Throughout the nineteenth century, policy-makers in Britain maintained that the preservation of the Ottoman Empire was necessary to the balance of European power and was a sine qua non for British interests in India. The image of Turkey as the brave ally of Britain against Russia in the Crimea was actively cultivated. The successive British governments (Whig, Tory and Liberal,) however, impressed upon the sultans a need for reforming the entire structure of Ottoman government. One primary concern was the treatment of the Balkan Christians in their empire.[1] The Ottomans had radically changed in the religious and ethnic demographics in the Balkans in the second half of the fourteenth century. After conquering that region, a significant Muslim presence took root. Turks from Anatolia and Asia Minor were brought to colonize the Balkans to establish a strong Turkish-Muslim base for further conquests into Europe.[2]

Religious strife was enflamed in the Balkans in the summer 1875 by an uprising of Christians Serbs in Herzegovina and Bosnia, known as the Herzegovina Uprising.[3] It began as a response to the Ottoman administrators of Bosnia, the beys (lineage honorific) and aghas (civilian honorific) who ignored the reforms of Sultan Abdulmejid I, and increasingly brutalized their Christian subjects (financially, physically, and spiritually.)[4] By April 1876 another outbreak of violence occurred in the region, and independence movement known as the Bulgarian Uprising.[5] This was concurrent with the outbreak of the Serbian-Turkish Wars, and known collectively as the Eastern Crisis.[6] In the midst of this tumult, in August 1876, Abdul Hamid II ascended the Ottoman throne, assuming the title of Caliph and Sultan at the traditional ceremony of biat.[7]

During the summer of 1876 reports trickled into Britain of atrocities being perpetrated against the Bulgarians by irregular Turkish troops known as the Bashi Bazuk. One such act was known as devshirme (“child/blood tax,”) the Ottoman practice of forced military conscription of Balkan Christian subjects and forcing them to convert to Islam (and undergo a painful circumcision ritual.) These reports were initially dismissed as exaggerations. Benjamin Disraeli, a Jewish man, and Prime Minister of the Conservative British government, labeled the reports as “coffee house babble.” It soon became impossible to dismiss, when it was verified that between 12,000 and 25,000 Bulgarians had been massacred. William Gladstone, a semi-retired liberal British politician, and former Prime Minister, was one of the first to vocalize his opposition to the Ottoman Empire.[8]

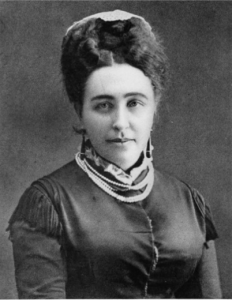

OLGA NOVIKOVA

Madame Olga Novikova (nee Kireeff) (1842-1925) was a Russian woman of aristocracy (both heredity and marriage,) and god-daughter of Tsar Nicholas I. In a lengthened sojourn at Vienna with her brother-in- law, the Russian ambassador, she learned the current business of diplomacy. The three articles of her creed were, she said, those of her country: “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationalism.” She was an eager religious propagandist and formed an alliance with the “Old Catholics” in Europe. Together with her brother Alexander (and many High Church English clergy,) formed a society for the union of Christendom called the Reunion Nationale. When the Serbian-Turkish War commenced, Nicholas volunteered on the side of the Serbians against the Ottomans. He died heroically in battle. It was the death of Nicholas that launched Novikova onto the world stage.[9]

Nicholas Kireeff.[10]

Novikova saw an ally in Gladstone and wrote letter after letter to the former Prime Minister but received no reply. Her letters became increasingly desperate, telling Gladstone that “[if had been in] power no such sacrifice would have been demanded.”[11] Her last letter, “a bitter cry of a sister for a sacrificed brother,” deeply moved Gladstone and he considered what he could do.[12] Catherine Gladstone (William Gladstone’s wife) sent Novikova a letter of “cheer and consolation, saying darkly at the close, ‘Mr. Gladstone will send an answer next week.’”[13] Novikova waited the next week “as a shipwrecked sailor on a craft waits the arrival of the relieving vessel,” but before the week was over, she received a package from Gladstone. It was the answer to her letters, his famous pamphlet, Bulgarian Horrors, and the Question of the East (1876.)[14] One of the strongest protest movements in British history commenced.[15]

Not everyone was pleased with the turn of events. One paper said that “a serious statesman should know better than to catch contagion from the petulant enthusiasm of a Russian Apostle.”[16] Catholic opinion, informed by the Vatican, made it clear that their sympathies were with the Ottomans, whom they believed treated Catholics in their empire with a degree of consideration. For the Catholic world, it was Russia, protector of the Orthodox Slavs, who was the enemy, and Russia’s suppression of the Catholic Polish revolt of 1863 was still fresh in their minds.[17]

London’s Weekly Register and Catholic Standard took a violently pro-Ottoman stance in the summer of 1876, one author argued that the Bulgarians “had brought the atrocities on themselves” by the “burnings, butcheries, ravagings, and other abominations perpetrated by the emissaries of the Revolutionary Committees […]” Thus, Turkish violence was justified as “retaliation.”[18] At this time Novikova felt betrayed by the Jews of Russia, whom she felt “acted against the cause of liberation.” She suggested that the Jews, stimulated by a resentment for the Slavs, whom they regarded as their oppressor, they “adjured to make common cause with the Turks against the Russians.” It was what the contemporary British historian, Edward August Freeman, grimly described as “the sympathy of the circumcision.”[19] This would influence Novikova’s future opinions.

POGROM

On March 1, 1881, Tsar Alexander II of Russia was assassinated by the terrorist group, Narodnaya Volya (“The People’s Will.”) One of the ten members of Narodnaya Volya, Hesya Helfman, was a Jewish woman.[20] Two weeks later, on March 15, the Chief of Police of the Ukrainian town of Elisavetgrad received a strange visitor who claimed to be a retired state councilor. The stranger surprised the police chief with his strong anti-Jewish rhetoric and spoke of an impending pogrom (“violent destruction, wreak havoc”) against the Jews during Russian Orthodox Holy Week as retribution for the death of their beloved Tsar. The stranger left on March 20, but his room was taken up by two more strangers, a man from St. Petersburg and a man from Moscow. These men visited local taverns and fraternized with the clientele.

The Russian right-wing press, particularly Odessa’s Novorossiiskii Telegraf, began an intensive anti-Jewish campaign at this time, spreading rumors that the Christians of Novorossiya were planning a pogrom and stating that these attacks would begin in Elisavetgrad. The Jews of Elisavetgrad asked the police to take action to protect them (while also purchasing arms for self-defense.) On April 10 the governor of Kherson ordered all police district chiefs to exercise heightened vigilance during the Easter holidays. The city administration of Elisavetgrad, subsequently asked the commander of nearby military unit to place some troops as the disposal of the Elisavetgrad’s police chief for the duration of Easter.

The police and the military maintained order in the city, the taverns remained closed, and the Easter holiday passed without incident. The police chief dismissed the military dispatch, and city life returned to normal. No sooner had the military unit been discharged then came twenty young strangers in Elisavetgrad (dressed like their two predecessors from the capitals.) These men mingled with the townspeople in different parts of the city. On April 15, the first market day after Easter, the taverns were again permitted to sell alcohol. In the morning unfamiliar peasants began to arrive, strangely pushing empty carts. At 4 p.m. that day a disturbance broke out in the marketplace. In a Jewish owned tavern, a town drunk broke a vodka glass, prompting the owner to strike him. Other drunk patrons shouted, “the Jews are beating our people,” “the Jews have bribed the police,” and “the Jews have purchased firearms.” Chaos spread to neighboring taverns. About a thousand marketgoers turned into a mob, robbing, and destroying Jewish-owned shops and houses, and discarding their possessions into the streets. At the same time, bands of about forty people sprang up in other parts of Elisavetgrad, instigated by the strangers for the capitals. The mob included women of high society as well as children, so the police avoided using force. Eventually a unit of Hussars were called in to quell the violence, but it was well into the night before the mob was removed from a standoff at the local synagogue. The attacks resulted in the death of an elderly Jewish man.

The next morning another mob began to appear in small groups. They were joined by the unfamiliar peasants who pushed empty carts. (They did not participate in the riots, but they collected the “ownerless” possessions in the streets.) The police, in a combination of ineptitude, drunkenness, and confusion as to what to do, remained passive. It was not until the following day, after the arrival of military reinforcements, that order was restored to the city. The riots of Elisavetgrad directly ignited a total of five pogroms (and one failed pogrom,) occurring in two waves, in different towns. (There were forty-eight incidents of anti-Jewish disturbances in the region that month, but these were not connected with Elisavetgrad.) Curiously, these towns were all located along the railway. In each instance, the violence broke out after the arrival of mysterious strangers who behaved in a similar manner to the strangers who arrived in Elisavetgrad. Who were the mysterious men that presaged the pogroms in these towns? And who was responsible for their activity? It has been suggested that rival merchants planned the attacks, and the mysterious men were highly mobile railroad workers. The Minister of the Interior, Count Ignatiev, would ultimately dismiss the violence as a rural phenomenon, provoked by “Jewish economic exploitation of the illiterate peasantry.”[21]

These attacks were the first significant acts of violence carried out against Jews since 1648 and marked a major turning point between the Russian Government and her Jewish Subjects.[22] (Acts of mob violence known as “Judenhetze,” or “Jew Hunting,” likewise became widespread in Germany at this time.)[23] Unsurprisingly, by the spring of 1881 many Jewish communities within the Pale of Settlement of Russia and Romania began forming Jewish nationalist groups. These organizations would evolve into a movement known as Hovevei Zion (lovers of Zion), or Hibbat Zion. The chief aim of which was to support the establishment of permanent Jewish colonies in Palestine.[24]

Olga Novikova.[25]

While the British press were reporting on the Russian pogroms, Novikova believed “that the treatment of the Jews was being industriously employed as a means of inflaming English sentiment against Russia,” and intervened in the interest of the entente she was trying to secure between Russia and England. Just before the Mansion House meeting, she addressed two letters to the Times, in which she protested against accusation that the Russian Government was guilty of “encouraging the excesses of the social war” in the Jews and their neighbors in the southern provinces. [26] It said in part:

Those Englishmen who are denouncing our Government for the excesses of the social war in the Ukraine have either lost all sense of the ridiculous or else find it necessary to air their indignation at cruelty abroad as a relief after the heroic fortitude with which they have contemplated in silence similar excesses nearer home. Most of the censures which appear in the Press are very ill-formed, and therefore carry no weight. The accident is nearly always mistaken for the essence, and the fact that the sufferers are of Hebrew faith is regarded as proof that the riots are prompted by Christian fanaticism. It would be just as accurate to say that the agrarian outrages in Ireland are protests against the Protestantism of the landlords. We have two kinds of Jews in Russia, the Talmudist and the Karaite. It is only the former who have suffered. Not one hair of the head of a Karaite Jew has been touched, even in the worst riots. Yet the latter reject Christianity as much as the former. Why, then, this contrast? The best reply is to be found in the address sent by the Karaites to the Talmudist Jews. Here is an abstract: ‘Why do the many and discordant elements of Russian society, which have apparently so few interests in common, hate you with such accord and such unanimity? Is it only at hatred of faith? No—your love of money, your insatiable greed, your cupidity, your haste to become rich, your forwardness, your deception, your trickery…your usury, your dramshops, your intermeddling as factors, and your other acts of injustice have embittered the people, roused the envy of the merchant class, and made Jews despised of the nobles […] With well-founded moral convictions and a rational faith, peace will again be restored and enhanced.’ Of course I shall be told these offences do not justify outrages and murder. Certainly not; but they explain what to others would be utterly incredible. The Karaites are Russian citizens of the Hebrew faith. The Talmudists are aliens settled on the Russian soil. It may be wrong to dislike them; but if two and a half million Chinese were monopolizing all the best things in Southern England, and were multiplying even more rapidly than the natives of the soil, perhaps the cry, “England for the English” would not be so unpopular as some of our censors seem to think […] Five years ago the attitude of the Jews throughout Europe […] implied that, after all, bloodshed and violence were mere peccadilloes in their eyes. Fifty times as many men, women, and children were outraged and murdered in one Bulgarian village than all the Jews who have suffered that fate in the whole of Russia in twelve months of social war. But the Jews in that year were not merely silent; they used all their influence to involve England in a war with my country to uphold a system of which Balkan massacres were the natural and inevitable incidents.[27]

This seems to have resonated with Edward August Freeman, who was touring America at the time, and made the connection with the treatment of the Chinese in America. Freeman wrote a letter to Novikova after the Times published her editorial in which he tells her as much (as well as reinforcing the conspiracy of Jewish owned media.) Freeman stated:

The case of the Jews in Russia (as in Servia, Roumania, etc.) is very much that of the Chinese in America, against whom Congress was legislating when I was there; only the President vetoed the Bill. The difference is that the Chinese do not command half the Press of the world, as the Jews do. Therefore when a maddened Russian punches a Jew’s head, it goes forth to all the world as “frightful religious persecution,” while, when a maddened Californian punches a Chinaman’s head, nobody thinks that is because he believes in Buddha or Fo. But mind, while I hold that every nation has a right to legislate against foreigners (Jews, Chinese, or any other) who make themselves nuisances, I don’t go in for outrages done by anybody against anybody.[28]

SOURCES:

[1] Çịçek, Nazan. The Turkish Response to Bulgarian Horrors: A Study in English Turcophobia. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. XLII, No. 1 (January 2006): 87-102.

[2] Eminov, Ali. “Islam And Muslim In Bulgaria: A Brief History.” Islamic Studies. Vol. XXXVI, No. 2/3, Special Issue: Islam in the Balkans. (Summer/Autumn 1997): 209-241.

[3] “The Insurrection In The Herzegovina.” The London Evening Standard. (London, England) August 23, 1875; “The Insurrection In Bosnia And The Herzegovina.” The Morning Post. (London, England) March 6, 1876.

[4] “The Insurrection In The Herzegovina.” Reynolds’s Newspaper. (London, England) August 22, 1875.

[5] Çịçek, Nazan. The Turkish Response to Bulgarian Horrors: A Study in English Turcophobia. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. XLII, No. 1 (January 2006): 87-102.

[6] Calic, Marie-Janine. History of Yugoslavia. Purdue University Press. West Lafayette, Indiana. (2019): 25-37.

[7] Buzpinar, Ş. Tufan. “Opposition to the Ottoman Caliphate in the Early Years of Abdülhamid II: 1877-1882.” Die Welt des Islams. Vol. XXXVI, No. 1 (March 1996): 59-89.

[8] Gladstone, William. Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East. John Murray. London, England. (1876): 13-14.

[9] Tuckwell, William. A,W. Kinglake: A Biographical and Literary Study. George Bell And Sons. London, England. (1902): 90-110.

[10] Stead, W.T. (ed.) The M.P. For Russia: Reminiscences & Correspondence Of Madame Olga Novikoff Vol. I. Andrew Melsore. London, England. (1909): 198.

[11] Stead, William T. “Character Sketch: Madame Olga Novikoff.” The Review of Reviews. Vol. III, No. 14. (February 1891): 123-136.

[12] Tuckwell, William. A,W. Kinglake: A Biographical and Literary Study. George Bell And Sons. London, England. (1902): 90-110.

[13] Stead, William T. “Character Sketch: Madame Olga Novikoff.” The Review of Reviews. Vol. III, No. 14. (February 1891): 123-136.

[14] Gladstone, William. Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East. John Murray. London, England. (1876.)

[15] Rossi, John P. “Catholic Opinion on the Eastern Question, 1876-1878.” Church History. Vol. LI, No. 1 (March 1982): 54-70.

[16] Tuckwell, William. A,W. Kinglake: A Biographical and Literary Study. George Bell And Sons. London, England. (1902): 90-110.

[17] Rossi, John P. “Catholic Opinion on the Eastern Question, 1876-1878.” Church History. Vol. LI, No. 1 (March 1982): 54-70.

[18] Rossi, John P. “Catholic Opinion on the Eastern Question, 1876-1878.” Church History. Vol. LI, No. 1 (March 1982): 54-70.

[19] Stead, W.T. (ed.) The M.P. For Russia: Reminiscences & Correspondence Of Madame Olga Novikoff Vol. II. Andrew Melsore. London, England. (1909): 279-280.

[20] Blech, Benjamin. Eyewitness to Jewish History. John Wiley & Sons. Hoboken, New Jersey. (2004): 208-209.

[21] Pritsak, Omeljan. “The Pogroms of 1881.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies. Vol. XI, No. 1/2 (June 1987): 8-43.

[22] Aronson, I. Michael. “Geographical and Socioeconomic Factors in the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia.” The Russian Review. Vol. XXXIX, No. 1 (January 1980): 18-31.

[23] “Judenhetze.” The Banner of Israel. Vol. V. No. 233. (June 15, 1881): 245-246.

[24] Goldstein, Yossi. “The Beginnings of Hibbat Zion: A Different Perspective.” Association For Jewish Studies Review. Vol. XL, No. 1 (April 2016): 33-55.

[25] Stead, W.T. (ed.) The M.P. For Russia: Reminiscences & Correspondence Of Madame Olga Novikoff Vol. I. Andrew Melsore. London, England. (1909): 182.

[26] Stead, W.T. (ed.) The M.P. For Russia: Reminiscences & Correspondence Of Madame Olga Novikoff Vol. II. Andrew Melsore. London, England. (1909): 278.

[27] Novikova, Olga. [O.K.] “A Russian Reply.” The Bristol Mercury. (Bristol, England) January 19, 1882.

[28] Stead, W.T. (ed.) The M.P. For Russia: Reminiscences & Correspondence Of Madame Olga Novikoff Vol. II. Andrew Melsore. London, England. (1909): 280-281.