“I have, I know, been told that this correspondence may have been forged from first to last by a man whose imagination had certainly been fed on the most seductive tales.”—Gaston Leroux (The Phantom Of The Opera.)[1]

~

On the evening of the January 14, 1858, the carriage of Napoleon III winded through narrow, sinewy streets, through a crowd which grew in density. It was only when the emperor and his coterie approached the entrance of the Salle Le Peletier Opera House, did the conspirators find their opportunity. The grenades exploded immediately at the concussion of the fall. The carriage was shattered. The street was filled with clamor and consternation. The dead and dying were strewn all around. The emperor and empress, however, escaped unharmed.

Felice Orsini, the would-be assassin, was quickly apprehended with his co-conspirators. An Italian refugee, Orsini was “one of the most desperate of Italian revolutionists.” He had already been implicated in a conspiracy in his youth, for which he was sentenced to life in prison, but the general amnesty granted by Pope Pius IX restored him to liberty. The Sardinian Government expelled him from Italy in 1853, after which he went to London. It was here that Orsini associated himself with Giuseppe Mazzini and the other leading European revolutionaries who took refuge in the city. Orsini came to believe that Napoleon III was the greatest obstacle to the success of revolutionary movements throughout Europe, so he went to Paris under a false name, resolved to assassinate the emperor. On March 13, Orsini breathed his last in the lunette of a guillotine.[2]

Giuseppe Mazzini. (Wiki)

After a failed assassination attempt, city planners realized that the constricted streets of Paris were in need of an upgrade for the safety of the Emperor. Georges Eugöne Haussmann was chosen to conduct a massive urban renewal program that would, among other things, widen the boulevards and erect a new theatre. When construction began on the new theatre, the Garnier Opera House, it was discovered that the groundwater level of the site was surprisingly high. A double foundation was built to protect the superstructure, but rumors soon spread throughout Paris that new opera house was built over a subterranean reservoir.[3] Paris, in many respects, became unrecognizable; with the demolition of slums and the corresponding rise in rents, the poorest citizens were hit the hardest.[4] If the future looked uncertain, there was solace in the past

In nineteenth-century, the Church and State in France were locked in a prolonged battle for the hearts and minds of the people, exemplified in the semiotics of “Marianne” (State,) and the Virgin Mary (Church.)[5] The dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary took on a crucial role at this time. Although a long-held Catholic belief, it did not officially become doctrine until 1854.[6] The more secular the nation became, the greater the spiritual pushback. This manifested in some peculiar ways, namely the unprecedented number of supernatural religious manifestations which occurred (namely religious manifestations of the Virgin Mary.) There were so many heavenly visions, in fact, that it was referred to as an “epidemic of apparitions.” The most famous of these being the apparition of the Virgin Mary at Lourdes, which began immediately following Orsini’s assassination attempt of Napoleon III.

Virgin Mary at Lourdes. (Wiki.)

~

On March 18, 1896, the Virgin Mary began appearing in the village of Tilly-Sur-Seulles.[7] The first to lay witness was a young school girl in the Convent School. The nun who taught the class told her pupils that they should be exceptionally good on the eve of St. Joseph’s day, to deserve a reward from the Holy Virgin. It was then that the little girl cried out, “Look out of the window, madame; there is the good Virgin!”

The nun and fifty other students turned to look, and saw what looked like the Virgin with the Infant in her arms. The villagers would later claim that the same vision (the Virgin holding the Infant in her arms) was frequently seen under an elm in a field at the top of the hill.[8] The Virgin appeared on Holy Thursday, covered in a veil, and on Easter Monday She was visible all day. This, the villagers claimed, was in accordance with the prophecy of Vintras, a famous exorcist from Tilly-Sur-Seulles (who once claimed that the Archangel Michael told him that he was the reincarnation of the prophet Eli.) Tilly-Sur-Seulles became a site of pilgrimage overnight, with thousands of visitors arriving to catch a glimpse, and make relics from the barks of the trees at the holy spot.[9] Then another girl, Louise Potiniere, became the “miracle-monger,” experiencing visions of the Virgin more than anybody else. But the character of the Visions had changed. Sometimes in the place of Mary, there were chapels, angels, statues, and globes of fire which seemed to come out of the ground enveloped in a cloud which gradually dissipated. On Ascension Day, 200 witnesses claimed to have seen a rosy cloud; though they were split on whether it appeared as the entire scene of Calvary of a single cross. Those who tried to play on the credulity of the pilgrims testified as to being “hunted by three fiery bullets at which they fired their revolvers in vain.” Others began witnessing headless and bloody phantoms, hear invisible bells ringing, and a lion devouring its prey. One of the notable women who arrived in Tilly was simply referred to as “The Woman in Black,” who was “constantly beset with a vision of Legion.”[10]

The site of the Apparitions at Tilly-Sur-Seulles.[11]

Canon Brettes officially denounced the visions as Tilly as “diabolic” in origin. Indeed, it was said at the time that France was “girded by diabolical manifestations.” It was in keeping with the general “psychic” atmosphere of the time. While this phenomenon was occurring in Tilly-Sur-Seulles, for example, the French Psychical Research Society was investigating a violent haunting in Le Perreux, which featured a terrifying disembodied voice.[12] Whatever was happening, it had even caught the attention of the men of science. Gustave Le Bon, whose 1895 work, Psychologie des Foules (The Crowd,) explored the topic of mass hallucination.[13] Emile Durkheim, likewise, would explore the uneasy soul of France in his 1897 work, Suicide. As for France being “girded by diabolical manifestations,” that requires a bit of an explanation.

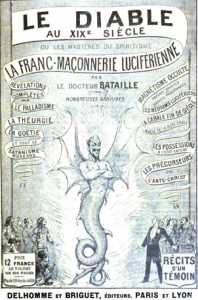

In 1854, the year that Immaculate Conception of Mary became dogma, a man named Léo Taxil was born in Marseille. A Jesuit-educated journalist, Taxil turned his back on the Church in early adulthood. Influenced by Freemasonry, his writing took an anti-clerical stance. (He would declare French Republicanism as his creed.) Taxil later became an outspoken critic of Freemasons, though he remained anti-clerical. In his 1886 work, Le Culte du Grande Architecte, Taxil claimed that Satan was the divinity whom Freemasons worshipped. In subsequent works, Taxil made his case for why Masons were danger to religion, society, and human decency in general. In 1891 he said he possessed knowledge of a secret androgynous Lodge of high-grade Masons known as Palladists, who had a Luciferian creed, and endeavored political subversion. This announcement was on the heels of Joris-Karl Huysman’s 1891 novel, Là-Bas, (The Damned,) which described “the hysterical and criminal rites” of Satanists who had allegedly infiltrated, and taken over, the Catholic Church.[14]

“Le Diable au XIXe Siècle.”[15]

In 1894, Taxil began his hoax with the publication of his book, Le Diable au XIXe Siècle (The Devil In The Nineteenth Century.) The work, however, was not under his name; rather, Taxil convinced a German free-thinker named Charles Hacks to adopt the literary persona of “Dr. Bataille” and take credit for the work. In the work, “Bataille” claimed to have met a representative of a global cult of “diabolists,” and joined them in the fraternity to expose their secrets. The work acts as a survey of black magic and witchcraft, from antiquity until the fin de siècle. “Bataille” claimed to have visited the Sanctum Regnum of Palladic Freemasonry in Charleston, South Carolina. It was there, “Bataille” stated, that the skull of Jacques de Molay (Grand Master of Knights Templar,) and Templar idol, Baphomet, were preserved. This group was the continuation of an ancient cult of devil-worshippers which survived in the elite circles of various groups (Jews, Mormons, Knights of Pythias, Oddfellows, etc.) As for the meat of the story (with a cast that includes Lucifer, and the demons Beelzebub, Astaroth, and Asmodeus) it went something like this:

The Palladic Order was a new work of Satan, carried out by his servant, General Albert Pike (a well-known Scottish Rite Freemason in America,) on September 20, 1870, on the occasion of the Italian occupation of the Papal States. Its purpose was to annihilate Catholicism (and Christianity broadly,) and usher in the reign of the Antichrist. It would carry this out through assassinations and media manipulation. Pike was in charge of the religious side of the Palladic Order with its aforementioned Sanctum Regnum beneath the Masonic Temple in Charleston. The political directorate of Palladism was located in Rome, under the guidance of the Italian revolutionary, Giuseppe Mazzini. When General Pike died, Mazzini folded the religious work into his department in Rome, where the Antichrist was said to return. When Mazzini died, he was succeeded by Adriano Lemmi.

Albert Pike. (Wiki)

Diana Vaughan. (Wiki)

In the concluding chapters of the work, “Bataille” introduces Diana Vaughan, the aristocratic Franco-American Grand Mistress of the Triangle Phoebe-the-Rose of New York. With a pedigree that stretched back to Venus-Astarte, Vaughan was an honored woman in the Palladic Order, having gained favor with Lucifer himself. (In reality, Vaughan was Taxil’s personal typist.) She came forth with an exposé of the group, she said, because of a schism within the ranks. Lemmi had lead the Palladic Order to adopt a creed of Satanism, or “devil-worship.” Vaughan, like General Pike, was Luciferian.[16] This seemingly contradictory statement can be explained by the internal cosmology of the Palladic Order. Lucifereans believed in a “reversed Christianity” (in the vein of the Manichean heresy,) whereby spiritual duality was represented by Lucifer (a god of light) and Adonai, or Satan (prince of darkness.) For Lucifereans, Jesus was the Christ of Adonai, and thus was the messenger of misfortune and lies. The Antichrist of the Palladic Order, therefore, was a messianic figure of truth and light.[17] Before Taxil admitted to the hoax, his story took on a life of its own, or perhaps it is better to say that it entered the mélange of diabolism already existent. The general public was made aware of the “two entirely different cults—that of the Satanists […] and that of the worshippers of Lucifer, who stand upon an entirely different plane.”[18] Arthur Edward Waite (who would produce the popular tarot deck in 1909) published Vaughan’s story in his 1896 work, Devil Worship In France. Waite writes:

To be plain the Question of Lucifer has reappeared, and in a manner which must be eminently disconcerting to the average intelligence and the advanced and strong in mind. It has reappeared not as a speculative inquiry into the possibility of a personal embodiment of evil operating mysteriously, but after a wholly spiritual manner, for the propagation of the second death; we are asked to acknowledge that there is a visible and tangible manifestation of the descending hierarchy taking place at the close of a century which has denied that there is any prince of darkness.[19]

Through Waite’s work, many in the Anglophone world came to believe that “devil-worship” was “not a sensational fabrication.”[20] Like their French brethren, their minds were opened “to the fact that Lucifer was a very real and very living force in our own midst.[21] (Curiously, a “devil-scare” broke out in a school in New York at the same time.) The San Francisco Examiner even writing:

Had it has been asked, say, a years ago. “What is modern Diabolism? Who are its disciples? Where is devil worship practiced? And why? The questioner would have been thought man. It is true that the terms Satanism, Luciferianism, Diabolism, and their equivalents have been buzzed about, although with much vagueness, for several years in a manner to indicate some living terror rather than an exploded superstition. In France this question of Lucifer has recently appeared in the French courts, and the extraordinary suit now pending in the Paris courts continues to reveal astounding facts relating to the cultus diabolicus.[22]

Early in 1896, a woman named Lucie Claraz of Freiburg, Switzerland, sued a prominent Parisian Catholic periodical for publishing the statement that she was a “devotee of the satanic rites, practiced by devil-worshippers.” As the trial progressed, Claraz’s attorney successfully proved that “diabolical services were celebrated in at least three places in the Paris, that the mock masses were said before the crucifix turned upside down, the hosts used having been stolen from those consecrated in churches—in short, that almost all the revelations contained in the ‘Black Mass.’”[23]

The topic (whether one believed in the devil or not) became fashionable. Sarah Bernhardt would even capitalize on the interest in Victorien Sardou’s play, “Spiritisme.”[24] Perhaps it was just a coincidence, or perhaps not, but in May 1896, in the midst of all this “diabolism,” the half-ton counterweight to the great chandelier in the Opera Garnier fell through the ceiling, and into the gallery. It was during a performance of Hellé, and at least one woman was killed, with many others were being injured. This mix of legend of the subterranean reservoir and the chandelier would later be included in Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera. It was the story of another kind of apparition.[25]

SOURCES:

[1] Leroux, Gaston. The Phantom Of The Opera. Grossett & Dunlap. New York, New York. (1911): 4.

[2] Abbott, John Stevens Cabot. The History Of Napoleon III, Emperor Of The French. B.B. Russell. Boston, Massachusetts. (1873): 565-567.

[3] Higgins, Shawn. “From The Seventh Arrondissement To The Seventh Ward: Blavatsky’s Arrival in America 1873.” Theosophical History: A Quarterly Journal of Research. Vol. XIX No. 4. (October 2018): 158-171.

[4] Hogle, Jerrold E. The Undergrounds Of The Phantom Of The Opera. Palgrave. New York, New York. (2002): 70-73.

[5] Ziolkowski, Jan M. The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity: Volume II: Medieval Meets Medievalism. Open Book Publishers. Cambridge, England. (2018): 51-95.

[6] Garrigou-Kempton, Emilie. “Hysteria In Lourdes And Miracles At The Salpêtrière: Making Sense Of The Inexplicable In Charcot’s La Foi Qui Guérit And In Zola’s Lourdes.” In Quand La Folie Parle: The Dialectic Effect of Madness in French Literature Since the Nineteenth Century. (eds.) Gillian Ni Cheallaigh, Laura Jackson, Siobhan McIlvanney. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, England. (2014): 53-73.

[7] “The Tilly-Sur-Seulles Visions.” The Standard. (London, England) May 26, 1896.

[8] “The Tilly-Sur-Seulles Visions.” The Graphic. (London, England) June 20, 1896.

[9] “A Schoolgirl’s Hallucination.” The North-Eastern Daily Gazette. (Middlesborough, Cleveland, England) April 20, 1896.

[10] “Psychical Manifestations.” The Age. (Melbourne, Australia) September 26, 1896.

[11] “The Apparitions In Normandy.” Black And White. Vol. XII, No. 289. (August 15, 1896): 214.

[12] “The ‘Devil’ In France.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) July 8, 1896.

[13] There was evidently something “in the air” in the mid-1890s. French sociologist, Gustave Le Bon, explored this phenomena in The Crowd (1895) in which he writes: “[Sentimental] Contagion […] intervenes to determine the manifestation in crowds of their special characteristics, and at the same time the trend they are to take. Contagion is a phenomenon of which it is easy to establish the presence, but that it is not easy to explain. It must be classed among those phenomena of a hypnotic order.” [Le Bon, Gustave. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. The MacMillan Company. New York, New York. (1896): 33.]

[14] “The Real Lucifer.” The Westminster Budget. (London, England) February 21, 1896.

[15] Taxil, Léo. Le Diable au XIXe Siècle: Ou, Les Mystères du Spiritisme, la Franc-Maçonnerie Luciférienne. Delhomme et Briguet. Paris, France. (1894): Front cover.

[16] Jones, W.R. “Palladism And The Papacy: An Episode Of French Anticlericalism In The Nineteenth Century.” Journal Of Church And State. Vol. XII, No. 3 (Autumn 1970): 453-473.

[17] Waite, Arthur Edward. Devil-Worship In France. George Redway. London, England. (1896): 23-24.

[18] “The Real Lucifer” The Westminster Budget (London, England) February 21, 1896.

[19] Waite, Devil-Worship, (1896): 3-4.

[20] “Devil Worship” The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) September 13, 1896.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Novel About The Devil-Worshipers.” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) October 18, 1896.

[23] “Ibid.

[24] Sarah Bernhardt dans “Spiritisme”, comédie de Victorien Sardou : document iconographique. (1897) Spiritisme : comédie en 3 actes / de Victorien Sardou. – Paris : Théâtre de la Renaissance, 08-02-1897. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb39503290j. Bibliothèque nationale de France, 4-ICOPER-2369 (12.) Ark:/12148/btv1b8438732r.

[25] “Panic In The Opera House.” The New York Times (New York, New York) May 21, 1896.