PANIKHIDA

June 1842.

A month or two after arriving in Odessa, Helena Andreevna announced to the girls that their relatives were coming to visit from Saratov. Her health was oscillating. She recovered for a bit, only for her health to decline once more, and just when things looked desperate, she suddenly came back to life and was cheerful, even. On her good days, she was busy, looking for an apartment where everyone, Dede Andrushka, Baba Lena, the whole family, could fit spaciously and comfortably. Such an apartment was finally found, a little far away perhaps, but Helena Andreevna was pleased with the arrangement.

It was far away from dust, far away from the sound of carriages and noise. At this apartment there was a garden, a planted yard, rather, and from its vantage, one had a spectacular view of the Black Sea. Vera absolutely loved looking at the boats rocking on the waves, quickly cutting through them. There were multi-story barges with white-winged sails inflated by the wind like bubbles, and beautiful steamships, above which was black smoke, and below, on the waves, white foam from the wheels, spreading out like silvery lace. On dark evenings, fiery tails of sparks spread behind the steamships, and they all glowed with bright, multi-colored lights from hatches and lanterns, beautifully reflected in the dark sea.

Helena Andreevna’s illness rarely allowed Antonia to leave her now, but sometimes she came to sit with Vera and admire the sea. There were many subjects of conversation! The sun, descending to the golden-red clouds, left behind the purple and gold sea. The bright moon that silvered the entire sea, and scattered its rays over small ripples, then fell into the depths in one solid shining column, cutting off the entire bay. The sky, and the earth, and the sea—everything around Vera tirelessly asked her a host of questions. Vera was accustomed to turning to Antonia for the solutions. Sometimes Antonia talked to her willingly; but more often she listened absentmindedly, deep in thought. More than once, Vera caught her tears, no matter how imperceptibly she tried to wipe them away.

“Pourquoi pleurez vous, Antonie?” asked Vera.[1] “I know!” she said, immediately answering herself. “You are crying because mamochka is sick.” Her heart felt so heavy, and she began to cry with Antonia.

“Oh! Que je voudrais que votre grand-maman vienne plus vite!” said Antonia, hugging Vera tightly.[2]

Vera wanted Baba Lena there with them as well. They could not wait for the arrival of their relatives. They knew that Helena Andreevna would recover, and everything would get better once the family was reunited. Looking at Helena Andreevna, how she changed every day, losing weight and weakening, Vera often thought and, although she did not have any clear concept of death, was unconsciously frightened and cried. Once, when they did not see their mother all day, Vera sat at the door of her room and did not want to have dinner, drink tea, or go to bed until they let her in to look for herself. Her mother lay pale and weak in bed, but she smiled at Vera and pulled her towards her. After kissing her, Vera laid down at her feet on her bed and fell asleep.

The days were more frequent when they were not allowed into Helena Andreevna’s room, and she herself had not left it for a long time. They saw doctors walking in and out of her with serious faces. Despite all the care and efforts of Dr. Gano (who was famous at that time in Odessa,) she became worse every day, especially from bloodletting, which the medicine of that time strongly believed.[3] The girls eagerly listened to the conversation of the grownups, but everyone fell silent when they saw them, and they, like real children, often had fun and forgot their grief and fear for their mother. Suddenly, one wonderful spring day at the end of May, their long-awaited, dear relatives arrived from Saratov; Baba Lena, Dede Andrushka, Aunt Katya, Aunt Nadya, and Uncle Rostislav, who was just promoted to officer.[4]

Helena Andreevna aroused the hopes of those who loved her with her calmness, and she, in fact, did feel much better. Clear, serene days arrived! The children’s happiness knew no bounds. Vera was constantly triumphant! In the morning, she woke up with the thought of her happiness; that there, with her, were all those whom she loved, especially her kind, incomparable Baba Lena, and her days passed in continuous fun. There was no mention of lessons! As soon as Baba Lena arrived, she announced that there were no lessons in the summer. Their day began with games in the garden, walks on the boulevard to the seashore, or to the shops, from where they always returned with toys and delicacies—just like in Saratov! They went swimming almost every day, and from then on Vera fell in love with swimming in the sea more than any other pleasure. How fun it was to lie near the shore on the wet sand and collect shells and colorful pebbles, waiting for a transparent, seething wave to rush in, lift her lightly, and throw her two or three steps forward, filling everything with white effervescent foam. To feel the stormy waves pass, jump up and run after it along the open shore and lie down again and wait, frozen, for a new surf, and look back in horror at the menacing wave approaching, although knowing perfectly well that it would not drown her, but only lift her off the ground and gently carry her back to her previous place. She would catch glimpses of shiny jellyfish, transparent as glass, blue-green shrimp, crayfish or an ugly black cuttlefish spread out! She could not see when Baba Lena or aunts swam far away, but knew they were brave, and loved to swim. Aunt Nadya began to teach the Hahn sisters. The swimming lessons with Lelya were excellent, but Vera did not want to hear! Vera liked swimming in her own way much more, that is, lying by the shore, holding onto the ground, and waiting for the surf. She collected so many “jewels” at the “bottom of the sea” that she had entire collections of shells, herbs, and colorful stones at home. Sometimes they would come back tired from swimming, but so strong and healthy at the same time. The tea table would already be set on the balcony or in their large, bright room. Helena Andreevna would sit in a large chair, smiling from a distance.

“How was your walk?” Helena Andreevna would ask. “Who did you see? Did you swim well?”

Chatting merrily, the girls would drink tea; and sit down on Baba Lena’s lap (despite Antonia’s exclamations that “it’s a shame, that it’s hard for grandma, sit comfortably next to her.”)

“When Mamochka gets better,” Baba Lena would quietly say, “we will all go to my village, not far from here. Let’s live there for a while. We’ll catch crucian carp in the pond, pick strawberries, and make jam. God willing, Mamochka will completely recover and we’ll all go back to Saratov! Our dear dacha has been waiting for you for a long time! How happy Klava Grechinskaya and Katya Polyanskaya will be to see you! They will come running and bring all their dolls!”

This happy time, given to them by God before the greatest misfortune, the eternal separation from their dear mother, was like a golden dream before the end of childhood.[5]

Five days before the end, Helena Andreevna felt so much better, that she went out into the living room to see the Shemiots. Taking advantage of this improvement, which was considered the beginning of recovery, Dede Andrushka and Baba Lena decided to go to their suburban estate. How amazed they were when they returned two days later and heard that Helena Andreevna was worse again! Lelya and Aunt Katya were about to go to an all-night vigil on the evening of June 24, 1842, when they were stopped with news that Helena Andreevna was very ill. Thirty minutes later, Helena Andreevna died in her mother’s arms. Despite the prolonged suffering, she did not seem exhausted by the disease, and in the coffin, she was even striking in her appearance. It seemed that she died suddenly, so little did the disease change her beautiful face.

Though Vera loved her mother dearly, her death did not upset her so much as it puzzled her, for she had never seen a dead person before. She was told to kiss her mother’s hand, which she did, though it felt as though she was kissing something alien, something foreign to her, not her mother at all. It seemed to her that her sweet, dear mother, over whom she cried so often knowing that she was sick, who just the day before was caressing her and looking at the family with such love, had simply gone somewhere else for a while. It was only temporary, that’s all, she would return soon, and things would go on as they had before! She did not understand that things would never go back to the way it was before, that her mother was gone forever, and never coming back. She was calm and did not bother poor Baba Lena, Antonia, or her aunts whom she felt very sorry for because they cried so bitterly. Although she did not quite understand their grief, seeing their tears, she cried with them.

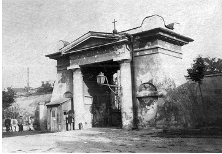

During the Panikhida (Service of the Dead,) there were candles, incense, and chanting.[6] “This is just like church,” she told Lelya. A white marble column, crowned with a decorative urn, was placed at the very entrance of the Odessa Cemetery, as a monument to Helena Andreevna. Around the urn, there was an inscription from her novel, A Vain Gift, which read: “The Power Of The Soul Has Vanquished Life.” Beneath it the words: “Helena Andreevna Hahn. Born January 11, 1814. Died June 24, 1842.”[7]

The City Cemetery, Odessa.

The full realization of the terrible loss came to Vera after the funeral when the family returned from the cemetery to an empty house. Amidst the heavy sadness and tearful caresses of her loved ones, Vera looked back, as if expecting something, and quietly made her way into her mother’s empty bedroom. Not only was her mother not there, the bed on which she had been lying had been removed. Her mother was no longer there. Her mother was in the ground. She threw herself on the chest of dear Baba Lena.

“What does this mean?” she desperately asked. “Where is my Mamochka?! Why did we do this? Why did we put her in the ground?!”

For a long time, no effort by the grownups could calm her down. She kept wanting for her mother to return.

“God took her,” they said. “He called her to Himself!”

“Why? What does God need her for?”

“Verochka—”

“But why?” she screamed. “Tell Him to let her come back! Tell Him to let her live with us! Oh! What terrible days have come here!”

Vera was so exhausted during her last days in Odessa. At night she was plagued by nightmares and fleeting visions of her mother.

She saw her mother—she was there with her, hugging and kissing her, and then she would vanish. She felt feverish and delirious, and again she imagined her tall gray monk, whom she had always seen in a painful delirium since early childhood. In vain she drove him away, angry and frightened by his raised hand. Antonia already knew that during delirium Vera always dreamed of the same “gray man,” whom Vera called a monk. She calmed Baba Lena down by spending days and nights with her over Vera, as only the two of them could calm her down.

The long distracting journey from Odessa to Saratov helped the children more than any medicine ever could.[8]

-

- MOTHERS & DAUGHTERS

- A LANTERN

- CHRISTENING OF THE DOLL

- DASHA & DUNYA

- GRUNYA

- NANNY NASTYA

- NANNY’S FAIRYTALE

- CONFESSION

- IN THE MONASTERY

- PREPARATIONS FOR THE HOLIDAY

- EASTER

- THE DACHA

- THE MELON POND

- MIKHAIL IVANOVICH

- THE WARLIKE PARTRIDGE

- LEONID

- NEW WINTER

- HISTORY OF BELYANKA

- THEATRES AND BALLS

- YOLKA

- REASONING

- ROAD

- CAMP

- IN NEW PLACES

- THE GRAY MONK

- VARENIKI

- THE TRIP TO DIKANKA

- WHAT HAPPENED IN THE DOLL HOUSE

- ANTONIA’S STORY

- “A WINTER EVENING”

- THE BLACK SEA

- CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

- PANIKHIDA

- PRINCE TYUMEN

SOURCES:

[1] [Fr. “Why are you crying, Antonia?”]

[2] [Fr. “Oh! I want your grandmother to come quickly!”]

[3] Nekrasova, E. S. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn (1814-1842): Part II.” Russkaia Starina. Vol. LI, No. 9 (September 1886): 553-574.

[4] Zhelikhovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn (1835-1842.)” Russkaia Starina. Vol. LII, No. 3 (March 1887): 733-766; Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Pt. I.” Lucifer. Vol. XV, No. 87 (November 15, 1894): 202-208; From a draft of Chapter II in Vera Petrovna Zhelihovskaya’s “Radda Bai.” (1892) [Bakhmut Roerich Society.]

[5] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. How I Was Little. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 262-269.

[6] Panikhida, the Service of the Dead in the Russian Orthodox Church, traced its origins to the Desert Fathers. Evening matins and mass were performed every day for forty days after the death (for those whom circumstances permitted.) It was believed that the soul lingered on earth (and given a tour of Hell) before ultimately going to heaven (hopefully,) a process which was facilitated by prayerful intercession of clergy and loved ones. Special requiems were sung on the ninth, twentieth, and fortieth days, over the grave of the deceased, during which time priests were generally entertained as on the day of the funeral, and alms were distributed to beggars. It was believed that the Angels themselves explained to St. Macarius of Alexandria how to conduct the elaborate rite: “When, on the third day, the body is brought to the Temple, the Soul of the dead man receiveth from his Guardian Angel relief from the grief which he feeleth at parting from his body. This he receiveth because of the oblation and praise which are offered for him in God’s Church, whence there ariseth in him a blessed hope. For during the space of two days the Soul is permitted to wander at will over the earth, with the Angels which accompany it. Therefore the Soul, since it loveth its body, sometimes hovereth around the house in which it parted from the body; sometimes around the coffin wherein its body hath been placed: and thus it passeth those days like a bird which seeketh for itself a nesting-place. But the beneficent Soul wandereth through those places where it was wont to perform deeds of righteousness. On the third day He who rose again from the dead [Christ] commandeth that every Soul, in imitation of his own Resurrection, shall be brought to heaven, that it may do reverence to the God of all. Wherefore the Church hath the blessed custom of celebrating oblation and prayers on the third day for the Soul. After the Soul hath done reverence to God, He ordereth that it shall be shown the varied and fair abodes of the Saints and the beauty of Paradise. All these things the Soul vieweth during six days, marvelling and glorifying God, the Creator of all. And when the Soul hath beheld all these things, it is changed, and forgetteth all the sorrow which it felt in the body. But if it be guilty of sins, then, at the sight of the delights of the Saints, it beginneth to wail, and to reproach itself, saying: “Woe is me! How vainly did I pass my time in the world! Engrossed in the satisfaction of my desires, I passed the greater part of my life in heedlessness, and obeyed not God as I ought, that I, also, might be vouchsafed these graces and glories. Woe is me, poor wretch!” After having thus viewed all the joys of the Just for the space of six days, the Angels lead the Soul again to do reverence to God. Therefore, the Church doth well, in that she celebrateth service and oblation for the Soul on the ninth day. After its second reverence to God, the Master of all commandeth that the Soul be conducted to Hell, and there shown the places of torment, the different divisions of Hell; and the divers torments of the ungodly, which cause the souls of sinners that find themselves therein to groan continually, and to gnash their teeth. Through these various places of torment, the Soul is borne during thirty days, trembling lest it also be condemned to imprisonment therein. On the fortieth day the Soul is again taken to do reverence to God: and then the judge determineth the fitting place of its incarceration, according to its deeds. Thus, the Church doth rightly in making mention, upon the fortieth day of the baptized dead.” [Hapgood, Isabel Florence. Service Book Of The Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic (Greco-Russian) Church. Houghton, Mifflin And Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1906): 612-613.]

[7] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn, Zeneida R-va.” (1885.) [Preparation of the text and comments by A.D. Tyurikov. Bahmut Roerich Center.

[8] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. My Childhood. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1893): 1-4.