THE ARABAT ARROW

Travels in the colonies began for Andrei Mikhailovich in 1816. His first survey directed him to the Chernigov Province, to the Radichevo Colony, peopled by Tyrolean immigrants. The Hutterites, that is, the people of the Radichevo Colony, originated as a sectarian communistic society in Moravia. Named after their martyred leader, Jacob Huter, they were a part of the Anabaptist movement (which itself was a product of the Protestant Reformation.) Their practice of community of goods began as an emergency measure in the pooling of their possessions when fleeing to Wallachia from Nicolsburg in 1528. It had as its religious basis the words in Acts 2:44-45: “And all that believed were together and had all things common; And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.”[1] In 1772, Field Marshal Pyotr Rumyantsev (Governor of Little Russia) convinced them to relocate to lands he owned in the Chernigov Province. In 1799, according to their wishes, they were resettled on State-Owned lands on the Desna River. It was not dissimilar to the Moravian Colony at Sarepta.[2]

Founded in 1765 by the Unitas Fratrum (Herrnhuter Bruedergemeine, or Moravian Brotherhood) fourteen miles south of Tsaritsyn where the Sarpa emptied into the Volga, the Sarepta Colony evolved into a community that remained an oddity within the Russian Empire. These Moravians were a Protestant sect that developed and spread in Bohemia (Czech Republic) and Moravia during the 16th century. A distinctive feature of the Herrnhuters’ doctrine was the “religion of the heart,” an intimate experience of unity with Jesus Christ as the guardian and savior of the world. Their colony at Sarepta became something of a health resort and was celebrated by Russian high society. As peculiar as their beliefs seemed, they were praised as industrious Germans who miraculously transformed part of the inhospitable steppe into a clean, thriving community.[3]

What made the Radichevo Colony different from the Sarepta Colony, was their insistence on living as one family, “like the Christians of the first centuries of the church.” They renounced all private ownership, devoting themselves entirely to turning the fruits of their labors into the common property of the colony. In this sense, they were not unlike other reformers in the burgeoning “Restorationist” and “Primitive Christianity” movements that arose in other parts of the world. (John Wesley, founder of Methodism, was even in contact with a colony of German Moravians in the United States.)[4] Andrei Mikhailovich admired the Radichevo Colony, especially its novel organization. Johannes Waldner, their foreman at the time, was an eighty-year-old man with a long, gray beard. He was dignified, very pious, and a great fanatic, entirely convinced that his way of life was the true way of practicing Christianity.[5]

In the summer of 1816, Andrei Mikhailovich accompanied Kontenius for the first time to survey the colonies closest to Ekaterinoslav and Molochnye Vody. He realized then the administrative abilities, patience, and good intentions of his respectable mentor. At this time, Kontenius’s main attention was focused on the creation of viable practices of sericulture, horticulture, and Spanish sheep breeding. His work was largely a success, not only in Ekaterinoslav but also in Kherson and along the Molochansky waters in Tauride.

The Chumatsky Tract.

In the autumn of 1816, the Fadeevs went to Crimea for the first time, fulfilling the childhood dream of Elena Pavlovna. She had heard so much about its natural beauty from her grandmother, Elena Ivanovna, who lived in Crimea with Adolf Frantsevich when he fought the Ottomans in the 1770s. The Fadeevs directed their path through the nearest road to Crimea, cutting through the Molokan Colony to the Chumatsky Tract. They continued through the Genichesk Strait and the Arabat Arrow which formed a narrow split between the Sea of Azov and Syvash Lagoons (or “Putrid Sea” as it was more commonly known.) It was a barren, sandy stretch of land barely above sea level, about 70 miles long and 5 miles wide at its greatest width. During strong winds, the waves splashed onto the road. There were, however, good pastures and healthy spring water in three places. Farmsteads were built at these oases and served as refuges for travelers during storms and foul weather. Colonel Fyodor Trevogin, a favorite of Suvorov, was the owner of one of these farmsteads. A brave officer, mutilated with scars and hung with military crosses, he built himself a home in this remote place to find respite after many years of battle. At peace, he nevertheless enjoyed the company of travelers and welcomed everyone with joyful hospitality.

Another resident on the “Arrow,” was a Ukrainian Cossack, who came to Theodosia during the reign of Catherine the Great. He took up philandering and trading in grain, making a decent fortune in the process. When Napoleon invaded in 1812, an appeal was dispatched to everyone to defend Mother Russia. The man went to the commandant and announced that he would sacrifice all his money and possessions and fight the French with his three adult sons. The proposal was accepted. He gave his property to the treasury and went to war with his sons, two of which were killed during in combat. The old man returned home empty-handed after the war. Out of compassion for him, he was allowed to settle on one of the farms on the “Arrow,” where he lived in great poverty. Fortunately for him, a year after his resettlement on the farmstead, the State-Owned land passed from Russia to the Southern Bank. At the same time, Baron Balthasar von Campenhausen, former Governor of Taganrog, was made State Comptroller in the newly formed State Control. He asked Tsar Alexander Pavlovich for leave to get better acquainted with Russia and, for the best possible success in this endeavor, traveled the entire long stretch. He passed through the “Arrow” one stormy October night and was held captive by the inclement autumnal weather. The Cossack provided shelter for Baron Campenhausen, and the two men got into conversation. The old man was clever, and eloquent in his own way. He told Baron Campenhausen all the events of his life that led to his present disastrous situation. Baron Campenhausen said that he would petition the Tsar for a reward on his behalf, but that the outcome would be more favorable if he could somehow make it to Petersburg and ask the Tsar himself. “I will try to present you personally to the Tsar,” said Baron Campenhausen. Remarkably, the Cossack did make his way to Petersburg. He appeared before Campenhausen, who, having reported about him to the Tsar, asked permission to present him. Alexander Pavlovich allowed it. The Cossack, a resourceful man, was not intimidated; he fell at the Tsar’s feet and boldly told his whole story. Baron Campenhausen confirmed the veracity of his stories (having made sure of it with questions and inquiries during his stay in Crimea.) The first thing Alexander Pavlovich did was put a gold medal on the old man.

“What do you want as a reward for your exemplary self-sacrifice during the war?” asked the Tsar.

“I ask that the useless land of the Arabat Arrow be given to me.”

“That is hardly possible,” said Baron Campenhausen, “for although the Arrow’ is now an empty and barren space, it could be very useful in the future for free salt mining.”

They gave the old Cossack money for his return journey and ordered him to appear before Andrei Mikhailovich Borozdin, the Governor of Crimea, with orders for the latter to consider whether the old man’s request could be carried out without harming the public interest. It was indeed possible to carry out his request (under certain conditions regarding the unrestricted salt industry.) Borozdin, however, was governor in name only, and all his affairs were managed by his secretary, Umanets, who led the old Cossack by the nose for a long time, expecting a good handout from him. The old Cossack finally got bored.

“Eh! May the proverb be true,” the Cossack said to Borozdin. “God is high above, and the Tsar is far away.”

This comment found its way to Petersburg. The poor old Cossack would have been left with nothing it seems, had it not been for the arrival of Count Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov when he was appointed Governor-General of Novorossiysk. It was only then that the old Cossack was finally granted some land in the Perekop steppe.

Having completed his official duties in Crimea, Andrei Mikhailovich set off with Elena Pavlovna to travel through Bakhchysarai and Sevastopol along the southern coast. There were no carriageways or roads at the time. Elena Pavlovna did not ride a horse, and Andrei Mikhailovich was admittedly a bad horseman. The weather was beautiful, as per usual on the southern coast in October, therefore they decided to take “à petites journées” on foot. They walked along the seashore, beginning at the St. George Monastery, and continuing through Baydary, Balaklava, on to Sudak. The 100-mile journey took ten days and was an altogether pleasant experience. They took their meals with the inhabitants of the southern coast and had no difficulty in securing accommodation. One such inhabitant was the former

Governor of Crimea, Andrei Mikhailovich Borozdin. Brought up in England, Borozdin received his diploma at Cambridge University, and being a Doctor of Medicine, he was known for his scholarship. As was often the case with scientists, however, he was a bad politician. This is presumably because one is in the habit of fixing problems, while the other is in the habit of causing them. They stayed with the Academician, Peter Köppen, as well as Christian von Steven, the Finnish-born Russian botanist who helped establish the Nikitsky Botanical Garden near Yalta four years earlier.[6] They even enjoyed the hospitality of Pyotr Vasilievich Kapnist, brother of the famed Russian writer, Count Vasily Vasilievich Kapnist. A kind and respectable old man, Pyotr Vasilievich was considered a benefactor to all the poor. He was something of an eccentric, taking 20-mile walks every day. Few would have guessed his storied life of romance. In his youth, Pyotr Vasilievich was known as a big reveler. After retiring from the Preobrazhensky Regiment in 1775, he killed a guard during a duel. To avoid punishment he “wandered about for several years in foreign lands.” First, he went to Holland, then he went to France. This was during the years of the Revolution, and he enrolled in the bodyguard of King Louis XVI. After the French regicide, Pyotr Vasilievich went to Britain and married an English girl. He eventually returned to Russia and bought a small plot of land on the shores of the Black Sea.[7]

The southern coast of Crimea did not yet present to the traveler’s eye either the luxurious palaces or the magnificent gardens that would be built there in the years to come. The Fadeevs would cherish the opportunity to see it in its natural and more or less primitive form. There were still the remains of the Genoese towers that adorned the picturesque shores of Sudak. Andrei Mikhailovich and Elena Pavlovna spent several days in the German colonies near them, in the pleasant company of Baron Alexander de Bode and Reverend Arthur Young. Baron de Bode was the son of French nobility who found refuge in Russia with his family. Being still young when he arrived, he enthusiastically embraced his new adopted homeland.[8] Young was the son of a famous English agriculturalist of the same name. Both father and son owned property in Crimea, the elder Young possessing a considerable estate at Karagoss.[9] The junior Young, like many in these parts, was also an eccentric. He purchased a plot of land with a vineyard, not for winemaking, but to feed grapes to an exotic breed of pigs.

The Fadeevs returned to Ekaterinoslav the same way they came, through the Molokan Colonies. In the coming years, Andrei Mikhailovich would spend a good deal of time among them and would come to admire their way of life. Often living with them for two or three weeks at a time, during the initial construction of houses, outbuildings, and blockhouses. They were likened to the founders of new colonies and towns in North America, and judging by what he read of America, he was inclined to agree. These Mennonites were model colonists and likened to the Puritans and their “city upon a hill.”[10]

A significant event took place in Ekaterinoslav in May 1816. Tsar Alexander Pavlovich’s younger brother, the Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich, passed through the city on his tour across Russia. There was a lot of commotion in the preparations of the nobility, citizens, and officials for the reception of the distinguished guest. Kirill Semenovich Gladkiy, the Governor of Ekaterinoslav was recently dismissed, and the Province was ruled by the Vice Governor, Mikhail Timofeevich Elchaninov, an odd, short-sighted man.

There was still no cathedral in Ekaterinoslav since the Transfiguration Cathedral was never completed. Two wooden churches were the only places of Christian worship. The more impressive of these two, the one that was only old and dilapidated, served the practical functions of a cathedral until a proper one was built. Archbishop Iov preferred another church on the opposite side of the city, the one in which he conducted mass. Archbishop Iov insisted that Elchaninov take the Grand Duke from the bank of the Dnieper to his church, but the Vice Governor, overwhelmed by the occasion of the visit, failed in this instruction.

The day had come when Nikolai Pavlovich arrived in Ekaterinoslav. The twenty-year-old Grand Duke was an unusually attractive lad; tall without being thin and grown straight like a fir tree. He sported the rudiments of mustachios, though his face was youthful, with a finely cut chin.[11]

“Where does His Highness order to take Himself?” Elchaninov asked the Grand Duke.

“To the Cathedral,” the Grand Duke replied.

Elchaninov rode in a droshky to the front of the Grand Duke’s carriage and led the way to the wrong church. It was already evening, the sky was dark, the weather was rainy, and the roads were muddy. Nikolai Pavlovich was very tired from the road. Arriving at the church they found it locked. There was no clergy, no congregants, nothing at all in the way of a reception. Everything was empty and gloomy. The clergy, congregants, and reception were all waiting a mile away at the church of Archbishop Iov. Elchaninov, completely at a loss, sent subordinates to look for the clergy in their homes. Time passed, and they waited for a very long time. Finally, having learned what was the matter, the Vice Governor reported that the Archbishop was waiting in another church.

I wanted to pray to God,” said the Grand Duke, “but I did not see the Archbishop.” He then ordered to be taken to his apartment.

Having waited in the church for six hours with all the clergy and nobility, Archbishop Iov was furious to the extreme. The following day, at the ceremonial performance, the Archbishop was the first to arrive at the hall. When the Grand Duke left his office, Archbishop Iov greeted him.

“Forgive me, Your Highness,” he said, pointing to Elchaninov, “that yesterday, through the stupidity of this gentleman standing here, they took you to an empty church and caused you trouble.”

The Grand Duke smiled and walked away, bypassing Elchaninov.[12]

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

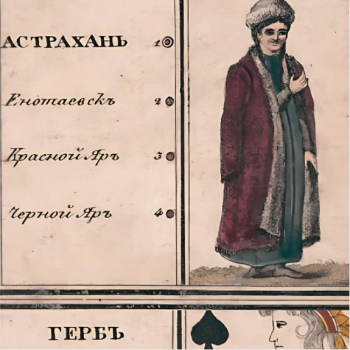

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Deets, Lee Emerson. “The Origin Of Conflict In The Hutterische Communities.” In Social Conflict Papers Presented At The Twenty Fifth Annual Meeting Of The American Sociological Society. University Of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (1931): 125-135.

[2] “Sarepta, so called from the resemblance that Scripture name bears to the river Sarpa, on which it is situated, was first founded by the Moravian Brethren, in the year 1765, in consequence of an edict issued to that effect by the Empress Catharine. Several companies of brethren and sisters having gone out to join the original settlers, the number of its inhabitants soon increased, and, in short period, it became a very flourishing colony. Its valuable mineral spring, which was at the distance of a few versts from the town, proved an additional source of prosperity the number of visitors which resorted thither their health, rendered it necessary to extend establishment far beyond what the Unity projected. They accordingly erected dwelling-houses, mills, tanneries, and distilleries; planted orchards, vineyards, and culinary gardens; and brought into operation an extensive system agriculture. The town is regularly laid out according to the plan of the Brethren’s towns Germany, with wide streets; a fine large square with a fountain in the center; a capacious place worship; the houses belonging to the elders, unmarried brethren, sisters, and widows, and occupied by the different families, together the workshops for the different handicrafts on in the place. Fine tall poplars line the streets and ornament the square; and the vineyards gardens give it an appearance most to the eye that has been accustomed to wander vain in quest of a single bush for hundreds versts in the surrounding steppe.” [Henderson, Ebenezer. Biblical Researches And Travels In Russia. James Nisbet. London, England. (1826): 410-411.]

[3] Kohls, Winfred A. “German Settlement On The Lower Volga; A Case Study: The Moravian Community At Sarepta, 1763-1892.” Transactions Of The Moravian Historical Society. Vol. XXII, No. 2 (1971): 47–99.

[4] Hammond, Geordan. “Versions of Primitive Christianity: John Wesley’s Relations With The Moravians In Georgia, 1735-1737.” Journal Of Moravian History. No. 6 (2009): 31–60.

[5] “Waldner, Johannes Waldner (1749-1824,) born near Villach, Carinthia, of Lutheran parents, with whom he migrated on the order of Empress Maria Theresa to Transylvania in 1755, along with other Lutherans. Here the entire Carinthian exile group turned Hutterite and became the very soul of a revitalization of the brotherhood. In his later years he wrote his recollections, called Denkwurdigkeiten, as a sort of continuation of the old Hutterite chronicle, the Geschicht-Buch. Thus grew a remarkable new book, the Klein-Geschichtsbuch der Hutterischen Brüder […] In 1767 Waldner shared the dramatic flight of the brotherhood across the mountains into Romania (Walachia) and all their subsequent hardships until the Brethren found a new home in Ukraine, first in Vyshenka, later in Radichev. In 1782 he was elected preacher, and in 1794 bishop of the entire brotherhood.” [(eds.) Bender, Harold S; Smith, C. Henry. The Mennonite Encyclopedia: Vol. IV O-Z. Mennonite Publishing House. Scottsdale, Pennsylvania. (1959): 877.]

[6] (Committee Of Ministers.) Statesman’s Handbook For Russia: Vol. I. Eugen Thiele. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1896): 261.

[7] Edgerton, William B. “Laying A Legend To Rest: The Poet Kapnist And Ukraino-German Intrigue.” Slavic Review. Vol. XXX, No. 3 (September 1971): 551–560.

[8] Childe-Pemberton, William S. The Baroness de Bode, 1775-1803. Longmans, Green, And Co. New York, New York. (1900): 272, 278-279.

[9] Alexander, James Edward. Travels To The Seat Of War In The East, Through Russia And The Crimea: Vol. II. Henry Colburn And Richard Bentley. London, England. (1830): 200; Gazley, John G. “The Reverend Arthur Young, 1769-1827: Traveller In Russia And Farmer In The Crimea.” Bulletin Of The John Rylands Library, Manchester. Vol. XXXVIII, No.2 (1956): 360–405.

[10] Staples, John R. Johann Cornies, The Mennonites, And Russian Colonialism In Southern Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, Canada. (2024) 48-76. [Chapter Three: “A Public Life, 1818–1824.”]

[11] Bauer, Karoline. Memoirs Of Karoline Bauer. Robert Brothers. Boston, Massachusetts. (1885): 122.

[12] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 50-58.