservationist who wanted to introduce every named bird in the Shakespearean oeuvre to the North American continent.

It’s not just in their seeming singularity, no, starlings, and here I emphasize the plural, starlings have another quality. I saw this best from my front steps in the first house my wife and I rented in west Cambridge. There at the top of the hill edging Fresh Pond, the bare trees of winter would take on a shimmering, a living quality. If my eyeglasses were better I might have seen that the branches were covered with the tiny forms of a myriad of starlings, all of them chattering so loudly that I could hear them even a quarter of a mile away even if I had difficulty making out individuals visually. Suddenly, like two swords crossing points, with neither of them able to turn aside, the sound would cease and, a moment later, the entire mass of birds would rise into the air, a black swirling cloud, undulating rythmically, moving as though it were itself a living, breathing thing. and, just as suddenly, that dark cloud of thousands upon thousands of birds would gather up and fall into place back on those bare tree branches, a vision of the absolute emerging from the particular.

I still marvel at how the individual acts of those tiny creatures can give rise to such wonderous masses of blackness pulsing against the grey winter clouds. I’m sure that there are explainations grounded in simple algorithms that each bird must follow, how to turn when the birds on either side of it alter their course., what to do when it becomes aware of the motions of birds in front, above, below. Explanations though, do not remove the wonder, a wonder heightened by the certainty that if by some miracle, you could reach out into that flock and hold one single starling in your hand, it would, for all its membership in the vast collective, still be that simple, bright-eyed, seed eating little bird. Just this.

There is a kind of magic that emerges when a group of creatures comes together, a magic captured in that compendium of collective nouns, a book I long thought could only be loved by librarians, a book entitled An Exultation of Larks, where we learn that the writhing, massive flock of starlings is simply called a murmuration, that a similar grouping transplanted into the ocean, is of course, a school of fish, a school with the seeming ability to stop and turn on a dime. An Obstinacy of bison that once blackened the plains. And, while each bird, each fish, each buffalo, each fly in a swarm of flies, each one of those animals is a unique, distinct, particular individual, the collectives that emerge only really hint at the universal, the absolute that they embody. Nonetheless, they do seem to lean in that direction, even if they are composed of those simple, particular birds, whose fellow creatures can be found, chattering away on my back porch.

But look, really, truely look. That sparkling, white field of snow, that universe of whiteness is made up of millions of crystaline snowflakes, each as close to unique as one might ever hope. That torrential downpour consists of a myriad of raindrops, each a world, a universe unto itself. That swirling mass of fish, seemingly with a mind of its own, able to turn in an instant, to split and to merge, that mass is nothing but thousands, tens of thousands of individual, particular, shimmering distinct fish, each one a marvel, each one a part of the whole.

It’s funny how we can name a collective, but we can’t really point to it. Pointing seems to be a characteristic of the particular. How can you indicate the universal with something? We can plan a day at the beach, but when we reach down and take a handful of that beach it’s individual grains of sand that fall through our fingers.We can name an army, but when we point, we can only indicate individual soldiers. One of my icons as a social sciences librarian was a man named Edward Tufte who made a cottage industry of writing books on how to visually portray statisitics in an understandable way. One of the most striking maps that he included in his book The Visual Display of Quantatative Information was a nineteenth century map of the advance and retreat of Napoleon’s army into Russia. It allowed you to watch as the army, once vast and seemingly invincible, gradually shrink after running up against Moscow’s defenders, dwindling into ever thinning ranks as it retreated against the Russian army and the Russian winter. It was an army seen as the thickness of an inked line, but an army of individual, suffering soldiers. If you could go back in time, if you could sink into that blackened line on the map, you would find not an army, but particular citizens of the French Empire, men (and perhaps women) who lived, breathed, bled, and froze, specific individuals with families, with spouses, with children, men who, collectively were called an army. You will often find it observed that on the front lines of any conflict, soldiers fight not for ideologies, but for one another, their skillful hands, if we may turn back to Dongshan, are like a lotus in the fire. Armies may loom in the imagination, but it all comes back to that individual, frightened grunt.

There are three dharma bodies. The Dharmakaya, the realm of the absolute, The Sambogakaya, the realm of the mysterious, the realm of the dance, and the Nirmanakaya, the particular, the distinct, the realm of the historical Buddha. Once, in dokusan, one of my Boundless Way teachers, responding to my then position as tenzo as the cook for the retreat, told me that my dharma body was the nirmanakaya. It seemed to me a pretty astute observation, and, if I might quote the final words of Dongshan, Just as it is, this actualizes heaven’s resolve.What might be more particular that weighing out rice, measuring salt, beans and soy sauce?

All of those small, particular, individual parts of a meal are all part of the meal service, are all part of the feeding of the Sangha, are all part of the Sangha, are all part of the absolute. But it is in those individual serving spoons of rice, those individual carrots and pieces of bread, those individual and very distinct shakes of a soy sauce bottle that that our meal service is made, that we use to make our offerings to the hungry ghosts, that we invoke Vairochana Buddha, pure Dharmakaya; Lochana Buddha, complete Sambhogakaya; Shakyamuni Buddha, myriad Nirmanakaya; Maitreya Buddha, of future birth; and all the rest.

The great cloud of unknowing, the mysterious absolute, the whole of the Dharma, comes down to just this; the starlings, the fish, the grains of sand, those frozen French soldiers limping back across the steppes of eastern europe, the spoonfuls of rice in your oriyoki bowl. These individual, particular, distinct instances are all pointed to, are all those unique parts that Dongshan finds in his dive deep into form and emptiness. And yet, and yet……..