When I was in seminary, I began the practice of going on retreat. My spiritual director was the rector at a local Episcopal church and retreat center where I would go three times a year for one or two nights. Two of those retreats were usually working retreats—immersing myself in a large academic project for a few days while I looked out over the Tomales Bay near Point Reyes, California. I did my best work in that atmosphere away from the noise of the city, the bustle of my family and the demands of everyday life. The other retreat was just for me—long walks on the beach, journaling, praying, and reacquainting myself with silence, the unfathomable peace of God and the sheer joy of solitude.

My friends often looked at me with surprise. Other mothers of young kids remarked that they wished their husbands would let them go away for two days. I always felt a little guilty and slightly indulgent for leaving all my responsibilities to go do "nothing." However, there was a growing sense that I needed this time.

This past week, I took my first retreat in two years and was reminded again how essential this spiritual practice is for me. The world slowed down and I was able to think more clearly and give myself to focused prayer in a way that I find hard to access in daily life. I met with a spiritual director who helped me to give attention to where I am spiritually. I read books, made notes, brainstormed ideas and planned for the fall. I came home with a renewed sense of purpose, vision and motivation.

Retreats are ideal for my personality. A natural introvert, I am also a people-pleaser. So when I go away, I can be by myself and not worry about making anyone else happy. In my daily life, I spend a lot of time in social networking, so retreats provide a respite from the constant input and engagement that comes with e-mail, Twitter and Facebook. Also, I am a person who doesn't need a lot of order. As a pastor, mom, wife, runner, writer and artist, my life moves at a pretty chaotic pace that changes every day. When I go on retreat, there is something about the simplicity of a small room with just a desk, a bed and a lamp that brings order to my usual chaos and provides a different kind of space.

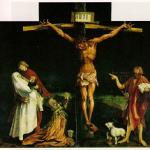

Since most retreat centers are run by Catholic, Episcopal, Orthodox or Buddhist groups, and many are a part of a religious community, retreat centers can also be a cross-cultural experience for many Protestants. Icons, crosses, statues of Mary, labyrinths, spiritual direction, and stations of the cross are not a part of our regular spiritual experience. These settings connect us to ancient roots of our faith that often go missing in contemporary worship services or worship spaces designed in the past 50 years. The unfamiliarity heightens our senses to see God, ourselves and the world in ways we hadn't before.

Walking around, there are multiple signs that invite quiet. The staff expects that you will rest and not produce anything. The Protestant work ethic is nowhere to be seen in a retreat setting where nothing but the slow pace of soul work needs to be done and where taking a nap in the middle of the day is always a good place to start. This change of pace forges new paths for the Spirit in our hearts.

When Thomas Merton left his monastery and visited the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville, Kentucky, he had an epiphany of God's love for each individual and was filled with the knowledge that we are all a part of each other. What Merton experienced leaving the monastery, I experience going into a monastery. There is something about the rhythm of religious life—the daily fixed prayer, the chanting of psalms, the unhurried routine, and the engrained hospitality that provides a new perspective and assures me of God's constancy. A former spiritual director encouraged me to maintain a relationship with a monastic community as a pastor and I am beginning to understand why. When I go into a monastery, I do not have to be "the pastor" and in that place, faith is lived out with a simplicity and daily discipline that is inaccessible in the ups and downs of pastoral life.

I believe that retreats will be essential to my health as a pastor. They are hard to take, seem indulgent and the calendar doesn't open very easily for 2-3 (or more) days away. However, if we can view them as essential to our health, vital to our mission and integral to our spirituality, they can become a part of our rhythm. Congregations need to give their pastor the implicit and explicit permission to take retreats and pastors must remember that the underpinning of all their work is the space for God in their own hearts, minds and bodies and that space takes intentional development. As we model the vitality of spiritual retreats, maybe our congregations will give themselves permission to regularly make this space as well.

7/13/2011 4:00:00 AM