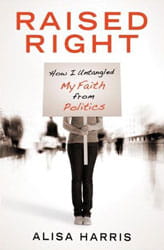

Unlike the biographies of the famous, memoirs are often written by everyday men and women seeking to process something, to decode their past and cobble it together with their present. The writing stands as an integral part of the process and not just storytelling in the aftermath. Alisa Harris, a young Christian and journalist, allows us to look over her shoulder as she traces and contemplates her still-evolving spiritual coming-of-age in her new memoir Raised Right: How I Untangled My Faith From My Politics. (Visit the Patheos Book Club on Raised Right here.)

Unlike the biographies of the famous, memoirs are often written by everyday men and women seeking to process something, to decode their past and cobble it together with their present. The writing stands as an integral part of the process and not just storytelling in the aftermath. Alisa Harris, a young Christian and journalist, allows us to look over her shoulder as she traces and contemplates her still-evolving spiritual coming-of-age in her new memoir Raised Right: How I Untangled My Faith From My Politics. (Visit the Patheos Book Club on Raised Right here.)

Raised in a strict Christian home, Alisa Harris grew up with parents whose small strip mall evangelical church rode the crest of the Religious Right's power years of the 1980s and early '90s. She stood outside abortion clinics as a child, outgunned her peers in a home school speech group to win a Ronald Reagan calendar, helped man GOP phone banks in election years, and exhibited a goat dressed as Bill Clinton at a county fair (Alisa was dressed as Hillary).

It's easy to dismiss Alisa and her family as over-the-top right-wingers and note her story as an interesting piece of Americana. But Raised Right tells the story of thousands like Alisa who still embrace the spiritual and theological faith of evangelicalism but reshape its living out and who will change the face of American Christianity over the next two decades.

This change invigorates and hurts at the same time. Stress fractures creep into what we once thought unshakeable, while dissatisfaction and disillusionment grow through like weeds poking up through a cracked sidewalk. Her deep respect for the faith of her parents and grandfather made Alisa look beneath the legalism of the churches around her. D. Michael Lindsay commented that the power evangelicals gained institutionally and culturally ambushed them. Power created empire. Alisa's parents just wanted to engage the lives of suffering people as followers of Jesus Christ. They saw the flaws, but an evangelical faith welded to empire building and political muscle seemed to be the only place to go. Her parents emerge as noble chapters in Alisa's story.

Other stress fractures included college experiences. Poems describing the carnage of modern warfare (Wilfred Owen on WWI) and human rights violation reports detailing horrific violence against women punctured the airtight compartment of her beliefs. She began to read classical writers to chew on their ideas. Although her school, Hillsdale College in Michigan, brings in the heaviest hitters in conservative thought, Alisa often skipped their appearances, discovering she was burned out on rhetoric. (For an account of someone moving from left to right, see David Horowitz's Radical Son.) Finally, at the Obama victory celebration, Alisa realized that no human being (even one she voted for) could deliver the deepest fulfillment of human hope.

Moving to New York, she discovered other evangelicals who felt the same way. She met Democrats whose ideas about their party matched her thoughts about the GOP. None of them were crazy about everything their party stood for. Alisa still stood for pro-life values, as evidenced by her writing for both World and Patrol magazines. But she began to shed light on human suffering issues outside the regular rhetoric surrounding abortion and homosexuality. Her work and her life in New York City also took her deeper into suffering "on the ground instead of in the statistics." Her journalistic work took her to experiences in other parts of the world that leave nightmares in the daytime. Alisa smelled the smells and saw the faces—up close.

Alisa Harris tells her own story and makes no claim to speak for anyone else. But she does. Many young adults, reared in the same spiritual cradle as Alisa, now reassess their religious convictions. Twelve Step groups sprout up and fill quickly to help people get over the restrictive spiritual abuse of fundamentalist Christian upbringings. Other memoirs written alongside Raised Right don't turn out as well. Even Christians as well known as author Philip Yancey talk about escaping the gravitational pull of caustic faith. L'Abri, a spiritual retreat network begun by Francis Schaeffer in the '60s, started out helping people burned out on hallucinogenic drugs and fed up with Tibetan gurus chew on the person of Jesus Christ. Now they draw young adults raised in evangelical youth groups who want to know if God is real. Pundits say that evangelicalism is going away. On the surface, it looks like it. But they're wrong.