On January 29, 1845, ten days after Edgar Allan Poe’s thirty-sixth birthday, The Evening Mirror (New York) printed an advanced copy of his new poem, “The Raven.” “In our opinion, it is the most effective single example of ‘fugitive poetry’ ever published in this country,” the paper stated, “and unsurpassed in English poetry for subtle conception, masterly ingenuity of versification, and consistent, sustaining of imaginative lift and ‘pokerishness.’ It is one of these ‘dainties bred in a book’ which we feed on. It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it.”[1]

Edgar Allan Poe.[2]

Poe was born in Boston. “Perhaps it is just as well not to mention that we are heartily ashamed of the fact,” he would say. “The Bostonians are very well in their way. Their hotels are bad. Their pumpkin pies are delicious. Their poetry is not so good. Their common is no common thing—and the duck-pond might answer—if its answer could be heard for the frogs.” He adds: “But with all these good qualities the Bostonians have no soul […] The Bostonians are well-bred—as very dull persons very generally are.”[3] Poe did not consider himself a Northerner, and certainly not a child of the Puritans. “I am a Virginian—at least I call myself one,” he would say, “for I have resided all my life, until within the last few years, in Richmond.” John Poe, the progenitor of the family in America, immigrated from Ireland some years before the American Revolution.)[4] As James Russell Lowell stated in his biography of Poe in the February 1845 issue of Graham’s Magazine:

Remarkable experiences are usually confined to the inner life of imaginative men, but Mr. Poe’s biography displays a vicissitude and peculiarity of such as is rarely met with. The offspring of a romantic marriage, and left an orphan at an early age, he was adopted by Mr. Allan, a wealthy Virginian whose barren marriage-bed seemed the warranty of a large estate to the young poet. Having received a classical education in England, he returned home and entered the University of Virginia, where, after an extravagant course, followed by reformation at last extremity, he was graduated with the honors of his class […] He now the military academy at West Point, from which he obtained a dismissal on hearing of the birth of a son to his adopted father, by a second marriage, an event which cut off his expectations as an heir. The death of Mr. Allan, in whose will his name was not mentioned, soon after relieved him of all doubt in this regard, and he committed himself at once to authorship for support. Previously to this, however, he had published (in 1827) a small volume of poems [Tamerlane And Other Poems,] which soon ran through three editions, and excited high expectations of its author’s future distinction in the minds of many competent judges. [5]

A synopsis of the rest of his life, from that point until 1845, is as follows. In 1829 Poe published Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems. The titular “Al Aaraaf,” inspired by (A’raf in the Qur’an) was, according to Poe: “A tale of another world—the star discovered by Tycho Brahe, which appeared and disappeared so suddenly—or rather, it is no tale at all.” The critics hated it.[6] Poe then went to Baltimore where he stayed with his widowed aunt, Maria Clemm, and her daughter, Virginia. November 29, 1829, was a memorable day in the annals of Baltimore, commemorating, as it did, the crowning of the first monument to Washington (a work that commenced in 1815, on the Fourth of July.)[7] Poe re-matriculated at West Point but left again for Baltimore after purposely getting himself court-martialed. He turned to prose and was published in some journals in Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Washington Monument. Baltimore, Maryland.[8]

A wealthy Baltimorean introduced Poe to Thomas W. White, the editor of Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger. By 1835, Poe was assistant editor of said paper. White, however, soon fired him for drunkenness on the job. Poe returned to Baltimore that year and married his cousin, Virginia. Re-instated by White in 1837, Poe, Virginia, and Maria Clemm, relocated to Richmond. Poe was embittered by the lack of recognition (and a living wage) he thought he deserved; a resentment which fermented when he reflected on the success of his New England contemporaries. In his mind, they produced inferior literary works, yet they reaped prestige, accolades, and liberal monetary rewards, “New Englanders knew me least and are my enemies,” he would say.[9] He wanted to expose the inner workings of the Northern-dominated literary establishment and the publishing industry it operated. At the same time, he sought to elevate Southern writers and give their voices a larger platform.[10]

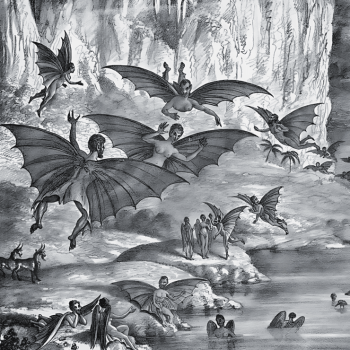

Poe and his family returned to the North in 1838 to live in Philadelphia. Poe at the time wrote his only novel, The Narrative Of Arthur Gordon Pym Of Nantucket. In 1839 he was editor of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, work which elevated his reputation as a literary critic. 1839 saw the release of his Tales Of The Grotesque And Arabesque. “My friends would be quite as wise in taxing an astronomer with too much astronomy, or an ethical author’ with treating too largely of morals,” Poe stated in the preface. “The truth is that, with a single exception, there is no one of these stories in which the scholar should recognize the distinctive features of that species of pseudo-horror which we are taught to call Germanic […] If in many of my productions terror has been the thesis, I maintain that terror is not of Germany, but of the soul.”[11] The twenty-five tales in the collection, written throughout the 1830s, were a study of horrors beneath the surface of Jacksonian America. Stories like “The Fall Of The House Of Usher,” ruminate on the instability of the time; of lost identity, a house in ruins, and failed relationships. Others, like “King Pest,” being a reflection of disease (especially in light of the cholera outbreak of the early 1830s.)[12]

Poe left Burton’s in 1841 to accept a position as co-editor at Graham’s Magazine, a publication in which he also wrote a number of articles. It was in Graham’s that he published the first modern detective story in April 1841, “Murders In The Rue Morgue.”[13] (A “sequel” was published a few months later, “The Mystery Of Marie Roget,” in The Ladies’ Companion.[14] It was inspired by the real 1841 case of Mary Cecilia Rogers, a twenty-year-old woman whose corpse was found floating in the Hudson in 1841.)[15] He began his “Longfellow War” at this time. His opponent, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was a Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard, but Poe referred to him as the “Professor of Moral Philosophy.”[16] Poe could not stomach the Transcendentalists, or the “Frogpondians” as he called them. The “burlesque philosophy, which the Bostonians have adopted” only fortified his low-opinion of the New England literati. Poe knew very well there “existed a predetermination” among a “certain clique” of Frogpondians that desired to sling their abuses at him “under any circumstances.” He knew that no matter what he wrote, they would “swear it to be worthless.” Even if he composed for them a “Paradise Lost,” they would declare it an “indifferent poem.” He knew it was pointless putting himself through the trouble of “attempting to please these people.”[17] Poe maintained that it was not all Transcendentalists that he disliked, “only the pretenders and sophists among them.”[18] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller, were, judging from his writings, presumably not among the Transcendentalists he favored. He poked jabs at The Dial, the journal established in 1840 by the Transcendentalists, and (indirectly) its editor, Fuller.[19] As for Emerson, he belonged “to a class of gentlemen with whom [Poe had] no patience whatever—the mystics for mysticism’s sake.”[20]

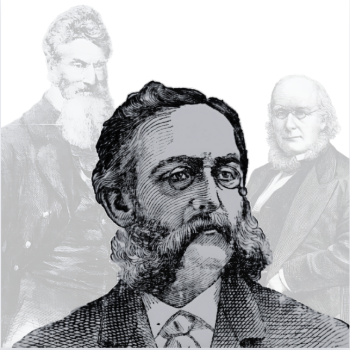

It was at this time that Poe met Rufus Wilmot Griswold; a journalist and critic from Rutland, Vermont, Griswold was living in Philadelphia at the time working on an anthology titled The Poets And Poetry In America. The manager of a country newspaper for many years, he entered the larger field of metropolitan journalism in 1839 when Horace Greeley (owner of The New-York Tribune) secured a position for him at The Daily Whig.[21] Poe left Graham’s in 1842 and returned to New York, working briefly at The Evening Mirror and later becoming editor (and later owner) of The Broadway Journal. Griswold, meanwhile, succeeded Poe as editor of Graham’s.[22] At the same time, Griswold released The Poets And Poetry In America. A few of Poe’s writings were included in the anthology, they were greatly outnumbered by the contributions of his Northern rivals. Poe felt slighted, not just for himself, but for all Southern writers. Though his review of Griswold’s book was generally positive, he remarked on the lack of representation. “Perhaps the author, without being aware of it himself, has unduly favored the writers of New England,” Poe stated. “The editor has scarcely done justice to some of our younger poets, either in his estimate of their genius or in his selections from their poems.” William Gilmore Simms, editor of Magnolia (a Southern monthly journal,) echoed Poe’s sentiment. “The book is a collection of the poetry chiefly of the Northern states, while the South is almost wholly overlooked by him,” Simms declared. “We protest against this injustice. The Southern states will be degraded in the eyes of the foreigners, by the course, which this partial and prejudiced compiler had pursued.”[23] For the next few years, the relationship between Poe and Griswold was a pit with a pendulum swinging from hostility to coolness.

Returning to 1845, about a month after the publication of “The Raven,” Poe was set to deliver a lecture at New York’s Society Library on February 28, 1845. The day was an emotional one for the nation, as the Republic of Texas was annexed by the United States. During the decade of its independence, it had been a source of anxiety between the North and South, arousing hostile sectional controversy. Abolitionists, determined to prevent the further spread of slavery, claimed that annexation would be unconstitutional and cause the dissolution of the Union (intimating that such an act would justify the secession of non-slave States.) The Southern States, for their part, declared that by refusing to annex Texas, it would justify their secession from the Union.[24] Perhaps this tension between Northerners and Southerners was present that evening. There was clearly something on Poe’s mind besides poetry when he delivered his lecture. “Mr. Poe,” The Tribune stated, “indulged in considerable small smartness on the character of our average criticism, and still more pointedly with reference to the Transcendentalists, so styled, whom he assailed with a coarse vulgarity quite out of place in such a Lecture.”[25] (He even accused Longfellow of plagiarism.)[26] In an effort to bury the hatchet with Griswold, however, Poe omitted anything in his talk that might have been offensive to him.[27]

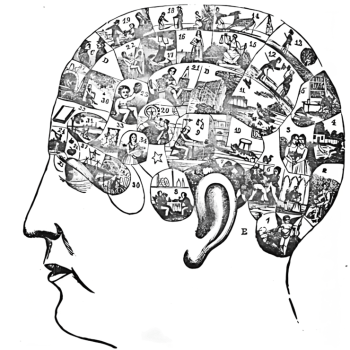

Poe was no doubt aware that Margaret Fuller had, a few weeks earlier, moved to New York to begin work for Greeley at The Tribune.[28] His feelings about the Transcendentalist had not changed. He regarded the “Brook Farm Phalanx” as “Crazyites.”[29] Brook Farm, the experimental Transcendentalist commune in Roxbury, Massachusetts, began in 1840 through the efforts of the Unitarian Minister, George Ripley and his wife, Sophia.[30] (A fictionalized Brook Farm is depicted in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1852 romance, The Blithedale Romance.)[31] In 1844, the community styled itself the “Brook Farm Phalanx” in accordance with the teachings of Charles Fourier.[32] This change came about with the reforms of Albert Brisbane, a devotee of Fourier.[33] Fuller, however, a frequent guest of the Brook Farm commune, was a fair critic of Poe (if somewhat harsh on the “accidentals” of his writing.)[34] When Albert Brisbane and the Brook Farm Phalanx began publishing their journal, The Harbinger, in June 1845, Poe mocked the “Snook Farm Phalanx” without remorse.[35] Nevertheless, when Fuller reviewed Poe’s Tales in July 1845, she did so with praise for the author, but added: “Several of his stories make us wish he would enter the higher walk of the metaphysical novel,” writes Fuller.[36] The “Murders In The Rue Morgue” made a particularly favorable impression on her. It so happened that phrenology, which is mentioned in the very first line of that story, was a topic that Poe would address a few weeks after Fuller’s review was published.[37] There was a misunderstanding, it seemed, in The American Phrenological Journal And Miscellany.

He knew the proprietors of the journal, the Fowler brothers, Orson and Lorenzo, as their paths overlapped in both Philadelphia and New York. Orson Fowler was the first of the brothers to become interested in phrenology; he began his career in that field while a student at Amherst in the early 1830s. By the middle of that decade, both brothers were lecturing around the country. In 1838 they established an office in Philadelphia called the Phrenological Museum and, soon after, the Phrenological Rooms on Broadway in Manhattan. The brothers subsequently established the Fowler & Wells Phrenological Cabinet with their brother-in-law, Samuel Wells. (Wells was married to their sister, Charlotte Fowler.) The place “might have been called Golgotha,” it was said, for “it was literally a place of skulls.” These skulls “with plaster busts, carefully mapped out on the surface to show the topography within” were prominently displayed in the window case.[38] Walt Whitman, still a young poet, was a frequent visitor. “One of the choice places of New York to me then was the ‘Phrenological Cabinet’ of Fowler & Wells, Nassau Street near Beekman,” Whitman writes. “Here were all the busts, examples, curios and books of that study obtainable.”[39] The literary organ of Fowler & Wells, The American Phrenological Journal, was published in lower Manhattan.[40] Through this, they quickly became the “recognized leaders in phrenological science, physiological, and hygienic sciences,” and the first in America to give the science of phrenology a practical value by making special delineations of character.[41] They had attracted many advocates, like Greeley, from the ranks of social reformers. (Their racial theories regarding “craniology,” however, are antiquated to say the least.)[42] In September 1845 Fowler & Wells published Poe’s “Mesmeric Revelation,” not realizing it was a satirical piece.[43] Poe told the phrenologists the same thing he told George Bush (Professor of Hebrew at New York University,) it was “purely fiction” that had ”some thoughts which are original.”[44]

A month later, on October 16, 1845, Poe delivered a lecture at the Boston Lyceum. (Arrangements for which he was assisted by James Russell Lowell.) The appointment for said lecture was under the supposition that Poe would read an original poem. There was much curiosity to see him in Boston, for his prose writings had been eagerly read by the denizens of “New Athens” (at least among college students.) His poems, likewise, were beginning to excite attention. Caleb Cushing introduced Poe with a solid (and very partisan) address.[45] Cushing had just returned from his mission to China where, a year earlier, he strong-armed the Imperial Government into the Treaty of Wanghia. This was in the wake of the Opium War and the (British-Chinese) Treaty Of Nanking. This result would be the rapid growth in trade between America and China, as well the export of Protestant Missionaries (of which America had in surplus.)[46]

After he was introduced, Poe stood “with a sort of shrinking” before the audience. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a theology student at the Harvard Divinity School who was present, later said: “I distinctly recall his face, with its ample forehead, brilliant eyes, and narrowness of nose and chin; an essentially ideal face, not noble, yet anything but coarse; with the look of over-sensitiveness which when uncontrolled may prove more debasing than coarseness.” Poe began by apologizing for his poem in a “hardly musical voice” and a deprecation of the criticism that he expected to receive from a Boston audience. With thin and tremulous tones, he reiterated this point “in a sort of persistent, querulous way,” that did not seem like satire. As Higginson recalled: “[It] impressed me at the time as nauseous flattery.” Only then did he abruptly begin the recitation of his “rather perplexing poem.” The audience looked positively mystified. He was not reciting an original poem, nor was he reciting “The Raven.” Rather, Poe was reciting one of his oldest poems, “Al Aaraaf,” which had been panned by critics in 1829. In truth, the words did not produce any distinct impression on the audience until Poe began to read the maiden’s song in the second part. His tones, now softened to a finer melody, arrived at the verse:

“Ligeia! Ligeia,

My beautiful one!

Whose harshest idea

Will to melody run,

O! is it thy will

On the breezes to toss?

Or capriciously still

Like the lone albatross

Incumbent on night

(As she on the air)

To keep watch with delight

On the harmony there?”

“His voice seemed attenuated to the finest golden thread,” Higginson states. “The audience became hushed, and, as it were, breathless; there seemed no life in the hall but his; and every syllable was accentuated with such delicacy, and sustained with such sweetness as I never heard equaled by other lips. When the lyric ended, it was like the ceasing of the gipsy’s chant in Browning’s ‘Flight Of The Duchess.’”

Higginson remembered nothing more, except that, when walking back to Cambridge, he and his comrades felt that they “had been under the spell of some wizard.”[47]

Cornelia Wells Walter, editor of the Daily Evening Transcript (Boston,) stated: “The anniversary exercises before the Boston Lyceum last evening were heavy and uninteresting, and illy adapted to an introductory to a course of lectures.”[48] This was a “sad tale invented to suit her own purposes,” Poe said in response. “We shall never call a woman ‘a pretty little witch’ again, as long as we live.”[49] Then Brisbane’s Harbinger chimed in: “Mr. Poe has earned some fame by various tales and poems, which of late has become notoriety through a certain black guard warfare which he has been waging against the poets and newspaper critics of New England, and which it would be most charitable to impute to insanity,” it stated. “He seems to think that the whole literary South and West are doing anxious battle in his person against the old time-honored tyrant of the North.” It further stated that Poe was more concerned with “insulting a Boston audience, inditing coarse editorials against respectable editresses, and getting singed himself,” than being a poet.[50] Poe, in turn, replied:

There is something in all this which we really respect—an evident wish to be sincere, pervading the whole time of the sermon—at least as far as convenient. The Brook Farm Phalanx talks to us, in short, “like a Dutch uncle,” and we shall reply to it, very succinctly, in the same spirit. “Very charitable to impute to insanity.” Insanity is a word that the Brook Farm Phalanx should never be brought to mention under any circumstances whatsoever […] “Insulting a Boston audience”—very true—meant to di it—and did.[51]

It was not long after this that Poe and George Bush attended a lecture delivered by the “Poughkeepsie Seer,” Andrew Jackson Davis. The presence of Poe conveyed to the Medium a feeling akin to a beautiful field or blooming valley, surrounded by a wall of mountains—mountains so high that the sun could barely shine over their summits. There was something unnatural about Poe’s voice, he noticed. Something, likewise, dispossessing in his manners. It seemed to Davis as though, in spirit, Poe was a foreigner—a man with conflicting breathings of commanding power in his mind. When Poe walked in through the hall (and again when he left,) Davis saw a perfect shadow of Poe in the air in front of him, as though the sun was constantly shining behind the writer, and casting shadows before him. It caused the singular appearance of one who ventured forth into a dark fog that he, himself, produced.[52]

SOURCES:

[1] “Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Raven.” The Evening Mirror. (New York, New York) January 29, 1845.

[2] Lowell, James Russell. “Our Contributors: Edgar Allan Poe.” Graham’s Magazine. Vol. XXVI, No. 2 (February 1845): 49-53.

[3] Poe, Edgar Allan. “Editorial Miscellany.” The Broadway Journal. Vol. II, No. 17 (November 1, 1845): 261-262.

[4] Harrison, James A. Life Of Edgar Allan Poe. Thomas Y. Cromwell Publishers. New York, New York. (1903): 2-4.

[5] Lowell, James Russell. “Our Contributors: Edgar Allan Poe.” Graham’s Magazine. Vol. XXVI, No. 2 (February 1845): 49-53.

[6] Harrison, James A. Life Of Edgar Allan Poe. Thomas Y. Cromwell Publishers. New York, New York. (1903): 75-76.

[7] Washington Monument. Washington Monument, Baltimore. Account Of Laying The Corner Stone, Raising The Statue, Description, &c. &c. Washington Monument. Baltimore, Maryland. (1849): 31.

[8] Ibid: Frontispiece.

[9] Carlson, Eric W. “Poe’s Ten-Year Frogpondian War.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Vol. III, No. 2 (Fall 2002): 37-51.

[10] Prown, Katherine Hemple. “The Cavalier And The Syren: Edgar Allan Poe, Cornelia Wells Walter, And The Boston Lyceum Incident.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. LXVI, No. 1 (March 1993): 110-123.

[11] Poe, Edgar Allan. Tales Of The Grotesque And Arabesque: Vol I. Lea And Blanchard. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1840): Preface.

[12] Faherty, Duncan. “‘A Certain Unity Of Design’: Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Tales Of The Grotesque And Arabesque’ And The Terrors Of Jacksonian Democracy.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Vol. VI, No. 2 (Fall 2005): 4-21.

[13] Poe, Edgar Allan. “Murders In The Rue Morgue.” Graham’s Magazine. Vol. XVIII, No. 4 (April 1841): 166-178.

[14] Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Mystery Of Marie Roget.” The Ladies’ Companion. Vol. XVIII, No. 1 (November 1842): 15-20; Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Mystery Of Marie Roget.” The Ladies’ Companion. Vol. XVIII, No. 2 (December 1842): 93-99; Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Mystery Of Marie Roget.” The Ladies’ Companion. Vol. XVIII, No. 4 (February 1843): 162-167.

[15] “Examination In The Case Of Miss Rogers.” The Evening Post. (New York, New York) August 13, 1841.

[16] Prown, Katherine Hemple. “The Cavalier And The Syren: Edgar Allan Poe, Cornelia Wells Walter, And The Boston Lyceum Incident.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. LXVI, No. 1 (March 1993): 110-123.

[17] Poe, Edgar Allan. “Editorial Miscellany.” The Broadway Journal. Vol. II, No. 20 (November 22, 1845): 309-311.

[18] Carlson, Eric W. “Poe’s Ten-Year Frogpondian War.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Vol. III, No. 2 (Fall 2002): 37-51.

[19] In “Never Bet Your Head,” Poe writes: “It has been proved that no man can sit down to write without a very profound design. Thus to authors in general much trouble is spared. A novelist, for example, need have no care of his moral. It is there—that is to say it is somewhere—and the moral and the critics can take care of themselves. When the proper time arrives, all that the gentleman intended, and all that he did not intend, will be brought to light in the ‘Dial.’” [Poe, Edgar Allan. “Never Bet Your Head.” Graham’s Magazine. Vol. XIX, No. 3 (September 1841): 124-127.]

[20] Poe, Edgar Allan. “An Appendix Of Autographs.” Graham’s Magazine. Vol. XX, No. 1 (January 1842): 44-49.

[21] Neu, J.L. “Rufus Wilmot Griswold.” University Of Texas Bulletin: Studies In English. No. 5 (October 8, 1925): 101-165.

[22] Campbell, Killis. “The Poe-Griswold Controversy.” PMLA. Vol. XXXIV, No. 3 (1919): 436-464.

[23] Neu, J.L. “Rufus Wilmot Griswold.” University Of Texas Bulletin: Studies In English. No. 5 (October 8, 1925): 101-165.

[24] Barker, Eugene C. “The Annexation Of Texas.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Vol. L, No. 1 (July 1946): 49-74.

[25] “Edgar A. Poe.” The New-York Tribune. (New York, New York) March 1, 1845.

[26] Prown, Katherine Hemple. “The Cavalier And The Syren: Edgar Allan Poe, Cornelia Wells Walter, And The Boston Lyceum Incident.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. LXVI, No. 1 (March 1993): 110-123.

[27] Campbell, Killis. “The Poe-Griswold Controversy.” PMLA. Vol. XXXIV, No. 3 (1919): 436-464.

[28] Carlson, Eric W. “Poe’s Ten-Year Frogpondian War.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Vol. III, No. 2 (Fall 2002): 37-51.

[29] Poe, Edgar Allan. “Editorial Miscellany.” The Broadway Journal. Vol. II, No. 23 (December 13, 1845): 309-311.

[30] Noyes, John Humphrey. History Of American Socialism. J.B. Lippincott & Co. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1870): 102-118.

[31] Hawthorne writes: “Often, however, in these years that are darkening around me, I remember our beautiful scheme of a noble and unselfish life; and how fair, in that first summer, appeared the prospect that it might endure for generations, and be perfected, as the ages rolled away, into the system of a people and a world!” [Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Blithedale Romance: Vol. II. Chapman And Hall. London, England. (1852): 282.] In his biography of Hawthorne, Henry James, Jr. writes: “It seems odd, as his biographer says, ‘that the least gregarious of men should have been drawn into a socialistic community;’ but although it is apparent that Hawthorne went to Brook Farm without any great Transcendental fervour, yet he had various good reasons for casting his lot in this would-be happy family. He was as yet unable to marry, but he naturally wished to do so as speedily as possible, and there was a prospect that Brook Farm would prove an economical residence. And then it is only fair to believe that Hawthorne was interested in the experiment, and that though he was not a Transcendentalist, an Abolitionist, or a Fourierite, as his companions were in some degree or other likely to be, he was willing, as a generous and unoccupied young man, to lend a hand in any reasonable scheme for helping people to live together on better terms than the common. The Brook Farm scheme was, as such things go, a reasonable one; it was devised and carried out by shrewd and sober-minded New Englanders, who were careful to place economy first and idealism afterwards, and who were not afflicted with a Gallic passion for completeness of theory. There were no formulas, doctrines, dogmas; there was no interference whatever with private life or individual habits, and not the faintest adumbration of a rearrangement of that difficult business known as the relations of the sexes. The relations of the sexes were neither more nor less than what they usually are in American life, excellent; and in such particulars the scheme was thoroughly conservative and irreproachable. Its main characteristic was that each individual concerned in it should do a part of the work necessary for keeping the whole machine going. He could choose his work and he could live as he liked; it was hoped, but it was by no means demanded, that he would make himself agreeable, like a gentleman invited to a dinner-party. Allowing, however, for everything that was a concession to worldly traditions and to the laxity of man’s nature, there must have been in the enterprise a good deal of a certain freshness and purity of spirit, of a certain noble credulity and faith in the perfectibility of man, which it would have been easier to find in Boston in the year 1840, than in London five-and-thirty years later. If that was the era of Transcendentalism, Transcendentalism could only have sprouted in the soil peculiar to the general locality of which I speak–the soil of the old New England morality, gently raked and refreshed by an imported culture. The Transcendentalists read a great deal of French and German, made themselves intimate with George Sand and Goethe, and many other writers; but the strong and deep New England conscience accompanied them on all their intellectual excursions, and there never was a so-called ‘movement’ that embodied itself, on the whole, in fewer eccentricities of conduct, or that borrowed a smaller license in private deportment. Henry Thoreau, a delightful writer, went to live in the woods; but Henry Thoreau was essentially a sylvan personage and would not have been, however the fashion of his time might have turned, a man about town. The brothers and sisters at Brook Farm ploughed the fields and milked the cows; but I think that an observer from another clime and society would have been much more struck with their spirit of conformity than with their déréglements. Their ardour was a moral ardour, and the lightest breath of scandal never rested upon them, or upon any phase of Transcendentalism.” [James, Jr., Henry. Hawthorne. MacMillan And Co. London, England. (1879): 82-83.]

[32] The French Utopian-Socialist, Charles Fourier, called for the equality of women and condemned their position of servitude in the marriage institution. The Fourierists believed in a utopian society of the future. Fourier envisioned this utopian society (which he called “Harmony”) as a commune that was organized into “Phalanxes” of about 2000 people. An early proponent of universal basic income, Fourier’s comprehensive (and ambitious) plan took into consideration the many facets of the social organism, and was confident that he could alleviate social ills like poverty. [Leopold, David. “Education And Utopia: Robert Owen And Charles Fourier.” Oxford Review Of Education. Vol. XXXVII, No. 5 (October 2011): 619-635.]

[33] Guarneri, Carl J. “Importing Fourierism To America.” Journal Of The History Of Ideas. Vol. XLIII, No. 4 (October-December 1982): 581-594.

[34] Kopacz, Paula. “Feminist At The ‘Tribune’: Margaret Fuller As Professional Writer.” Studies In The American Renaissance. (1991): 119–139.

[35] “The Harbinger.” The Harbinger. Vol. I, No. 1 (June 14, 1845): 16; Poe, Edgar Allan. “Editorial Miscellany.” The Broadway Journal. Vol. II, No. 23 (December 13, 1845): 309-311.

[36] Fuller, Margaret. “Tales: By Edgar A. Poe.” The New-York Tribune. (New York, New York) July 11, 1845; Carlson, Eric W. “Poe’s Ten-Year Frogpondian War.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review. Vol. III, No. 2 (Fall 2002): 37-51.

[37] “It is not improbable that a few farther steps in phrenological science will lead to a belief in the existence, if not to the actual discovery and location of an organ of analysis.” [Poe, Edgar Allan. “Murders In The Rue Morgue.” Graham’s Magazine. Vol. XVIII, No. 4 (April 1841): 166-178.]

[38] Barrows, Isabel Chapin. A Sunny Life: The Biography Of Samuel June Barrows. Little, Brown & Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1913): 53-54.

[39] [Whitman, Walt. Good-Bye My Fancy: 2d Annex To Leaves Of Grass. David McKay. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1891): 57.] Fowler & Wells moved to 308 Broadway in 1854. [“Alcohol And The Constitution Of Man.” The Westerly Echo & Pawcatuck Advertiser. (Westerly, Rhode Island) April 6, 1854.]

[40] Mackey, Nathaniel. “Phrenological Whitman.” Conjunctions. No. 29 (Fall 1997): 231-251.

[41] King, Moses. King’s Handbook Of New York City: An Outline History And Description Of The American Metropolis. Moses King. New York, New York. (1892): 291-292.

[42] “African mentality will undoubtedly descend from sire to son,” Orson Fowler writes, “throughout all their generations, till this race, like the Indian, yields its place to those naturally superior.” [Fowler, Orson Squire. Hereditary Descent: Its Laws And Facts Applied To Human Improvement. Fowlers & Wells. New York, New York. (1848): 135.]

[43] “Whatever doubt may still envelop the rationale of mesmerism, its startling facts are now almost universally admitted. Of these latter, those who doubt are your mere doubters by profession—an unprofitable and disreputable tribe. There can be no more absolute waste of time than the attempt to prove, at the present day, that man, by mere exercise of will, can so impress his fellow as to cast him into an abnormal condition, whose phenomena resemble very closely those of death, or at least resemble them more nearly than they do the phenomena of any other normal condition within our cognizance; that, while in this state, the person so impressed employs only with effort, and then feebly, the external organs of sense; yet perceives, with keenly refined perception, and through channels supposed unknown, matters beyond the scope of the physical organs; that moreover, his intellectual faculties are wonderfully exalted and invigorated; that his sympathies with the person so impressing him are profound; and finally, that his susceptibility to the impression increases with its frequency, while in the same proportion, the peculiar phenomena elicited are more extended and more pronounced.” In: [“Article IV: Magnetic Developments.” The American Phrenological Journal. Vol. VII, No. 9 (September 1845): 304-311.]

[44] Stern, Madeleine B. “Poe: ‘The Mental Temperament’ For Phrenologists.” American Literature. Vol. XL, No. 2 (May 1968): 155-163.

[45] “Mr. Cushing’s address was one long laudation upon America at the expense of Great Britain — a composition that seemed written rather for popular effect, than for the influence of sound judgment or the development of that high moral tone which should ever characterize all public exercises having form their theme any subject of national importance.” [Walter, Cornelia Wells. “A Failure.” Daily Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) October 17, 1845.]

[46] Kuo, Ping Chia. “Caleb Cushing And The Treaty Of Wanghia, 1844.” The Journal Of Modern History. Vol. V, No. 1 (March 1933): 34–54.

[47] Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Short Studies Of American Authors: II—Poe.” Literary World. Vol. X, No. 6 (March 15, 1879): 89-90.

[48] Walter, Cornelia Wells. “A Failure.” Daily Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) October 17, 1845.

[49] Poe, Edgar Allan. “Editorial Miscellany.” The Broadway Journal. Vol. II, No. 17 (November 1, 1845): 261-262.

[50] “Review: The Raven And Other Poems.” The Harbinger. Vol. I, No. 26 (December 6, 1845): 410-411.

[51] Poe, Edgar Allan. “Editorial Miscellany.” The Broadway Journal. Vol. II, No. 23 (December 13, 1845): 309-311.

[52] Davis, Andrew Jackson. Memoranda Of Persons, Places, And Events. William White & Company. New York, New York. (1868): 18-19.