PRINCE TYUMEN

July 1842.[1]

These were the times when simple highways were scares within the Russian Empire, let alone railways. A 2,000-mile journey was really difficult. Lelya, Vera, Leonid, Baba Lena, and Antonia, traveled in two large carriages, and, in case of foul weather, they also took a carrycot for their items and people. The sands were deep, so deep that the wheels of their heavy carriages sank up to the hub. The poor horses were no longer able to drag it, so at one of the stations huge camels relieved them of their burden. Once harnessed, they dragged the family along step by step, silently stepping with their wide, soft feet on the loose sand. The Kalmyk drivers, instead of sitting on the goats, ran along from the sides, or jumped onto the camels’ backs, driving them on with wild screams.

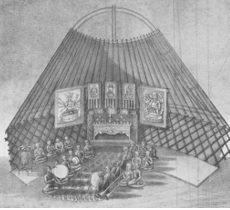

Interior of a khibitka temple. (1834). British Library.

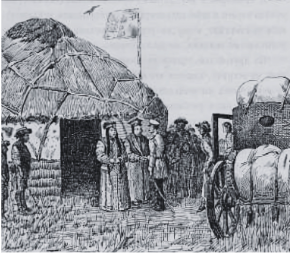

Lelya and Leonid looked out the carriage windows, amused by this amazing sight until it got dark, and they fell asleep, lulled by the silent swaying of the carriage over the eternal sandy mounds. The following day they were met by Prince Tyumen who asked that they stop and rest from the long, tiring journey, and stay as guests with his ulus, or tribe, where the nomadic pitched their tents in the summer months.

Before he was appointed governor of Saratov, Dede Andrusha lived in Astrakhan, where he ruled the nomadic Kalmyks and Kyrgyz. He was a kind and fair man, and therefore all his people retained a good memory of him and tried to serve him in any way they could. That is why the Kalmyk prince came out to meet them. They entered the ulus camp and stopped at a large, round, pointed tent with a wooden lattice frame, and a corium of felt. Meanwhile, crowds of Kalmyks in colorful robes and round fur hats encircled the carriage and greeted the visitors with obvious curiosity. Several smiling Kalmyks bowed low to the guests and joined the prince in escorting them inside the tent, which was upholstered and covered with carpets, mats, and silk fabrics.

Vera nearly gasped in surprise. A thin white tablecloth was spread out without a table, right on the floor, on top of the carpets. Instead of plates, there were deep colorful cups, and in front of each cup, there was a small colorful rug. Prince Tyumen sat the elders first on the few settings with pillows, while everyone else settled down as needed. Lelya sandwiched Vera between Antonia, while Aunt Nadya sat on the other side of Lelya whom she quickly engaged with in giggles and whispers. Vera pestered Antonia, as always, speaking to her in French. (Antonia had taught the girls so well, that Vera actually forgot how to address her in Russian!)

“Listen!” Vera whispered. “Why do these people have neither tables nor chairs? How can they live like this? Obviously they are rich! Look at the carpets, shawls, and silver they have! Why do they dine on the floor?”

“Not just on the floor, but just on the ground!” laughed Antonia. “There are no floors in these tents.”

“So much the worse! Aren’t they ashamed? Why don’t they build houses for—”

“I will tell you everything about them later,” said Antonia. “For now, just enjoy the excellent chicken soup that is being poured into the cups for all of us.”

Vera was about to follow her advice, raising the spoon to her mouth, but suddenly Lelya bent down and whispered in her ear.

“Don’t eat, Vera! This is horse broth! Kalmyks eat nothing but horses. Look! Look! There’s a horse’s eyeball floating in the soup!”

The spoon which Vera had raised to her mouth, involuntarily fell back into her colorful cup. She looked with disgust, first at the soup, then at Lelya, who was laughing and tugging at Aunt Nadya’s sleeve.

“It’s true, Kalmyks eat horse meat,” said Aunt Nadya, also laughing, “but don’t worry, they will not serve it to us.”

Then a tall Kalmyk brought a large silver jug, and began pouring some frothy, white, beverage into their glasses.

“This is mare’s milk, Vera,” Lelya again whispered.

Vera turned to Antonia for clarification.

“Yes,” sighed Antonia, “it is called kumiss.”

This was enough to instill in Vera a complete distrust of Kalmyk food.

After lunch, the men went with Prince Tyumen to see the Kalmyk the khurul (temple.) The Khoshutovsky Khurul, which Prince Tyumen had built, was a fairly recent structure, having been erected to celebrate the Russian victory over Napoleon. Women were not allowed there, so Baba Lena, Antonia, and the children remained in the tent with several Kalmyk women. The girls examined the clothing of the Kalmyk women, who were not at all embarrassed by the curiosity of their guests. They wore bright silks, and velvet and brocade hats trimmed with fur. As for jewelry, they had coins and all sorts of trinkets in their black hair, on their arms, and across their chests.

There were many interesting things in Prince Tyumen’s ceremonial tent. Without any pity for the calmness of Baba Lena, who laid down to rest, Vera demanded clarification. “What kind of people are Kalmyks?” “Why don’t they live in real houses?” “Why do they dine without tables and chairs, sitting on their haunches?” “Why do they wear pigtails and earrings in their ears, like women?” “Is a khorul an idol?” “Where is Dede Andrusha, and why can’t we go there?” Despite the protests of Antonia, who guarded her peace, Baba Lena, as usual, patiently explained everything, as knew the customs of the Kalmyks well. She told how the Kalmucks employed trumpets fashioned from the thigh and arm bones of their deceased rulers and high priests.[2]

Vera learned that their idols were called Burkhans, statues depicting their gods. The word burkhan itself was the Turkified name for Buddha, a name which, at that time, was still relatively obscure. Despite the prohibition from interactions with Tibet, the Kalmyks ordered these Burkhans from the monastic centers in the Himalayas where their Dalai Lama lived. After sanctifying them with prayers, the Dalai Lama sent them out to his fellow believers everywhere. The Kalmyks considered women—especially women not of their faith and tribe—to be unworthy of seeing the idols in all their glory during worship.

“It is considered quite an honor to see their enshrined Burkhans,” said Baba Lena. “Look, you see there, in that little red cabinet, there is such a god made of painted clay! Now it’s closed, but wait a minute, it’ll probably be opened soon, then you’ll see.”

“What god do they believe in?” asked Vera.

“God among all peoples is One!” said Baba Lena. “Kalmyks are immigrants from Asia; there, many peoples of the Mongolian tribe, all the Chinese, Japanese, residents of Korea and the island of Ceylon are Buddhists, and they venerate Buddha, their teacher, as a prophet, who lived much earlier than Jesus Christ was born on earth. He was a very intelligent and virtuous man and preached a very pure, moral teaching.”

“So why do Kalmyks worship some kind of clay dolls?” Vera interrupted.

“Very ugly dolls at that—with several arms, and blue, red, and gold faces!” laughed Lelya. “I remember the Burkhan figure from your office in Saratov.”

“Yes, but don’t think that they worship them alone,” Baba Lena explained. “Buddhists, like us, recognize the invisible, omnipotent God, the Creator and Creator of everything. They invented a very ugly appearance for their prophet, Buddha, just like their other fictitious gods. They pray to them by bowing to their images and bringing them gifts, just as we pray to icons.”

“Gifts? What gifts? Why do they need gifts?

“Patience, dear,” said Baba Lena. “When they serve us tea, you will see for yourself.”

While waiting, Baba Lena pointed out some kind of barrel reminiscent of a coffee mill next to the cabinet with their deity. It was painted with red paint and inscriptions from an unknown language.

“They have a wonderful prayer apparatus,” Baba Lena laughed. “Inside this barrel is a very long sheet of paper. On this paper, prayers are written and screwed onto a wooden rod to which this handle is attached. If you turn the handle to the right, the sheet unfolds, and if you turn it to the left, it rolls back onto the rolling pin. Saying prayers, or unfolding them, makes no difference to the Kalmyk! So, when they are too lazy to pray at a certain time or have no time, they will come up and turn the handle. They will unroll and turn the prayer sheet again, and they think that they have prayed!”

“Fools!” said Vera.

“And we have the very same fools!” Lelya cried out. “It does not it matter what they twirl in their hand. What is more ridiculous is muttering prayers under your breath while quarrelling with the maids, or slapping us on the back of the head, as our Baba Kapka does. Such a prayer is far worse than Kalmyk spinning!”

Everyone began to laugh.

At this time, the same tall Kalmyk who had previously served them kumiss now brought tea on a tray which he poured into glasses, and behind him came another, old, small, fat, like our old woman Kapka in Saratov, with a small tray on which there was some then drinking in small colorful cups.

“Look what he will do!” said Baba Lena, taking a glass of tea.

A little old Kalmyk man walked up to a dais covered with colorful silks, on which stood a small cabinet. The man produced some colored candles and lit them, and between them, he placed the cups he had brought while muttering his prayers under his breath. He then opened the two halves of the doors.

Inside the cabinet, there was a portly, almost naked figure, brightly painted. He was sitting crossed-legged, with its arms spread out on both sides.

“That’s what they think God looks like?” Vera involuntarily whispered.

“Don’t offend them!” said Baba Lena, reproaching her in French. “They all understand the Russian. Besides, this little guy isn’t that ugly. They have a main god—Shakyamuni they call him—he’s scary! They paint him surrounded by flames. In the khurul, candles are always lit in front of them, and offerings of flowers, wheat, oil, and water.”[3]

The figure Baba Lena described was not Shakyamuni at all, in fact. Rather it was a protector deity known as Mahakala. But perhaps this is the name they gave to their god, and Mahakala was a particularly important figure for the Mongols. Kalmyk traditions were, after all, something of a crossbreed, not unlike the Shamans of Siberia.[4] These stones were highly venerated among Lamaists and Buddhists, the throne and scepter of Buddha were ornamented with them, and the Dalai Lama wore one on his fourth finger of the right hand. They were found in the Altai Mountains and near river Yarkuh.

“But for what? Do they think that these idols drink and eat?”

“I don’t know. Maybe they do!” said Baba Lena. “They themselves never eat or drink anything without placing treats in front of the Burkhans.”

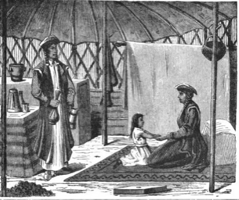

Kalmyk Women In A Tent.[5]

After finishing their tea, Baba Lena, Antonia, and the children went for a walk with the wives of the princes and Kalmyk nobles. They were draped in so much brocade, velvet, and gold and could hardly turn their heads from the weight of their hats and coins. One young woman, with almond eyes and thick black eyebrows, was particularly well dressed. Her underdress was fashioned from gold brocade, with red velvet flowers, and on top she wore a blue satin robe.

“So they dressed up like peacocks to please us!” said Lelya quietly. Their black calico dresses, dusty and wrinkled from travel, seemed even uglier when compared to the rich costumes of the noble Kalmyk women. “We must look like crazy people to them.”

“And yet all these ragamuffins,” said Aunt Nadya, pointing to the crowd that had poured out behind them, “are running, to look at us!”

“Or maybe they are looking at their princesses?” suggested Vera. “They are so magnificent!”

“They always see them!” objected Aunt Nadya. “But Russians rarely come to visit them.”

“Especially such Russian guests—important, like Dede Andrushka!”

They continued their walk through the nomadic camp, past the khurul where the Kalmyk priests were officiating some ceremony. There was such trumpeting, horns, bells, and drumming that they had to cover their ears so as not to go deaf.

“This must be their vesper service,” suggested Vera. “They’re making their Shakyamuni happy.”

The sun was already setting when Dede Andrushka arrived in a came-driven carriage to travel with them to Saratov for the remainder of the journey.[6] Before their departure, the venerable high priest, a Heloung of the Kalmuck tribe, gifted them a talisman. It was a simple carnelian stone known as an Ayu and naturally possessed (or had been endowed) with very mysterious properties. Engraved upon it was a triangle within which were written a few mystical words.[7]

-

- MOTHERS & DAUGHTERS

- A LANTERN

- CHRISTENING OF THE DOLL

- DASHA & DUNYA

- GRUNYA

- NANNY NASTYA

- NANNY’S FAIRYTALE

- CONFESSION

- IN THE MONASTERY

- PREPARATIONS FOR THE HOLIDAY

- EASTER

- THE DACHA

- THE MELON POND

- MIKHAIL IVANOVICH

- THE WARLIKE PARTRIDGE

- LEONID

- NEW WINTER

- HISTORY OF BELYANKA

- THEATRES AND BALLS

- YOLKA

- REASONING

- ROAD

- CAMP

- IN NEW PLACES

- THE GRAY MONK

- VARENIKI

- THE TRIP TO DIKANKA

- WHAT HAPPENED IN THE DOLL HOUSE

- ANTONIA’S STORY

- “A WINTER EVENING”

- THE BLACK SEA

- CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

- PANIKHIDA

- PRINCE TYUMEN

SOURCES:

[1] Fadeev writes: “Having buried our daughter, we had no reason to stay in Odessa for long, and we didn’t want to. (172) Moreover, from the news I received from Saratov, I learned that there were increasing squabbles and disorder because of the petty, demanding and restless nature of the vice-governor. We intended to go to Taganrog by steamer, but my wife could not stand the seasickness. In addition, we were afraid of difficulties with small children and grandchildren, which forced us to decide to split into two parties and go different ways: I, my son and daughter Ekaterina, would go by steamer, and Elena Pavlovna with her youngest daughter and small grandchildren would go there by land and having gathered in Taganrog, continue the journey together to Saratov. We left on July 10. Our journey on the steamer can be called successful, even pleasant. The company was good, the weather was favorable, the sea was calm, we admired the views of the southern coast of Crimea, so familiar to me for so long, to Yalta, where the steamer stopped for a few hours, and we took advantage of this time to take a short walk along the southern coast to Alupka. One of the passengers traveling with us, a Saratov landowner, Count Apraksin, who had a dacha in Yalta, offered us his horses and a carriage for our walk, which we accepted with gratitude, since it was difficult to find a carriage to hire there at that time, and there was not enough time left. Count Apraksin usually lived part of the summer and winter at his Yalta dacha.” [Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 171-172]

[2] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 600.

[3] [Mahakala was particularly important for Mongols at that time and signified the sovereignty.]

[4] Blavatsky writes: “What is now generally known of Shamanism is very little; and that has been perverted, like the rest of the non-Christian religions. It is called the ‘heathenism’ of Mongolia, and wholly without reason, for it is one of the oldest religions of India. It is spirit-worship, or belief in the immortality of the souls, and that the latter are still the same men they were on earth, though their bodies have lost their objective form, and man has exchanged his physical for a spiritual nature. In its present shape, it is an offshoot of primitive theurgy, and a practical blending of the visible with the invisible world. Whenever a denizen of earth desires to enter into communication with his invisible brethren, he has to assimilate himself to their nature, i.e., he meets these beings half-way, and, furnished by them with a supply of spiritual essence, endows them, in his turn, with a portion of his physical nature, thus enabling them sometimes to appear in a semi-objective form. It is a temporary exchange of natures, called theurgy. Shamans are called sorcerers, because they are said to evoke the ‘spirits’ of the dead for purposes of necromancy. The true Shamanism—striking features of which prevailed in India in the days of Megasthenes (300 B.C.)—can no more be judged by its degenerated scions among the Shamans of Siberia, than the religion of Gautama-Buddha can be interpreted by the fetishism of some of his followers in Siam and Burmah. It is in the chief lamaseries of Mongolia and Thibet that it has taken refuge; and there Shamanism, if so we must call it, is practiced to the utmost limits of intercourse allowed between man and ‘spirit.’ The religion of the lamas has faithfully preserved the primitive science of magic and produces as great feats now as it did in the days of Kublai-Khan and his barons. The ancient mystic formula of the King Srong-ch-Tsans-Gampo, the ‘Aum mani padme houm,’ effects its wonders now as well as in the seventh century. Avalokitesvara, highest of the three Boddhisattvas, and patron saint of Thibet, projects his shadow, full in the view of the faithful, at the lamasery of Dga-G’Dan, founded by him; and the luminous form of Son-Ka-pa, under the shape of a fiery cloudlet, that separates itself from the dancing beams of the sunlight, holds converse with a great congregation of lamas, numbering thousands; the voice descending from above, like the whisper of the breeze through foliage. Anon, say the Thibetans, the beautiful appearance vanishes in the shadows of the sacred trees in the park of the lamasery.” [Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 626-628.]

[5] Bettany, George Thomas. The World’s Inhabitants. Ward, Lock & Co. London, England. (1888): 429.

[6] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. My Childhood. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1893): 4-15.

[7] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 600.