William James, Harvard’s first professor of Psychology, was probably the most famous Theosophist from Cambridge, Massachusetts. (It was here where James operated a laboratory in “a small room [that] was given up to pickle jars and electric batteries.”)[1][2] For the sake of this article we’ll begin in the 1880s, a tumultuous time for James. The year of 1882 was bookended with the loss of his parents, beginning in January with the loss of his mother, Mary. In December, Henry James Sr. followed her in death.[3] This same year James’s godfather, Ralph Waldo Emerson (a personal hero to James) also died. James then went to Europe, where he was introduced to the ideas of Jean-Martin Charcot, France’s pre-eminent neurologist, and director of Salpêtrière Asylum (who was then conducting hypnotic experiments.) The lectures were given at Salpêtrière Asylum between 1883-1884.[4]] James returned to Harvard, but not before passing through England and meeting the founders of the newly formed Society for Psychical Research. Chief among them were Frederick Myers and Edmund Gurney.

William James. (Wiki)

James became a founding member of the American Society for Psychical Research (which convened out of the annual convention of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in September, 1884.) The first official meeting was held in January 1885 in the meeting rooms of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The membership was composed of distinguished physicians, scientists, and philosophers, primarily from Harvard and MIT.[5] James would continue to study psychical phenomena for the rest of his life, and conclude that “supernatural knowledge” was an established fact.[6]

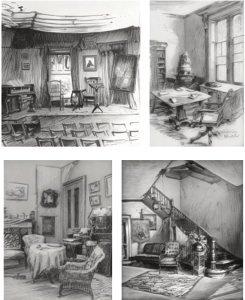

95 Irving Street, Cambridge Massachusetts c. 1888-1889.[7]

In 1889, the year of the first International Congress of Psychology, James moved to 95 Irving Street, in the Shady Hill neighborhood of Cambridge.[8] He also joined the parent group of the Society for Psychical research, and would go on “ghost hunts” in the environs of Boston equipped with an instrument of his own invention called a “thanatophantasmagorical indicator.”[9] According to James, the device was calculated to notify the observer of the presence of a ghost within a radius of 100 yards.[10] All the while he was writing a primer for the field of psychology. In 1890 James published The Principles of Psychology, in which he writes: “The consciousness of Self involves a stream of thought […] Whatever other things are perceived to be associated with this feeling are deemed to form part of that me’s experience. This me is an empirical aggregate of things objectively known.”[11] W.Q. Judge, President of the American Section of the Theosophical Society, noted that James’s theory of “inner consciousness” was harmonic with Theosophical cosmology, stating:

Hypnotist experimenting in France prove enough of this to make the rest possible. A man is placed in hypnosis. He is told that when he awakens, he will say certain things. When aroused he remembers nothing that occurred, but he says all that he was told to say, not knowing why he should. The Frenchmen, and Professor William James, of Harvard, agree with them, take it to prove an inner consciousness, and that upon many planes. Others with equal reason argue it as indicating an aggregate of personalities. Theosophy knows what it is. It is various human experiences speaking singly from the real man.[12]

James officially joined the Theosophical Society in 1891, just weeks after the death of Blavatsky.[13] At the time of his joining, he was preparing what he called “hallucination blanks” to distribute among the graduating Harvard students who were “about to scatter all over [the] wide country,” to collect statistics “as to what proportion of persons in the community have seen a vision, heard a voice, or felt touch when no one was physically present to account for the phenomenon.”[14]

MARGUERITE L. GUILD & THE CAMBRIDGE BRANCH

The Cambridge T.S. was 64th chartered Branch, began on July 16, 1892, with three people, the smallest membership permitted to begin a Branch.[15] It held its first meetings at 44 Brattle Street before moving to 15 Hillard Street in late July 1892.[16] The President of the Cambridge Branch was Marguerite Loring Guild, a French teacher by trade. She was joined by her brother, Dana Guild, who both joined the Boston T.S. with her on December 4, 1890.[17] The third founder, Arthur Conger, was a Harvard student who joined the Society on the day the Cambridge T.S. charter was issued.[18] “Virtually an offshoot of the Boston T.S.,” the Cambridge T.S. was a transient body during its early years and met in many places in the Old Cambridge District.[19]

Massachusetts Avenue and Boylston Street. Cambridge, Massachusetts c. 1890s. (Source: Historic New England.)

On August 17, 1892, Louis T. Wade, the new President of the Malden Branch, addressed the public meeting of the Cambridge Branch on the topic of “Karma and Reincarnation.” Wade, it was said, brought his “early training among the Jesuits a breadth and depth of knowledge and keenness of understanding that make him exceedingly interesting as a speaker.”[20] The meetings then moved to 125 Mount Auburn in November 1892, where they remained for nearly a year.[21] In September 1893, meetings were removed to the home of Marguerite L. Guild, 16 Ash Street, where they continued to meet, with few exceptions.[22]

HARVARD

At the close of 1893, Harvard University would become the first institution of higher learning to host a branch of the Theosophical Society. The Harvard T. S. was chartered on November 25, 1893, with its eleven charter members all being Harvard students. [23] The branch was “largely due” to the efforts of the Theosophical lecturer, Claude F. Wright.[24] Arthur Conger writes: “[Wright] came to Boston and proposed a plan for organizing a Harvard Branch of the T.S. among the students. He got together six of us for an organizational meeting and made an application for a Charter. Mr. Judge was doubtful if anything would come of it, but he issued a Charter.”[25]

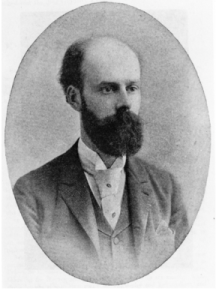

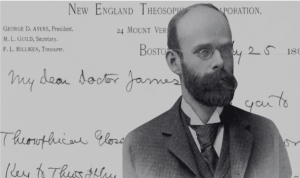

Claude Falls Wright (Source: Theosophy Wiki)

Claude Falls Wright, or “Ginger” as Blavatsky called him, because of the color of his hair, and his “unquenchable ‘pep.’” He was a small “wiry Irishman” of “much nervous energy, under perfect control, with a roving, gray-blue eye which has a piercing, thrust-like glance.” His “luminescent” hair (which he wore to his shoulders) and full beard were red as “certain Arctic lichens,” which contrasted with his “cream-tinted complexion in an unusually striking way.”[26] He was known for making a good first impression—and then shocking his new acquaintances with eccentricities (which many believed to be deliberate.) Some of these included eating no more than two meals a day, sleeping only a few hours a night, and working at his desk for eighteen hours at a time. His real genius was in organizing and public speaking, bringing to America the Theosophical Conversazione (a fixture in the London Headquarters) which became a fashionable feature of Branch activity in the United States.

Claude was the son of Alexander Falls Wright and Elizabeth Wright, who was the daughter of Lady Salkeld, May Ann Paine.[27] Having once been an enthusiastic member of the Young Men’s Christian Association at Christ Church, Leeson Park, Claude once considered a career in ministry.[28] He abandoned this idea after accepting the doctrines of reincarnation and karma. His next course of action was studying surgery at Dublin’s Royal College of Surgeons, but this idea, too, was abandoned. After Charles Johnston introduced him to Theosophy, he briefly had designs on studying for the Civil Service and moving to India.[29] Blavatsky convinced him to remain in Ireland, and revive the Dublin Branch after Charles Johnston left for India.[30] The Dublin Lodge arranged to hold their public meetings at 16 Charlemont Mall.[31] Claude officially joined the Theosophical Society on November 6, 1888, along with Alexander Weekes and Frederick Dick, and “Georgie” Johnston, the sister of Charles Johnston who was also his neighbor.[32] Not long after joining, Claude and Georgie became engaged. Georgie’s father, William Johnston, was not pleased, nor was Blavatsky.[33] While Johnston was in India, Blavatsky wrote “horrors and abominations” about Claude, and begged him to save Georgie. (Johnston even considered asking his mother-in-law if Georgie could stay with her in Russia.)[34] The question of what to do about Claude and Georgie appears to have been resolved through some intervention (divine or otherwise.) Evidently Claude was calling on an unnamed “young lady in Dublin one evening,” (possibly Georgie) when she suddenly “fell at his feet and went into a trance.” When the woman was revived, she told Claude that she had a message to deliver. “They” instructed her to tell Claude that “he was to go to Madame Blavatsky in London and work for Theosophy.” He packed at once.[35] Perhaps it was the Masters, perhaps it was a ruse to get Claude to leave, perhaps it was a way to save face for both parties, or, perhaps, it was none of these scenarios. Their engagement was broken off in August 1890.[36] Claude became a resident at Blavatsky’s London Headquarters, one of her personal secretaries, and a member of her Inner Group. He was by Blavatsky’s side at her death. “She died sitting her chair,” Claude states. “At the last she told me to go to America and work there and help William Q. Judge.”[37]

Claude went to America to assist the New York Branch, boarding in the home of the Brooklyn Theosophist, Lizzie Chapin.[38] Wright was one of the first Theosophical field lecturers who covered strategic points in the United States, with Judge acting as the “king-pin.” The lecturers would go to a city where Theosophy was beginning to be known. A Branch meeting was held in the afternoon, a public lecture in the evening, and often a visit to the editor of a local newspaper, in whose office the lecturer would write a report of said lecture. Before departing, a Branch of thirty or more members would be established. Wright also brought to America the Theosophical Conversazione, which was a fixture in the London Headquarters. It soon became a fashionable feature of Branch activity in the United States.[39]

LANMAN

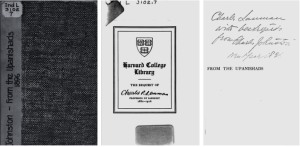

The Johnston’s possibly met the American Sanskritist, Charles Rockwell Lanman (1850-1941,) at this time, one of the two “friends and fellow workers,” whom Johnston dedicated his 1908 translation of the Bhagavad Gita and dedicated singularly his 1912 work The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[40] It is evident that the Johnstons knew Lanman on some personal level, and certainly by 1895. An inscription from Johnston to Lanman can be found in Lanman’s copy of Johnston’s From The Upanishads (1896): which reads: “Charles Lanman with best regards from Charles Johnston. New Year 1896.”[41] Lanman’s copy of From The Caves And Jungles Of Hindostan (1892,) contains a personal note from Vera Johnston: “To one lover of things of India from another—the translator, Vera Johnston.”[42] (Other Theosophical works in Lanman’s library included the 1897 edition of Claude Falls Wright’s An Outline Of The Principles Of Modern Theosophy.)

Lanman’s copy of From The Upanishads in Harvard Library.

A native of Norwich, Connecticut, Lanman received his education from Yale University, taking up Sanskrit under William Dwight Whitney. When Johns Hopkins University opened in Baltimore in 1876, Lanman accepted the position of Assistant Professor of Sanskrit. In 1880 Lanman joined the faculty of Harvard University, becoming the first to preside over the department of Indo-Iranian Languages.[43] 1884 saw the publication of the celebrated A Sanskrit Reader: With Vocabulary and Notes.[44] Together with Maurice Bloomfield (a fellow protégé of Sanskrit scholar, William Dwight Whitney,) Lanman would train nearly every Sanskrit professor teaching in American universities in the early twentieth-century.[45]

Charles Rockwell Lanman.[46]

Like Johnston, Lanman was a newlywed, having married his wife, Mary Billings Hinckley, in July 1888.[47] After sending a revised edition of A Sanskrit Reader to the printers in December 1888, Lanman and Mary set off for India.[48] On January 16, 1889, just around the time that the Johnstons were settling in at Murshidabad, Lanman was the “first representative of the flourishing school of American Orientalists” to visit the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.[49] During his time in India, Lanman would secure nearly 500 Sanskrit and Prakrit manuscripts for Harvard; texts which would form the nucleus of the college’s Sanskrit Library, and Harvard Oriental Series.[50]

Upon returning to America, Lanman would build a house in the Shady Hill neighborhood of Cambridge, adjacent to the homes of his friends, William James, and Josiah Royce. Both Lanman and James belonged to the Harvard History of Religions Club and were known to hold discussions on Indian philosophy.[51] Though Lanman does not appear to have joined the Theosophical Society like William James, it would seem that he was sympathetic to its aims.[52] During his tenure at Harvard Lanman would deliver lectures with titles like, “Theosophy, Transmigration, Karma, and Caste,” and give examination papers on the Upanishads, which he called “The Theosophy of India.”[53]

“WHAT PSYCHICAL RESEARCH HAS ACCOMPLISHED.”

A month after the formation of The Cambridge T.S., James’s essay “What Psychical Research Has Accomplished” was published in The Forum. “Another substantial bit of work based on personal observation is Mr. Hodgson’s report on Madame Blavatsky’s claims to physical mediumship,” James writes. “This is adverse to the lady’s pretensions; and although some of Madame Blavatsky’s friends make light of it, it is a stroke from which her reputation will not recover.”[54] A few months later, Charles Eliot, the President of Harvard, contributed his own essay to The Forum, “Wherein Popular Education Has Failed,” which was even less charitable to Theosophy:

No amount of [memoriter study] will protect one from believing in astrology, or theosophy, or free silver, or strikes, or boycotts, or in the persecution of Jews or of Mormons, or in the violent exclusion of non-union men from employment. One is fortified against the acceptance of unreasonable propositions only by skill in determining facts through observation and experience, by practice in comparing facts or groups of facts, and by the unvarying habit of questioning and verifying allegations, and of distinguishing between facts and inferences from facts, and between true cause and an antecedent event.[55]

Responding to competition from other universities, James persuaded the gifted German experimentalist, Hugo Münsterberg, to come to America and run Harvard’s laboratory of experimental psychology. Münsterberg had recognized the importance of popularizing the nascent science by publicly demarcating the “new psychology” from “psychical research.”[56]

CAMBRIDGE T.S. 1894

Holden Chapel.[57]

In February 1894, W.Q. Judge was in Boston in connection with the “housewarming” of the New England Theosophical Corporation, which opened its doors on 24 Mt. Vernon Street. On February 16, 1894, under the auspices of the Harvard Religious Union, Judge delivered a lecture, “The Underlying Basis of All Religions,” in Harvard’s Holden Chapel.[58] The President of the Harvard Religious Union was William Healy, who would become a “devoted member” of the Theosophical Society. Healy formally joined the Society just two weeks prior to Judge’s arrival.[59] A future pioneer in psychoanalysis, and criminology, who would one day establish the first child guidance clinic in America, Healy, at the time, was twenty-four-years-old, and had enrolled in Harvard in 1893 as a special student. He took several courses with William James, who became a personal friend and mentor to Healy.[60] Judge probably also met C.R. Lanman at this time.

Mt. Vernon Street & Joy Street.[61]

February 17, 1894 was the official “housewarming” of the New England Theosophical Corporation on Mt. Vernon Street. Judge was received by George D. Ayers, Robert Crosbie, and M.L. Guild, presidents, respectively, of the Malden, Boston, and Cambridge Branches.[62]

Interior of the New England Theosophical Corporation, 24 Mt. Vernon Street.[63]

On the afternoon of February 18, 1894, Judge delivered a nearly hour-long lecture titled “The Masters of Wisdom,” for the Cambridge T.S. on the first floor in Alden and Harlow’s new building, Brattle Hall.

Brattle Hall.

There was a large attendance, the floor was almost entirely filled, and the gallery partly-filled. “About three hundred persons,” were in attendance, with “many being Cambridge professors,” one of whom being William James.[64] During the talk Judge explained the nature of the Mahatmas:

The Mahatmas claim that Christ, Buddha, and Krishna, were all of their order, and in the same lodge, too, for their teachings in ethics are exactly the same. These ‘Masters’ do not come out to teach simply because they are too advanced for ordinary people. We do not send children to Harvard college, but we give them a foundation first. The Mahatma’s theory is that all men will eventually become perfect, and thus all will be masters and adepts and can do all these wonderful things. Has not Christ said, “All these things and greater than these shall ye do.” [65]

Guild closed the meeting by reading a chapter from The Golden Precepts. She then entertained a number of visitors at her home at 16 Ash Street.[66] Judge probably met Lanman at this time, and most certainly by the autumn of 1894. When embarking on the creation of The American Asiatic and Sanskrit Revival Society, Judge states: “For years America has had to depend upon European societies in the matter of Oriental research. The first break was made by Harvard College, where a private collection was started consisting of 1,000 manuscripts, 500 of which were contributed by Prof. Lanman.”[67] It is interesting to note that 16 Ash Street would one day be the home of Lanman’s future student, T.S. Eliot.[68] “Years spent in the study of Sanskrit under Charles Lanman, and a year in the mazes of Patanjali’s metaphysics under the guidance of James Woods,” Eliot states, “left me in a state of enlightened mystification.”[69] The Harvard T.S. would ultimately survive only a single year before the charter was canceled, and its members were absorbed into the Cambridge T.S.

Sarah Farmer & Greenacre.

The summer of 1894 saw another development within the broader milieu of the Theosophical movements, and that was the spiritual lecture series at Green Acre Inn, the summer resort for Boston intellectuals in Eliot, Maine. The host of the lectures, Sarah J. Farmer, was inspired to bring representatives from various philosophical traditions together during the time of the Parliament of World Religions, stating: “[I] always felt that I, too, was called, and that Green Acre had a part in the great work of Unification.” George D. Ayers, Sarah Bull, and Swami Vivekananda were among the first lecturers.[70] A week before Ayers spoke at Greenacre, he replied to a letter from James who consulted Ayers for insight into the Theosophical understanding of “personality,” while writing his entry, “Person and Personality,” in Johnson’s Universal Cyclopedia (1895.)[71]

Letter From Ayers to William James.[72]

THEOSOPHICAL HALL

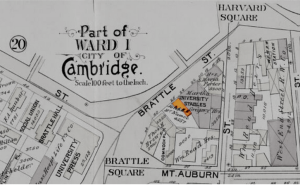

Harvard Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In the winter of 1895, the Malden Branch began a special movement “to bring Theosophy in plain and simple language to the so-called common and working people.” Meetings were held every Saturday evening under the charge of Harvey F. Burr which were managed differently from the regular Sunday public meetings. The subjects of discussion, announced in advance, were used with ten minutes allowed to each speaker after which a member of the Theosophical Society would sum up and close the discussion at greater length. On February 2, 1895, Marguerite Guild (President Cambridge T.S.) opened with the discussion, “Does Theosophy Offer a Reasonable Hope to the World’s Toilers?” It was expected that these meetings would “act as a feeder to the Malden Branch” and would include as much “newspaper work” as could be accomplished.

Harvard Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts.[73] (The spot highlighted in orange is 26 Brattle Street)

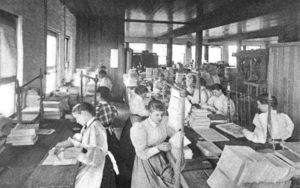

The Cambridge Branch attempted the same idea regarding workingmen as had the Malden Branch. On January 24, 1895, Guild wrote a letter to W.Q. Judge in which she explained her plans, as well as notifying him about the new space they recently acquired for the Cambridge T.S., the formal opening occurring the day her talk at the Malden Branch.[74] The lease they secured for permanent their meetings was at 26 Brattle Street, in “the finest building in Cambridge,” within a business block near Harvard Square.[75] “Its central location as well as the name over the front door,” it was said, “must assure all of the open and public nature of the meetings held there, and that exclusiveness can have no place in such a society.”[76] The influential Cantabrigian book-binder, J. H. H. McNamee, developed a block-addition to Brattle Street for his new four-story building. It was built with the of best brick, had a substantial iron front, with buff brick columns. Over the door of the building has been placed the sign “Theosophical Hall.”[77] One of the principal attractions of the building was the large marble entrance at the center which had a marble stairway that ascended to the second floor. On either side of the main entrance on the ground floor, were two large and “pleasantly lighted” stores. McNamee had his office on the second floor, as well as several handsome rooms for rental, with numerous ante-rooms, and closets for the use of the tenants. It was here, at the rear of the second floor, in a large room capable of seating 200 persons, where the Cambridge Theosophical Society held their meetings. The entire third floor was the printing office, and on the fourth floor the extensive book-binding business which was conducted. The fine building was furnished with the newest amenities, being one of the first in Cambridge to have an elevator.[78]

Women working at McNamee’s Bookbindery. 1895.[79]

The many windows were hung with striped burlap, tied back with heavy rope whose ends were fringed out into huge tassels. The light brown hangings of the speaker’s room drew out much admiring comment by their golden sheen, but their material was only jute. And the same sturdy fabric formed the body of the large heavy rug that covered the platform. (The cushions on the two cozy seats at the end of the hall near the library were covered with the same material.) The result was an unusually artistic room especially suited to its purpose, while at the same time lending it a reposeful ambience that was rarely found in a public hall.

McNamee’s Building. 26 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts. C. 1895.[80]

Guild began with a reading from I Corinthians. Minnie Hazleton Wade, “a tiny and charming bit of motherly femininity,” then gave a fifteen minute address on “Brotherhood as Found in the Teachings of Jesus.” Minnie was a prominent Boston member, and one of the most devoted Theosophists in the Society.[81] Burcham Harding, the lecturer for the Society in New England, followed with a talk on “Immortality,” stating that it can only be learned after successive reincarnations. Robert Chandler, formerly of the Aryan T.S., read passages from the Bhagavat Gita, commenting as he read, and showing that the Orient had realized, better than the West, that “humanity needs different forms of religion to accord with the differences in its mental, moral and political advancement.” William Healy then gave a sketch of the life and teachings of Buddha, showing how brotherhood had been preached and lived by that great teacher. Selections were then read from The Book of the Golden Precepts. Ayers gave the final address, on “Brotherhood In Theosophy.”[82] Guild responded with a verse from the Yajur Veda. “In him who knows that all spiritual beings are the tame in kind with the Supreme Being what room can there lie for sorrow and what for delusion, when he reflects upon the unity of Spirit.”[83] Not long after the meeting, Guild received a congratulatory letter from Judge, which contained his solicited advice:

There is a member of the Boston Branch who has always had a liking towards various efforts amongst the poorer people, whether it be in soup kitchens or what not. And if that could, be added through his aid to the matter it would be well. I do not pretend yet to know the proper plan to pursue, but I know that in general the object should be to simplify Theosophy as much as possible and to gain attention from the class of people I have referred to. I do think, however, that connections and affiliations directly with so-called labor organizations ought to be avoided, and that our efforts should be entirely on our own lines. It will, indeed, be a delightful thing if Boston should be the first to show useful results in this direction. It is the mass of the world indeed that needs our assistance, and if it does not get it the intellectual class to which we belong will not be able to save things in any general crash which might occur; and we all have to wait until the very least of us are raised up higher.[84]

VIVEKANANDA

In the spirit of “psychical research” it is, perhaps, worth mentioning a curious incident which occurred in the summer of 1895. It seems that Judge was in communication with someone referred to as “Omega.” Judge writes: “Have you yet received from me ‘Omega’s’ paper?”[85] After James died, it was alleged that his spirit used the symbol of “Omega” to circumvent the claims of fraudulent spirit-mediums: “He gave the Greek letter Omega as his sign and stated that it would always accompany his signature.”[86] In the same letter referencing “Omega,” Judge writes: “I hear that Sturdy brought over Vivekananda to London from here—and the sly fellow is now smashing at Theosophy.” E.T. Sturdy was a former-member of the Esoteric Section of Theosophy, who befriended Vivekananda, and, as the letter states, helped facilitate his arrival in America.[87] As Judge stated, Vivekananda was less than supportive of Theosophy, but his attention appears to have been focused on Annie Besant. In a letter to one of his followers at this time, Vivekananda writes:

Any suspicion of my connection with the Theosophists will spoil my work both in America and England, and well it may. They are thought by all people of sound mind to be wrong, and true it is that they are held so, and you know it full well […] I do not want to quarrel with the Theosophists, but my position is entirely ignoring them.[88]

In March 1896, James and Lanman would attend Vivekananda’s lecture at Sarah Bull’s Studio House, 168 Brattle Street.[89] Later that week, James hosted Vivekananda at his home on Irving Street, and they “were much interested in each other.”[90] Days later James would deliver his lecture, “The Will To Believe,” before Yale’s Philosophical Club at Osborn Hall.[91] “The greatest empiricists among us are only empiricists on reflection,” said James, “when left to their instincts, they dogmatize like infallible popes.”[92]

Sara Chapman Bull & Vivekananda. (Conference Room.)

PSYCHOLOGY CONGRESS

In August 1896 the Fifth Congress of Psychology was held in Munich, Germany. It was clear that the materialist faction of psychology was beginning to eclipse the “psychical” researchers whose work had informed much of the emerging field.[93] In a self-conscious effort to be regarded as a reputable science, leaders in the field of psychology were proactively distancing themselves from the more charismatic elements that were prevalent in the beginning. Dr. Carl Stumpf, president of the 1896 congress confessed: “I endeavored to prevent hypnotic and occult phenomena from occupying the foreground, as had been the case in former sessions.”[94]

Program for the Psychology Congress.

Though James was a member of the organizing committee of the Congress, he did not participate in it. There is a Theosophical connection here, though. Two Theosophists in attendance at the 1896 Congress, Franz Hartmann, and Karl Kellner, an inventor, occultist, and one of the wealthiest industrialists of the Habsburg Monarch. In the 1890s, Kellner’s business life merged with his and his occultism when he formed a co-operation with the Hartmann who had developed a cure-treatment for respiratory disease using the byproduct from the cellulose manufacture in Kellner’s paper plants. Kellner and Hartmann opened the “Inhalatorium” in Hallein in 1894 with Hartmann as director, and both men would later establish the Ordo Templi Orientis of Aleister Crowley fame. While there, they delivered a lecture on Samadhi with an Indian Yogi named Sen Bheema Pratapa.[95] “[Pratapa] went into the Samadhi sleep for the purpose of exhibiting that state before these professors and scientists so as to attract their attention to the existence of a state of higher consciousness,” Hartmann writes, “during which the body is insensible to pains inflicted upon it.”[96] Hartmann continues: “What appeared to be most strange to the scientists assembled, was that there was no symptom of any bodily disease discoverable. There was no sign of any cataleptic conditions, nor could the sleeping person be made to act upon any hypnotic suggestion.”[97] Kellner would produce a tract detailing Pratapas’s experience titled: Yoga: A Sketch of the Psychophysiological Part of the Ancient Indian Yoga Teaching. Not long after, an unidentified person who knew about James’s interest in yoga, sent him a copy of Kellner’s tract.[98] This tract, in turn, would find its way into James’s Varieties Of Religious Experience (1902):

A European witness, after carefully comparing the results of Yoga with those of the hypnotic or dreamy states artificially producible by us, says: “It makes of its true disciples good healthy and happy men […] Through the mastery which the yogi attains over his thoughts and his body, he grows into a “character.” By the subjection of his impulses and propensities to his will and the fixing of the latter upon the ideal of goodness, he becomes a personality hard to influence by others, and thus almost the opposite of what we usually imagine a “medium” so-called, or psychic subject to be.[99]

If I had to make a guess as to who sent James the copy of Kellner’s tract, Charles Johnston seems a likely candidate. In March 1896, William Quan Judge had died. The American Theosophists organized a world-wide Crusade in the summer of that year. Among those in the small party who accompanied the new President, Ernest Temple Hargrove on the trip, was Claude Falls Wright. A month after the 1896 Psychology Congress, the “Crusaders” were in Ireland, where they met up with Wright’s old friend, Charles Johnston.[100] Johnston met Kellner and Hartmann in 1888, and stayed in the “Inhalatorium” with those two men in the winter of 1893.[101] “I was then […] in the Austrian Alps, seeking, amid the warm scented breath of the pine woods and the many-coloured beauty of the flowers, to drive from my veins the lingering fever of the Ganges delta, and steeping myself in the lore of the Eastern wisdom,” Johnston writes.[102] The “Crusaders” subsequently made a stop at the “Inhalatorium” in September 1896 to meet Hartmann and Kellner.[103] At the urging of Griscom, Johnston would move to America in October 1896.[104] Perhaps Johnston gave a copy to Lanman or James himself, as he considered the man “one of Harvard’s most distinguished living sons.”[105]

CAMBRIDGE CONFERENCES

The Cambridge Conferences began in 1896 when invitation letters were sent to a selected number of Harvard professors, clergymen, divinity students, graduate and undergraduate students of Harvard and Radcliffe, and others interested in membership for conferences to be held for the “comparative study of ethics, religion, and philosophy during the six months from November, 1896, to May, 1897. ” Dr. Lewis G. Janes, of Brooklyn, President of the Ethical Association of New York, and lecturer for the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences’ School of Political Science, became the director of the “Cambridge Conferences.” Sara Bull would describe the need, and purpose, for the talks:—” The perception of a unity back of all, a human dependence on the Unsearchable was necessarily the final outcome to which each serious topic was reduced by means of the discussions lasting two hours and held on Monday evenings.”[106] It was the hub of Cambridge’s intelligentsia and artistic community, where Dharmapala, and Vivekananda spoke, and leading philosophers of Harvard, like William James, George Santayana, Josiah Royce, were regular guests.[107] (Ernest T. Hargrove would lecture in the Cambridge Conference in December 1900.)[108] In early 1897, the Cambridge T.S. had to leave McNamee’s building, and relocate to Raymond Hall (628 Massachusetts Avenue)[109] Guild writes:

Having thus practically moved to a new town, the Branch had much of its pioneer work to do again, and some members, reading of the success in other localities, had periods of discouragement at the smallness of their meetings.[110] This smallness was also brought about because the large class of people who kept attending meetings without ever joining the Society, were, that Winter, busy running after various Hindus of as many different persuasions, who have taken Old Cambridge and Harvard’s Psychology Department by storm. These good people are all too busy learning how to breathe to attend meetings which merely teach them how to do their duty.[111]

In 1897 Dharmapala was once again touring America.[112] He lectured at several American Branches throughout the country, including the Golden Gate Branch in San Francisco, and the Cincinnati Branch with Dr. J.D. Buck.[113] During this trip Dharmapala was briefly associated with the Ethico-Psychological School, “the first American School for the study of Buddhism.”[114] Joining him in this short-lived project was Myron W. Phelps, another Theosophist who belonged to the Aryan T.S. A lawyer by profession, and member of the Union League Club, Phelps joined the Society on June 10, 1890. Phelps, who briefly accompanied the “Crusaders” in 1896, would, upon his return, work with Katherine Tingley and E. Churchill Meyer, in their “Theosophical Colony” in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.[115] Sometime during the course of his travels, Dharmapala also met and developed a friendship with C.R. Lanman.[116] Before leaving the States, Dharmapala visited Greenacre in 1897, and lectured there for the first time.[117] (Johnston would follow in Dharmapala’s footsteps, and become a regular lecturer at Greenacre by 1902.)[118] At the time Greenacre was being hailed as a revival of the Concord School, but it was actually developing along similar lines as the Cambridge Conferences.[119]

SOURCES

[1] “Prof. William James.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts.) March 9, 1895.

[2] Taylor, Eugene. “William James and Depth Psychology.” Essay in The Varieties Of Religious Experience: Centenary Essays. Ferrari, Michel (ed.) Imprint Academic. Exeter, England. (2002): 11-36.

[3] Taylor, Eugene. “William James and Depth Psychology.” Essay in The Varieties Of Religious Experience: Centenary Essays. Ferrari, Michel (ed.) Imprint Academic. Exeter, England. (2002): 11-36.

[4] Taylor, Eugene. “William James and Depth Psychology.” Essay in The Varieties Of Religious Experience: Centenary Essays. Ferrari, Michel (ed.) Imprint Academic. Exeter, England. (2002): 11-36.

[5] “Nature Displayed.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) September 10, 1884; “American Society For Psychical Research.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts.) January 15, 1885; “List of Members and Associates.” Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research. Vol. I., No. 3. (December, 1887): 279-283.

[6] Ford, Marcus. “William James’s Psychical Research and its Philosophical Implications.” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. Vol. XXXIV, No. 3. (Summer, 1998): 605-626.

[7] Cogswell, Charles N. Cogswell Photograph Collection. Cambridge Historical Commission. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Collection ID: P014. (1883-1921)

[8] Cushman, Esther Lanman. “Where the Old Professors Lived.” The Proceedings Of The Cambridge Historical Society. Vol XLII. (1970-1972): 13-30.

[9] Taylor, Eugene. “William James and Depth Psychology.” Essay in The Varieties Of Religious Experience: Centenary Essays. Ferrari, Michel (ed.) Imprint Academic. Exeter, England. (2002): 11-36.

[10] “An Eastern Ghost Hunt.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) March 17, 1889; James, William. Essays In Psychical Research. Harvard University. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1986): 37-38.

[11] James, William. The Principles of Psychology Vol. I. MacMillan And Co. London, England. (1890): 158-160.

[12] “Devachan And Indra.” The Daily Inter-Ocean.(Chicago, Ill.) January 14, 1892; James, William. Psychology: Briefer Course. H. Holt. New York, NY. (1920): 200.

[13] [James & Theosophy] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7197. (website file: 1C: 1890-1894) Prof. William James (Joined 06/25/91.) For a more in depth exploration of James and the Theosophical Society in Boston see Leland, Kurt “Alarums and Excursions: William James and the Theosophical Society.” Theosophical History. Vol. XIX, No. 4 (October, 2018): 135-157.

[14] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) June 20, 1891.

[15] Judge, W.Q. “Mirror of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VII, No. 5. (August 1892): 165-172; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 9, 1895; “Theosophical Hall.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 9, 1895.

[16] Judge, W.Q. “Mirror of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VII, No. 6. (. (September 1892): 198-204; Jones, Edward A. Blue Book of Cambridge. Advertiser Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts (1895): 241.

[17] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6354. (website file: 1C:1890-1894); Marguerite Loring Guild. [12/4/1890]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6356. (website file: 1C:1890-1894); Dana Guild. [12/4/1890]; Cambridge, Massachusetts, City Directory (1892); Year: 1880; Census Place: New York City, New York, New York; Roll: 894; Page: 159B; Enumeration District: 569.

[18] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8325. (website file: 1C:1890-1894); Arthur Lantham Conger Jr.

[19] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) July 23, 1892; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) July 30, 1892.

[20] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) August 13, 1892.

[21] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) November 19, 1892.

[22] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) September 30, 1893; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 10, 1894; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 17, 1894.

[23] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8740. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) James Austin Wilder. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8741. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Cushing Stetson. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8742. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Henry A. Frothingham. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8743. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Warwick Potter. (11/18/93);

Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8744. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Arthur R. Weld. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8745. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Edward Motley Weld. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8746. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Charles Lowell Barlow. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8747. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Lawrence Mason Stockton. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8748. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Maynard Ladd. (11/18/93); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8749. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) George D. Whitehead. (11/18/93.)

[24] Judge, W.Q. “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. XII, No. 9. (December 1893): 297-299.

[25] Donant, Alan E. “Colonel Arthur L. Conger.” Theosophical History. Vol. VII, No. 1. (January 1998): 35-56.

[26] “Blavatsky’s Secretary Here.” The Indianapolis Journal. (Indianapolis, Indiana) April 15, 1893; “Theosophist Conclave.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) April 19, 1896.

[27] [Alexander Falls Wright] Place: Westminster, London, England; Collection: St James; -; Date Range: 1847-1853; Film Number: 1042322; {Elizabeth Adams]The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths Surrendered to the Non-Parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 5; Piece Number: 146; [Mary Ann Paine] Ancestry.com. England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.Mary Ann Pain was married to William Salkeld Adams.

[28] “Notes By The Way.” The Social Review. (Dublin, Ireland) August 8, 1896.

[29] “Faces Of Friends: Claude Falls Wright.” The Path. Vol. VIII No. 11. (February 1894): 351-352.

[30] “Stories Of Mme. Blavatsky.” The Kansas City Star. (Kansas City, Missouri) September 30, 1893; “The Theosophist Conclave.” The New York Tribune. (New York , New York) April 19, 1896.

[31] “The Dublin Lodge.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 15 (November 15, 1888): 246.

[32] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4654. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Charles Alexander Weekes; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4655. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Georgina Audley Hay Johnston; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4656. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Claude Falls Wright; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4657. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Frederick John Dick. [11/6/1888.]

[33] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [g.] March 4, 1889, Berhampur, India, entry; Guinness, Selina, “Ireland Through The Stereoscope: Reading The Cultural Politics Of Theosophy In The Irish Literary Revival” in Betsey Taylor FitzSimon and James H. Murphy (ed.,) The Irish Revival Reappraised. Four Courts Press. Dublin, Ireland (2004): 19-32.

[34] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [g.] September 14, 1889, Berhampur, India, entry.

[35] Claude provides three accounts of this event: (1) “[Blavatsky] wrote to me and asked that I come to London, and that she would teach me occultism. I determined to respond to her call. The night before I left, a friend of mine who was talking with me in a room, suddenly fell to the floor in a swoon. When he revived, he told me he had received a message from the Mahatmas to the effect that they had work for me to do. On the night following, this message was confirmed by Madame Blavatsky in London, where I had arrived. [“Stories Of Mme. Blavatsky.” The Kansas City Star. (Kansas City, Missouri) September 30, 1893.] (2) “One evening in Dublin, while in conversation with a lady, the latter suddenly fell into a trance, and said she had a message to deliver to Mr. Wright. She said ‘They’—whoever they were who were communicating through her—told her to say that he was needed to help in the work of the Theosophical Society. Mr. Wright thereupon packed up for London and called upon Mme. Blavatsky. [“Living Leaders Of Theosophy.” The World. (New York , New York) September 10, 1893.] (3) “He was calling on a young lady in Dublin one evening, when she suddenly fell at his feet and went into a trance. She said she had a message to deliver and that she was instructed to say that he was to go to Madame Blavatsky in London and work for Theosophy. He packed at once.” [“The Theosophist Conclave.” The New York Tribune. (New York , New York) April 19, 1896.]

[36] Yeats, William Butler. The Collected Letters Of W.B. Yeats: Vol. I 1865-1895. Edited by John Kelly and Eric Domville. Clarendon Press. Oxford, England. (1986): 212n10. (The editors mistakenly name Ada Johnston, not Georgie.)

[37] “With The Theosophists.” The Salt Lake Herald. (Salt Lake City, Utah) March 1, 1895.

[38] “Mirror of the Movement.” The Path. Vol. VI, No. 11 (February 1892): 361-368; New York, State Census, 1892.

[39] Wright, Leoline Leonard. “Recollections Of A Theosophical Speaker. Pt. I.” The Theosophical Forum. (September 1938); Wright, Leoline Leonard. “Recollections Of A Theosophical Speaker. Pt. IV.” The Theosophical Forum. (September 1939); Hargrove, E.T. “Letters From William Q. Judge: Pt. VI.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXX, No. 2 (October 1932): 122-129.

[40] Johnston, Charles. Bhagavad Gita: The Song of the Master. The Quarterly Book Department. New York, New York. (1908): Dedication; Johnston, Charles. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Charles Johnston. New York, New York. (1912): Dedication.

[41] Johnston, Charles. From The Upanishads. Whaley. Dublin, Ireland. (1896.)

[42] Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna; Johnston, Vera (tr.) From The Caves And Jungles Of Hindostan. Theosophical Publishing society. London England (1892): iii.

[43] “Sanskrit For Harvard.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 2, 1880.

[44] Lanman, Charles Rockwell. A Sanskrit Reader: With Vocabulary and Notes. Ginn, Heath, & Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1884):.

[45] Tull, Herman. “Whence Sanskrit? (Kutaḥ Saṃskṛtamiti): A Brief History of Sanskrit Pedagogy in the West.” The International Journal of Hindu Studies. Vol. XIX, No. 1/2 (April-August 2015): 213–256.

[46] Belvalkar, S. K. “In Memoriam C. R. Lanman.” Annals Of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. XXII, No. 3/4 (July-October 1941): 300-04.

[47] “Table Gossip.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts.) July 29, 1888; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1840–1911. New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915. New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[48] Lanman, Charles Rockwell. A Sanskrit Reader: With Vocabulary and Notes. Ginn, Heath, & Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1888): iii-x.

[49] “Professor Lanman On Oriental Studies In America.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts.) May 3, 1889.

[50] Belvalkar, S. K. “In Memoriam C. R. Lanman.” Annals Of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. XXII, No. 3/4 (July-October 1941): 300-04.

[51] Cushman, Esther Lanman. “Where the Old Professors Lived.” The Proceedings Of The Cambridge Historical Society. Vol XLII. (1970-1972): 13-30; Taylor, Eugene. William James On Consciousness Beyond The Margin. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey (2011): 62; Croce, Paul J. Young William James Thinking. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland (2018): 177.

[52] William James joined the Theosophical Society in 1891. [Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7197. (website file: 1C: 1890-1894) Prof. William James (Joined 06/25/91.)]

[53] “To Talk On Brahminism.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 27, 1925; J. “Emerson And Asia.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXVIII, No. 2 (October 1930): 202-204.

[54] James, William. What Psychical Research Has Accomplished. The Forum. Vol. XIII, No. 6. (August, 1892): 727-742.

[55] Eliot, Charles W. “Wherein Popular Education Has Failed.” The Forum. Vol. XIV, No. 4. (December 1892): 411-428.

[56] Sommer, Andreas. “Psychical Research and the Origins of American Psychology: Hugo Munsterberg, William James and Eusapia Palladino.” History of the Human Sciences. Vol. XXV, No. 2(2012: 23–44

[57] Hill, George Birbeck. Harvard College By An Oxonian. MacMillan And Co. New York, New York. (1894): 12.

[58] “University Organizations: Harvard Religious Union.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 16, 1894; “Lecture By W.R. Judge.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge), February 17, 1894.

[59] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 10627. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) William Healy; “Old Cambridge.” Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) May 12, 1894; “Officers of College Organizations.” The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine. Vol. III., No. 10. (December 1894): 254-257; “Old Cambridge.” Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts.) February 9, 1895.

[60] Bennett, James. Oral History and Delinquency: The Rhetoric of Criminology. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Il. (1988): 114; Snodgrass, Jon. “William Healy (1869-1963): Pioneer Child Psychiatrist And Criminologist.” The Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences. Vol. XX. (October 1984): 332-339.

[61] “View Of Mount Vernon Street, Looking Toward State House, Boston, Mass., 1902-1905.” Historic New England. DigitalID 001513. AccessID 2343. Other identifier HNEDID-001513. General photographic collection. PC001.02.01.USMA.0340.5770.002.

[62] “Theosophists At Home.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts.) February 18, 1894; “A House Warming.” The Boston Sunday Post. (Boston, Massachusetts.) February 18, 1894.

[63] “Boston Headquarters.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 22 (August 10, 1896): 5.

[64] Judge, W.Q. “Mirror of the Movement.” The Path. Vol. VIII No. 12. (March 1894): 439-442; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 17, 1894; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 17, 1894.

[65] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 24, 1894.

[66] Jones, Edward A. Blue Book Of Cambridge. Advertiser Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts (1895): 241.

[67] “To Seek Hindoo Manuscripts.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) December 17, 1894.

[68] Jones, Edward A. Blue Book Of Cambridge. Advertiser Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts (1895): 241.

[69] Crawford, Robert. Young Eliot: From St. Louis to The Waste Land. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. New York, New York. (2015): 173; Miller Jr., James E. T. S. Eliot: The Making of an American Poet, 1888–1922. Penn State Press. University Park, Pennsylvania. (2005): 172; Spurr, Barry. Anglo-Catholic In Religion: T.S. Eliot And Christianity. The Lutterworth Press. Cambridge, England. (2010): 5.

[70] “Vivekananda At Greenacre.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) July 28, 1894; Phelps, Myron H. “Green Acre.” The Word. Vol. I, No. 2 (November, 1904): 52-67.

[71] Higgins, Shawn “Archival Material: A Letter From George D. Ayers to William James.” Theosophical History. Vol. XIX No. 4. (October, 2018):132-133; James, William. “Person and Personality.” entry in Johnson’s Universal Cyclopedia. A.A. Johnson Company. New York, New York. (1895): 538-540.

[72] Higgins, Shawn “Archival Material: A Letter From George D. Ayers to William James.” Theosophical History. Vol. XIX No. 4. (October, 2018):132-133.

[73] G.W. Bromley & Co. Atlas of the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts :from actual surveys and official plans. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley and Co., (1894) Plates 16-20. Seq. 23. Harvard Map Collection. Harvard University. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl:1079558?n=23. Accessed 22 February 2024.

[74] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 12. (March 1895): 439-442.

[75] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. IX, No. 11 ((January 1895): 324-328; [75] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 12. (March 1895): 439-442; Donant, Alan E. “Colonel Arthur L. Conger.” Theosophical History. Vol. VII, No. 1. (January 1998): 35-56.

[76] “Theosophical Hall.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 9, 1895.

[77] “Mirror Of The Movement.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 12. (March 1895): 439-442.

[78] “In His Own Building.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) March 9, 1895.

[79] McNamee, John H.H. The Essentials of Good Binding: A Lecture Delivered Before the Massachusetts Library Club. Lombard & Caustic. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1896): 10.

[80] McNamee, John H.H. The Essentials of Good Binding: A Lecture Delivered Before the Massachusetts Library Club. Lombard & Caustic. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1896): 38.

[81] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6726. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Mary H. Wade. [61 James Street, Malden, Massachusetts. Malden T.S. (4/20/91); Wright, Leoline Leonard. “Recollections Of A Theosophical Speaker. Pt. IV.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. XIV. (September 1839.)

[82] Theosophists were likely exposed to this from Judge’s 1893 article, “A Commentary On The Gayatri.” [Judge, William Quan. “A Commentary On The Gayatri.” The Path. Vol. VII, No. 10 (January 1893): 301-303.

[83] “New Hall Opened.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 9, 1895; “Theosophical Hall.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 9, 1895.

[84] The letter in full states: “I have your letter of the 24th of January and am very glad to hear the news of your Branch taking the hall in Cambridge under such good auspices. Please tell the Branch how glad I am of this and hope they will be able to sustain it. But, anyway, if it should not be possible to make it permanent, the effort will be of great use and value. I think if every means possible are taken, with your lights and with your opportunities and other advantages, by the Branch, you can do a good deal towards trying to filter Theosophy down into other classes of society. Theosophy, to reach those other people, has to be made simple, so that it can be understood. This would mean that so much intellectual attention would not be devoted to recondite points. All foreign terms should be eliminated, and English substitutes obtained and used. This is possible in every case. I think you would have now and then to furnish these people with some kind of entertainment. I have never believed in that kind of Theosophy which refuses to have an amusement in any way attached to a meeting, for that is sometimes absolutely necessary in the way of either music or something else. I think leaflets could also be altered so as to be understood. In fact, my opinion is this, that unless, now that we have affected the entire thinking world with our theories, we succeed in getting hold of larger numbers of the so-called lower classes, we will end in failure, because it is too often the case that those who take up Theosophy now take it up intellectually, whereas it should be a matter of the heart. As it explains the whole of life it should explain everything, even to a poor person, though the initial difficulty in that ease is to get over their bad feelings. There is a member of the Boston Branch who has always had a liking towards various efforts amongst the poorer people, whether it be in soup kitchens or what. not. And if that could, be added through his aid to the matter it would be well. I do not pretend yet to know the proper plan to pursue, but I know that in general the object should be to simplify Theosophy as much as possible and to gain attention from the class of people I have referred to. I do think, however, that connections and affiliations directly with so-called labor organizations ought to be avoided, and that our efforts should be entirely on our own lines. It will, indeed, be a delightful thing if Boston should be the first to show useful results in this direction. It is the mass of the world indeed that needs our assistance, and if it does not get it the intellectual class to which we belong will not be able to save things in any general crash which might occur; and we all have to wait until the very least of us are raised up higher.” [Judge, William Q. “The Old And New.” Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 22 (November 16, 1896): 2.]

[85] Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXX, No. 3. (January 1933): 206-212.

[86] Mcfarlane, Peter Clark. “Spiritgrams.” Cosmopolitan. Vol. LVII, No. 3 (February, 1915): 254-256.

[87] Cleather, Alice Leighton. H. P. Blavatsky As I Knew Her. Thacker, Spink & Co. Calcutta, India. (1923): 23; Hargrove, Ernest Temple. “Letters From W.Q. Judge.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXX, No. 3. (January 1933): 206-212.

[88] Swami Vivekananda to Alasinga Perumal [January 23, 1896.] https://www.swamivivekananda.guru/2017/06/22/to-alasinga-perumal-9/

[89] “Death Of Mrs. Ole Bull.” Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) January 21, 1911; Taylor, Eugene. William James On Consciousness Beyond The Margin. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey (2011): 164-165.

[90] Burke, Marie Louise. Swami Vivekananda in the West: The World Teacher. Advaita Ashrama. Kolkata, India. (1983): 78.

[91] “Yale Notes. The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut) April 18,1896.

[92] James, William. “The Will To Believe.” The New World. Vol. V, No. 18. (June, 1896): 327-347.

[93] Penzig, Ottone. “Some Notes On The Fifth Congress Of Psychology.” The Theosophical Review. Vol. XXXVI, No. 215. (July 1905): 454-458; Sommer, Andreas. “Psychical Research and the Origins of American Psychology: Hugo Münsterberg, William James and Eusapia Palladino. History of the Human Sciences. Vol. XXV, No. 2. (2012): 23-44.

[94] Alvarado, Carlos S. “Telepathy, Mediumship, And Psychology: Psychical Research At The International Congresses Of Psychology, 1889–1905.” The Journal Of Scientific Exploration. Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (June 30, 2017): 255–292.

[95] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4214. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Dr. Carl Kellner. (10/26/87); “The Kellner-Partington Paper Pulp Company Limited.” The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. (Manchester, England) May 22, 1889; “Dr. Hartmann And His Works.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) April 23, 1897; Urban, Hugh. “The Yoga Of Sex: Tantra, Orientalism, And Sex Magic In The Ordo Templi Orientis.” Essay in Hidden Intercourse: Eros And Sexuality In The History Of Western Esotericism., edited by Wouter J. Hanegraaff and Jeffrey J. Kripal. Brill. Boston, Massachusetts (2008): 402-443; Baier, Karl. “Yoga Within Viennese Occultism: Carl Kellner and Co.” Essay in Yoga in Transformation. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Karl Baier, Philipp A. Maas, and Karin Preisendanz. Vienna University Press. Vienna, Austria (2018): 389–438.

[96] Hartmann, Franz. “An Indian Yogi Before A Tribunal Of European Psychologists.” Theosophy. Vol. XII, No. 3 (June 1897): 89-91.

[97] Hartmann, Franz. “A Yogi In Europe.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 4 (October, 1896): 461-462.

[98] Baier, Karl. “Yoga Within Viennese Occultism: Carl Kellner and Co.” Essay. In Yoga in Transformation. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Karl Baier, Philipp A. Maas, and Karin Preisendanz. Vienna University Press. Vienna, Austria (2018): 389–438.

[99] James, William. The Varieties Of Religious Experience. Longmans, Green, And Co. New York, New York. (1902): 401 n.

[100] Johnston, Charles. “American Crusaders.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) September 6, 1896.

[101] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [g.] December 1893, Hotel Stern, Hallein. Salzburg, Austria, entry.

[102] Duessen, Paul; Johnston, Charles (tr.) The System Of The Vedanta. The Open Court Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1912): v-vi.

[103] H.T.P. “The Stop At Interlaken” The Theosophical News Vol. I No. 16 (October 5, 1896): 1-3; E.T.H. “The Screen of Time.” Theosophy. XI, No. 7 (October 1896): 193-198; “The Crusade.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. II, No. 6 (October 1896): 95-95; “The Crusade.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. II, No. 7 (November 1896): 110-112.

[104] On October 19 and October 21, just before these talks, Dewey dined with Montague. On October 23 Dewey went to Englewood, New Jersey, (presumably accompanying Montague to Upton Sinclair’s new Helicon Home Colony. On October 20, 1906, Percy Grant was called to Brookline, Massachusetts, by the sudden death of his father, Stephen M. Grant, a prominent merchant of Boston. He remained there until after the funeral on October 22. The first meeting likely occurred on October 24, 1906. [Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.]

[105] Johnston, Charles. “Notes And Comments.” The Theosophical Quarterly. VII, No. 2. (October 1909): 105-112.

[106] Mrs. Ole Bull. “The Cambridge Conferences.” The Outlook. Vol. LVI, No. 15. (August 1, 1897): 845-849.

[107] “Death Of Mrs. Ole Bull.” Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) January 21, 1911.

[108] “Amusements.” The Boston Evening Transcript (Boston, Massachusetts) December 8, 1900; “Lecture At Studio House.” The Cambridge Chronicle (Cambridge, Massachusetts) December 15, 1900.

[109] “Cambridgeport.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) October 24, 1896); Weston’s Guidebook And Street Directory of Cambridge. L.F. Weston. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1899): 25.

[110] The Cambridge T.S. moved to Raymond Hall, 628 Massachusetts Avenue. “Cambridgeport.” The Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, Massachusetts) October 24, 1896; Weston’s Guidebook And Street Directory of Cambridge. L.F. Weston. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1899): 25.

[111] “Cambridge (Mass.) T.S.” Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 31 (January 18, 1897): 3-4.

[112] Kemper, Steven. Rescued From The Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala And The Buddhist World. University Of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2015): 449; “Colonel Olcott At Home.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI., No. 10. (February, 1901): 182-188; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 68.

[113] “The Noted Buddhist.” The Cincinnati Enquirer. (Cincinnati, Ohio) December 7, 1896; “Will Spread The Light Of Asia.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) February 25, 1897.

[114] “Ethico-Psychological School.” The Nebraska State Journal. (Lincoln, Nebraska) July 13, 1897; Kemper, Steven. Rescued From The Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala And The Buddhist World. University Of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2015): 396-397.

[115] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6042. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Myron H. Phelps. The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists.; Class: BT26; Piece: 97; Anon. “Our Illustration.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I No. 10. (August 24, 1896): 3; “A Brotherhood Supper.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) October 1, 1896; Phelps, Myron H. Life And Teachings Of Abbas Effendi. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1903); Phelps, Myron H. “Green Acre.” The Word. Vol. I, No. 2 (November, 1904): 52-67.

“Useless To Rebel Now.” The Calgary Herald. (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) July 4, 1908; “Converts Are Not Genuine.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) August 16, 1908; Ganachari, Aravind Gururao. “Myron H. Phelps (1856-1916): An Early American Advocate Of India’s Freedom.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. LII (1991): 650-657.

[116] Pierce, Lori. “Buddhist Modernism In English-Language Buddhist Periodicals” in Issei Buddhism In The Americas. (eds.) Williams, Duncan Ryuken; Moriya, Tomoe. University Of Illinois Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2010): 87-109.

[117] “The Greenacre Lectures.” Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) August 14, 1897; “The Humors Of Greenacre.” Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 11, 1897.

[118] “Greenacre Conference.” The Bangor Daily News.(Bangor, Maine) July 1, 1902; Phelps, Myron H. “Green Acre.” The Word. Vol. I, No. 2 (November, 1904): 52-67; Johnston, Charles. “Immigrants And Music.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XLVII, No. 2446 (November 7, 1903): 1801.

[119] Cameron, Kenneth Walter. Transcendentalists in Transition: Popularization of Emerson, Thoreau, and the Concord School of Philosophy in the Greenacre Summer Conferences and the Montsalvat School (1894-1909.) Transcendental Books. Hartford, Connecticut. (1980): 135-136, 151.