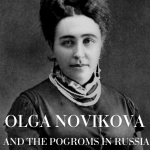

Marie Sinclair. (wiki)

Marie Sinclair (1830-1895) was the only surviving daughter of Don José de Mariategui, of Santa Catalina, the dealer of precious gems, by which “she came in possession of […] marvelous jewels which [were] the wonder of all Europe.”[1] From an early age Marie was interested in occult subjects, beginning with Mesmerism and Clairvoyance, and later gravitating toward Spiritualism.[2] In 1853 she married General Conde de Medina Pomar, with whom she had one child, a devoted son named Emmanuel, who “was ever by his mother’s side.”[3] When de Medina de Pomar died in 1868, Marie inherited a sizable fortune.[4] Not long after his death, Marie and Emmanuel began attending séances with the Scottish Spirit-Medium, Daniel Dunglas Home.[5] (Emmanuel shared his mother’s interest in occultism, and both would contribute to metaphysical literature for the remainder of their lives.)[6] Describing one séance in 1869, Marie writes:

There was a great deal of light in the room; two gas lights burning low, and lighted candles on the chimney of both drawing-rooms. An exact imitation was given by rappings and by the heaving of the table, of a railway train; no one could doubt what was meant, it was so perfectly imitated […] He asked the spirit if he were really Rossini, to play something from one of his operas, and the accordion immediately played the overture to ) William Tell.[7]

In 1872 Marie married James Sinclair, the 14th Earl of Caithness, a man “well-known for his mechanical inventions.”[8] A few days after her marriage, she went to an old castle, which formerly belonged to Mary Stuart, the Queen of Scots, but was now her property. While there, Marie saw “the phantom of [Mary Stuart] pass over the tombs of the Caithness family chapel. At first, she could not believe her eyes, but a subsequent event convinced her of the reality of the spectral presence.[9] It was said: “One day, the gentle voice which spoke within her, ordered her to go at midnight to the Chapel of Holyrood at Edinburgh.”[10] Marie states:

My midnight visit to Holyrood was made on an intensely dark night. The brightness of the stars above only served to make the darkness more visible. Never, never, I thought, could this once lovely chapel have looked more beautiful than it did at the moment,” lighted alone by the stars of heaven, that looked in upon me from all sides through the Gothic windows, and from the deep blue of the canopy that was my only roof, and their vast dwelling place. Thus thinking. I reached the glorious Eastern window, where the high altar once stood, but which now looks down upon the green grass and a few broken stones. On one of these I knelt, “and lifting my thoughts to Heaven, prayed fervently for my sweet guardian who had once knelt on this very spot, decked in all the bravery of a bride, to plight her troth to the handsome Darnley.” “His grave now stood ” close at my right hand, and that of poor murdered David Rizzio I had passed near the door. “Where are they all now, where are you, my ever beautiful,” “precious Marie?” “Here, with you,” said a voice, and as I turned, I saw a faint and shadowy form, more like a cloud or mist than a living being, but which soon assumed a more tangible appearance. “You see I have kept my word,” she said, and from that moment she commenced and poured out the most sublime and glorious address I have ever heard.[11]

It was around this time that “Lady Caithness believed herself to be in possession of the soul of Marie Stuart, and regulated her life, as far as possible, on the tastes and inclinations she believed Marie Stuart to have possessed.”[12] In 1873 Marie and James visited the United States, where they toured Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other cities.[13] In April 1873, while in Boston, they were given a tour of Harvard University by Louis Agassiz, the esteemed zoologist who was infamous in the Spiritualist community.[14] In 1857 a student named Frederick L.H. Willis was expelled from Harvard Divinity School for acting as a Spirit-Medium.[15] Agassiz was appointed to the committee to investigate Willis’s claims. A book published in 1874 by Allen Putman would suggest that Agassiz actually had Spiritualist sympathies, thus revising the whole affair for a new generation.[16] Caithness herself would question Agassiz on his views on Spiritualism, to which he would state: “We are indeed forced to admit that the gradations which mark the great and gradual progression of all created things and which unites all animals is an intellectual and not a material one.”[17] Marie soon developed a friendship with the American Spiritualist, Emma Hardinge Britten.[18] She also developed an interested in the Spirit-Medium named Cora Richmond.[19] Marie would return to America again in in 1876, to attend Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[20] It was the innaugural year of the Theosophical Society, of which Britten (along with Blavatsky, Colonel Olcott, and W.Q. Judge,) was a founding member.[21] Marie, no doubt, was made aware of the Society at this time by Britten, and most certainly by 1877.[22] In June 1876, almost as soon as she returned to Europe, she contacted Anna C. Kimball, who was then hosting her “Star Circles” in London.[23]

ANNA KIMBALL

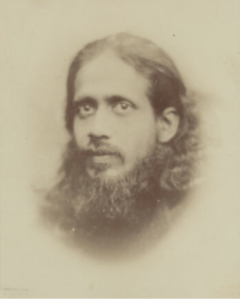

Anna Kimball.[24]

Anna Kimball (1827-1920) was born Chautauqua County, New York.[25] The niece of the early Mormon leader, Heber C. Kimball, Kimball followed the path of Spiritualism, and was quite popular in that movement, even campaigning in Victoria Woodhull’s Equal Rights Party in 1872.[26] “I was a somnambulist from my earliest remembrance,” Kimball would state. “[I] awoke often in the night standing in the dark, conscious of having had ‘such a lark’ with invisible children.” These spirit-children, Kimball would claim, endowed her with special knowledge. “I could see evil, disease and false hood as through a glass in all natures.”[27] Kimball adds:

When about twelve years of age, I learned that I could, at will, induce clairvoyance or that clear-seeing state, wherein I could see the soul of all things. Secret things seemed clear to me at those hours and memory quickened. I frequently recalled scenes and experiences of former lives. I saw a sweet and most tender soul-mother and father in that all radiant Inner land, who seemed then and now to have been my parents from eternity. They lived in a world of perfect peace and indescribable beauty, a land as real and objective as this. It was during these visits to that inner world, that I received most of my knowledge and training in psychometry [the ability to “read” the history of an object or person by their subtle vibratory emanations,] in schools in which everything was imparted through this intuitive faculty.[28]

As a practitioner of psychometry , Kimball’s most notable reading was conducted on a fragment of a meteorite given to her by William Denton (the inventor of the term psychometry.) She divined from this meteorite the story of the doomed planet of Sideros. The inhabitants of that former planet once freely communicated with the spirits. In a revelation that likely sent a shiver down the spines of the opponents of Free Love, the denizens of Sideros also had sexual relations with the spirits, and had children with them.[29] For Kimball, a New Age was approaching when Earthlings, like the Siderians, would have sexual intercourse with spirit lovers.[30] In November 1875, Kimballs spirit guides directed her to leave for England, and carry out their wishes.

In London a number of Mediums under development and workers interested in the cause, made applications to form an “agreeable company.” On March 13, 1876, the first meeting of the “Star Circle” was held. The seats were arranged in a circle around the rooms, with an open space in the middle where a smaller space was formed by Mediums who had previously sat with Kimball. When Kimball entered the room, her Control (spirit-guide) directed that the larger outer circle be terminated on either side of the folding doors, and the inner circle be arranged along similar lines. Kimball took her seat at in the open doorway, at the “pole” of the “double horseshoe.” At this juncture, the spirit of Mary Queen of Scots took possession of Kimball, who was transformed under “spirit influence.”[31] It was this communication with Mary Stuart that prompted Marie to invite Kimball to Edinburgh.[32] Marie writes:

The Marie who spoke was the Marie of the “Star Circle,” of which she had before declared to me she was one of the messengers,—a circle of pure, great, and holy ones, whose most earnest eendeavor is to unite man to God, to bring Heaven nearer to earth.” “She stated that representative spirits from all times and all nations of the earth have organized in the form of a star.” “ This glorious circle inaugurated on earth under the simple title ‘Star Circle’ is the Christ Circle.”[33]

Marie, however, still held space for the broader esoteric movements. After the publication of Isis Unveiled (1877) Marie wrote a letter to Madame Blavatsky “offering her friendship, and inviting [Blavatsky] to pay her a visit on our way out to India.”[34]

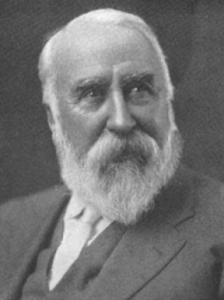

Edward Maitland (wiki)

Anna Kingsford (wiki)

In September 1878, Edward Maitland, a Medium who specialized in automatic-writing, met Emmanuel (Duc de Pomar.) Emmanuel was then introduced to Anna Bonus Kingsford, Maitland’s (non-romantic) partner. She was the wife of a clergyman, and about to embark on a medical degree in Paris. Kingsford was also a Medium, and received her “illuminations” while sleeping (or when sedated with chloroform.) Both Maitland and Kingsford studied Hermetic philosophy from material collected in the British Museum, and their hermeneutics of Christianity was ahistorical, favoring an esoteric view of those doctrines. Emmanuel then introduced Maitland and Kingsford to Marie, who loaned the duo books by Jacob Boehme and Eliphas Lévi. Marie was impressed with both of them, and believed that Kingsford, an “inspired Pythoness” had an important role to play in the “New Dispensation dawning.” Their spirit guides permitted them to reveal to Marie some of their prophetic revelations concerning the coming feminine Messiah, said to occur in 1881. Marie, meanwhile, separated from James in 1879, the same year that Pope Leo XIII extended to her by letters patent the title and rank of Duchesse de Pomar. [35] (Already in 1875, when Emmanuel came of age, he was created Duke de Pomar by the Pope.) Marie Sinclair thus held the titles Countess of Caithness, and Duchess of Pomar, but presumably owing to her separation, preferred the title of Duchess of Pomar.[36] In 1880 Marie moved to Paris, taking an apartment at 51, rue de l’Université. Despite the Pope’s honorific conferral, Marie’s relationship with the Church was less than orthodox. Marie writes:

The French are not a religious people. If they were they would see the errors of the church but occupied with mundane things, they do as the church bids them. Secretly many priests are interested in Theosophy. They frequently visit me. You asked me if I ever communed with the spirits. I have sat in this very room when the air was as thick with spirits as a sunbeam with motes. I recollect one occasion particularly […] when the spirits spoke so distinctly that I asked my visitor if he did not hear them. He was a young Catholic priest who had just finished reading to me a letter that he had written to the Pope explaining that the masses were becoming so enlightened, so interested in occult sciences, that it will soon be impossible for the Church to conceal truth as it has in the past, and urging upon the holy father the necessity of establishing a journal at Paris for the elucidation of these truths and queries. [The Pope did not respond] and I knew he would not, for while the priest read the letter the spirit said as distinctly as I repeat it to you: “The Pope has no power. It rests with a woman.”[37]

In August 1879, Kingsford wrote to Caithness stating: “With regard to the Pope, after much reflection I have decided to postpone my letter to him, until my apprenticeship at the Faculté being at an end—I may say what I have to say without fear, and may have the weight of my degree to add authority to my representations.”[38]

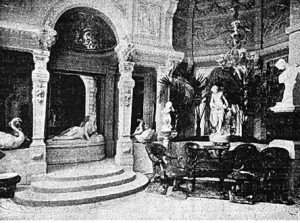

The Earl of Caithness died in New York on March 27 1881. Marie’s widow’s weeds were exact replicas copied from pictures of Mary Stuart. “The black cap, pointed on the forehead, and swelling out over the temples, was not chosen from coquetry, but from sympathy with the ill-starred Scottish Queen, whose spirit ever haunts all rooms inhabited by her ladyship.”[39] She rented the whole first floor and garden of one of the stateliest mansions, the Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, and acquired the exclusive use of the grand hall and stairs. This brownstone castle, located at the corner of l’avenue de Wagram and le Rue Brémontier, was in Fauborg St. Germain, “the old and aristocratic quarter of the city.” It had six drawing-rooms, a ball-room, a dining room, boudoir, and a master bedroom belonging to Marie. She began making extensive renovations, until it became a perfect facsimile of Renaissance architecture. Every room was “decorated in exquisite taste, representing millions of francs, [and had a] souvenir of Marie Stuart.” Maris called this estate “Holyrood” in honor of Mary Stuart, and it was said that “Lady Caithness’s own bedroom [was] crowded with portraits of this unhappy Queen. They [covered] every available space, and the collection in itself is of priceless historical value.”[40] She only received guests “in a very quiet and intimate way,” and for a companion, she had “a little black and tan dog” that was “always on her train” when she walked or sat down, “and running after her when she moves.”[41]

Vestibule of Hôtel de Pomar.[42]

Marie then ordered a marble statue of Mary Stuart from the sculptor Ringhel, and offered it to the city of Paris “on the condition that it should be placed in one of the public squares.” After a long (and animated) discussion, the Municipal Committee of Paris agreed to accept the statue, provided that it was placed in a museum. “Very well,” replied Marie, “I withdraw my offer, and I shall give my Queen in marble to the town of Edinburgh, which will know how to do honor to it.”[43]

Maitland and Kingsford’s “illuminations” had culminated in the work, The Perfect Way, published early in 1882. It was then that Marie urged Maitland and Kingsford consider the Theosophical Society, confessing her belief in Blavatsky’s “Himalayan Brothers.”[44]

~

In January 1882, William Quan Judge, the leading Theosophist in America, recently returned from Venezuela. The Society was in the process of growing, and Judge corresponded with Olcott on the movement’s progress. On January 16, 1882 Judge writes:

I have started a new thing here in Theosophy, I do not mean a new thing, but a new thing. Some people in Rochester ask for permission to organize a branch and I have said that they should make up a solicitation to the T. S. for a charter for Rochester. Parker Pillsbury is one of them. When that solicitation is signed, I agree to forward it to India for the issuance of the charter, which is to be sent to me or to Doubleday. Meanwhile they are to organize into a provisional association, so that when they get the charter a good-sized society can be organized. Of course the charter will be directed to the Society’s Officers in New York and not to the Rochester men. I think you had better send with it or immediately on receipt of this a dispensation to the Society here permitting organization by us of branches wherever we may see fit, and if you think it just as well perhaps you can send it now so that it may cover the Rochester case and avoid a special charter. Of course you will consult them on this because, now that I reflect upon it, it seems a little curious that Rochester where the rappings began should loom up as a possible place for a strong advance of Theosophy. It would be a thing to throw at the Spiritualists. Still I suppose N.Y. is really the beginning of the movement. The people who propose it in Rochester are members of the liberal league there, and whether they are good or not for the Society I do not know. What I have always been afraid of is that we might get in some people who would not do us any good, for here in the U. S. the people who first run after such an “ism” as ours are generally the crackbrained spiritualists and free-lovers, none of whom I care to have in.[45]

What Judge was referring to by “isms,” was a phenomenon which would be given the name “fad.” The word became popular in America in the 1880s to describe “[a] trivial fancy adopted and pursued for a time with irrational zeal; a matter of no importance, or an important matter imperfectly understood, taken up, and urged with more zeal than sense.”[46] January 1882, the time when Judge wrote the above letter, America would embrace its latest “fad,” the “Aesthetic Fad,” when “a tall, lank, Cassius-looking individual came from over the sea, and talked to [America] about violets, poppies, and sunflowers.”[47]

Oscar Wilde c. 1881 (wiki)

The “Cassius-looking individual” being Oscar Wilde, “the young poet whose connection with the aesthetic movement in England has made famous,” who arrived in New York on January 2, 1882.[48] He was in America to produce his first play, “Vera or, The Nihilists,” at New York’s Union Square Theatre, and embark on a nation-wide lecture tour.[49] Wilde praised the beauty of the sunflower while touring America, which lead to its adoption as an emblem of the aesthetic movement.[50] When he lectured in Boston, sixty Harvard men emulated Wilde’s sense of fashion, wearing “dress coats, knee breeches and large green neckties,” and it was said “large clusters of lilies were in their coats, and each carried a sunflower.”[51] In America, for a time, both prose and poetry were “full of rose-water.”[52] As the papers stated: “[Wilde had] been the subject of much ridicule in the English papers.[53] Just days after his visit to Boston, Wilde made a pilgrimage to New Jersey to meet Walt Whitman. They hit it off well (very well according to some.) Wilde seemed to Whitman “like a great big, splendid boy.” So “frank, and outspoken, and manly,” he didn’t see why such mocking things were written about him.[54] Whitman was in the process of issuing a new edition of Leaves of Grass, of which he was having difficulty publishing owing to censorship. It was a book which Wilde’s mother, “Speranza,” read to him as a child. Though it was not widely circulated, Lady Wilde managed to procure an early copy.[55] Following the “Aesthetic Fad,” there was the “Philosophy Fad.” L.J Vance writes:

The philosophic “fad” was more or less local. It finally centered around Concord. The first and second rate philosophers who had a “fad”—cult, I believe, is the proper word—vigorously worked it for all it was worth. Each one was anxious to found what he called a “school.”[56]

This is a reference to the Concord School of Philosophy, which was established by Bronson Alcott in 1879 and lasted until 1888. It, in many ways, foreshadowed the pedagogical innovations of the twentieth-century, anticipating, for example, Summer Schools and Extension Lectures. As Austin Warren stated, “Concord was already holy ground when the School of Philosophy was projected.”[57] Alcott, the Dean of the School, had been a friend of the famous men and women of the New England Transcendentalist Movement (some of whom were still alive.)

Louisa May Alcott (wiki)

Though well-known as a philosopher, his celebrity nowhere near matched that of his famous daughter, Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women (Vol. I: 1868, Vol. II: 1869.) The school really gained its footing when William Torrey Harris, a “gentle Hegelian,” arrived in Concord in 1879.[58] Harris, born in Connecticut in 1835, was an education reformer who lived for some time in St. Louis, Missouri. He was responsible establishing the first public kindergarten in the United States, as well as ensuring that high schools be included in public schooling. Harris also helped found the St. Louis Philosophical Society which was the main impetus for the philosophical movement known as the “St. Louis Movement.”[59] The first session of the Concord School opened its five-week course at Alcott’s Orchard House on July 15, 1879. Louisa May Alcott would write:

The town swarms with budding philosophers, and they roost on our steps like hens waiting for corn […] If they were philanthropists, I should enjoy it; but speculation seems a waste of time when there is so much real work to be done. Why discuss the “unknowable” till our poor are fed and the wicked saved.[60]

In the ensuing years, a wide array of speakers with discourses broadly defined as metaphysical would make an appearance at the Concord School, one such example being the Platonist, Alexander Wilder, one of the earliest names on the Theosophical Society register, who spoke there in 1882.[61] It was Wilder who encouraged Thomas Moore Johnson, a lawyer from Osceola, Missouri to begin publishing the journal, The Platonist, in 1881.[62] Johnson learned through Wilder about the Theosophists, and came to see the organization as promoting the same philosophical expression that he believed was practiced by the ancient Greeks.[63] Johnson and the Theosophists were sympathetic with one another’s projects, and advertised their respective magazines in each other’s literary organs. (In 1883 Johnson would join the Theosophical Society and team up with Elliott Bruce Page to establish the St. Louis T.S., otherwise known as the “Pioneer T.S.”)[64] It was the same summer of 1882, when we are introduced to another figure that would figure into Boston’s early Theosophical History.

GEORGE CHAINEY

George Chainey (1851-1935) was born in Kent, England, but immigrated to America in 1868. In the early 1870s Chainey married Martha Foster, with whom he had three children, Ralph, Earl, and Clair.[65] In 1876 he became a naturalized citizen of the United States, and working as Methodist preacher in Indiana.[66] By the end of that decade he would develop into a Unitarian minister, before ultimately moving the family to Boston where he was a Freethought lecturer.

George Chainey.[67]

In 1881 he published a journal called The Infidel Prophet (which was succeeded by another journal called The Word.) Like his colleague, Robert Ingersoll, Chainey was well on his way to being a leader of the secularists and of New England.[68] In 1882, Chainey enthusiastically defended the publication of Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” when it was threatened by censorship from The New England Society for the Suppression of Vice.[69] Chainey writes:

“Leaves of Grass” has long been to me a sacred and inspired book. I never received from it aught save inspiration to be true to the highest and best. When, under the instigation of that saintly scoundrel, Anthony Comstock, an attempt was made to suppress its publication, I felt my blood burn as though my mother had been insulted. I hastened at once to speak hot words of defiance against such injustice. I read in public and printed some of the condemned portions of the work. Postmaster Toby, of Boston, acting in concert with Comstock, tried to keep that issue of the paper out of the mails. I telegraphed the case to Col. Ingersoll, he called upon Postmaster General Howe, and before Mr. Toby was fairly awake, he was confronted with an order from headquarters politely in forming him that he was transcending his authority and commanding him to remove the embargo. The last time I saw Whitman I was glad to learn from his own lips that this action of mine had done more than anything else to help the sale of “Leaves of Grass.” I shall always be proud of that service.[70]

THE PERFECT WAY

Maitland and Kingsford’s “illuminations” had culminated in the work, The Perfect Way, published early in 1882. It was then that Marie urged Maitland and Kingsford consider the Theosophical Society, confessing her belief in Blavatsky’s “Himalayan Brothers.” Both Maitland and Kingsford joined the Theosophical Society on January 3, 1883.[71] Four days after joining, Kingsford was elected President of the London Theosophical Society, with Maitland as Vice-President.[72]

Marie joined the Theosophical Society a month later, on February 2, 1883. She immediately established the Société Théosophique d’Orient et d’Occident (France’s first Theosophical Society Branch.)[73] Meetings for the Société Théosophique were held on Thursdays and Sundays at the Parisian “Holyrood.” Emilie de Morsier, a niece of Ernest Naville (a renowned Swiss theologian) was named the Secretary of the Société Théosophique. Morsier, a tall woman in her early forties with permanently faded blonde hair, had very active at the Paris Congress of women in 1878. Like Blavatsky, she was a good musician and a “first-rate singer.” She dreamed of a career in music in her youth, but family prejudices, “hard as the stones of the Swiss mountains,” prevented her from realizing that potential, which was the great sorrow of her life. It was her dissatisfaction with the “dryness of the Protestant sectarianism” as well as “the various abuses of militant Catholicism,” that led her quench her spiritual thirst with Theosophy. She sent a letter to Blavatsky in India who immediately recognized her “passion and eloquence.” Blavatsky replied to Morsier with a letter containing “some dried rose petals” said to be the benediction of Mahatma Kuthumi.[74]

In the summer of 1883, Kingsford wrote a letter to Marie stating that she was changing the name of the London Theosophical Society to “the London Lodge of the Theosophical Society.” As is the case when new management makes changes too quickly, personalities began to clash within the Lodge. In this case, Kingsford felt compelled to direct the group toward the occident over the orient. [75] It was the belief of Kingsford and Maitland that the “revival of Christian mysticism [was] the form of Theosophy best adopted to the genius of European mind.”[76]

CEPHALONIA

In New York, W.Q. Judge was resurrecting Theosophy in its birthplace. He met the journalist, Laura Holloway in 1883, and her mutual enthusiasm for Eastern traditions and heterodox beliefs was something of an inspiration.[77] The Aryan T.S. (New York) was chartered in December 1883.[78] In January 1884, Judge’s article, “Psychometry,” was published in Johnson’s The Platonist.[79] A month later he would set sail for Europe and rendezvous with Blavatsky and Olcott, who were traveling with the Indian Theosophists, Mohini Chatterji, and Babula. Judge left New York on February 27, 1884, on board the S.S. Cephalonia. The prospect of the voyage looked ominous for passengers who were superstitious. The morning the vessel left dock she was involved in a collision with a tugboat which resulted in several deaths. Judge, who arrived in England on March 9, 1884, was not among the injured and deceased.[80]

He spent the intervening weeks exploring the environs of London while waiting for news from Blavatsky in Olcott.[81] Judge met Mary Gebhard, a former-pupil of the occultist Eliphas Levi. Born Frances Catherine Mary L’estrange, Frau Gebhard was, like Judge, a Dubliner by birth. When living in New York in 1852, Frances married a German consul named Gustav Gebhard, with whom she would have several children.[82] (One of her sons, Arthur Gebhard, lived at 27 West Fifty-first Street in Manhattan, and would, for some time, help Judge revitalize the movement in America.)[83]

RIVIERA

Blavatsky and Olcott arrived in France in March 1884. While Mohini and Babula continued on to Paris to meet with Judge, Blavatsky and Olcott stayed with Marie at her Winter villa in Nice, the Palais Tirauty.[84] Marie did everything within her power to make them feel at home, and to drew around Blavatsky the cream of the nobility that flock to the French Riviera in the colder months. There was an evening with the Camille Flammarion, famed astronomer of the Paris Observatory, and member of the Society since 1880.[85] On another occasion they convened with Agathe Sophie Henriette Haemmerle, the Russian wife of borgmester Johann Haemmerle. A lady of high culture and an impressive linguist, Agathe was a regular correspondent with a great many noted European savants in the different fields of the emerging discipline of “psychology.” (Jean-Martin Charcot, France’s pre-eminent neurologist, and director of Salpêtrière Asylum was conducting hypnotic experiments at this time.)[86] Olcott accompanied Agathe to a public lecture on mesmerism and psychology by the Italian mesmerist, Francesco Guidi.

On March 28, 1884, Blavatsky and Olcott rendezvoused with Judge and Mohini in Paris where they resided at an apartment which Marie secured for them at 46, Rue Notre Dame des Champs.[87] Blavatsky attended the following Sunday meeting of the Société Théosophique, where the rooms were “washed in the glow of a thousand candles.” (Had it been during the day they would have been illumined by the sun through the massive stained glass dome above their heads.) The members, mostly aristocrats, lawyers, professors, and doctors, mingled about the salons discussing the arrival of Blavatsky. One such member was the eminent bacteriologist, Professor Louis Olivier.[88] He was interested in “psychical research,” and compared the Theosophical Masters to what Charcot called “direct perception.”[89] According to Blavatsky, Marie had a falling out with Anna Kingsford, writing:

The Duchess is not such a friend of [Kingsford] and [Maitland] as you think. She has unbosomed herself to Olcott and me. She is their victim rather. She has paid for publishing their [Perfect Way] given them her ideas, and they never so much as thanked her or acknowledged it. They are ungrateful. Now she is our not their friend. But she seems in awe of the divine Anna.[90]

Olcott continued on to London to arbitrate a meeting of the London Lodge. It was decided, then, that Kingsford and Maitland would split from the Theosophical Society, and establish their own group, The Hermetic Society.[91] It was at this time that Olcott met Sir Edwin Arnold, and was invited to lunch with him. “He gave me the valuable present of some pages of the original manuscript of The Light of Asia,” Olcott writes. It was at the same time that Olcott met the poet, Robert Browning, and “talked some Theosophy with that master of verse.” [92] A literary cultus had developed around the poet in 1881, with the formation of the London’s Browning Society. During the April meeting of the Browning Society, James Russell Lowell, the American Minister, was the guest chairman.[93] It was an eventful evening. Evidently a young man named George Bernard Shaw actually stood up in the face of the whole solemn conclave of the Browning Society and expressed his conviction that Browning was “really one of the least dramatic poets that ever lived.” This caused a convulsive tremor to run through the audience, and the ladies and curates made a motion as if to tear the blasphemer limb from limb, but, observing that he was a tall and athletic Irishman, and “allowed mercy to season justice.”[94]

PARIS

Back in Paris, Judge expressed his concerns to Olcott, that Mohini was garnering unwanted attraction. In a letter to Olcott on May 11, he described the behavior of the French Theosophists. “[At the meeting] there were two broad-breasted women, décolleté, three who openly expressed admiration of his eyes.” Judge continued. “[Mohini] is obliged to wear his overcoat in the hot street or be the cause of an enormous crowd.”[95]

At the invitation of the Countess d’Adhémar, Blavatsky, Judge, Mohini, Bert Keightley, and Countess Wachtmeister, stayed as guests at Château Écossais à Enghien twenty miles north of Paris. At Blavatsky’s request, Judge made indices at the foot of each page of Isis Unveiled, as she planned to use it in preparation for The Secret Doctrine.[96] For several days, the party who accompanied Blavatsky witnessed displays of her occult powers, such as the ringing of the astral bells.[97] “The whole house was full of these bell sounds at night,” Judge said. “They were like signals going and coming to H.P.B.’s room downstairs.”[98] Three weeks later they returned to Paris, where they were soon joined by Vera Petrovna, and their aunt, Nadya Fadyeff, both of whom joined the Society before the end of the month.[99] At the same time, the newlyweds, Oscar, and Constance Wilde, who were in Paris for their honeymoon, paid a visit to Blavatsky (and the Theosophists,) just as they had done in London.[100] Shortly before his wedding, Oscar, and his brother William, attended a “muscle-reading” demonstration by Stuart Cumberland with Olcott.[101] The Wilde brothers, and their mother, Lady Wilde, also attended a Theosophical soirée where they were introduced to Mohini. “I never realized before what a mistake we make in being white!” said Wilde upon meeting Mohini.[102] Unimpressed with Wilde’s unsolicited “witticism” at his expense, Mohini would state: “[In English salons] you are presented to one who thinks he is amusing himself by making some stupid remark to you and indulging in talk of no profit to anyone.”[103]

Mohini could not escape the unwanted attention. This was most evident when attending the opera with Blavatsky and Vera. They had box seats for a performance of Léo Delibes’ opera, Lakme, a “délicieux conte Hindou,” at the Salle Favart (Opéra Comique.)[104] Based on Théodore Pavie’s Les babouches du Brahmane, the setting of Lakmé was contemporary British India, and told the tale of the Brahmin, Nilakantha, who rebelled against the British, and his daughter, the titular Lakmé, who fell in love with a British officer.[105] The audience, however, was more captivated by Mohini than the parody on the stage. They stared at him for the duration of the performance.[106] While in London, Mohini met Clara Erskine Clement Waters and her husband, Forbes Winslow Waters, owner of the Boston Daily Advertiser. The couple had joined the Society in August 1884.[107] They invited him to America with them.[108] At the end of the summer, Judge continued his journey to Adyar, India. Laura C. Holloway, meanwhile, arrived in London. Together with Mohini, she would co-author the book, Man: Fragments of Forgotten History in 1885.[109]

KIMBALL AND CHAINEY

Back in Boston, George Chainey, the man who defended Whitman, had a change of heart regarding Spiritualism. In the summer of 1884, after attending a séance with Anna Kimball (with whom he began an extramarital affair,) Chainey spoke glowingly of the movement. Writing of this encounter, Chainey states:

I […] met Mrs. Anna Kimball, a celebrated psychometrist. As Prof. Denton, who made a special study of this subject, gives her the palm in this field, I gave her a ring I had been wearing to hold. She soon made me feel like the woman of Samaria, who said of Jesus: “Come see a man who told me all that ever I did.” As a seer or clairvoyant she described the spirits of two young ladies, standing by my side, who gave their names, and said I visited them when they were sick, and preached their funeral sermons—all of which was true. She also described another spirit standing by, who was my guardian angel […] I began to be somewhat shaken, and to catch myself saying: “Great heavens! is it all true?” But, then, I thought of all the trickery and fraud that has been exposed in Spiritualism, and all that I must undergo should I proclaim myself a Spiritualist, and said quietly to myself: “No it won’t do. I have changed around enough.” It seems to be true, but I will just keep this to myself, and say nothing about it. Being under engagement, I attended another séance. This time the manifestations were still more wonderful. The room seemed crowded with spirits, audible voices speaking all around us giving names and messages fully recognized by some of the sitters.[110]

Over the summer of 1884 Kimball and Chainey began to gravitate towards Theosophy and the Theosophical Society. Marie likely had in a hand in guiding Kimball in this direction. Whatever the case may be, she was certainly aware of Kimball’s interest in Theosophy, for in a letter to Kimball she writes: “I am so glad to hear that you are happy in your theosophical pursuits and studies, and that you have so intelligent and congenial a co-laborer, as I am sure Mr. Chainey must be, from all you tell me, and from all I read from his pen.”[111]

~

On October 6, 1884, after conducting his investigation in Adyar, and before returning to New York, Judge attended the inaugural meeting of the Samuskrita Basha Abhi Virtini, the new Sanskrit school at Madras Christian College.[112] The paper read that evening, “The importance of Sanskrit literature,” expressed the sentiment and that, “a study of Sanskrit would raise India among the civilized nations of the world.”[113] Weeks later, in December 1884, Raghunathrao would host a meeting in his home that would be the genesis of the Indian National Congress of 1885.[114] For their part, the Bombay Branch T.S. were “collecting funds to enable [them] to send out Theosophist Missionaries to preach peace and good-will, not only all over India, but also in Europe and America.”[115] The two men sent to America, Govindarao Sattay, and Gopalrao Joshi, would arrive in America around the same time as Judge, who returned home to New York on the S.S. Wisconsin, arriving on November 26, 1884.[116]

Chainey and Kimball, meanwhile, both joined the Rochester T.S. in October 1884.[117] (Theosophists in New England looked to the Rochester T.S. at this time, as they yet had a Branch of their own.) By November 1884 Kimball and Chainey would establish a group called The Society of the Perfect Way (the name being a reference to the 1882 eponymous book by Kingsford and Maitland.)[118] In January 1885 Chainey and Kimball changed the name of their group to The Boston Hermetic Lodge of Theosophy, and hold regular meetings in the parlor of their residence, 310 Shawmut Avenue.[119] While this change of name could be a nod to the London-based Hermetic Society, there was another factor at play. In January 1885, another group (not affiliated with any Theosophical body,) was established in Boston, known as The Hermetic Club. It was among the first of the “literary fads” that connected with the “philosophy fad.”[120] William Torrey Harris, the “gentle Hegelian,” from the Concord School, was invited to be the leader by a Committee comprised of Caroline Guild (née Whitmarsh,) Emily Baldwin Hale (née Perkins,) Alice Ayres, Mary Dewey, Josephine Davis (née Ellery,) and Mary Cobb (née Wells.)[121] This Society met part of the time with Josephine Davis at 120 Highland Street (Roxbury, Massachusetts,) and part of the time in the home of Samuel E. Sewall, 4 Park Street (Boston, Massachusetts.)[122] The timing of the name change may have been a simple coincidence, but Kimball and Chainey would have known that any confusion among outsiders regarding the names The Hermetic Club and The Hermetic Lodge of Theosophy, would only stand to benefit them. The Boston Hermetic Lodge of Theosophy was ultimately rejected by administrators of The Theosophical Society. It is unclear what prompted this pivot towards Theosophy, but Marie may have played a role in this, as she was certainly aware of the enterprise. “I am so glad to hear that you are happy in your theosophical pursuits and studies,” Marie writes to Kimball, “and that you have so intelligent and congenial a co-laborer, as I am sure Mr. Chainey must be, from all you tell me, and from all I read from his pen.”[123]

In the spring of 1885, Kimball and Chainey made their way out west to California. Along the way, they stopped in Salt Lake City April 17, 1885, where Kimball met with her Mormon family and friends.[124] Soon after they arrived in San Francisco, they met the Theosophist, Gopalrao Vinayak Joshi, who arrived from India in June 1885. Gopalrao was soon attending séances conducted by Kimball.[125]

We had the pleasure of meeting him shortly after he landed in San Francisco, and derived much benefit from his instructive con versation and descriptions of life in India. Through introductions we could furnish him and other friends in San Francisco, he made his way to Philadelphia by lecturing on the route.[126]

Gopalrao, likewise, was very impressed with the duo.[127] In June 1885 Gopalrao left California for Utah, where he would lecture en route to Philadelphia, where his wife, Anandibai, was attending medical school. Kimball supplied Gopalrao with a letter of introduction to her cousin, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, to help facilitate his travels.[128]

The Gnostic

In July 1885 Kimball and Chainey would publish the first issue of their proto-New Age journal, The Gnostic.[129] They also established “The Gnostic School of Psychic Culture and Physical Culture.”[130] This would overlap with their other project, the first Theosophical “branch” in California. (It began on October 12, 1885, with meetings held at 112 McAllister Street in San Francisco.)[131] The “branch” was both short-lived and unsanctioned by the American Board of Control (of Theosophy.) It is likely that Kimball and Chainey also had a hand in introducing Gopalrao to Whitman, who was a reader of The Gnostic.[132] By November 1885, Gopalrao had joined Anandibai, in Philadelphia. The same month Whitman would pay the Joshis a visit.[133] (In 1886 Chainey was granted a divorce from his wife.[134] He would subsequently marry Kimball and relocate to Australia for some time.)[135]

THE “BROWNING FAD”

The “Browning Fad,” also known as “Esoteric Browningism” arrived in Boston in December 1885.[136] This sentimental literary cultus, as the name suggests, focused its attention on the poetry of Robert Browning. It was established as an off-shoot of the short-lived “Boston Hermetic Society,” by the literary circle of that group.[137] (By 1886 other Browning Societies formed around the nation, endeavoring to study the mysterious and hidden meaning behind the words of that ambiguous poet.)[138] “One would have thought that Browning wrote his poems in the same way that Ignatius Donnelly says Shakespeare wrote his dramas—in cipher,” it was said. Days after the creation of the Browning Society (perhaps even in response to the Browning Society) Arthur Gebhard, and two Bostonians who belonged to the Rochester T.S. (Charles R. Kendall, and Hollis B. Page) helped establish the first Lodge in Massachusetts, the Malden T.S..[139] (see The Nationalist Club)

In the mid-1880s Theosophy (then synonymous with Buddhism,) had proven to be very popular with educated women in New England in New York and had replaced sentimental literary cultus of the poet Robert Browning known as “Esoteric Browningism.”[140] Theosophy was “rapidly becoming a prominent Boston ‘fad,’” and followed “closely on the heels of Browningism, with a possible case of pushing it to the wall and keeping it there.” The new “ism,” it was said, had “not taken any very firm hold, as yet, upon the masculinity of the Hub, but the gentler sex has become largely infected by it, and there is every prospect that it will soon be an all-pervading epidemic with them.”[141] “The ‘intellectual circles’ of Boston,” however, found “much food for thought and discussion in the literature produced by wholesale under the direction of Blavatsky,” at the time, and “the current of truth flowing through the society’s channels makes itself felt” in the inquisitive Puritan capital.”[142]

Celia Thaxter. (Source: Wiki)

The writer, Celia Thaxter, developed an interest in Theosophy.[143] She began a communication on the subject with Gebhard, and it is likely that her interest generated significant interest among the New England literati.[144] Celia and her friend, and fellow writer, Ida Botha, would both join the Society on January 1, 1886.)[145] Thaxter would write to a friend on February 9, 1886:

Thanks for your note. I am so fortunate as to have found a copy of “Five Years of Theosophy,” & wonderful & delightful it is. I was in luck, for I think it is the only copy in Boston for sale. Cupples & Upham are going to have Light on the Path with the notes in a few days, so don’t you take any trouble for me, my dear. I fully appreciate & thank you for your goodness, but I know what it is to be as busy as you are, & you mustn’t take the time when I can reach the notes without your doing so. I shall write to Mr. Gebhard. I am sure we shall none of us be sorry, my dear friend. Ida Bothe is so happy about it! I wish you knew her. She is a fine creature, deeply thoughtful, eager for the truth. I am sure you would like her. I hope to see you soon.[146]

In March Gebhard returned to Boston and delivered a small talk on “The Ideals of Richard Wagner, as they bear on Theosophy.” Several Bostonians were in attendance, and a “general discussion on ancient myths in the light of Theosophical ideas was held.”[147] In letter from W.Q. Judge to Olcott at this time, he writes: “Well, from his return here until I got things in shape here with Gebhard and everything booming in Boston.”[148] Celia, for a time, would be described as “more profoundly versed in Theosophy than anyone in America.”[149] Ida Botha, invited Gebhard back to Massachusetts to speak in the parlors of Sara Bull. Their support interest helped generate significant interest among the New England literati.[150]

Sara Bull (wiki)

Conference Room in Sarah Bull’s Studio.[151]

Julia Campbell Ver Planck, who would become a close friend of Judge, would join at this time. A contributor to Harper’s Magazine, Julia was a playwright of some renown who won praise in 1884 for her dramatic retelling of the Salem Witch trials in The Puritan Maid. This was followed by a drama called Sealed Instructions which had a very successful run at Madison Square Theatre in the spring of 1885. Her father, James Hepburn Campbell, was the former American Minister to Sweden, and her mother, Juliet Hamersley Lewis was a poet of repute. Though Julia had a successful literary career, her life was marked with tragedy. A decade earlier her entire family died; first her two boys, James, and Gordon in 1875, and then her husband, Phillip, in 1876.[152] Her boys were still infants when they passed away, and Judge understood well the sadness which lingered from such a loss.[153]

It was during a chance conversation about Blavatsky with Ida Botha over lunch, that Julia became interested in Theosophy. Botha, “whose circle comprised almost every distinguished member of society at home and abroad,” invited Julia to accompany her to hear Arthur Gebhard speak on Theosophy with her and Celia Thaxter in the parlor of Sara Bull.[154] The impression made upon Julia was so deep that she joined the T.S. within two weeks.[155] In a letter to Clara Waters at this time, Judge writes:

I see already springing up through the misdirected notions of theosophists who are leaning and longing after psychic culture. For I know that a good many persons are so hankering after what they call “knowledge and light” but which in reality is a desire to find occult power, that they are willing to hunt all through the Theosophical Society for it but are not willing to put the society publicly on its true philosophical and moral basis, nor do they say ought to their children. Many of them say “we will not belong to an organization,” but we want to study occultism, and some theosophists are not willing to lose what seems possible material for the Cause. But the children of today are the adults of a few years hence, and if in some way they can be put on the right track, so much the better for the race of which they will themselves in turn be the guides. Your words on this subject to the Boston Theosophists and to the liberal minded among your friends, have great weight and might cause large and wide spreading trees of deed and thought to grow up. The next question is regarding many people in Boston who have not joined the Society for various reasons. Is there any possibility of their joining the N.Y. Branch while they are waiting the Coues developments? They could do this and remain unknown if such was their wish, and at any time withdraw for the purpose of forming a body of their own in Boston. I thought perhaps if I could solidify all theosophists and inquirers by these notes of ours — now small but easily enlarged—much good would be done. I shall write all the Branches to try and get a fund started for a general monthly Abridgment: all questions and replies and discussion notes to go to one place, say here and then to be printed after proper editing and distributed to all. I printed 300 last month and they are all gone now, such is the demand. I suppose the task of editing say 8 pages per month would be putting too much on your shoulders. But Baxter could do it—We here are not striving to claim the honors, we only wish the work done. It seems well to do it here; but I must confess it is rapidly assuming larger proportions than I dreamed of — and am satisfied that very soon so many questions (replies are nil) will come along that 4 pages will not do.[156]

At the end of 1886 a Branch was formed in Boston proper with six members. In the spring of 1887, Charles R. Kendall of Rochester was named President.[157] Meetings were held in the home of Helen M. Coy at 80 West Newton Street, where essays were read and discussed.[158] They had little to say about Blavatsky, for they “discouraged the childish desire for mere phenomena,” and spent their time discussing ethical problems, “seeking each in his own soul alone the solution of the Sphinx’s riddle.”[159]

SCANDAL

Back in London, Mohini was involved in controversy. One newspaper wrote: “If this should meet the eye of Mohini M. Chatterji, lately of India, he is implored to return to his wife and child.”[160] It was said that he left London in the midst of a romantic scandal that was checked in the press by William Wilde, “a man occupying an important journalistic position,” and the brother of Oscar Wilde.[161] Blavatsky agreed to “let Mohini visit America & work there, as he appears to have decided to do so.”[162] Mohini’s relationship with the Theosophical Society was strained.[163] Privately Blavatsky would say of the scandal:

The Anglo-French messaline who, inveigling Mohini into the Barbyan wood, suddenly, and seeing that her overtures in words were left without effect—slipped down her loose garment to the waist leaving her entirely nude before the boy—is not the worse one in the Oriental group. Of all those pure “Vestals” she is only the most frankly dissolute, but not either the most lustful or sinful. She had no sacred duty entrusted to her to fulfill. She must be a cocotte by nature and temperament—she is neither hypocritical, nor does she aim at public saintliness. There are others in the group, and not one but four in number who burn with a scandalous ferocious passion for Mohini—with that craving of old gourmands for unnatural food, for rotten Limburg cheese with worms in it to tickle their satiated palates, or of the “Pall Mall” iniquitous old men for forbidden fruit—ten year old virgins.[164] Oh, the filthy beasts!! the sacrilegious, hypocritical harlots! […] I have all the proofs in hand: letters, notes, and even confessions, AUTOGRAPH CONFESSIONS to little D.N.—imploring him—what do you think —to forgive them? Oh no; but to help them to satisfy their unholy lust, to influence Mohini to yield to them “once—only once!” Let us all bow before the purity of the poor Hindu boy. I tell you no European would have withstood the pressure. So foolish he was, so little vain […] [Mohini] had never understood what those females were driving at.[165]

Mohini left England on November 13, 1886, on the Aurania. At the same time, Mohini was coming to stay with Arthur Gebhardt, who offered to host Mohini for the winter in his home at 27 West Fifty-first street. Mohini, wishing to take advantage of any opportunity to further his work, gladly accepted.[166] Arriving in New York harbor a week later, he was among the first to witness the illuminated Statue of Liberty, which “reminded him somewhat of the Hindu idols in his own country.”[167]

Mohini Chatterji (Harvard Library)

At the docks he told reporters: “I am a member of the Theosophical Society, but I do not call myself a Theosophist, because that seems to imply the possession of absolute knowledge of the truth, whereas I am merely a seeker.”[168] His disaffection with Blavatsky caused him to decline all public invitations by the Theosophists except for a few he promised to make for Judge.[169] In keeping his word to Judge, Mohini spoke before the New York Branch soon after his arrival.[170] Despite his drift from the movement, one of the first people he called upon was Laura C. Holloway.[171] While in New York, Mohini would discuss the difference between Western philosophy and Eastern philosophy, he states:

[Emerson’s] school has borrowed freely from the lore of the East, and the fructifying force in their concept they owed to India. Coming down to the present time I find a powerful current in thought in Germany, and I recognize many familiar ideas in it. On inquiry I learn that this is the philosophy of Schopenhauer; but when I read Schopenhauer, I see behind him the wisdom of the Vedas. He indeed has twisted and distorted the truth thus derived, for he has attempted the impossible feat of serving God and Mammon at the same time. A working union of Materialism and Spiritualism is out of the question. Schopenhauer has only succeeded by forcing these incompatible elements together, in producing that negation of all sound thought which you call Pessimism.[172]

On March 29, 1887, Mohini delivered a lecture, “Indian Theosophy: Its Relation to Western Civilization,” before The Nineteenth Century Club.[173] Membership in the Society was slowly increasing, and the space in the Union Square Hall proved to be too small. In the early months of 1887, The New York Branch secured a room from the Constitution Club in Mott Memorial Hall, but as Mohini’s talk was expected to garner a larger audience, a room in the American Art Gallery at Madison Square South was rented.[174] The following day, March 30, 1887, Holloway hosted Mohini at her residence at 181 Schermerhorn Street, where he gave a more intimate talk on spirituality in general.[175] During these talks, Mohini discussed “how Indian ideas were influencing Europe,” and attracted general attention with his eulogies of primitive Christianity. Mohini made the claim that all spiritual ideas had their origin in the East. “Materialism and ecclesiastical corruption,” he stated, “encrusted the living faith,” of Christianity, and its beauty could only be restored from the East.[176] “Christianity is at one with the Vedantic sacred canons in teaching that ‘the Kingdom of Heaven is within you,’” Mohini stated.[177] The field for this “Theosophical Christianity” was first surveyed by his brother in the Brahmo Samaj, Pratap Chunder Mazumdar, whose Oriental Christ was gaining traction in America.[178]

Mohini then went to Boston, where he produced a translation of the Bhagavad Gita under the patronage of Clara and Clement Erskine Waters (who was rumored to have built a chapel for Mohini’s use near her home on Newbury Street.)[179] Mohini left America in late 1887 to return to India, stating he would never return to the West again.[180] His impact on the city, however, was tangible. The religious atmosphere of Boston was changing. “The Unitarianism of New England seems to be declining,” said one paper. “Not so much, perhaps, in favor of orthodoxy as because it is assuming new forms and merging more into what they are pleased to call the ‘Free Religious’ societies.”[181] (It was at this time that Hiram Butler was operating the Society Esoteric.) It was said that Sigmund Bowman Alexander’s 1888 novel, The Veiled Beyond, was inspired by Mohini’s teachings.[182] Celia Thaxter would state:

I am become a most humble and devoted follower of Christ, our Christ, for all races have their own Christs to save and help them , one being especially sent for us, “to call sinners to repentance and not the righteous.” I understand it all now and feel as if all my life I had been looking through a window black with smoke; suddenly it is cleared , and I see a dazzling prospect, a glorious hope! There are two elements which Mohini brings which make clear the scheme of things: one is the law of incarnation, the rebirth is upon this earth, in which all the Eastern nations believe as a matter of course ,and to which our Christ refers in one or two of the gospels; and the other, the law of cause and effect, called Karma, the results of lives in the past. When salvation is spoken of, it always means the being saved from further earthly lives, and of reaching God and the supreme of joy, the continual wheel of rebirth and pain and death being the hell, the fire of passions that burns forever, the worm of desires that never die.[183]

~

In February 1888, Anna Kingsford died from pneumonia. It was around the same time that Chainey and Kimball separated, whereupon, in March 1889, Chainey moved to England where he resided at 17 Charleville Road.[184] (He would collaborate with Maitland on the journal, Psyche: A Journal of Mystical Interpretation.)[185] He was evidently in contact with Blavatsky. In letter from October 1889, Blavatsky writes to W.Q. Judge:

Now I ask you one thing. Can’t you take back poor George Chainey who is here, and readmit him into the T. S? It is this infernal E who pitched him out. Please do if you can. He is a magnificent orator & I want him here in the “Blavatsky Lodge” but unless you take him back, I cannot make him a member of the British Section or the Blavatsky Lodge, or can I?[186]

It was said that Chainey “was for a number of years in retirement, during which time he was in a state of mental illumination and clairvoyance, when he perceived a new meaning to the teachings of the Bible.” During this retirement he wrote a thirty-volume interpretation of the Bible, “from Genesis to Revelation.” By 1900 he was operating a “school of interpretation” in room 1021 of Chicago’s Masonic Temple.”[187] It would seem that Chainey and Anna Kimball (Chainey) divorced in 1903. Kimball died in 1920.[188] Chainey died in Long Beach, California, in 1935.[189] In his 1888 essay, “The New Religion,” Chainey anticipates a paradigmatic shift in the way that people interface with spirituality:

In speaking of a new religion I speak of things as they seem rather than as they are. The very idea of religion is foreign to the idea of what is either new or old. Both old and new belong to time. Religion belongs to eternity. Many attempts have been made to define religion. It is, however, something like trying to define why flowers are beautiful; or, to reduce to a cold and formal definition, the unspeakable emotion of love.[190]

~

In 1888 Marie established the occult journal, L’Aurore, which was devoted entirely to Theosophy and Spiritualism.[191] She would die on November 2, 1895, of heart disease.[192]

~

As for the cultural and academic impact all of this had on Boston and its surroundings, I will explore that in another piece about William James and Theosophy in Cambridge.

SOURCES

[1] Wolf, Annie. “An Eccentric Peeress.” The Philadelphia Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 29, 1889; “The Vice-Regent of Mary Queen of Scots.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 1. (January 1896): 81-83.

[2] Olcott, Henry Steel. “Death Of Lady Caithness.” The Theosophist. Vol. XVII, No. 3 (December, 1895): 183-185.

[3] Wolf, Annie. “An Eccentric Peeress.” The Philadelphia Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 29, 1889; “The Vice-Regent of Mary Queen of Scots.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 1. (January 1896): 81-83.

[4] Wolf, Annie. “An Eccentric Peeress.” The Philadelphia Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 29, 1889; “The Vice-Regent of Mary Queen of Scots.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 1. (January 1896): 81-83.

[5] The Countess of Caithness. “Remarkable Séances: No. III.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XIX, No. 7 (August 12, 1881): 79.

[6] Wolf, Annie. “An Eccentric Peeress.” The Philadelphia Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) December 29, 1889; “The Vice-Regent of Mary Queen of Scots.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 1. (January 1896): 81-83.

[7] The Countess of Caithness. “Remarkable Séances: No. II.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XIX, No. 5 (July 29, 1881): 54-55.

[8] Olcott, Henry Steel. “Death Of Lady Caithness.” The Theosophist. Vol. XVII, No. 3 (December, 1895): 183-185; “The Vice-Regent of Mary Queen of Scots.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 1. (January 1896): 81-83.

[9] “Interesting Experience Of Lady Caithness.” Light. Vol. XI, No. 556. (August 29, 1891): 419.

[10] “The Vice-Regent of Mary Queen of Scots.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 1. (January 1896): 81-83.

[11] Marie Sinclair. “A Midnight Visit To Holyrood.” The Gnostic. Vol. I, No. 5 (November 1887): 106-108.

[12] “A Titled Spiritualist.” The Illustrated American. Vol. XIX, No. 310. (February 1, 1896): 155.

[13] Godwin, Joscelyn. “Lady Caithness And Her Connection With Theosophy.” Theosophical History. Vol. VIII, No. 4 (October 2000): 127-147.

[14] The Countess Of Caithness writes: “It was a bright sunshiny morning in winter, and the snow was lying thick on the ground when we drove over to Harvard University, Cambridge, a few miles out of Boston, to pay a visit to the world-renowned Professor Louis Agassiz, who received us with all the courteous amiability, and all the finished suavity of manner of a man of the world, and of a refined and intelligent member of society.” [The Countess of Caithness. Old Truths In A New Light, Or, An Earnest Endeavour to Reconcile Material Science with Spiritual Science, And With Scripture. Chapman And Hall. London, England. (1876): 286.] As Agassiz died on December 14, 1873, we can surmise that this meeting did not occur in the later part of 1873. The Caithness’s attended a trial of the Westinghouse air brakes in Boston on April 1, 1873. [“Trial Of The Westinghouse Brake.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) April 2, 1873.] The Boston Evening Transcript states that Charles H. Minot hosted the Caithness’s at his home on Berkeley Street of April 3, 1873. [“Personal.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) April 5, 1873.] Though Caithness’s description of snow “lying thick on the ground” seems strange for April, records indicate that Boston experienced heavy snow that year, with 33 snow storms and 6-feet of snow. The last of the snow storms that season occurred on April 12 and April 13, 1873. [“Snow Storms The Past Season In Boston.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) April 17, 1873.]

[15] Henry Steel Olcott writes: “As early as 1857 the Faculty of Harvard University pronounced the opinion that ‘any connection with spiritualistic circles, so called, corrupts the morals, and degrades the intellect;’ and they even had the effrontery to say that they deemed it ‘their solemn duty to warn the community against this contaminating influence, which surely tends to lessen the truth of man, and the purity of woman.’” [Olcott, Henry S. People From The Other World. American Publishing Company. Hartford, Connecticut. (1875): v.]

[16] Putnam writes: “Did Agassiz either undergo any experiences, or put anything on record, which m ay lend aid toward opening a pathway to knowledge, that other actors and other forces than any which science has heretofore cognized and dealt with, actually exist just beyond where she has explored, and from thence are putting forth effective action upon mortals and human affairs? Possibly he did.” [Putnam, Allen. Agassiz And Spiritualism: Involving The Investigation Of Harvard College Professors In 1857. Colby & Rich, Publishers. Boston, Massachusetts. (1874): 4.]

[17] The Countess of Caithness. Old Truths In A New Light, Or, An Earnest Endeavour to Reconcile Material Science with Spiritual Science, And With Scripture. Chapman And Hall. London, England. (1876): 289.

[18] Lovell, John W. “Reminiscences Of Early Days Of Theosophical Society.” The Canadian Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 3 (May 15, 1929): 69-72.

[19] Barrett, Harrison D. Life Work Of Mrs. Cora L.V. Richmond. National Spiritualists Association Of The U.S.A. Chicago, Illinois. (1895): 690-693.

[20] “Fad Of A Rich Countess.” The Fort Worth Daily Gazette. (Fort Worth, Texas) November 11, 1894.

[21] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 10. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Emma Hardinge Britten. (11/17/1875.)

[22] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume I. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1895): 199.

[23] Kimball, Anna C. “A Message From Mrs. Kimball.” The Medium And Daybreak. Vol. VII, No. 311 (June 30, 1876): 407.

[24] “Photograph: Anna Kimball.” The Gnostic. Vol. I, No. 5 (November 1887): 87.

[25] Ancestry.com. Global, Find a Grave® Index for Burials at Sea and other Select Burial Locations, 1300s-Current [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

[26] “The Woodhull Convention.” The New Northwest. (Portland, Oregon) June 7, 1872; Mrs. Anna Kimball, The Mind Reader.” The Salt Lake Herald. (Salt Lake City, Utah) April 18, 1885.

[27] Kimball, Anna. “Leaves From My Life Book.” The Gnostic. Vol. I, No. 1 (July 1885): 18.

[28] Kimball, Anna. “Leaves From My Life Book.” The Gnostic. Vol. I, No. 2 (August 1885): 23-25.

[29] Denton, William. “Sideros And Its People As Independently Described By Many Psychometers.” The Religio-Philosophical Journal. Vol. XXIX, No. 12 (November 20, 1880): 2.

[30] Denton, William. “Sideros And Its People As Independently Described By Many Psychometers.” The Religio-Philosophical Journal. Vol. XLXX, No. 12 (May 14, 1887): 2.

[31] “The Formation Of The Star Circle.” The Medium And Daybreak. Vol. VII, No. 311 (March 17, 1876): 169-170.

[32] Kimball, Anna C. “A Message From Mrs. Kimball.” The Medium And Daybreak. Vol. VII, No. 311 (June 30, 1876): 407.

[33] Marie Sinclair. “A Midnight Visit To Holyrood.” The Gnostic. Vol. I, No. 5 (November 1887): 106-108.

[34] Olcott, Henry Steel. “Death Of Lady Caithness.” The Theosophist. Vol. XVII, No. 3 (December, 1895): 183-185.

[35] Godwin, Joscelyn. “Lady Caithness And Her Connection With Theosophy.” Theosophical History. Vol. VIII, No. 4 (October 2000): 127-147.

[36] Olcott, Henry Steel. “Death Of Lady Caithness.” The Theosophist. Vol. XVII, No. 3 (December, 1895): 183-185.

[37] “Lady Caithness’ Faith.” Lucifer. Vol. VIII, No. 43. (March 15, 1891): 84-85.

[38] Maitland, Edward. Anna Kingsford: Her Life, Letters, Diary, And Work: Vol. I. George Redway. London, England. (1896): 319-321.

[39] “The Countess Of Caithness.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XIX, No. 7 (August 12, 1881): 79-80.

[40] “A Titled Spiritualist.” The Illustrated American. Vol. XIX, No. 310. (February 1, 1896): 155.

[41] “The Countess Of Caithness.” The Spiritualist. Vol. XIX, No. 7 (August 12, 1881): 79-80.

[42] “A Titled Spiritualist.” The Illustrated American. Vol. XIX, No. 310. (February 1, 1896): 155.

[43] “Interesting Experience Of Lady Caithness.” Light. Vol. XI, No. 556. (August 29, 1891): 419.

[44] Godwin, Joscelyn. “Lady Caithness And Her Connection With Theosophy.” Theosophical History. Vol. VIII, No. 4 (October 2000): 127-147.

[45] “Letters of W. Q. Judge.” The Theosophist. Vol. LII, No. 8 (May 1931): 191-197.

[46] Smith, Benjamin Eli; Whitney, William Dwight. The Century Dictionary: Vol. III. The Century Co. New York, New York. (1895): 2115.

[47] Vance, L.J. “Literary ‘Fads.’ The Epoch. Vol. IV, No. 83 (September 7, 1888) 80.

[48] “Ten Minutes With A Poet.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 3, 1882.

[49] Kohl, Norbert. Oscar Wilde: The Works Of A Conformist Rebel. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (2011): 35.

[50] Nelson, E. Charles. “Helianthus Annuus ‘Oscar Wilde’: Some Notes on Oscar and the Cult[ivation] of Sunflowers.” The Wildean. No. 43. (July 2013): 2-25.

[51] “Current Events.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) February 1, 1882.

[52] Vance, L.J. “Literary ‘Fads.’ The Epoch. Vol. IV, No. 83 (September 7, 1888) 80.

[53] “Ten Minutes With A Poet.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 3, 1882.

[54] “Walt And Sweet Oscar.” The Nashville Banner. (Nashville, Tennessee) January 26, 1882.

[55] Mendelssohn, Michèle. Making Oscar Wilde. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2018): 127.

[56] Vance, L.J. “Fads.” Current Literature. Vol. II, No. 1. (January 1889): 29-30.

[57] Warren, Austin. “The Concord School of Philosophy.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. II, No. 2 (April 1929): 199–233.

[58] Boston Browning Society. The Boston Browning Society Centenary Yearbook. Boston Browning Society. Boston Massachusetts. (1912):17-18.

[59] Zimmerman, Kenneth. “William Torrey Harris: Forgotten Man in American Education.” Journal of Thought. Vol. XX, No. 2 (Summer 1985): 76–89.

[60] Warren, Austin. “The Concord School of Philosophy.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. II, No. 2 (April 1929): 199–233.

[61] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 20. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Alexander Wilder. (12/1/1875)

[62] Bregman, Jay. “The Neoplatonic Revival in North America.” Hermathena. No. 149. Special Issue: The Heritage of Platonism. (Winter 1990): 99–119.

[63] Bowen, Patrick D. “The Real Pure Yog.” Imagining The East: The Early Theosophical Society. (eds.) Rudbog, Tim; Sand, Erik Reenberg. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2020): 158-180.

[64] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2117. (website file: 1A:1875-1885); Elliot Bruce Page. [8/1/1883]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1882. (website file: 1A:1875-1885); Thomas M. Johnson. [4/17/1883]; “The Theosophists.” The St. Louis Post Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) November 10, 1884; “Theosophy.” The St. Louis Post Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) August 7, 1886; “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol II., No. 7. (October 1887): 222-224; Bowen, Patrick D. A History of Conversion to Islam in the United States: Vol. I. Btill. Leiden, Netherlands. (2015): 79-80.

[65] Year: 1880; Census Place: Evansville, Vanderburgh, Indiana; Roll: 317; Page: 320C; Enumeration District: 079. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C. [Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1880 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com.]

[66] Ancestry.com. Global, Find a Grave® Index for Burials at Sea and other Select Burial Locations, 1300s-Current [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

[67] Chainey, George. Paradise: Or, The Garden of the Lord God. The Christopher Publishing House. Boston, Massachusetts. (1925): Frontispiece.

[68] Schmidt, Leigh Eric. Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2018): 56-58.

[69] Kemeny, P.C. “‘Banned in Boston’: Moral Reform Politics and the New England Society for the Suppression of Vice.” Church History. Vol. LXXVIII, No. 4 (December 2009): 814-846.

[70] Chainey, George. “Walt Whitman.” The Gnostic. Vol. I, No. 1 (July 1885): 1-8.

[71] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1583. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Dr. Anna Kingsford. [1/3/1883]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1584. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Edward Maitland. [1/3/1883.]

[72] Godwin, Joscelyn. “Lady Caithness And Her Connection With Theosophy.” Theosophical History. Vol. VIII, No. 4 (October 2000): 127-147.

[73] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1638. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Marie, the Countess of Caithness and Duchess of Pomar. [2/2/1883.] Godwin, Joscelyn. The Beginnings of Theosophy in France. Theosophical History Centre. London, England. (1989): 9.

[74] Solovyov, Vsevolod Sergeyevich. A Modern Priestess Of Isis. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1895): 30-32.

[75] Godwin, Joscelyn. “Lady Caithness And Her Connection With Theosophy.” Theosophical History. Vol. VIII, No. 4 (October 2000): 127-147.

[76] (One Of Its Fellows.) The Newest Thing In Religions. The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) July 15, 1884.

[77] Carter, Laura Holloway. “William Quan Judge, A Reminiscence.” The Word. Vol. XXII, No. 2 (November 1915): 75-89.

[78] “Theosophy: A Secret Meeting Of Adherents.” The Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois.) December 5, 1883.

[79] Judge, William Quan. “Psychometry.” The Platonist. Vol. II, No. 1. (January, 1884): 5-6.

[80] “A Fatal Steamboat Collision.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) February 27, 1884; “Matters About The City.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 28, 1884; “The Mails.” Shipping And Mercantile Gazette. (London, England.) March 10, 1884; “Maritime.” The American Register. (London, England.) March 15, 1884.

[81] “The Theosophists.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California.) December 12, 1886; “Extracts From Letters Written By William Q. Judge From London In The Spring 1884.” The Word. Vol. XIV (October 1911-March 1912): 324-332.

[82] Frances Catherine Mary L’estrange (1832–1892) Catholic Parish Registers, The National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 08830 / 02; New York City, Compiled Marriage Index, 1600s-1800s; De Steiger. Isabelle. Memorabilia: Reminiscences Of A Woman Artist And Writer. Rider & Co. London, England. (1927): 262.

[83] “A Hindu Philosopher.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) November 23, 1886; “Oriental Theosophy.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) November 28, 1886.

[84] “A Titled Spiritualist.” The Illustrated American. Vol. XIX, No. 310. (February 1, 1896): 155.

[85] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 666. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Camille Flammarion. [7/23/1880.]

[86] Taylor, Eugene. “William James and Depth Psychology.” Essay in The Varieties Of Religious Experience: Centenary Essays. Ferrari, Michel (ed.) Imprint Academic. Exeter, England. (2002): 11-36.

[87] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Vol. III (1883-1887.) The Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 79-86.

[88] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2868. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Louis Olivier. (May 27, 1884.)

[89] Xau, Fernand. “La Théosophie.” Gil Blas. (Paris, France) May 7, 1884.

[90] Barker, A.T. (ed.) Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna; Sinnett, Alfred Percy. The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett and Other Miscellaneous Letters. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. London, England. (1925): 180.

[91] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Vol. III (1883-1887.) The Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 90-91.

[92] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume III. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 98.

[93] “The Monthly Abstract Of What Was Done At The Society’s Meetings. The Browning Society’s Papers, 1881-1884: Part V. (April 25, 1884): 112-124.

[94] “Occasional Notes.” The Edinburgh Evening News. (Edinburgh, Scotland) May 5, 1884.

[95] [William Quan Judge to H.S. Olcott, May 11, 1884] in Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1951.

[96] Judge, William Quan. “H.P.B. At Enghien.” Lucifer. Vol. VIII, No. 45 (July 15, 1891): 359-364.

[97] The Society For Psychical Research. First Report Of The Committee Of The Society For Psychical Research, Appointed To Investigate The Evidence For Marvellous Phenomena Offered By Certain Members Of The Theosophical Society. The Society For Psychical Research. London, England. (1884): [Appendix II] 62-74.

[98] Judge, William Quan. “H.P.B. At Enghien.” Lucifer. Vol. VIII, No. 45 (July 15, 1891): 359-364.

[99] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2905. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Mme. Vera Jelihovsky; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2906. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Mme. Nadeya A. Fadieff.

[100] Page, Norman. An Oscar Wilde Chronology. Springer. New York, New York. (1991): 28; V. P. Zhelihovskaya. “Letters From Abroad.”

[101] “Muscle Reading By Mr. Stuart Cumberland. ” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) May 24, 1884; Dibb, Geoff. “Oscar Wilde and The Mystics: Thought Transference, The Detection Of Crime And Finding A Pin.” The Wildean. No. 42 (January 2013): 82-99; Cumberland, Stuart C. A Thought-reader’s Thoughts. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. London, England. (1888): 280-282.

[102] Leadbeater, Charles Webster. How Theosophy Came To Me. Theosophical Publishing House. London, England. (1930): 23-24.

[103] “Babu Mohini Mohun Chatterji.” Fall River Daily Evening News. (Fall River, Massachusetts) November 29, 1886.

[104] “Courrier Des Spectacles.” Les Gaulois. (Paris, France) May 15, 1884.

[105] Cronin, Charles P. D. & Klier, Betje Black. “Théodore Pavie’s ‘Les babouches du Brahmane’ and the Story of Delibes’s Lakmé.” The Opera Quarterly. Vol. XII, No. 4. (Summer, 1996): 19-33.

[106] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. V. P. Zhelihovskaya Letters (1878-1896.) Bakhmut Roerich Society.

[107] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2970. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Edwin Forbes Waters. (8/5/1884); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2971. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Clara Erskine Clement Waters. (8/5/1884.)

[108] “Vermont Varieties.” The San Francisco Chronicle. (San Francisco, California) September 11, 1887.