I've also heard Tyler, and much of Texas in general, is very conservative and very Christian. I have nothing against either, but I'm very liberal and an agnostic (in other words, not at all religious and not open to becoming so). My husband is also liberal and a Wiccan . . . our children are not religious . . . They're also very open and liberal in their beliefs. Neither kid has a racist bone in their bodies—seriously.

I don't want to stir up a huge controversy . . . I'm just worried that, given our beliefs, and even though we're pretty private about them, my family won't fit in there.

If someone is going to cross the street in this situation, should it be Tyler, Texas, or the family moving there from Wisconsin? We could ask the same thing about this long-time resident of Massachusetts:

Liberal dissent [sic] is the number one problem of the state. It has produced such a hatred and anger towards anyone that thinks differently. I have had rocks thrown at my car during this past election for supporting the Republican ticket, since I happen to be a Conservative Republican in this state. I had my car broken into, several lawn signs stolen off my lawn. A feminist group violently threatens me for not supporting gay marriage or pro-choice ideals . . . Can't wait to leave this place.

This may not be every conservative's experience of Massachusetts—just as there are probably plenty of agnostics who aren't concerned about what they'll find in Texas. But everyone has a background and a set of expectations. How do we decide who crosses the street and who doesn't?

The question might seem rhetorical, given that almost all of us really do prize intellectual tolerance. We prefer solutions that go something like this: "No one has to cross the street, but on the other hand, everyone does." We would endorse the idea that an agnostic and a Wiccan should be able to move to Texas without social discomfort, and that a conservative in Massachusetts should be safe from threats and vandalism.

But whether Bill Bishop's analysis explains it accurately or not, most of us also recognize that political sentiment is increasingly polarized in America. Some would say the situation is becoming unsustainable. The reason seems to lie in the aspect of the standoff that Bishop leaves unaddressed: the character of the beliefs on either side. If the differences between them didn't matter, we could sustain a polarized condition forever. But the "house divided" analogy, used properly, refers to differences in character so fundamental that they cannot coexist in the same entity or being.

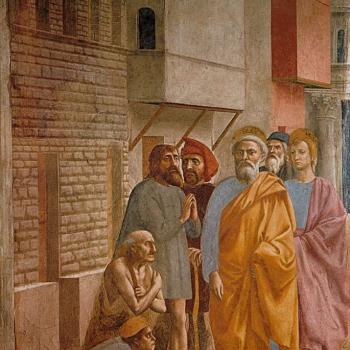

Jesus used the "house divided" metaphor (Mk. 3:22-27) to counter the accusation that he cast out demons with the power of Satan. Satan cannot be divided against himself. He is an irreducible unity. One cannot compromise with Satan; one can only overpower Satan. Abraham Lincoln invoked the passage in a somewhat similar vein. The United States could have only one character: it must be a union, and that union must repudiate slavery. In any other condition it would not be the United States. The coexistence of irreconcilable opposites was impossible; one side had to prevail and to impose its vision of the country.

Likewise, if the "house divided" analogy is applicable to America's political divisions, the remedy it indicates is, ironically, the opposite of compromise. If we are truly a house divided, "crossing the street" may more nearly resemble crossing the Rubicon: instead of temporizing or negotiation, preparation for victory or defeat. That sounds highly undesirable to a gregarious, well-intentioned people, as it should. In this context, it is worth pointing out that a good way to relieve the pressure on a divided polity is to keep government limited. You and your neighbor are less likely to have to cross the street—or the Rubicon—in order to negotiate or struggle over a power the government does not possess.