PYATIGORSK

They left St. Petersburg on May 8, stopping on the way to see Prince Tyumen eighty miles before reaching Astrakhan. Everyone was delighted to find Elena Pavlovna was already waiting for them there with Nadya. From there, on May 20, they all went together to Astrakhan by water in large boats. Having stayed in Astrakhan for two weeks, they all set off again together on June 9 for Pyatigorsk, since Andrei Mikhailovich also had to go to the Caucasus on business. They traveled a hundred miles along the Kizlyar postal road, turning right into the Kalmyk steppes where their trip took on a very original form. They had to continue our journey on camels, supplied in advance by the Kalmyks for their passage.

The dromedaries were harnessed to the carriages like horses, a pair to the pole. These celebrated “ships of the desert,” so useful in Asian caravans, and hardy in the Arabian deserts, turned out to be the laziest and most unbearable animals in the Astrakhan steppe. Immediately, in harness, they walked with their smooth, prim step for two or three miles, then one camel, without the slightest reason, lay down on the ground, his comrade followed his example, and there was no longer any way to make them get up, except one: to release them from the harness and harness the others, who, having walked two miles, inevitably arranged the same maneuver, which significantly slowed down their journey. (Probably, the camels showed this protest against the harness and did not want to submit to it.) The steppe was a continuous, boundless mass of sand, carried by the wind into high mounds, like moving mountains, from place to place. Against the force of the wind and sand, it was almost impossible to stand on one’s feet. Occasionally, green, or rather, red, bushes would be spotted, of half-dried wormwood turned green. Sometimes there were shallow wells with water so bitter and disgusting to the taste that even the camels refused to drink it. They took with them a few barrels of water as a reserve, but the heat from the sun soon warmed it up so much that it was not fit for consumption. Further along the road, vegetation began to appear, and green grass gradually replaced the yellowness of the sand.

Along the way, they met exiled Decembrists, like Sergei Ivanovich Krivtsov, whose acquaintance would inform a number of subsequent Helena Andreevna’s works.[1] They spent one night in a salt outpost, another in the steppe, and a third in a Kalmyk nomad camp, where the Kalmyks received them very cordially. They even arranged a solemn service in their honor in a kibitka, which replaced their khurul (temple.) About ten and a half gelungs, sitting in two rows opposite each other, with their legs tucked under them, in front of an elevation filled with burkhans (idols), played on pipes of all gradual sizes, from long ones, about one and a half yards, to the shortest ones, about two inches. This music of heterogeneous, thundering, and whistling sounds was sometimes deafeningly sharp, and sometimes quietly rattling; sometimes it cut their unfamiliar ears but taken together, resounding and spreading across the boundless steppe, it made up a strange, fantastic harmony, not devoid of some wild grandeur, which produced a special impression. Walking through the Kalmyk ulus, and settling down for the night in their tents, would serve as inspiration for Helena Hahn’s future stories.[2]

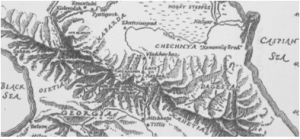

Caucasus c. 1830s.[3]

On the fourth day, they reached the banks of the Kuma, where they found a good rest with all the amenities in the home of the landowner Alexei Fedorovich Rebrov, a famous silkworm breeder.[4] For someone who wanted to get acquainted with a veteran of the Caucasus and beyond the Caucasus, a conversation with him was of great interest and entertainment. Rebrov had once been the head of the chancellery of the first chief in Georgia, after its occupation by the Russians. It was partly because of this that Pyatigorsk became a “spa.” The area of Russian settlement in the Southern frontiers was disease-ridden, with high mortality rates from the plague, malaria, typhus, scurvy, and cholera. This resulted in the spa industry of the North Caucasus. Before it was Pyatigorsk, it was Konstantinogorskaia Fortress, the place where sick soldiers and Cossacks went to bathe in the hot springs under Kalmyk tents.[5]

From Rebrov they went through Russian villages along the Kuma to Pyatigorsk, arriving at Pushkin’s favorite spa on June 16. There Andrei Mikhailovich made several new acquaintances and renewed an old one with Prince Vladimir Sergeevich Golitsyn, a clever joker and a great wit and gastronome whom the family had met back in 1815. (It was his rachki that Ekaterina Vasilyevna Kozhina re-gifted at her ball.) He was a young, handsome hussar at the time, but now he was a very fat general.

Of the new acquaintances, the most remarkable was the old, respected veteran, General Ivan Nikitich Skobelev. He was famous for his bravery, and his exploits in war (which took two of his fingers.) Andrei Mikhailovich met him thanks to Katya, who quite by chance acquired his most friendly disposition. Walking in the garden with the family of Prince Golitsyn and others, she went to get a drink of water from the Mikhailovsky Spring. There was a gentleman among them of Greek extraction who had come from Odessa but was completely Russified.[6] This man served in St. Petersburg in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, wrote in Russian journals and subsequently occupied significant positions in the diplomatic service. In general conversation, he, quite contrary to his title of diplomat (and even just a decent person,) lied in the most tactless way. He claimed to have recently been asked at somewhere if he was Russian. He allegedly answered: “No, and if there was anything Russian in me, I would bleed myself so that not a single drop of Russian blood would remain in me!” To this Katya objected to him: “What a pity that you did not do it right away—in case of insanity, bloodletting can be very useful.” Then a lively argument began, which soon forced the diplomat to silence. The next day, at the waters, General Skobelev, whom Katya did not know, came up to her, took her by the hand and said: “I heard yesterday, young lady, your conversation, and I am so grateful to you for everything you said, there was so much patriotism and truth in your words that I would be ready to do anything for you—and will do for you whatever you want—I will climb the bell tower of Ivan the Great and jump from it; in a word, you can demand from me whatever you want, I will always be completely at your service!” After that, Skobelev constantly showed Katya special attention and did not miss an opportunity to approach her and have a friendly conversation with her.[7]

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Sergei Ivanovich Krivtsov (1802–1864) was a Decembrist who was sentenced to hard labor for four years followed by settlement in Siberia. In 1831he was transferred as a private to the Caucasus where, in the summer of 1837, he met Helena Andreevna. [Gershenzon, M.O. “Russian Woman Of The ‘30s.” Russian Thought. Vol. XII, C. 55 (December 1911.)]

[2] Nekrasova, E. S. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn (1814-1842): Part II.” Russkaia Starina. Vol. LI, No. 9 (September 1886): 553-574; Zhelikhovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn (1835-1842.)” Russkaia Starina. Vol. LII, No. 3 (March 1887): 733-766; Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn, Zeneida R-va.” (1885.) [Preparation of the text and comments by A.D. Tyurikov. Bahmut Roerich Center; Harussi, Yael. “Hinweis Auf Elena Gan (1814—1842.)” Zeitschrift Für Slavische Philologie. Vol. XLII, No. 2 (1981): 242-260.

[3] Lermontov, Mikhail Yuryevich; (tr.) Nabokov, Vladimir. A Hero Of Our Time. Doubleday Anchor Books. Garden City, New York. (1958): Frontispiece.

[4] “[Alexei Fedorovich Rebrov,] a famous silkworm breeder and winemaker, the Caucasian regional leader of the nobility, a writer; born in Moscow on February 21, 1776, died in Pyatigorsk on October 23, 1862 […] In 1827, Rebrov retired with the rank of state councilor and devoted himself entirely to agriculture. He was married to the daughter of cavalry general I. D. Savelyev and received as a dowry the rich village of Volodimirovka, located in the Caucasus; here Rebrov was engaged in sericulture and winemaking. He transformed the salt marshes, marshy and inaccessible lands for cultivation, into mulberry plantations and vineyards by means of canals. All this cost him a lot of work and enormous expenses. He ordered silkworms from China, Arabia, France and other countries. He invented a device for unwinding and splicing silk; he received 5 large gold medals for sericulture; his silk was famous as one of the best in Europe, about which Rebrov was notified by the French Royal Society of Sericulture, and in 1851 he received a diploma with recognition by experts of the London exhibition of Rebrov’s silk as excellent in quality and whiteness. In 1831, Rebrov published articles “On sericulture in Russia” and “On the newly invented silk-winding device in the Caucasus” in The Agricultural Journal, and then almost every year he published his annual reports and articles on sericulture in this journal. On his estate he set up a free school for peasant boys, where they were taught literacy and the rudiments of the law of God and arithmetic in the winter, and sericulture in the summer. In addition, in 1833 he made a one-time contribution to the Moscow Imperial Society of Agriculture, and then contributed money annually for the establishment of sericulture in Moscow. For the same purpose, he annually sent mulberry bushes and seeds from the Caucasus to the Society for free distribution to those wishing to engage in sericulture. He bred up to 40 different types of grapes, including Shiraz (oval, seedless). To make table wine, he invited the winemaker Ango from Burgundy, and to make sparkling wine, similar to champagne, he brought in the Frenchman Tillier, one of the main winemakers of the establishment of the widow Clicquot. Rebrov’s wines were famous not only in Russia, but also abroad.” [Polovtsov, A. A. Russian Biographical Dictionary. Vol. XV: Prittwitz-Reis. Imperial Academy of Sciences. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1910): 530-531.]

[5] Barrett, Thomas M. “Lines of Uncertainty: The Frontiers Of The North Caucasus.” Slavic Review. Vol. LIV, No. 3 (Autumn 1995): 578-601.

[6] Russia was not prepared to exploit the commercial opportunities of the newly acquired southern outlets after the Treaty of Jassy (1791.) With barely any merchant marine, trained sailors, or mercantile houses, Russia implemented a policy of inviting merchants of different nationalities, religious beliefs, and skills to settle the newly founded ports. Foreign merchants arrived immediately to exploit the commercial possibilities offered by the new waterways. Greek colonists settled here in large numbers. [Herlihy, Patricia. “Greek Merchants In Odessa In The Nineteenth Century.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies. Vol. 3/4, Part 1. Eucharisterion: Essays Presented To Omeljan Pritsak On His Sixtieth Birthday By His Colleagues And Students (1979-1980): 399-420.]

[7] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 129-132.