The gospel reading for the Good Friday liturgy from John’s gospel begins with Jesus’s arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane and ends with Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus preparing Jesus’s body for burial and placing it in a tomb. Many Christmas Eves ago, Jeanne, our youngest son Justin, and I were invited to share dinner with a friend from work and her family, which included two precocious and very active children. On display was a beautiful crèche that contained all sorts of interesting items, including a duck and an elephant of roughly the same size. Our friend’s five-year-old daughter introduced Justin to the various characters in a monologue interrupted only by a few confirming comments. “And these are some shepherds, those are goats and sheep, that’s a dog a turkey and a cow, these are some angels, and that’s the baby Jesus.” “Oh, really?” “Yes. Actually, he died.”

The idea of a suffering and dying God is not new—there are many traditions older than Christianity that include myths and stories of a divinity suffering and dying for various reasons. But this story is so intimately personal, so representative of the crushed hopes and dreams, the inescapable pain and suffering, that are fundamentally part of the human experience. Jesus seemed to be something different but turned out to be the same as everyone else: human, limited, subject to suffocating power and injustice, to the random events that ultimately shape each of our stories.

In the religious tradition of my youth, our theology was what scholars call a “theology of glory,” one that emphasizes the power and glory of God as exemplified through Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of the world on Good Friday and his triumphant resurrection from the dead three days later. It is difficult to pay more than twenty-four hours of attention to the suffering and agony of the cross when you know that it all ends up in the right place. But what happens if the focus of one’s Christian faith is Good Friday rather than Easter? What is the difference between a “theology of the cross” and a “theology of glory”?

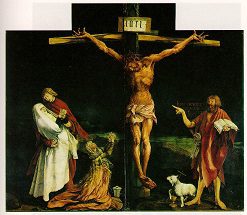

The Crucifixion without anticipating the Resurrection first moves our attention away from glory, power, and triumph, instead focusing us on suffering, pain, and weakness. This brings home the fundamental fact of Christian belief—God became human, with an emphasis on the human part—something that a theology of glory tends to de-emphasize. A few years ago I had a discussion with my monthly after-church adult education seminar group about the end of the Book of Job in the Jewish Scriptures, an ending that scholars say was tacked on long after the main story had been written, in which after more than forty chapters of suffering Job gets back everything that he had lost.

I asked the group why someone might have added this “happily ever after” ending to such a dark and human story. “Because the original ending is too tough,” someone suggested. “Because people want to believe that suffering has a point, that it is all for something,” another contributed. “Which makes the better story?” I asked. “The original is truer,” an eighty-something regular participant said. “People don’t come back. Things that you lose don’t return.” A theology that relies on a triumphant, happy ending is one that runs the risk of failing to address the human condition as we find it.

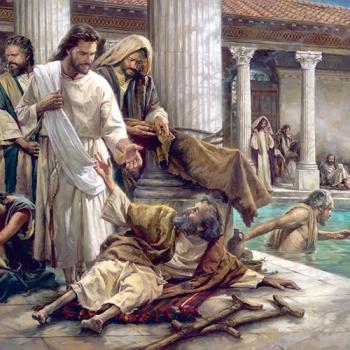

In contrast to a theology of glory, in a theology of the cross God addresses the human condition, not by overcoming it, but by becoming part of it. The divine is incarnated in human flesh and thus becomes subject to everything that human beings are subject to—including suffering and death. The Incarnation and the Crucifixion focus our attention on unlimited love, something that we often are too quick to move past in our rush to a happy ending. Good Friday reminds us that because of divine love the incarnated God did not seek to avoid this fundamental human experience.

Paul argues that the focal point of the Christian faith is the Resurrection: “If Christ be not raised, your faith is vain.” More foundationally, however, the Christian faith is vain if there is no cross, no suffering and death of the divine mediator between God and humanity. Only when we see, as did the penitent thief, that this criminal hanging on a cross, rejected and despised by all, is the perfectly just God-human paying the ultimate sacrifice to achieve mediation between God and humanity will we begin to truly experience the mystery of the Christian faith.

If the story ended with Jesus executed as a criminal and dead in a tomb, we still would have reason to believe in a God of love. The story of a God who becomes fully human, who lives a real human life subject to all things each human being is subject to, including suffering, pain, loss, tragedy, injustice, and death, serves to drive the point deeper. Good Friday reveals just how far the divine chooses to go with us—into the depths of despair and death. I once saw a poster with a dark twist on a familiar saying. “It is always darkest just before—it goes pitch black.” And God is there.

For reflection: Centuries of theological debate have centered on where one should focus one’s attention most strongly among the events of Holy Week. Which is more meaningful to your faith journey—Jesus’s death on the cross or Jesus’s resurrection three days later?