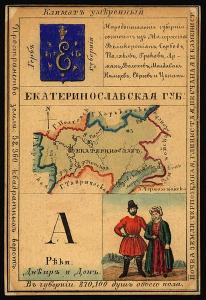

EKATERINOSLAV

At the end of his assignment, Andrei Mikhailovich returned to Nizhny Novgorod for a few days, leaving Elena Pavlovna with her relatives. He intended on procuring a four-month vacation necessary for organizing his affairs. He planned on picking up his wife in Znamenskoye on the way back, then escorting her to Rzhyshchiv, and then head to St. Petersburg where he would once again look for a job near Kiev. Leave was not given without difficulty. Governor Bykhovts, knowing that Andrei Mikhailovich had connections among high society in St. Petersburg, and also knowing that he could not possibly have a favorable opinion about his administration, offered him a managerial position that was soon opening up in the Water Department. “You can earn an income of eight to ten thousand rubles a year in this post,” the governor assured. Andrei Mikhailovich thanked him and politely refused.

After staying with Elena Ivanovna for a month, Andrei Mikhailovich went to St. Petersburg where the Saltykov princes gave him the same warm welcome and readiness to help as his first visit. Prince In the absence of the Tsar, Prince Nikolai Ivanovich Saltykov was the person in charge at St. Petersburg. He invited Andrei Mikhailovich to dine with him twice every week, and there he met all the aristocracy of that time (the princes Kurakins, Dolgorukys, Golitsyns, Count Markov, etc.) Nikolai Ivanovich recommended him to the former Minister of Internal Affairs, Osip Petrovich Kozodavlev. An intelligent man, Kozodavlev was of humble birth, and being not very wealthy, he, for his own sake, faked and pleased everyone in whom he could find patronage and support. (Alexander Pavlovich did not particularly favor him.) Upon the intercession of Prince Saltykov on Andrei Mikhailovich’s behalf, Kozodavlev showed every possible readiness to fulfil his desire. He was transferred and appointed to the foreign office of the Novorossiysk Province (the whole steppe between the Black Sea and the Azov Sea.) The salary was 800 rubles per year, twice as much as he was making in Nizhny Novgorod.

Upon his return to Rzhyshchiv, Andrei Mikhailovich told Elena Pavlovna of his appointment. Though the family wished it was somewhere closer to Kiev, they were nevertheless pleased with an arrangement in Ekaterinoslav.[1] The Fadeevs soon went to Ekaterinoslav to purchase a house, after which Elena Ivanovna would move in with them in the springtime. Securing a property was more difficult than they imagined. They would eventually find a place with a garden and all the amenities they wanted, meeting a few interesting landowners along the way. Two such landowners, Starago and Leventsa, were particularly memorable. Starago, an honest, simple-minded man, had a small village on the banks of the Dnieper, in a good location 40 miles above Ekaterinoslav Starago told Andrei Mikhailovich that he was only selling the village because of his violent neighbor, Soshin, a former Hussar. The noise from the Soshin and his dogs kept the old man up all night and day. Remembering the proverb: “Don’t buy a village, buy a neighbor,” Andrei Mikhailovich politely declined. Leventsa’s property was also 40 miles from Ekaterinoslav, but Leventsa did not truly want to sell his property and set his price prohibitively high. His goal was to lure people to his property so that he might learn the latest society gossip.

The road from Kremenchug to Ekaterinoslav was a little over 90 miles, with five villages spread out at even intervals. Each of these villages had all the resources for steppe farming and all the small comforts for the contentment of the villagers. At that time, the necessities of life were very cheap in this region, especially in the steppe settlements remote from postal roads (through which Andrei Mikhailovich often passed to survey the colonies.) Once, when changing horses, the attendants only charged ten kopecks for a lunch which consisted of delicious borscht with pies, roast pig, porridge with cream, and watermelon.

Ekaterinoslav itself occupied an unlikely position in the mountains. Founded in 1787 by Catherine the Great on the site of a Cossack village, Ekaterinoslav was more like some kind of Dutch Colony than the governorate of Province. A single main street stretched for several miles (two hundred paces wide,) with plenty of space for gardens and vegetable patches, and for livestock to graze (which the residents took full advantage of without the slightest hesitation.) Harassed for centuries by raiding Tatar hordes from the Ottoman Empire, one of the most valuable achievements of Catherine the Great, was Russia’s conquest (and after 1768) assimilation of the Southern Frontiers. The Empress and her advisors were keenly interested in the rapid settlement and economic development of the “virgin lands” of the south.[2] Prince Grigori Potemkin, the Ekaterinoslav’s first Governor-General (and the de facto Viceroy of Southern Russia,) had big plans for the city, envisioning it as the “Athens of Southern Russia,” and Russia’s third capital, “the center of the administrative, economic, and cultural life of southern Russia.” The autocracy spared no expense in infrastructure and municipal development. The foundations for the first buildings, the Potemkin Palace and the Transfiguration Cathedral were a testament to that ambition. The latter building, modeled after St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, was symbolic. It was not simply an acknowledgment of the Transfiguration of Christ, but also the Enlightenment principles responsible for the science of terraforming which “transformed [the] barren steppes into a bountiful garden, from a habitat for animals into a favorable haven for people flowing from all countries.”[3] After the death of Potemkin in 1791, Ekaterinoslav became a sleepy provincial center, with Tallow melting being the city’s leading industry. By 1795 the only inhabitants in the city were a few Government officials, some soldiers, and a handful of peasants.[4]

One of the first things that Andrei Mikhailovich and Elena Pavlovna did, was explore the ruins of the Transfiguration Cathedral and the Potemkin Palace. All that remained of the former, was the altar and some crumbling stones. As for the latter, it was apparent that the roof of Potemkin Palace was badly damaged. There were no windows, no doors, and not even a guard. The Potemkin Archive Room was littered with documents. Out of curiosity, they rummaged through the mass of papers and found interesting draft letters written by Prince Potemkin to various correspondence. Though these papers contained many curious things, within a few short years they would be little more than scraps that speckled what remained of the garden

Regarding the spiritual hierarchy at the time, the diocesan priest was Archbishop Iov. He was a remarkable person, not because of his arch-pastoral virtues, but because of the originality of his adventures. Born with the surname Potemkin, he was originally a nobleman from Smolensk, and the cousin of Grigori Potemkin. He was a dashing cavalryman in the military in his youth. After killing a colleague in a duel, he fled to Moldavia and became a monk where and lived in a monastery in the mountains for quite a long time. When he learned that his cousin had been elevated to the rank of favorite of Catherine the Great, and leading the army on the Turkish border, Iov left the monastery and went to Potemkin (who graciously accepted him under his protection.) Iov was soon promoted to Archimandrite, and subsequently appointed suffragan bishop in the newly established Ekaterinoslav Diocese. Iov was then transferred to Minsk, where Tsar Pavel Petrovich liked his service and gave him the Alexander Ribbon. Iov remained in Minsk for some time, and in 1811 he was transferred to Ekaterinoslav as an Archbishop. His lifestyle was more ascetic; he fasted to the point of exhaustion, but at the same time he fought with his subordinates and servants. He hoarded and saved money, which he gave out as loans to high-ranking officials (often irrevocably.) Inside his house, he lived a reclusive life, but in the outside world he flaunted carriages and expensive horses (which he cared about more than his flock.) In contrast to Archbishop Iov, there was Archimandrite Macarius, a true monk full of Christian virtues and deep knowledge. Naturally, two such disparate personalities could not get along together for very long. Macarius was transferred to the Altai Mission, and Archbishop Iov remained in Ekaterinoslav.

The rest of society in Ekaterinoslav (besides two or three individuals) was very primitive. Prosperous landowners who lived in the city were almost all members of the nobility or those who reached significance in their condition. The treatment of many landowners with their peasants and servants was most inhumane; one landowner, for example, flogged her people with her own hands until they were half dead. Such barbarity, however, was not limited to the Provinces. There was a famous case in St. Petersburg in 1803. The poor widow of some official was forced to mortgage one of her peasant Souls to a woman of nobility named Rachinskaya. This Rachinskaya tortured the hapless peasant woman with all manners of cruelty. One day Rachinskaya pushed the servant with such force that the woman stopped breathing. Rachinskaya, panicking, tried to dispose of the body by chopping it up and burning the remains. The other servants grew suspicious and notified the authorities. When the police arrived to investigate, they found the partitioned corpse underneath Rachinskaya’s bed.

The governor of Ekaterinoslav at the time was Kirill Semenovich Gladkiy, the son of a simple Ukrainian peasant.[5] Having learned to read and write, he rose in rank in a few decades from clerk to governorship through obsequiousness, achieving the patronage of his superiors. The bureaucrats, almost all of them, were of the same origin and, naturally, subservient to Gladkiy. Their lifestyle was most disorganized; gluttony, drunkenness, idle chatter, and gossip occupied all of their free time. The merchant class consisted of several wealthy people, small traders, and tradesmen, with a small number of Jews included in the admixture.

The Governor-General of Novorossiysk was the Duke de Richelieu, a remarkable statesman who attended the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The most respectable man in Ekaterinoslav, however, was Andrei Mikhailovich’s superior, State Councilor Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius, chairman of the Office of Foreign Colonies, was the most respectable person in Ekaterinoslav, He was, undoubtedly, one of the most trustworthy people Andrei Mikhailovich had ever known, and one of the few foreigners who brought significant benefit to Russia in the career which he served. Kontenius, born in Silesia in 1749, was the son of a poor Westphalian pastor, having completed his education at the university he came to Russia at the age of 25, became a teacher in a noble house, and in 1785 entered the Russian state service. A Board of State Economy, Guardianship of Foreigners, and Rural Husbandry was established in 1797 to promote and administer agriculture and industry in the colonies. Kontenius was appointed to investigate the condition of all foreign colonists in Novorossiya, and since 1799 managed the colonies in the Novorossiysk region (Ekaterinoslav, Tauride, and Kherson.) He worked on the organization and welfare of these colonies tirelessly and with boundless energy, and (as much as possible given the obstacles he encountered,) he achieved his goal. When the Board established an Office of Guardianship of New Russian Foreign Settlers in July 1800, Kontenius was appointed the Chief Judge and stationed at the main office in Ekaterinoslav. Between 1803 to 1805 Kontenius was occupied with the settling of many foreigners (German, Bulgarian, Greek, Swedish, and French,) in South Russia (a total of 120 villages in the regions of Odessa, Crimea, and along the Molochna River.) Kontenius established new agricultural programs in the colonies and was interested in sheep breeding as well as fruit cultivation, silk culture, and the wine industry.[6]

The main subject of the effective management of the colonies, the arrangement of settlers, and the introduction between them of various new branches of economy of the region were separated from the department of the office, and entrusted to the direct management and management of Kontenius. This order gave the venerable old man the opportunity to assist in the improvement of the German colonies according to local circumstances in all provinces of the Novorossiysk. These several families of German colonists were divided according to their religion, Mennonite, Lutheran, and Catholic.

In the estimation of Andrei Mikhailovich, the Mennonites were of better morality, unanimous, and more fond of order than all the other German colonists and were therefore more inclined to order in all economic forms. The resettlement of Mennonites to the Novorossiysk Province, which began under Empress Catherine in 1787, resumed and continued throughout the reign of Alexander Pavlovich. Having moved from Prussian possessions, their settlement was concentrated in the Ekaterinoslav and Tauride Provinces, along the Molochnye Vody. Other colonists came from all the German countries, almost all of them in great poverty. The prevailing opinion was that the founding and spread of German colonies in Russia was a mistake by the government since this caused damage to Russian farmers, depriving them of a livelihood as the population and scope for resettlement multiplied. Andrei Mikhailovich did not agree with this opinion.

In terms of the vastness of Russia, the occupation of colonists was about 1,200 square miles of land, which did not constitute a significant reduction in the means for allocating lands to the offspring of native villagers. (The government acted very wisely, however, by retracting exemption from military service from the number of benefits granted to foreign settlers, as that advantage aroused a great deal of commotion among the Russian villagers neighboring the German colonists.) The government did not have direct financial rewards from their resettlement, and large benefits were given to the settlers (especially the Mennonites.) However, the German colonists for Russia were not useless, as they introduced various branches of economy and industry and the very example of their economic structure. Their example, no matter how much the public argued about it, had slowly influenced not only Russian villagers, but even the Muslim ones (as evidenced by the Nogais in the Crimea, and the Tatars in the Transcaucasian region,) who adopted German agricultural and architectural techniques.

Of the more “charismatic” groups, there were the Molokans (“Milk-drinkers,”) and the Doukhobors (“Champions of Spirit,”) who were part of the broader community of raskolniki (“schismatics”) in the province. First appearing on the scene in the mid-eighteenth century, the Doukhobors as a movement properly began in 1740 when a former sergeant in the Prussian army expatriated to Kharkov and preached revolutionary ideas similar to English Quakerism. He taught the equality of man, the uselessness of public authority, and a belief that one could be in direct communion with the divinity “by aid of the spirit which dwells in all men.” The Molokans, hailing from Tambov, were founded twenty years later, in the 1760s, by a peasant laborer named Oukleïne. Inspired by both Doukhobor and English Protestant teachings, the Molokans owed their name to the fact that they drank nothing but milk. Expounding upon the principles of liberty professed by the Doukhobors, they taught that “where the Holy Ghost is, there is liberty,” and believing the Holy Ghost to be found within themselves, they had little regard for temporal laws or government.[7] Andrei Mikhailovich had encountered both communities while administering the frontiers, and some of his experiences were quite humorous. Some of the raskolniki, for example, had refused to accept the cultivation of the potato (something of a novelty in Eastern Russia,) believing the “accursed root” to be evil (as it was not mentioned in the Bible.) Andrei Mikhailovich, wishing to introduce the useful tuber to the region, was compelled to resort to guile. Inspired by a similar scheme by Frederick the Great, he planted potatoes in an enclosed garden and announced the harshest penalties for whoever touched even one potato. The lure of forbidden fruit was not to be resisted by the raskolniki, and potatoes soon spread far and wide through southeastern Russia.[8]

Then there were the Bulgarian, Jewish, and Russian colonies. The Bulgarians began to move to Russia in 1803 and were settled, for the most part, in the areas of Odessa and Bessarabia. (At the end of the Russo-Turkish War, according to the Bucharest Peace Treaty, the lands of eastern Moldova, “Bessarabia,” went to Russia, and intensive settlement of the region soon began.) They were a hardworking people with good morals, but they were essentially of little use to government coffers (at least in the first decades of their settlement in Russia.) Although they sold a lot of wheat (which at that time was of great value in Russian ports on the Black Sea,) they either buried their proceeds in the ground or sent it back to Turkey, without improving their lifestyle at all.

The Jewish colonies were established in the Kherson Province. The reason for this was the desire of the government to “reduce their harmful numbers in the Polish provinces and direct their activities to more useful work.” This plan did not go as the government had intended. With few exceptions, according to Andrei Mikhailovich, the Jews settled in the new lands without any intention of entering new lines of work, rather they took advantage of the resettlement benefits, and continued their previous way of life and occupation. They found a profitable source of food and income by hiring workers from neighboring Russian villages to till the abundant lands allocated to them.

Ekaterinoslav.

The Russian settlers who left the Smolensk Province (and Belarusians of the Mogilev Province) were transferred due to the extreme scarcity of land. Andrei Mikhailovich found them to be in the most pitiful condition. Withdrawn from the Bobyletsky Starostvo to clear space for military settlements, they were installed on a waterless and barren steppe near Nikolaev. Prince Golitsyn decided to establish (in the heat of his pious aspirations) in Ekaterinoslav Province near Mariupol another fantastic colony. He imagined that it would be very soul-saving and useful to establish a society of “Israeli Christians.” For this purpose, he decided to take over a thousand square miles of the most fertile land near the Sea of Azov and proposed to install there, Jews converting to Orthodoxy. Greater benefits were given to them, and a manager was appointed over them with a greater allowance. (The project would last only twenty years before collapsing with only one family remaining.)

All things considered, Andrei Mikhailovich was happier to work in this new line of service than in the Nizhny Novgorod provincial government. There was plenty of useless paperwork, formality, and disorder (especially in the course of accounting,) but there was also less chicanery and bribery. Unfortunately, Elena Pavlovna’s health began to deteriorate, albeit slowly and slightly. Dr. Karl Ivanovich Rode, the able doctor of Ekaterinoslav, advised her to be more cautious of harmful influences.

-

- NOVOROSSIYA

- The Arbiter Of Europe’s Destiny.

- The House Dolgorukuy

- Madame Krüdener

- Ekaterinoslav

- The Arabat Arrow

- The Mystery Of General Inzov

- The Doukhobors

- Pushkin

- Chuguev Military Settlement

- “The Blessed”

- The Decembrists

- Penza

- Independence

- Last Words Of Samuel Khristianovich Kontenius

- “Amid Coffins And Desolation”

- Rusalka

- Dead Souls

- Secret Passages

- Astrakhan

- Nevsky Prospekt

- Kalmyk Ulus

- Love And Ambition

- Duellistes

- Pyatigorsk

- A Heroine Of Our Time

- Winter Palace

- Zeneida R-Va

- Steppes

- Letter To Natalya

- Fire And Ice

SOURCES:

[1] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 39-50.

[2] Duran, James A. “Catherine II, Potemkin, And Colonization Policy In Southern Russia.” The Russian Review. Vol. XXVIII, No. 1 (January 1969): 23-36.

[3] Potemkin, Grigori. “Outline Of The City of Ekaterinoslav.” October 6, 1786.

[4] Wynn, Charters. Workers, Strike, And Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend In Later Imperial Russia 1870-1905. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (1992): 24-30.

[5] “Gladkiy , Kirill Semenovich , actual state councilor, Kherson and Ekaterinoslav governor, born in 1756 or 1759 (according to the service list in 1791 he was 32 years old), came from a poor noble family (according to AM Fadeyev, he was the son of a simple Little Russian peasant). Not having received a proper education, he owed his rapid promotion only to his natural intelligence and excellent talents (AM Fadeyev gives a different explanation for the reasons for G.’s career success). Having begun his service on May 10, 1771, in the Dnieper pike regiment as a corporal and having been promoted to ensign on September 27, 1782, he then transferred to civil service to the position of secretary of the 1st department of the Ekaterinoslav provincial magistrate with the rank of provincial secretary (March 15, 1784). Promoted to collegiate secretary on September 12, 1785, G. was transferred as an assessor to the Ekaterinoslav Criminal Chamber on August 28, 1790, and promoted to collegiate assessor in 1791. In 1795 he was appointed an adviser to the Novorossiysk provincial government; in 1796 he was promoted to court adviser, in 1799 to collegiate adviser, and in 1800 to state adviser. In 1802 G. was appointed chairman of the Slobodsko-Ukrainian Criminal Chamber; in 1803 he was transferred as chairman of the Kherson Criminal Chamber, and in 1804 he was promoted to actual state adviser. In 1805 he was appointed civil governor of Kherson, and in 1808 of Ekaterinoslav. On January 22, 1816, G. was dismissed from his post and assigned to the Heraldry; in 1819, due to poor health, he retired completely. In the last years of his life, G. suffered from an incurable disease. He died on December 27, 1831, in Ekaterinoslav. He was a knight of the orders: St. Anne, 1st class (1807, with diamonds, 1811) and 2nd class (1805) and St. Vladimir, 2nd class (1812) and 4th class (1794). In 1791 he was included in the 1st part of the genealogical book of the Ekaterinoslav viceroyalty.” [Polovtsov, A. A. Russian Biographical Dictionary. Vol. V: Gerbersky-Hohenlohe. G. Lissner and D. Sovko. Moscow, Russia. (1916): 246.]

[6] Huebert, Helmut T. Mennonites In The Cities Of Imperial Russia: Vol. II. Springfield Publishers. Winnipeg, Canada. (2008): 143.

[7] Hardwick, Susan W. “Religion And Migration: The Molokan Experience.” Yearbook Of The Association Of Pacific Coast Geographers. Vol. LV (1993): 127-141.

[8] Johnston, Charles. “Madame Blavatsky’s Forbears.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXX, No. 1 (July 1932): 12-16.