The X-Men, Marvel Comics' mutant superheroes, came onto the American scene in 1963 in the midst of the Cold War and the Civil Rights struggle. The basic premise of the series has proved to be long-lived, and, unfortunately, ever-topical: In a world of fear, prejudice, and violence, how do individuals who are shunned as different react to the fear and violence directed toward them? Through the decades, X-Men has been on one level an allegory about prejudice—first racial prejudice, more recently prejudice toward LGBT individuals, and now, perhaps, even a reference to Islamophobia. Through it all, as hard as that decision has been, the majority of these mutant heroes have chosen to protect and engage the very people who might in different circumstances destroy them—a very spiritual (and even Jesus-y) message.

X-Men: First Class (directed by Matthew Vaughn) reboots the film franchise by going backward to 1963, but the heart of the movie is—still—the reaction mutants have to a world that hates and fears them. Vaughn recently told MTV that the movie's emotional and ethical core is "that very important point of their lives where [the X-Men are first] discovering their power and working out their ethical take on what to do with their power." The X-Men themselves (in this film, the super-powered characters include the super-agile Beast [Nicholas Hoult], the shape-shifter Mystique [Jennifer Lawrence], the sonic-powered Banshee [Caleb Landry Jones], and the energy-projecting Havok [Lucas Till]) know that they are different. As ever, they lament their difference, feel their exclusion. Beast vocalizes to Mystique their common feeling: "You have no idea what I'd give to feel . . . normal."

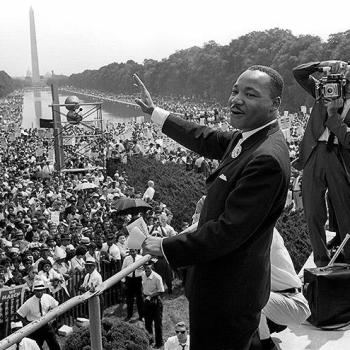

Prejudice can be confronted in different ways, as we know. The film's hero Charles Xavier (James McAvoy) resides in the Martin Luther King, Jr. camp. So far as possible, mutants must employ peaceful means to resist the hatred directed against them; they must use their talents to benefit the larger society, and perhaps, someday, it will be possible for all to live in peace and harmony.

His friend Erik Lensherr (Michael Fassbender), who will evolve into the arch-villain—and Xavier's nemesis—Magneto, is in the Malcolm X camp. Mutants must protect themselves by any means necessary. If it takes offensive power, that is simply a form of self-defense against hostile humanity. "Homo sapiens will hate, fear, and destroy us," he warns Xavier.

And certainly there are those who will—and do. In words reminding us of legal niceties in the Civil Rights era—or today in the Defense of Marriage Act era—a government official in the film snarls, "The law applies to human beings. Not to mutants."

This idea of unequal treatment under the law—and of possible persecution under the law—is a part of X-Men lore. In the 1980s, Magneto was revealed—it is also referenced in the X-Men films, including this one—to be a Jewish Holocaust survivor whose family was slaughtered by the Nazis. Erik is, understandably, more than a little sensitive about prejudice, and prone to go directly to the "never again" mentality that still drives many militant Zionists. When his friend Charles Xavier counsels that "Killing will not bring you peace," Erik replies, "Peace was never an option." He has seen the worst of humanity, and finds it difficult to believe in the possibility of anything better.

Institutional prejudice has, in fact, driven the X-Men story since the beginning. In 1965, giant lethal robots—The Sentinels—were introduced as X-Men villains. Eventually these Sentinels became a U.S. Government project designed to eradicate mutants. In Uncanny X-Men 141 (1981; also available in the trade paperback Days of Future Passed), written by Chris Claremont, the U.S. Senate debates an anti-mutant registration act, while a possible future driven by the passage of that act depicts mutants in a holocaust future ruled by Sentinels where the few surviving mutants are forced to wear arm-bands designating their status and power inhibitors like dog collars. In that storyline, Xavier and the human geneticist Moira MacTaggart are called as expert witnesses in front of the Senate, and they agree that while Senator Robert Kelly, who has convened the hearings might be a good man, he is also afraid. Continuing the references to the Holocaust, Prof. MacTaggart whispers to Xavier, "Registration today, gas chambers tomorrow."