It's not every day that BYU is accused of being "infected" with liberalism. But that is exactly what Utah-based artist Jon McNaughton pronounced a few weeks ago when he claimed BYU's bookstore "censored" his artwork by refusing to sell one of his controversial paintings. In response, McNaughton pulled the rest of his work from the bookstore.

It's not every day that BYU is accused of being "infected" with liberalism. But that is exactly what Utah-based artist Jon McNaughton pronounced a few weeks ago when he claimed BYU's bookstore "censored" his artwork by refusing to sell one of his controversial paintings. In response, McNaughton pulled the rest of his work from the bookstore.

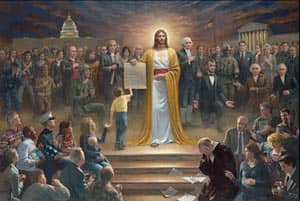

The work in question, One Nation Under God, depicts Jesus Christ holding the Constitution, flanked on either side by historic figures McNaughton deemed worthy of Christ's Second Coming. To Christ's right hand and below his feet are the revered and triumphant disciples who represent McNaughton's ideal citizens, including a valiant marine, a humble school teacher, a Cleon Skousen-touting college student, and even a farmer ("truly the backbone of America"); on the left hand of the Savior sit an activist judge, a liberal news-reporter, a lawyer, and a smug college professor clinging to Darwin's Origin of Species. McNaughton, for his part, is surprised that his painting causes discomfort. "It's only offensive to people who do not believe the Constitution is divinely inspired," he told the Salt Lake Tribune.

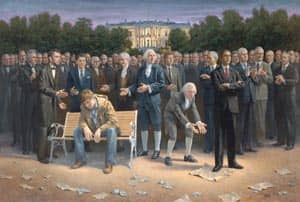

Parodies of McNaughton's art abound. One Nation Under God—as well as his more politically charged Forgotten Man, which depicts Barack Obama stepping on the Constitution to the astonishment of the Founding Fathers—has been covered in many venues, and the resulting tiff with BYU has only perpetuated its humorous appearance. For many, McNaughton's paintings serve as a caricature of the extreme right and give credence to generalities often placed on the Tea Party.

Parodies of McNaughton's art abound. One Nation Under God—as well as his more politically charged Forgotten Man, which depicts Barack Obama stepping on the Constitution to the astonishment of the Founding Fathers—has been covered in many venues, and the resulting tiff with BYU has only perpetuated its humorous appearance. For many, McNaughton's paintings serve as a caricature of the extreme right and give credence to generalities often placed on the Tea Party.

But, surprisingly to many, McNaughton's art resonates with a large segment of the American public. As difficult as it is to take his art seriously, the art provides a key to the current mindset of many in the religious right. McNaughton's paintings represent a deeper ideology that seeks to restore an understanding of America's greatness by grounding art, history, and religion in an all-encompassing fundamentalist political mindset.

The Merging of Religion and Politics

The Merging of Religion and Politics

The fact that McNaughton and many of his followers have trouble labeling One Nation Under God as a "political" work can appear striking. Negative depictions of a "liberal news reporter" or an "activist judge" seem political enough to many, but to this segment of society they are self-evident truths as obvious as Christ's divinity. Put simply, McNaughton does not see his painting as being an outright political statement because his political and religious views are so intertwined that they cannot be separated. The fact that Obama is a socialist and dangerous to America is just as much a part of McNaughton's religious worldview as the fact that the Constitution was inspired.

In their recent book American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, political scientists Robert Putnam and David Campbell observed that, while conservative religious congregations were less likely than liberal congregations to make overt political statements, there was no need to do so because they were already assumed. Indeed, in the book's surveys, those on the right were much more likely to admit an influential connection between their political and religious views, and to admit that the two views fed into each other. Ever since the 1970s, American Grace tells us, there has been a growing fusion between religion and conservatism on the one hand, and secularism and liberalism on the other.

McNaughton's art exemplifies the current phenomenon of blending religion and conservatism to such a degree that the two become inseparable, all based on the assumption that the one always leads to the other. This sort of political and religious conflation is especially the case within the LDS tradition. McNaughton certainly derives from this tradition, which has for the last century been strongly attached to the Republican Party, making the Mormon-dominated state of Utah among the reddest in the nation. In McNaughton's painting, America's leading figures worship not only the Constitution, but also Jesus; they recognize not only American exceptionalism, but also Christianity's supremacy. His art is perhaps the culmination of an extreme conservative trend within Mormonism, and BYU's decision to pull the painting possibly represents a decision that the trend has gone too far.