In the last days of September 1859, Henry Steel Olcott, Associate Agricultural Editor of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, was in St. Louis, Missouri, covering a conference held by the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad Company. During one of the noon recesses, Olcott and other members of the Press, were invited to Pomological Hall for a wine tasting by D. Nicholson (the celebrated grocer on Market Street.) They were soon joined by Robert Marcellus Stewart. Elected as the Governor of Missouri in 1857, his tenure coincided with the escalating border skirmishes which Greeley named “Bleeding Kansas” in 1856.[1]

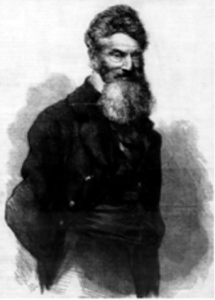

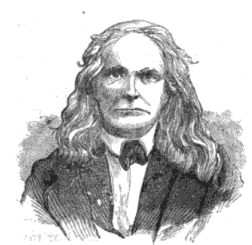

John Brown.[2]

As the name suggests, these conflicts developed at the borders of Missouri and the Kansas Territory. The immediate cause was the political and ideological debate of whether or not slavery would be permitted in the proposed state of Kansas. When Kansas joined the Union, it would gain two new senators whose stance on slavery would affect the already precarious balance of power. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 called for popular sovereignty, meaning the decision about slavery would be put to a popular vote by the settlers of the territory instead of legislators in Washington, D.C. The combatants in these scrimmages were the pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” and the anti-slavery “Free-Staters.”[3] The former arrived in the thousands in 1854 to sway the election. The Abolitionists of the latter group followed a similar plan, many finding financial support with the New England Emigrant Aid Company.[4] The most famous Free-Stater, by far, was a fifty-nine-year-old Ohioan named John Brown. Like Olcott, Brown was of old Puritan stock, his ancestor being Peter Brown who came over on the Mayflower.[5] (The progenitor of the Olcott line in America, Thomas Olcott, arrived ten years after the Mayflower landed.)[6] A devoutly religious man, Brown spoke often of his “great destiny.” Hearing this, many of his friends and relatives thought him genuinely insane. A peculiar and unpredictable man, indeed; even his seven sons, were intimidated by him (though they would go to hell and back at the old man’s word.)[7]

“Gentlemen of the Press—from every portion, I believe, of the Union—I consider myself highly honored in being called upon,” said Governor Stewart. “As the Executive of the State of Missouri, I am glad to see so many intelligent gentlemen from different portions of the Union, who, perhaps, may have heretofore misunderstood the resources of the State which I have the honor to represent as chief executive. I trust they will find the people of Missouri are actuated by every generous and noble impulse, which from a long experience with them, I am ready to declare them possessed of. I am extremely gratified that we have met here today in this vast amphitheater—the far-west in one sense—and on the other hand, the center of the American Continent. (Cheers.) It is, if I may so speak, the hub of the American Continent, into which all the spokes of the whole country are entered,” Governor Stewart continued amidst more cheers. “Permit me to say, in connection, that we are not altogether Border Ruffians—as I myself supposed some of the people of Missouri were before I came here. (Laughter.) I remember that when I first came to this State I was suspected of being a Mormon. (Great laughter.) Gentlemen, I came from New York, the old Empire State of the East, to Missouri, the new Empire State of the West, and what will soon become the real Empire State of the great American Republic. For my part, I like the East, for there my father lived—there my mother still lives—and every association connected therewith is dear, but still I love the Valley of the Mississippi. I love Missouri as the State of my adoption and I love the Union better than all the world.” (Great cheering.)

Loud calls were then made for Olcott to speak.

“I suppose, gentlemen, you wish me to respond to His Excellency, the Governor, for the kind sentiments he has expressed to the members of the Press, and I am sure we all unite, individually and collectively, in reciprocating the kindly feeling which he has expressed,” said Olcott. “I rejoice to see such an assemblage as I witness on this occasion. I think it is not saying too much when I declare that I believe this exhibition exceeds anything which has ever taken place in this country. I have had the pleasure of attending English Fairs, which, in some respects, are superior to ours, but I am confident that your show of stock cannot be excelled, and as for the beauty of the grounds and the strictures, they are decidedly superior to anything I have ever seen, either in this country or England.” Olcott turned to address Governor Stewart. “And now, sir, as you are the representative of the Border Ruffian spirit, so-called, and I the representative of a so-called Abolition sheet, I am ready to bury the hatchet of animosity, and extend to you the right hand of fellowship.”[8]

~

Olcott was born in 1832 in Orange, New Jersey, he was the seventh generation of “Puritan stock,” his parents being Thomas Olcott and Emily Steel. Politically he was what one called “a congenital Whig.” That is, his family were supporters of the Whig Party. [9] Emerging in the 1830s in opposition to Democrat President, Andrew Jackson, the Whig Party was comprised largely of former members of the National Republican Party, the Anti-Masonic Party, and disaffected Democrats. The party, it was said, “was in many respects of the representative of the old Federal party.”[10] Their base of support was (evangelical) Protestants, entrepreneurs, and the cosmopolitan middle class. When he was fifteen, Olcott enrolled in New York University, but financial strain compelled him to drop out. He left home for Ohio in 1848 to try his hand at share-farming.

That year nearly every nation across Europe experienced a Revolution, challenging the existing order. (This is when Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto.)[11] In America, the Mexican-American War, which began in 1846, was coming to an end. John L. O’Sullivan of the “Young America Movement” coined the phrase “Manifest Destiny” (referencing the annexation of Texas.)[12] It was also the same year that the Fox Sisters heard the disembodied spirit “rappings” in their home in Rochester, New York, thereby giving rise to the movement known as Spiritualism. Olcott and his boss, Horace Greeley (A man who Olcott considered a dear friend,) came to the Spiritualist movement just about the same time in the summer of 1850. The Fox sisters, at that time, were in New York, staying as guests in Greeley’s home. The feats they displayed during their séances became the source of a public discussion that raged around the subject. The poet William Cullen Bryant and James Fenimore Cooper, the author of The Last Of The Mohicans (1826) attended a memorable séance together at this time.[13] (It was said that sometime after attending the séance with the Fox sisters, when Fenimore Cooper came to believe in Spiritualism and his interest in “magnetic trances” was connected with the occult.)[14] Just weeks after this séance, the Fox sisters went to Cleveland, Ohio, where they likewise confounded and amazed the citizens of the “Forest City.”[15] Immediately after the Fox sisters left Cleveland, in August 1850, Olcott and others formed a Spiritualist “circle” in Amherst, Ohio.[16]

After some time spent in Ohio, Olcott found himself in Newark, New Jersey, where he learned the latest advances in agricultural science at the model farm of Professor J.J. Mapes. It was here that Olcott got his first taste for journalism, editing Mapes’s magazine, The Working Farmer. He would also publish two books, Sorgho And Imphee, The Chinese and African Sugar Canes (1857,) and Yale Agricultural Lectures (1858.) When the model school closed down, Olcott went to New York, to live with his sister Bella in their family home. At some point during this period, Olcott became a Freemason in New York’s Corinthian Chapter. (The Corinthian Chapter was established in 1856.)[17] In 1859 he found work as the Associate Agricultural Editor of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Though Olcott was connected with the leading anti-slavery journal, he was hardly an Abolitionist. Caring far more about scientific agriculture than politics, he was content to let others “fight their full of the slavery question,” while he attended to the specialty whose development was his primary concern. That would soon change.

~

In September 1859, while Olcott was in Missouri, John Brown was reading his Bible by lamplight in the kitchen of the Kennedy Farmhouse in Maryland.[18] Being only four miles north of his target, Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, the rented domicile served as his home; his barracks; his arsenal. In late September, fifteen boxes containing 198 Sharps rifles and 950 pikes safely arrived in Chambersburg. After much preparation, the day was near at hand. He ordered the women guardians of the conspirators to leave for North Elba. On September 29, the happy spirits of the garrison left with the girls.[19] It was too late to settle the slave question with politics.

Brown first felt the agony of loss when his mother died when he was just a little boy. After her death, he retreated to a world of fantasy within. His father cultivated within him an adamant hatred for slavery, and the belief in the vengeful God of the Old Testament. Though extremely religious, and an enthusiastic member of the Congregational Church, Brown was not blind to their hypocritical position on slavery. Brown married a woman named Dianthe Rusk, but her great sea of emotion was rarely placid. He cared for her as best he could, but this was but another chapter in a book of misfortune. Dianthe and two of their seven children died. Brown eventually married again; his second wife, Mary Ann Day, had thirteen children. Seven of them died in childhood. His litany of business failures (wool, tanning, real estate speculation, etc.) was his only constant. For guidance (and escape) Brown constantly read his Bible. In these ancient Scriptures, he divined that the reason for his many misfortunes was because God had chosen him for a special destiny more important than worldly success. He was the product of his inheritance and environment. Saturated with the Bible, Brown a mystic in his own right, brooded on the ideas of liberty. Had he broken entirely with orthodoxy and put himself forward as the leader of a new religion, his force and gloomy power would have probably resulted in a movement as enormous as that of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young for like Brown, both were products that grew strangely in certain soil conditions of American life.[20]

Over time, after the expected revelation from God seemed not to arrive, Brown sank into depression. In 1855, he left his family in North Elba, New York, and joined five of his sons in the Kansas Territory to begin a new life as a homesteader. Just as soon as he arrived, a bushwhacking war broke out between the Border-Ruffians and Free-Staters. Brown, who loathed slavery, plunged into the Border War with a holy fury that concerned his sons. A volley of violence between the combatants was the Pottawatomie murders, followed by the sacking of Osawatomie, and the killing of his son, Frederick. The shock of his son’s death “loosened” something in Brown’s mind according to relatives, and he released all the frustration and resentment that had built up for over twenty years. It was clear to Brown, though. This was what God wanted. This was the message he was waiting to hear. God revealed to him his special destiny and showed him exactly what must be done through the death of Frederick. He would purify America with fire and irradicate the evil of slavery with an army. To accomplish this, he needed guns, and money…and an army.

Brown knew he needed the support of powerful men. Leaving his sons in North Elba, he launched a fund-raising campaign in all the major hubs, speaking in such cities as Boston, New York, Syracuse, and Philadelphia. In Rochester, Brown stayed in the home of Frederick Douglass, a former slave who escaped the plantation to become a great orator and leading Abolitionist. In the home of Douglass, Brown wrote to the New England thought leaders asking for their support.[21] The talk he gave in Concord, Massachusetts, in February 1858, marked the turning point in his effort. In the audience sat Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Frank Sanborn, and other leading reformers. Brown told the struggles of the Border War in emotional, bloody detail. He told how the Border Ruffians murdered his own son and declared that pro-slavery killers like the Border Ruffians, “had a right to be hung.” (This garnered appreciative nods from Emerson and Thoreau.) Brown said that he believed in two things—the Bible and the Declaration of Independence. “[It is] better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should pass away by a violent death than that a word of either should be violated in this country,” he declared. Emerson, perhaps taken aback, stared at Brown for a moment, nodding his approval when he accepted that Brown was speaking allegorically as he, himself, occasionally spoke. Brown was not a poet. There would be an uprising, Brown assured in the following days. The blood of slaveholders (and their supporters) would flow in the streets. He maintained that it was God’s will that he should incite an insurrection. (A thing that Southerners feared since the Nat Turner uprising in 1831.) He would do this with or without the support of his listeners. Won over by his conviction, a select few agreed to support the plan. Brown then went to Boston and revealed his plan to three prominent Bostonian abolitionists, Theodore Parker, George L. Stearns, and Dr. Samuel G. Howe. Their good friend, and equally militant Abolitionist, Thomas Wentworth Higginson learned of Brown’s insurrection. He, too, wanted to assist. Together with Sanborn and Gerrit Smith, they formed a committee called the “Secret Six.” Though they were certain that the attempted insurrection would fail, it did not matter to them. Brown was adamant in his belief that even if his insurrection plot failed, it would “ignite a powder keg” that would explode into a civil war, and the ultimate destruction of slavery. That, Brown reminded them, was something that the Abolitionists had wanted for years. Though Brown mentioned Virginia in their conversations, no one knew exactly where he intended to strike his blow.

In May, Brown arrived in Chatham, Canada, and had a secret meeting with eleven whites and thirty-four refugee slaves. He told them that the Blacks all over the South were ready to revolt, they simply needed a leader to unshackle them and lead them to freedom. Brown told them that he would invade Virginia, in the region of the Blue Ridge Mountains. From there, he would march into Tennessee and Alabama. He believed that thousands of slaves would rise up and rally around his cause—the most glorious war for freedom in the history of humanity. If and when the troops were against them, he would fight on with a militia trained in guerrilla warfare. For several months Brown raised a militia of whites and former slaves; he planned and prayed, kept on the move. Brown even hired Hugh Forbes (an English Garibaldian) to train them in military tactics.[22] By the autumn, there would be twenty recruits in all (fifteen Whites and five Blacks.) Dangerfield Newby, a freed mixed-race man, joined to liberate his wife and seven children from a plantation near Warrington. (He carried a letter from her in his pocket that read: “Oh dear Dangerfield, come this fall without fail, money or no money I want to see you so much—that is one bright hope I have before me.”) Others in Brown’s militia were John E. Cook (a law clerk from Connecticut,) Charles W. Moffet (a drifter from Iowa,) Aaron D. Stevens (a towering veteran of the Mexican War,) and John Henry Kagi (a young Abolitionist schoolteacher from Ohio,) Charles Tidd, Will Thompson, and William Leeman. Some of Brown’s children joined him in the cause. His sons Oliver and Owen arrived in July. Watson Brown, leaving his young wife and newborn child in North Elba, joined the militia at Kennedy Farmhouse in early August. One of his daughters, Anne, was there, too. (Until he sent her away with Owen’s wife, Martha, on September 29.) They were going to launch their first attack in Harpers Ferry, a town on a thin strip of land situated where the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers met in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Their military objective was the federal arsenal and armory that contained a store of weapons that the raiders desperately needed.

Just before dawn, on October 16, Brown assembled his men in the living room for worship service. At eight o’clock that night, Brown climbed into a wagon burdened with pikes and guns and led his men to Harper’s Ferry. (A rear guard remained at the farm.) Tidd and Cook fell out of line, disappearing into the forest at the sight of the town lights. The others continued walking behind the creaking wagon as it approached the railroad and wagon bridge over the Potomac. Brown made a signal. The men, crouching low, crept across the bridge and captured the night watchman. They continued on, crossing over the Shenandoah Bridge and into the empty streets of Harper’s Ferry. Dangerfield Newby, Oliver Brown, and Thompson stayed behind at the bridges. The others continued on Potomac Street to the arsenal, taking the watchman by surprise. “I came here from Kansas,” said Brown, pinning the watchman against the gate, “and this is a slave State; I want to free all the negroes in this State; I have possession now of the United States armory, and if the citizens interfere with me I must only burn the town and have blood.” Kagi and two of the Black insurgents, Lewis Leary and John Copeland (a former Oberlin College student) then went to man the government rifle works on Shenandoah Street a half-mile north of the armory.

Owen Brown went to the schoolhouse near the farm to rendezvous with some slaves from Maryland that were supposed to join the raiders. At midnight a detachment of raiders returned to the arsenal. They had three hostages with them. Two of the men were a farmer and his son. (Brown’s men freed their slaves and confiscated their household weapons.) The third hostage was a wealthy planter named Colonel Lewis W. Washington, a great-grandnephew of President George Washington. (From his estate, Brown’s men took a sword that Frederick the Great had allegedly given George Washington.)

At 1:30 in the morning, an express train from Wheeling entered Harper’s Ferry. It screeched to a halt when encountering Brown’s guards at a barricade across the railroad bridge. The engineer sent two men down the track to investigate. Brown’s men drove them back with gunshots. The train reversed out of rifle range and stopped. The engineer shouted the alarm.

Shephard Hayward, a free black man who worked at the station as baggage-master, went down the trestlework in search of the night watchman.

“Halt!” shouted one of the raiders.

Hayward kept coming.

The raiders shot Hayward through the heart. Ironically, he was the first casualty in Brown’s war against slavery.

The commotion around the arsenal, by now, had drawn the attention of the villagers and they gathered in the streets with any weapon at hand (knives, axes, flintlocks, etc.) “A slave insurrection!” somebody said. The panic-stricken men fled with their families to the back of the town, in a spot called Bolivar Heights. The bell on the Lutheran Church tolled the alarm, announcing insurrection to farmers all over the countryside. This alarm quickly spread to neighboring towns. Brown had unwisely allowed the express train to push on. It would carry the news to Monocacy and Frederick and be telegraphed to Richmond and Washington, D.C. Very soon the “Negro Insurrection At Harpers Ferry!” would be the front page headline in the newspapers of the East. Meanwhile, militias and lynch mobs in every town and village within a thirty-mile radius of Harper’s Ferry were galvanized to act. Brown was taken completely by surprise at the speed with which the countryside had mobilized against him. Armed farmers and militiamen surrounded Harper’s Ferry and rained fire on the armory where Brown and a dozen of his men were gathered. By eleven o’clock in the morning, a battle raged in the town. Brown did not know what to do. Owen had not arrived with the slaves. The recruits he expected to pour in from Pennsylvania were likewise missing. All the while, militiamen flooded Potomac Street, overrunning the bridges and driving Brown’s men off with blazing muskets. Oliver Brown and Thompson made it back to the armory. Dangerfield Newby, however, shot down with two bullets, was the first of the raiders to die. His wife’s letter was in his pocket when he bled out in the streets. The enraged villagers cut off his ears as a souvenir and left his body to be eaten by hogs.

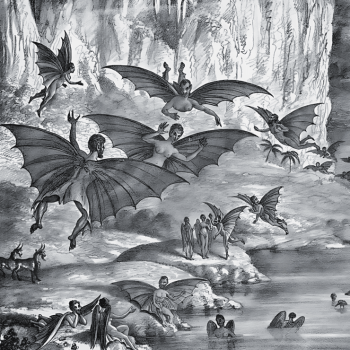

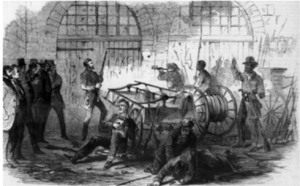

Harper’s Ferry Insurrection.[23]

The only thing Brown could do was to negotiate a ceasefire and offer to release the hostages if the town would let him and his men go free. He sent Thompson out under a flag of truce, but the townspeople grabbed him and took him off to the Gait House at gunpoint. Gathering his remaining force and the hostages in the front of the armory, Brown sent out Watson and Aaron Stevens under another white flag. The mob shot them both down. Watson crawled back to the armory to the feet of his father. A company of United States Marines, dispatched from Washington by President Buchanan himself, soon arrived under Colonel Robert E. Lee. A tall, bearded soldier named Jeb Stuart approached the arsenal under a flag of truce. Brown, with his rifle aimed at Stuart’s head, opened the door and took a note from his outstretched hand. The note demanded that Brown surrender unconditionally, with assurances of protection from the mob, and handed over to the proper authorities. Brown handed the note back and told Stuart that he would only surrender on terms that would allow him and his men to escape. One of the frightened raiders begged Brown to give up and the frightened prisoners wanted Lee to come and reason with Brown personally. While they were arguing, Stuart jumped away from the door and waved his cap. The spectators cheered as the Marines rushed the arsenal. The raiders fired back, but the marines tore down one of the doors with a heavy ladder and stormed the building. Colonel Washington pointed to Brown who was kneeling with his rifle cocked. Lieutenant Israel Green struck Brown with his dress sword before Brown could fire. He tried to run him through with a savage thrust, but the blade, striking Brown’s belt buckle, bent double. When Brown fell to the ground, Green struck him on the head with the hilt of his sword and continued pummeling him until Brown was unconscious.

~

There were Abolitionist supporters in the North who, galvanized by the failed insurrection, supported in what manner they could. The famous minister, Henry Ward Beecher, delivered sermons on the subject at his Plymouth Church in Brooklyn.[24] Like his sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin) he supported the abolition of slavery. Their sister, Isabella Beecher Hooker, was also a social activist and, like Olcott, a Spiritualist.[25] The businessman, Thaddeus Hyatt, “an active anti-slavery man,” thought of a plan whereby he would solicit donations to Brown’s legal fund. [26] (Each donor, in return, would receive a photographic likeness of Brown.)[27] Nevertheless, Horace Greeley was distressed. The people of Virginia, led by Governor, Henry A. Wise, declared war upon the Tribune for its political stance. Three undercover men were already driven from Charlestown and Harper’s Ferry, one after another, on suspicions that they were undercover reporters supplying the Tribune with vivid accounts of the local occurrences. When the letters continued to appear in the Tribune, officials in Virginia announced that they would hang the mysterious unknown on sight. Mob rule asserted itself. The freedom of the press was practically destroyed in America for the first time in its short history. The Tribune correspondent, who was sending his letters by express under the guise of money-packages, eventually found things so hot that he was compelled to leave Charlestown for Baltimore, and from there gather what reports as he could from visitors on the train.[28]

December 2, the date set for Brown’s execution, was fast approaching. It seemed as if the Tribune would be forced to let the day pass without having a correspondent on the ground to tell the friends of Brown how he met his doom. Olcott, seeing that Greeley was worried, volunteered to undertake the job if he would allow him to do it in his own way. Greeley gave a remonstrance about the risks involved (a bounty was still out for the previous Tribune correspondent) but eventually consented. He gave Olcott carte blanche for the mission.

The people waited expectantly (but in vain) for shadowy legions to arrive from over the mountains and rescue the Brown. Governor Wise had already poured so much cavalry and infantry into Charleston that it was practically a military encampment. Sentries were posted in the streets to stop everyone at will and a provost-guard boarded every train. The medical students at the Winchester Medical College hung up the preserved skeleton remains of Watson Brown in a museum. Olcott had not the slightest disposition to have his tanned hide tacked to the door of the jail, with even less desire to figure in the “Book of Martyrs.” It was certainly a problem of the most serious nature for Olcott as to how he would get to Charleston, how he would move about if he got there, and how he would get away with all of his skin.

After considering many expedients, Olcott decided to go to Petersburg and make that his base of operations. Taking passage by steamer, Olcott found himself, late one night, safely landed in the house of an old friend in that city. As Olcott soon realized, this friend “was a fire-eater of fire-eaters, an uncompromising, rank, out-and-out Secessionist, in whose mind Divine right and State rights were convertible terms.” Olcott learned that his host hated John Brown “with the perfect hatred that the Devil is said to bear to holy water.” Exhausted as Olcott was, this friend would not let him go to bed until he had “cursed the hoary old Abolitionist from crown to sole,” and heap “a separate and distinct malediction upon each particular hair of his head and each drop of blood in his veins.” He talked with such rapidity and swore so hard that he did not bother to ascertain Olcott’s sentiments. At that time, however, Olcott was quite ready to express his honest conviction that John Brown’s raid was an inexcusable invasion of a sovereign State.

It was amusing to hear the braggadocio and vaporing of some men in the town when the subject of disunion was brought up in conversation. “Sir,” a prominent lawyer told Olcott at his hotel, “I would be glad to see the whole North sunk to the deepest depths of the bottomless pit! Damn her, we don’t want a union with her, when we can get a foreign market for all our products and receive our necessary articles from thence in exchange! The South has borne with her insolence too long, and it is time, and now is the opportunity for a great United Southern Confederation to show the world the true meaning of the word Republic.”

Olcott found that the Virginians blamed the officers of the law for too much leniency. One of the municipal officers of Petersburg told him it was a lamentable mistake that the whole party was not hanged immediately on the rendition of the verdict. “I would die content if I could see Greeley, Fred Douglass, Emerson, Garrison, and Beecher strung up alongside old Brown on next Friday,” he added.[29]

As the second of December approached, the excitement relative to the execution of Brown increased in the usually torpid town. A deep feeling of rancor and bitter hate against the North had taken possession of the community (a feeling that was not lessened by the “ridicule showered upon Virginian chivalry by the Northern press.”) There was a firm belief that on the day of execution, a rescue attempt would be made. The more excitable people believed that a terrible and protracted civil war would ensue. In deference to the warnings of letter writers (anonymous and otherwise,) and obedient to popular clamor, Governor Wise recalled the previously dismissed troops and would have over two thousand soldiers under arms to guard the gallows. The “Petersburg City Guards” and the “Independent Grays,” militia, who returned Petersburg in late November, were ordered back to Harper’s Ferry. The military spirit being rampant, an effort was also made to organize a cavalry troop.[30]

As rumors spread that Brown’s friends might arrive to free him at the “eleventh hour,” militias arrived in Harper’s Ferry to prevent that from occurring. The militia known as the “Richmond Grays” arrived with an eclectic body of men. Among them was an actor who possessed “much talent,” a certain “J.B. Wilkes,” of the Marshall Stock Company Theatre.[31] It was no secret (the papers said at the time) that “J.B. Wilkes,” was none other than John Wilkes Booth, younger brother of the famous actor, Edwin Booth.[32] Olcott learned from his fire-eating friend that some recruits for the company of “Petersburg Grays” were to go forward to Harper’s Ferry on November 27, on the 5 o’clock train.

Olcott, feigning his desire to assist at the hanging of the “great agitator,” was granted permission to join the party. At the appointed time, the party of recruits met at the railway station, and Olcott was put in charge of Dr. Philip Alexander Taliaferro, the chief surgeon on the staff of his brother, General William B. Taliaferro.[33] Olcott learned that Dr. Taliaferro was a brother Mason and their trip was made agreeable on this account by the close friendship that sprang up between them.[34] As they reached the last station before Charlestown, their train was boarded by the provost-guard. Every passenger was subjected to a rigid examination, but Olcott’s friends in the Grays vouched for him and he was able to pass muster. Harper’s Ferry finally came in sight. Looking out of the car-window, Olcott saw a crowd of Virginians. More than a thousand men, every one of whom had both hands stuffed in their pockets and eyes fixed upon the train. Next to the track stood a provost’s party, wearing uniform caps and other insignia of authority. The captain ordered them to form a line outside the cars, and front face.

Olcott and the doctor, being the only passengers dressed in civilian clothes, naturally attracted a greater share of the public attention. Putting on his best face, Olcott returned stare for stare. His equanimity was soon disturbed. Emerging from the throng was Colonel Colston, an agriculturalist known for his work in the field of sheep husbandry. He published a biography about Thomas Jefferson a year earlier and spent quite some time at Monticello (Jefferson’s estate) near Charlottesville.[35] He was an “impulsive, good-natured, amiable fire-eater,” a man who would clap you on the back and shout out your name, and “wonder what the deuce you are doing there.” The mild face of Colonel Colston seemed, for the moment, to “threaten like that of Nemesis.” A cold sweat started on Olcott’s forehead, fearing that at any moment he would be discovered. Olcott quickly formed and executed a ruse; just as the old fellow got within easy view, he feigned an attack of strabismus, “of the most pronounced type,” and pantomimed expressions that hid his face. The Colonel passed on down the line, and Olcott heaved a sigh of relief.

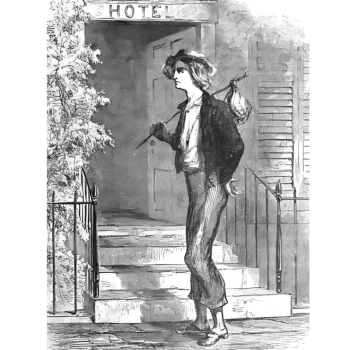

Edmund Ruffin.[36]

Then the Grays right-faced and forward-marched, filing this way and that, until finally reaching their quarters. The small, one-story, building was formerly a law office, with one tiny, cramped room where six men might (uncomfortably) manage to bunk on the floor. As their party giving our party comprised nearly thirty mean, this was a decidedly unpleasant sleeping arrangement. Dr. Taliaferro, however, being of the General Staff, foraged about for better quarters; he took Olcott, his sworn brother and companion-in-arms, along with him. They first went to General Taliaferro’s headquarters at the main hotel. Olcott let him enter alone (as he had no disposition to intrude upon the General’s privacy, nor seek an introduction.) There was a group of men sitting and talking on the porch of the hotel. As Olcott scanned the company, he realized that he recognized one of the men; the old man with long gray hair was none other than Edmund Ruffin, a political and agricultural writer who was a good friend of John C. Calhoun. A bitter hater of the “Yankee race,” he offered to hang John Brown with his own hands. Olcott (who had recently spent some weeks on the Ruffin’s lordly plantation) thought for sure that his time had come. He knew that Ruffin was just as responsible (if not more so) as Governor Wise when it came to exciting the fears and passions of Virginians. Two years earlier, in The Political Economy Of Slavery, Ruffin even commented on the growing appeal of Socialism in the Northern States, stating that “domestic slavery” was the only way that vision could be achieved. “By the single head and master providing all the necessaries for the maintenance and comfort of the laboring class, the contracts, and purchases would be few and on a large scale, and at wholesale prices. There would not, at any time, be a deficiency of food, nor any necessary deficiency of medical or nursing attendance on the sick,” Ruffin writes. “When required by economy, fire and light could be supplied to all at half the cost that would be required separately for each family. Thus, in the institution of domestic slavery, and in that only, are most completely realized the dreams and sanguine hopes of the socialist school of philanthropists.”[37] Olcott knew that Ruffin was one of your impulsive types, “strong in his likes as in his hates.” Friendly as Ruffin was to him (on account of their mutual interest in Agriculture,) he would not for a moment listen to anything Olcott might say by way of explanation, and by announcing his professional affiliation, practically guaranteed his destruction. Olcott got out of this scrape by simply turning his back and walking leisurely away. (The image of that stern, implacable face, however, followed Olcott the entire duration of his stay in Harper’s Ferry.)

At the Episcopal Church, where the Wheeling Battalion was quartered, the soldiers occupied the pews for beds (sleeping on the cushions.) In the adjoining graveyard, some of the soldiers were washing clothes, some cooking, some preparing fuel. On a large tombstone, a party played a game of cards.[38] The billet that Dr. Taliaferro secured was far better than Olcott could have anticipated; it was in the house of one of the principal functionaries of the court, and with the whole Staff of General Taliaferro. While his comrades of the Grays fared wretchedly, Olcott and Dr. Taliaferro had a comfortable room to themselves, a wide French bedstead to sleep in, and bountiful meals to eat. Olcott found the fellows of the Staff to be honest whiskey drinkers and fond of smoking; a good-natured, jolly lot, courteous towards the ladies of the household, and “very cordially disposed towards the New York gentleman who had come down there to help hang John Brown.”

Olcott dusted off the old stock of merry tales, stowed away in odd corners of his head, and passed them around, refurbished, to the company of men. He smoked pipes and drank whiskey with the best of them, sang the comic songs he knew (though always with one eye on the company and the other on the door,) and was generally voted “a capital sort of fellow.” Olcott made no bones about expressing his surprise at the farcically great preparations they had made to hang one poor wounded old man. The Staff was so amicable, however, that even if they discovered that Olcott was going to write a plain, unvarnished account of the execution, it probably would not make much of a difference in their relations. What made Olcott feel worse than all was going through the town, arm in arm with some of his new friends, “cheek by jowl and all that sort of thing,” while thinking how shameful, pitiful, and cowardly it was that in this “land of the free and home of the brave,” he was walking those streets with the specter of Death stalking lock-step behind him, never leaving him day or night, because he dared to write an honest letter to a great newspaper, and tell how a brave (if perhaps fanatical) man behaved and talked.

All this time, the mysterious Tribune man vexed the peace of the whole South. (The Charlestown papers indignantly repudiated the idea that any such person was in the place.) The newspapers of the Gulf States called upon the Virginians to “clean out the reptile!” General Taliaferro proclaimed that all strangers should report themselves to the provost for examination. Colonel Taylor, the puffy militiaman, notified the artist of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper that he was suspected and must clear out. Dr. Augustus Rawlings, however, the correspondent of said newspaper, was the only reporter from the North that was permitted to interview Brown in his jail cell. (It was through the persistence of Dr. Rawlings that the order excluding the Press was partially rescinded and allowed to witness the execution.)[39] Olcott’s predecessor, who pertinaciously stuck to his post, faithfully chronicling the events at Charlestown, had “set the sensible people of the whole country to laughing at the cowardly behavior of the villagers.” Successfully concealing his identity, his predecessor rubbed salt into the wounds that his keen lance inflicted, and the community was furiously distracted. The night before the execution, Olcott opened up this matter to Dr. Taliaferro, and with charming naiveté, asked him to speak candidly and explain how this Tribune man continued to elude the vigilance of the people.

Dr. Taliaferro drew his chair up to Olcott. “I’ll tell you how it is,” he said, leaning in with a confidential whisper. “You see our local papers publish accounts of what is transpiring here, and somebody connected with the Tribune gets hold of these papers in New York City, and then writes a letter at the Tribune office and dates it from Charlestown. Of course, I needn’t tell you that, in their present state of excitement, our people would be more than likely to hang such a person to the nearest tree. You know some hot-headed fellows have even offered a reward for him.”

Olcott laughed with all his heart. “That is a Yankee trick I hadn’t thought of!” he said, slapping Dr. Taliaferro on the knee.

Then a dreadful realization crept into Olcott’s mind. “The wretched trunk!” On the morning after his arrival, something was said about the lot of trunks and things they had down at the Provost Marshal’s office. He suddenly remembered that, in the excitement of my encounter with Colonel Colston, he had quite forgotten his luggage (which had undoubtedly gone to the provost’s with other unclaimed or suspicious property.) It was marked with his initials, and the words “New York.” Given the current temperamental climate in which the people of Charlestown were now in, this was enough to place its owner in no little personal jeopardy. It occurred to Olcott that perhaps at that moment they were, to use a Southern expression, “gunning,” after the person in question. It was a real dilemma. He did not know what to do. Olcott cudgeled his brains for an hour to no purpose. To be able to get it away himself, without imminent danger of discovery (and the defeat of his mission,) was an impossibility. It was equally dangerous to leave it unclaimed, for as it came up with the Grays’ reinforcements, its owner would be certainly hunted down. It was, simply put, a matter of life and death. As a last resort, Olcott determined to try what his Masonry would do. He picked out a fine, brave young fellow of the Staff, a perfect gentleman, and, under the seal of Masonic confidence, told him who he was, and directed him to go to the Court House, and claim and bring away the trunk. He did it, and Olcott was safe.

On November 29, 1859, Governor Wise seized the Winchester and Potomac Railroad for military purposes. He then issued his proclamation to the people of Virginia, cautioning them to remain “at home and on guard or patrol duty on the 2nd of December, and to abstain from going to Charlestown.” He said: “Orders, are issued to prevent women and children, and strangers are hereby cautioned that there will be danger to them in approaching that place, or near it, on that day. If deemed necessary, martial law will be proclaimed and enforced.”

Then the morning of December 2, 1859, arrived. The field of execution—a plot of about forty acres, half in sod and half corn-stubble—was directly opposite the house that Olcott and the Staff occupied. The gallows stood on a rising ground a yards away from the porch. A military force of about three thousand troops (artillery, cavalry, and infantry) was concentrated at the place. The fifteen miles surrounding the nucleus of Harper’s Ferry was guarded by mounted and foot soldiers. All traffic between town and country was stopped. A field-piece loaded with grape and canister was planted directly in front of and aimed at the scaffold, to blow Brown’s body into smithereens in the event of attempted rescue. Other cannon commanded the approaches to the town. All Virginia held breath until the noontide should come and go. The most stringent precautions were taken to prevent even the townspeople from approaching the outermost line of patrolling sentries, for the authorities were determined to choke Brown without giving him a chance to make any seditious speeches.

The December sun had risen clear and bright but soon passed into a bank of haze. Olcott was afraid they would have a stormy day of it. By nine o’clock, however, the sun hung beautifully in an azure sky. Though it was winter, the sun became so hot, that doors and windows were flung wide open. The ground was staked the day before, and fluttering white pennons all around the lot marked the posts of the sentries. Then a strong force of volunteer cavalry, wearing red flannel shirts and black caps and trousers, rode up and were posted (fifty paces apart, around the entire field.) Then the guns and caissons of the artillery rumbled up; then more cavalry and infantry came.

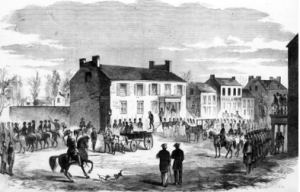

Execution Of John Brown In Front Of The Jail.[40]

A solemn hush settled over the awful scene. All was quiet save the twittering of birds, the toothless whistling of the south wind in the tree branches, and, occasionally, the impatient stamp of a horse’s hoof on the greensward. All eyes were turned to the jail a half-mile away down the road, but nothing could be seen in the bright sunshine except the glint of bayonets, gilt buttons, and straps. The mass opened right and left, and a wagon, drawn by two white horses, came into view. In this long box hearse sat Brown, upright and stoic. He wore a black suit, a black slouch hat on his head, and blood-red slippers on his feet. The melancholy cortége formed and advanced towards the spectators. Brown, the one helpless old man, suffering from five saber and bayonet wounds, went to his death with an escort of five squadrons. (Major Loring’s “Battalion Of Defensibles,” Captain William’s “Montpelier Guard,” Captain Scott’s “Petersburg Grays,” Captain Miller’s “Virginia Volunteers,” and Captain Rady’s “Young Guard.”)

“Now, isn’t that pitiful?” Olcott thought, As the head of the column filed into the field, between the loaded howitzers. “Isn’t it enough to make a stone image blush, to think of all this great army, with its flying flags, and its brass guns, and its videttes and patrols all the way up to the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, haling one wounded Kansas farmer to execution?” Olcott looked upon the majestic face of Brown. For an instant, their eyes met. Whether Brown read anything in his of the thoughts that crowded his mind Olcott could not say, but an expression of intense inquiry came into his, but he gave Olcott a glance he would never forget. As Brown’s wagon turned in from the dusty road, and the whole array of military was presented to his view, the old man straightened himself up on his coffin and proudly surveyed the scene. He looked to Olcott like Caesar passing in his triumphal chariot through the streets of Rome. He bore the searching gaze of the soldiery with a kingliness of manner as if he were receiving homage that was his due and did not cower under it, as if he were a malefactor about to be punished for some crime he had committed. Brown fully appreciated the effect of all this display of military upon public opinion, for he said one day in prison: “I am not sure but the object I have in view will be better served by my dying than by my living; I must think of that.”

The cortége passed through the triple squares of troops, and over the hillock, winding around the scaffold to the easterly side, and halted. The bodyguard (Olcott’s company of Grays) opened ranks. Brown descended, with self-possession and dignity, and mounted the steps of the gallows. He looked about at earth, sky, and people, and remarked to Captain Avis, his jailer, upon the beauty of the scene. Brown’s eye lingered wistfully upon the few civilians who were permitted to gaze from a distance upon the tragedy, as if (so it seemed to Olcott) he longed for a glimpse of one friendly face. With another glance at the sky and the far-away Blue Ridge Mountains, Brown turned to the sheriff and signified that he was ready. His slouch hat was removed, his elbows and ankles pinioned, and a white hood was drawn over his head. The world was gone from his sight forever.

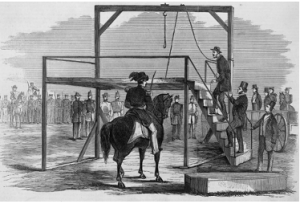

John Brown Ascending The Scaffold Preparatory To Being Hanged.[41]

One might imagine, after the indecent haste to get Brown tried, convicted, sentenced, and hung, the authorities would have dispatched the old man as soon as possible. This was not the case. There was still the shadow of a possibility that some soldiers might spring out of the dull sod of that field. So the troops were ordered hither and thither, marching and counter-marchings. Olcott stood there, watch in hand. It was eight minutes (though it seemed like centuries) before Colonel Scott, losing patience, gave the signal. Sheriff Campbell cut the rope. The trap fell, and with a wailing screech of its hinges, Brown’s body hung twirling in the air. There was but one spasmodic clutch of the tied hands, and a few jerks and quivers of the limbs, and then all was still. Twenty minutes later, the Charleston surgeons went up and lifted the arms and dropped them like lead. Then they placed their ears to the chest and felt the wrists for a pulse. Then the military surgeons had their turn of it. After a consultation, they stepped back and left the body to dangle by its neck for another eighteen minutes, swinging, pendulum-like, from the force of the rising wind. Brown, at last, was declared dead, and the body, “limp and horrid, with an inch-deep groove cut into its neck” by a rope donated by a Kentucky hemp halter, was lowered down, and slumped into a heap. The body was then put into a black-walnut coffin and lifted into the wagon again. The body-guard closed in around the wagon, and the cavalry moved off.

Comments from the crowd were barbaric. Some said that Brown’s head ought to be cut off and preserved at the Winchester Medical College, along with the dissected body of his son. Some expressed the wish that they ought to have had the body fall ten feet (instead of a fall of eighteen inches) to snap his head off. Others wanted the authorities to stuff a dose of arsenic into the corpse’s mouth, to effectually prevent his Abolition friends from resurrecting him. But then, on the other hand, there were some gentlemen, and among others, a Captain in Taliaferro’s Staff, who expressed their admiration for Brown’s splendid pluck. The latter person sat next to Olcott at the table that night. When Olcott asked him what he thought of the affair, he turned a sparkling eye upon him and said. “By God, sir. He’s the bravest man that ever lived!”[42]

SOURCES:

[1] “Public Meetings: North American National Convention.” The New York Daily Tribune. (New York, New York) June 16, 1856.

[2] “The Harper’s Ferry Insurrection.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Vol. VIII, No. 207 (November 19, 1859): 383-384.

[3] Etcheson, Nicole. “‘A Living, Creeping Lie’: Abraham Lincoln On Popular Sovereignty.” Journal Of The Abraham Lincoln Association. Vol. XXIX, No. 2 (Summer 2008): 1–25.

[4] Andrews, Jr., Horace. “Kansas Crusade: Eli Thayer And The New England Emigrant Aid Company.” New England Quarterly. Vol. XXXV, No. 4 (December 1962): 497-514.

[5] Sanborn, Franklin. “John Brown In Massachusetts.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. XXIX, No. 174 (April 1872): 420-433.

[6] Murphet, Howard. Hammer On The Mountain. The Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1972): 1-3.

[7] Oates, Stephen B. “John Brown’s Bloody Pilgrimage.” Southwest Review. Vol. LIII, No. 1 (Winter 1968):1-22.

[8] “Proceedings Of The St. Louis Railroad Convention.” The Charleston Courier. (Charleston, Missouri) October 14, 1859.

[9] Olcott, Henry Steel. “How We Hung John Brown.” Essay. In Lotos Leaves: Original Stories, Essays, and Poems By The Great Writers Of America And England. (eds.) Brougham John; Elderkin, John. William F. Gill And Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1875): 233–249.

[10] Ormsby, Robert McKinley. A History Of The Whig Party. Crosby, Nichols & Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1859): 13.

[11] Gilman, Sander L. “Karl Marx and the Secret Language of Jews.” Modern Judaism. Vol. IV, No. 3 (October 1984): 275-294.

[12] Gomez, Adam. “Deus Vult: John L. O’Sullivan, Manifest Destiny, and American Democratic Messianism.” American Political Thought. Vol. I, No. 2 (September 2012): 236–262.

[13] “Greeley Among The Ghosts.” The Evening Post. (Cleveland, Ohio) June 13, 1850.

[14] Grossman, James. James Fenimore Cooper. Stanford University Press. Stanford, California. (1949): 246.

[15] “‘The Mysterious Rappings.’” The Evening Post. (Cleveland, Ohio) August 14, 1850; Britten, Emma Hardinge. Modern American Spiritualism: A Twenty Years’ Record Of The Communion Between Earth And The World Of Spirits. [Third Edition.] Emma Hardinge Britten. New York, New York. (1870): 297-303.

[16] (ed.) Brittan, S.B. The Spiritual Telegraph: Vol. III. Partridge & Brittan. New York, New York. (1854): 569-580. (“The New York Conference.”)

[17] Jinarajadasa, C. “the Early History Of The T.S.: Part VII.” The Theosophist. Vol. XLIV, No. 6 (March 1923): 643-650.

[18] Villard, Oswald Garrison. John Brown, 1800-1859: A Biography Fifty Years After. Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1910): 420.

[19] Oates, Stephen B. “John Brown’s Bloody Pilgrimage.” Southwest Review. Vol. LIII, No. 1 (Winter 1968):1-22.

[20] Knowles, John Harris. From Summer Land To Summer. Frederick Humphreys. New York, New York. (1899): 151-152.

[21] Sanborn, Franklin. “John Brown And His Friends.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. XXX, No. 177 (July 1872): 49-61.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Harper’s Ferry Conspiracy.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Vol. VIII, No. 205 (November 5, 1859): 351-352,358-359.

[24] “Henry Ward Beecher On The Insurrection.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) November 1, 1859; Abbott, Lyman. Henry Ward Beecher: Vol. III. Houghton, Mifflin And Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1903): 220, 288.

[25] “Sudden Death Of Kate Fox.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) July 4, 1892.

[26] “Thaddeus Hyatt Dies On The Isle OF Wright.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) July 26, 1901.

[27] “A New Revolutionary Movement–Complicity Of Republican Leaders With John Brown Rebellion.” The New York Daily Herald. (New York, New York) November 18, 1859.

[28] Greeley, Horace. The American Conflict: A History Of The Great Rebellion In The United States Of America, 1860-’64: Vol. I. O.D. Case & Company. Hartford, Connecticut. (1864): 279-299.

[29] “John Brown’s Invasion.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) November 29, 1859.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Fuller, Jr., Charles F. “Edwin And John Wilkes Booth. Actors At The Old Marshall Theatre In Richmond.” The Virginia Magazine Of History And Biography. Vol. LXXIX, No. 4 (October 1971): 477-483.

[32] “Mr. J.B. Wilkes.” The Louisville Daily Courier. (Louisville, Kentucky) November 28, 1859.

[33] Philip Alexander Taliaferro was a surgeon, and brother of William Booth Taliaferro. [Hueval, Sean M; Heuval, Lisa. The College Of William And Mary In The Civil War. McFarland & Company, Inc. Jefferson, North Carolina. (2013): 180.] In “How We Hung John Brown,” Olcott writes: “The doctor and I, being the only ones of the passengers dressed in citizen’s clothes, naturally attracted a greater share of the public attention than was at all gratifying.” In Olcott’s account in The Tribune he writes: “This morning, Col. Taliaferro, brother of the commander-in-chief, was surprised coming into town without uniform, was set upon, captured, and reduced to much subjection, before he could make good his identity.” [“The Execution Of John Brown.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) December 3, 1859.]

[34] Olcott, as indicated by his diplomas, became a member of New York’s Corinthian Chapter, Royal Arch, No. 159 on dated January 12, 1860, a month after this encounter. (Olcott’s Master Mason’s diploma from Huguenot Lodge, No. 448 is dated December 20, 1861.) [Jinarajadasa, C. “the Early History Of The T.S.: Part VII.” The Theosophist. Vol. XLIV, No. 6 (March 1923): 643-650.] As Royal Arch was advanced degree Masonry, Olcott was presumably inducted into the Brotherhood at an earlier time than 1860. At the Convention of New York Freemason in June 1860, Olcott “presented a petition from a number of non-affiliated Masons at Batavia which was, on motion, referred to the Committee on Grievances.” Perhaps the connection lies there. [Grand Lodge Of New York. Proceedings Of The Grand Lodge Of Free And Accepted Masons Of The State Of New York. Macoy & Sickels. New York, New York. (1860): 167.]

[35] Olcott states: “for who should come poking through the throng but my old Washington acquaintance, Colonel Blank, the great sheep-breeder…” This could have been Henry Stephens Randall, author of Sheep Husbandry In The South. [Randall is mentioned as “Col. Randall” in the 1860 edition: Randall, Henry Stephens. Sheep Husbandry In The South. Orange Judd & Company. New York, New York. (1860): 3-6.] An article from 1859 states: “Mr. Randall, who has been secretary of the State of New York, has published a book on raising sheep. His statements have been indorsed by eminent agriculturalists at the north, and without doubt are to be relied upon.” [“Sheep Husbandry.” True Democrat. (Little Rock, Arkansas) March 9, 1859.] It is possible that Randall was there in connection with the publication of his three-volume biography of Thomas Jefferson that was published in 1858. (Jefferson’s estate, Monticello, was in Charlottesville, Virginia.) [Randall, Henry Stephens. The Life Of Thomas Jefferson. Derby & Jackson. New York, New York. (1858.)] He was known to converse with Jefferson’s relatives at Monticello as indicated in his letters: “The ‘Dusky Sally Story’—the story that Mr. Jefferson kept one of his slaves, (Sally Henings) as his mistress and had children by her, was once extensively believed by respectable men, and I believe both John Quincy Adams and our Bryant sounded poetical lyres on this very poetical subject! Walking about mouldering Monticello one day with Col. T. J. Randolph (Mr. Jefferson’s oldest grandson) he showed me a smoke blackened and sooty room in one of the collonades, and informed me it was Sally Henings’ room. He asked me if I knew how the story of Mr. Jefferson’s connexion with her originated. I told him I did not. ‘There was a better excuse for it, said he, than you might think: she had children which resembled Mr. Jefferson so closely that it was plain that they had his blood in their veins.’ He said in one case that the resemblance was so close, that at some distance or in the dusk the slave, dressed in the same way, might be mistaken for Mr. Jefferson—He said in one instance, a gentleman dining with Mr. Jefferson, looked so startled as he raised his eyes from the latter to the servant behind him, that his discovery of the resemblance was perfectly obvious to all. Sally Henings was a house servant, and her children were brought up house servants—so that the likeness between master and slave was blazoned to all the multitudes who visited this political Mecca. Mr. Jefferson had two nephews, Peter Carr and Samuel Carr whom he brought up in his house. There were the sons of Mr. Jefferson’s sister and her husband Dabney Carr that young and brilliant orator, described by Wirt, who shone so conspicuously in the dawn of the Revolution, but died in 17—. Pete was peculiarly gifted and amiable. Of Samuel I know less. But he became a man of repute and sat in the State Senate of Virginia. Col. Randolph informed me that Sally Henings was the mistress of Peter, and her sister Betsey the mistress of Samuel—and from these connections sprang the progeny which resembled Mr. Jefferson. Both the Henings girls were light colored and decidedly goodlooking. The Colonel said their connexion with the Carrs was perfectly notorious at Monticello , and scarcely disguised by the latter–never disavowed by them. Samuel’s proceedings were particularly open.” [Henry S. Randall’s Letter To James Parton. Courtland Village, New York. June 1, 1868.] Olcott, however, mentions that the “Colonel Blank” was “blood-thirty,” a trait that does not seem to fit with what we know of Colonel Randall. Colonel Edward Colston is a more likely candidate, as stated in Sheep Husbandry, “Colonel Edward Colston, of Berkley County, Virginia,” also practiced sheep husbandry. [Randall, Henry Stephens. Sheep Husbandry In The South. Orange Judd & Company. New York, New York. (1860): 46-47.]

[36] Lossing, John Benson. The Pictorial Field Book Of The Civil War In The United States Of America: Vol. I. T. Belknap. Hartford, Connecticut. (1874): 48.

[37] Ruffin, Edmund. The Political Economy Of Slavery. Lemuel Towers. Washington, D.C. (1857): 10.

[38] “The Execution Of John Brown.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) December 3, 1859.

[39] “The Execution Of John Brown.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) December 3, 1859.

[40] “The Harper’s Ferry Insurrection.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Vol. IX, No. 211 (December 17, 1859): 33, 39-41.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Olcott, Henry Steel. “How We Hung John Brown.” Essay. In Lotos Leaves: Original Stories, Essays, and Poems By The Great Writers Of America And England. (eds.) Brougham John; Elderkin, John. William F. Gill And Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1875): 233–249.