GREELEY’S GOTHAM

By 1820, New York was becoming something of a “colony of New England.” Central New York (like Oneida) had already become practically as “Yankee” in population as Connecticut in 1800. More literate than the average New Yorker, the Yankee wrote most of the editorials and set most of the type in the printing houses. These “cocksure invaders” did not hide their contempt toward the “churlish, ignorant, and unenterprising” Germans and Dutch. These old New Amseterdamers fired back as best they could by circulating stories about “dirty Yankee tricks.” The upper classes read with delight James Fenimore Cooper’s novels “which invariably described the Yankees as a particularly disagreeable race.”[1]

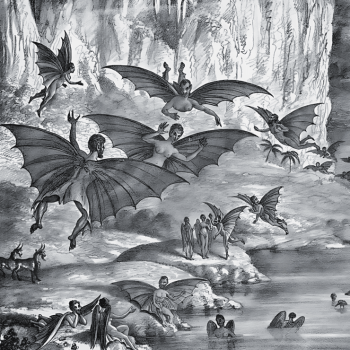

A young man named Horace Greeley was one such Yankee. Born in the small town of Amherst, New Hampshire in 1811, Greeley would eventually mature into a formidable thought leader. He still had some trials to undergo. After working as a newspaper apprentice in Vermont, Greeley set off for New York City in 1831.[2] His journey took him through the “Burned Over” regions of New England and New York. Religious revivals have been seen throughout all time and among all nations. A movement in the minds of the people; rapid, luminous, an enflamed quickening that comes, it seems, from out of the aether. Wearing itself out just as quickly.[3] Progenitors of a religious idea, agents of the unseen forces that disturb consciousness, carry, it seems, some electrical solution coursing through their brains. With wyvern breath they expel the words from their lungs, discharging their fiery burden. Sometimes a cry goes out from some village church, from some unknown lips, and a whole city or province glows white hot ecstatic. This is what happened in New Haven and New York in 1831. An outbreak of religious fervor began in the Northern States of the Union, and swept over the whole country like a cyclone, leaving its traces particularly upon New England and Western New York. No one knew for sure how the Great American Revival came about. Nobody “caused it.” Nobody could guide it. Nobody could stop it. No past revivals could vie with this Great Revival in length of time, vastness of geography, or strength of passion. Who can say where it first began? It has never been identified with a single name. It was the result of unknown efforts of unrecorded inspirations. This spiritual tempest crossed the Atlantic to England. Then it crossed the English Channel into Germany.[4] Among the many new Christian sects to emerge at this time was the “Millerites,” named in honor of the clergyman William Miller, a Millennialist who predicted that Christ would return in the year 1843.[5]

Politically, Greeley was a Whig, and hardly in agreement with the policies of Andrew Jackson.[6] The first President of the new Democrat Party, Jackson’s election in 1829 marked the beginning of the populist era known as “Jacksonian Democracy.” The name itself stemmed from the Greek, “demos krateo,” or “people’s power.”[7] It was a time of uncertainty for American society, characterized by rapid, unstable, economic change, social mobility, racial violence, anxiety over “rootlessness,” and fears of “mobocracy.” Andrew Jackson, the avatar of this age, was himself lauded as the quintessential “self-made” man. This sentiment, exemplified by unexamined actions and a rejection of the past, was especially felt among the emerging middle class of merchants, tradesmen, and entrepreneurs. It was what James Fenimore Cooper called “goaheadism.”[8]

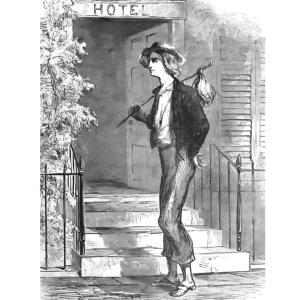

“Young Greeley’s Arrival In New York.”[9]

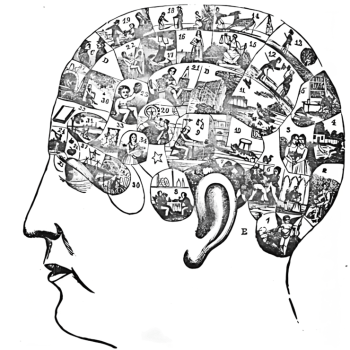

The social organism, in conversation with the aria of theological debates, developed organizational apparatus that helped to give direction to people suffering from the social strains of a population veering into new political, economic, and geographical areas. Innovations in printing, papermaking, and distribution, saw the rapid increase and spread of print culture. By 1822, America had more newspapers than any other country in the world. Magazine publishing, likewise, expanded dramatically for two decades beginning the 1820. This created a new, literate mass audience, and the institutions for a market economy focused on non-utilitarian literature.[10] The years 1825 to 1840 saw the beginning of the “country newspaper,” as the press followed the pioneers on their trek out West.[11] The press (religious and popular) “swiftly became a sword of democracy, fueling ardent faith in the future of the American republic,” and decentralized religious authority. This effectually undermined the reverence for tradition, education, and station that previous generations displayed, and elevated populist leaders to positions once only held by (authorized) learned scholars.[12]

James Fenimore Cooper, author of the popular 1826 book, The Last Of The Mohicans, was the leader of the New York writing scene. In 1824 he created The Bread And Cheese Club, one of the oldest in the city, which included in its membership men from various professions. There was a young man from Massachusetts named William Cullen Bryant. In 1825 Bryant went to New York as editor of The New York Review and as of 1831, was the owner-editor of The New York Evening Post.[13] There was Gulian C. Verplanck, a lawyer of distinction who represented New York as a Democrat in the United States Congress.[14] (For a time he co-edited The Talisman with Bryant.)[15] It was in Verplanck’s home at Fishkill, on the Hudson, in May 1783, that The Society Of The Cincinnati was formed by the officers of the Continental Army, to “perpetuate the friendships which had been formed during the great struggle of the Revolutionary War, and to aid the unfortunate in the families of its members.” The name derived from Roman General, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, whom Washington was compared to, and served as the inspiration for Cincinnati, Ohio, when it was founded by a member of the group.[16] (Lord Byron, incidentally, would also compare Washington to Cincinnatus in his poem “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte,” writing: “Thou art the first, the last, the best. The Cincinnatus of the West.”)

Washington Irving, another member, was one of the first American authors to achieve global fame. In 1820 he published “The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow,” a story about a schoolmaster named Ichabod Crane who encounters a vengeful spirit known as the Headless Horseman in a village called Sleepy Hollow, a Dutch settlement about thirty miles north of Manhattan. Like many of his other works, it was attributed to his literary alter-ego, the fictional Dutch-American historian, Diedrich Knickerbocker. This pseudonym soon became an appellation for New Yorkers of old Dutch extraction, but was soon popularly applied as a nickname to anyone from New York City. Irving also directly bestowed the nickname “Gotham” for the city; originally appearing in his literary magazine Salmagundi in 1807, Irving playfully (and repeatedly) referred to Manhattan as the “ancient city of Gotham.” This was a nod to the medieval story of “The Merry Tales Of The Mad-Men Of Gotham.”[17] Irving’s name was threaded into the streets of “Gotham” the year that Greeley arrived in New York. In 1831, Samuel B. Ruggles purchased “Grammercy Seat” from the heirs of James Duane. Grammercy, from the Dutch “Crommessie,” was a tract of land four hundred feet on the Bowery Road that ran almost to the East River. Ruggles cut two wide streets through his property parallel with, and between, Third and Fourth Avenues. Being allowed by the City of New York to name the streets, Ruggles called one Irving Place, after his “admirable fellow-townsman” Washington Irving. He named the other street “with the just pride of a New England man,” Lexington Avenue, after the battlefield “where the first blood was shed for independence.”[18]

The first order of business for Greeley was to find a boardinghouse where he could live on a small sum of money. Strolling off into Broad Street, he discovered a house at the intersection of Wall Street that, in his eyes, had the aspect of a cheap tavern. Entering the barroom, he asked the barman for the price of board.

“I guess we’re too high for you,” said the barman after sizing-up the inquirer.

“Well, how much a week do you charge?”

“Six dollars.”

“Yes, that’s more than I can afford,” said Greeley with a laugh. He turned up Wall Street, sauntering onto Broadway.

A growing number of country boys and immigrant youths lived in all-male boardinghouses. America’s new urban centers with their disproportionate number of young, unmarried men, were becoming a problem. Cut off from family, friends, and churches of the rural towns they came from, it was feared they would inevitably slip into vice.[19] There was plenty of vice. Freed from constraints, these single men drank in saloons, visited brothels, and practiced “self-abuse.” That is, they practiced the “loathsome and beastly habit” of masturbation, which was said by the medical community to cause weakness, dyspepsia, impotency, and “masturbatory insanity.”[20] There were less debaucherous activities, too, however—for those who could afford it. There were a dozen first-class theatres, like The Park and The Bowery (the latter being the first playhouse in America with a stage lighted with gas.) Drama was the domain at The Olympic, and The National. The Franklin, one of the new theatres, was on Chatham Street, between James and Oliver. Vaudeville could be enjoyed at Niblo’s Garden as well as a circus at Vauxhall Garden. There was gambling on Chatham Row and on Sundays games in the Elysian Fields of Hoboken, New Jersey (duels on weekdays.) Picnics were held in the woods around Forty-Sixth Street; Horse Racing on upper Broadway, and rowing races on the Harlem River.[21] Greeley, however, could not afford such things, and seeing no house of entertainment that was at all suited to his circumstances, he wandered along the wharves of the North River as far as Washington Market. Here he found the “boarding-houses of the cheapest kind,” and “drinking-houses of the lowest grade.” The boardinghouses were frequented chiefly by immigrants; the drinkinghouses were favored by sailors who were numerous in that neighborhood. Women’s labor was the heart of this industry, for even when a man owned the house, boarding-housekeeping was women’s work. Transliterated to the marketplace, “housewifery” underwent a commercial transformation just as the notion of “home.”[22] Greeley spotted a small establishment that served as both a low groggery and cheap boardinghouse. It was kept by an Irishman named McGorlick. It looked so mean and squalid, that Greeley was tempted to enter and inquire for what sum a man could buy shelter and sustenance for a week.

“Twenty shillings,” McGorlick replied.

“Ah,” said Greeley, accepting the arrangement, “that sounds more like it.”

After settling into his room, Greeley bought some clothes to render himself more presentable. The garments were hardly fashionable, but the purchase absorbed nearly half his capital. Satisfied with his appearance, he made his rounds to the printing offices of the city, asking for employment. He went to every office he could find; merely asking, however, and leaving without a word as soon as he was refused. He found himself in the office of The Journal Of Commerce and spoke with David Hale, one of the proprietors of the paper.

“My opinion is, young man, that you’re a runaway apprentice, and you’d better go home to your master,” said Hale.

Greeley endeavored to explain his position and circumstances, but the impetuous proprietor could not be brought to a more gracious response.

“Be off about your business,” said Hale, “and don’t bother us.”

Greeley, more amused than indignant, retired and went along his way to the next office. The entire day he walked the streets, ten times as many miles as he needed. (He was not aware that all the printing offices in New York were practically in the same square mile.) He climbed into upper stories and came down again; he ascended other heights and descended those, too; he went into basements, slinked through passages, groped through labyrinths, asking everyone the same question: “Do you want a hand?” He was rejected each time in varying degrees of civility. He went home in the evening, very tired and discouraged. The next morning he continued his search with energy until the evening. Nobody wanted a hand. Business was at a standstill, or every office had its “full complement of men.” That evening he was still more fatigued. He decided to remain in the city a day or two longer and then if his job hunt was still unsuccessful, he would make his way back home, and inquire for work in the towns through which he passed. He was discouraged, not disheartened. On Sunday morning Greeley arose refreshed and cheerful. In the morning, he invited another boarder in the house to accompany him to a small Universalist Church on Grand Street (near Pitt Street and the Dry Dock.) The congregation that assembled in the diminutive chapel was led by Rev. Thomas J. Sawyer, who was still quite young. Greeley had never before heard a sermon that accorded with his own religious opinions.[23] In the afternoon he heard news that gave him hope that he might be able to remain in the city. An Irishman, a friend of McGorlick, came to pay his usual Sunday visit. He was a shoemaker who lived in a house that was often frequented by journeymen printers. He heard from them that hands were wanted at West’s Printing Office.

Greeley went to West’s, located at 85 Chatham Street, early on Monday morning. West’s printing office was on the second story; the ground floor was occupied by McElrath and Bangs, a bookstore. They were publishers and West was their printer. Neither store, nor office, was yet opened, so Greeley sat down on the steps to wait. It seemed very long before anyone came to work that morning. The steps on which Greeley sat were in the narrow part of Chatham Street, the gorge through which the “swarthy tide of mechanics” poured in the morning and evening. Thousands passed by, yet no one stopped until seven o’clock when one of West’s journeymen arrived. Finding the door still locked, the journeyman sat down on the steps next to Greeley. They fell into conversation, and Greeley stated his circumstances, something of his history, and his need for employment. This journeyman, a kind-hearted, intelligent man, also happened to be Vermonter and looked upon Greeley as a countryman. He was determined to help Greeley if he could. The doors were eventually opened, and the men began to arrive. Greeley and his new friend ascended to the office. The work of the day soon began. The foreman arrived, and the journeyman endeavored to interest him enough in Greeley to give him a trial. The work for which a man was wanted in the office was the composition of a Polyglot Testament. This was a version of The Bible with multiple translations of the text in parallel columns. It was, therefore, a kind of work that was extremely difficult and tedious. Several men had tried their hand at it only to give up in a few days. The foreman looked at Greeley. Greeley looked at the foreman. Partly to oblige the journeyman, and partly because he was unwilling to wound the feelings of the applicant by sending him abruptly away, the foreman consented to let him try.

“Fix up a case for him,” said the foreman, “and we’ll see if he can do anything.”

In a few minutes, Greeley was at work. After he had been at work an hour or two, Mr. West, the boss, arrived at the office.

“Did you hire that fool,” West asked the foreman with no small irritation.

“Yes; we must have hands, and he’s the best I could get,” said the foreman, justifying his conduct.

“Well,” said West, “for God’s sake pay him off tonight, and let him go about his business.”

Greeley worked through the day with his usual intensity and perfect silence. At night he presented to the foreman, as the custom then was, the “proof” of his day’s work. The foreman was astonished.

The proof before him was greater in quantity (and more correct) than that of any other day’s work that had yet been done on the Polyglot Testament.

There was no thought now of sending the new journeyman about his business. Greeley was an established man at once. From that point onward, for several months, Greeley worked regularly on the Testament with remarkable devotion and intensity, earning six dollars a week. While the young men and older apprentices roamed the streets seeking their pleasure, Greeley, by the light of a candle stuck in a bottle, eked out a slender day’s wages by setting up an extra column of the Polyglot Testament.[24]

SOURCES:

[1] Ellis, David Maldwyn. “The Yankee Invasion Of New York, 1783-1850.” New York History. Vol. XXXII, No. 1 (January 1951): 3-17.

[2] Tuchinsky, Adam-Max. “‘The Bourgeoisie Will Fall And Fall Forever’: The ‘New-York Tribune,’ The 1848 French Revolution, And American Social Democratic Discourse.” The Journal Of American History. Vol. XCII, No. 2 (September 2005): 470-497.

[3] Ellis, John B. Free Love And Its Votaries. A.L. Bancroft & Co. San Francisco, California. (1870): 29-31.

[4] Dixon, William Hepworth. Spiritual Wives: Vol. II. Hurst And Blackett, Publishers. London, England. (1868): 1-19.

[5] Bliss, Sylvester. Memoirs Of William Miller. Joshua V. Himes. Boston, Massachusetts. (1858): 98.

[6] Snay, Mitchell. “Horace Greeley’s New-Yorker: The Newspaper As Literary Institution In Jacksonian America.” New York History. Vol. XCII, No. 1/2 (Winter/Spring 2011): 41-51.

[7] Sumner, William Graham. Andrew Jackson As A Public Man. Houghton, Mifflin And Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1888): 99.

[8] Faherty, Duncan. “‘A Certain Unity Of Design’: Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Tales Of The Grotesque And Arabesque’ And The Terrors Of Jacksonian Democracy.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Vol. VI, No. 2 (Fall 2005): 4-21.

[9] Parton, J. The Life Of Horace Greeley. Mason Brothers. New York, New York. (1856): Frontispiece.

[10] Snay, Mitchell. “Horace Greeley’s New-Yorker: The Newspaper As Literary Institution In Jacksonian America.” New York History. Vol. XCII, No. 1/2 (Winter/Spring 2011): 41-51.

[11] Neu, J.L. “Rufus Wilmot Griswold.” University Of Texas Bulletin: Studies In English. No. 5 (October 8, 1925): 101-165.

[12] Mathews, Donald G. “The Second Great Awakening As An Organizing Process, 1780-1830: An Hypothesis.” American Quarterly. Vol. XXI, No. 1 (Spring 1969): 23-43; Conforti, Joseph. “The Invention Of The Great Awakening, 1795-1842.” Early American Literature. Vol. XXVI, No. 2 (1991): 99-118.

[13] O’Brien, Frank. The Story Of The Sun. George H. Doran Company. New York, New York. (1918): 121-124.

[14] Spann, Edward K. “Bryant And Verplanck, The Yankee And The Yorker, 1821-1870.” New York History. Vol. XLIX, No. 1 (January 1968): 11-28.

[15] “William Cullen Bryant.” The Aldine. Vol. II, No. 3 (March 1869): 20.

[16] Alderman, (Mrs.) L.A. The Identification Of The Society Of The Cincinnati With The First Authorized Settlement Of The Northwest Territory At Marietta, Ohio, April Seventh, 1788. E.R. Alderman & Sons. Marietta, Ohio. (1888): 4-26; “Society Of The Cincinnati.” The William And Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. Vol. IX, No. 3 (January 1901): 192-194.

[17] Burrows, Edwin G.; Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History Of New York City To 1898. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1998): xii-xiii.

[18] Pine, John B. The Story Of Gramercy Park, 1831-1921. Gramercy Park Association. New York, New York. (1921): 9-10.

[19] Cayton, Mary Kupiec. “The Making Of An American Prophet: Emerson, His Audiences, And The Rise Of The Culture Industry In Nineteenth-Century America.” The American Historical Review. Vol. XCII, No. 3 (June 1987): 597-620.

[20] Burrows, Edwin G.; Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History Of New York City To 1898. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1998): 533-534.

[21] O’Brien, Frank. The Story Of The Sun. George H. Doran Company. New York, New York. (1918): 121-124.

[22] Gamber, Wendy. “Tarnished Labor: The Home, The Market, And The Boardinghouse In Antebellum America.” Journal Of The Early Republic. Vol. XXII, No. 2 (Summer 2002): 177-204.

[23] Greeley, Horace. The Autobiography Of Horace Greeley. E.B. Treat. New York, New York. (1872): 70.

[24] Parton, J. The Life Of Horace Greeley. Mason Brothers. New York, New York. (1856): 118-122.