ROAD

Spring 1841

With the approach of spring, Helena Andreevna began to say that it was time for them to get ready for the journey. She felt sorry for her husband, who missed his family dearly. Colonel Hahn wrote that his battery had been moved to a good place in Little Rossiya, where it is warm. He said it would be a good place for Helena Andreevna to live and begged her to return in the spring. Despite Baba Lena’s grief, and requests to wait until the summer, Helena Andreevna decided that she would leave in early spring.

Vera was very sorry to part with her family, and especially with her dear Baba Lena who could not look at them without tears. She cried a lot and locked herself in the study with Helena Andreevna and talked for hours. Vera still thought, with pleasure, about the upcoming journey. All children are hunters of change and love the road very much. They were occupied so much with the preparations of the trip, that Vera said goodbye to her friends without much grief and even stopped crying not long after parting with her family, who saw them off far out of town that June.[1]

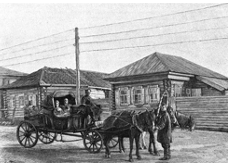

Tarantas.

Their caravan consisted of two carriages and a tarantass. In one carriage sat Helena Andreevna, Antonia, and Vera; in the other sat the maid Annushka with Leonid in her arms, and the doctor, who accompanied Helena Andreevna at the request of Dede Andrushka. Later the maid Masha took the doctor’s seat when he transferred into the tarantass to join Miss Jeffers who, owing to a headache, insisted that she could not travel in a closed carriage.

Lelya traveled all the way alternating between both carriages and the tarantass, for she could not sit in one place for very long. At almost every station the most unexpected incidents happened to her. She was such a lively minx that the governess had quite a lot of trouble with her. At one station, on the porch, a passing officer sat in an unbuttoned frock coat and a hat on the back of his head. He looked at everything from under his brows with dull eyes, either sleepily or angry, and, puffing loudly, smoked from a long chibouk. Helena Andreevna told the girls not to approach him, and Vera happily stayed away (she was afraid of his ferocious appearance.) Lelya, however, constantly walked past him, turned around, and glanced at him, trying to attract his attention and talk to him. (She really loved talking to strangers. The gruff traveler paid no heed to her, he simply groaned and smoked his pipe.

“Look, Verochka!” Lelya said with a smile, “It’s exactly the same kind of pipe as Papochka’s! Do you remember?”

Vera did not remember this at all and, looking reproachfully at Lelya, moved even further away.

Lelya, jumping up, bravely turned to the officer. “What a long pipe you have!” she said.

The man slowly raised his red, swollen eyes to her, but did not say a word.

“Our Papochka has one too,” she continued briskly, taking another step towards him.

“What is all this now…your what?” the officer muttered hoarsely.

Lelya moved away a little, but, continuing to look at him cheerfully and fervently, explained. “Our father smokes exactly the same pipes as you—with long stems.”

“What?!” the officer roared in such a deep bass voice that Vera jumped back to the door in fright.

“Long pipes?.. And… why do you have such a short nose? Huh?!” he said, suddenly rising.

Here Lelya was confused and, taking a few steps back, looked at the officer in bewilderment.

The man suddenly sank back into his seat, stretched his legs across the floor, threw his head back, and instead of a bass voice spoke in a thin voice. “Such a little girl! Why are you fidgeting?!”

This exclamation struck Lelya like thunder! She felt even more offended and annoyed by Annushka’s laughter, who heard everything from the carriage where she was sitting next to sleeping Leonid.

“You see!” said Vera, following Lelya into the room where Miss Jeffers called them. “Why were you really fidgeting?”

“None of your business!” said Lelya, even more angry. (After this incident, she stopped talking to strangers.)

In the last city, they found the horses sent for them and rode on their own. Having learned about this, Vera waited every minute for them to arrive and see their father whom she vaguely remembered. It turned out, however, that they were driving and could not get there! The road went through green fields, past pretty oak groves and farmsteads closed with gardens. Birds were singing, butterflies were fluttering in the greenery. There were so many flowers along the road that one could have run to pick them in the fields and groves! But they were in a stuffy carriage, swaying from side to side.

“Where is the city?” Vera asked.

“What city?” Helena Andreevna replied.

“The city where Papa lives, where we are going to live!” Vera explained.

“There is no city there. We will live in the village.”

“In the village!?” Vera was surprised. “Whose village?”

“It’s no one’s village—or rather, it’s the sovereign’s village,” said Helena Andreevna. “Don’t you remember how we used to live in villages? Where they put Papa’s Battery— that’s where we will live.”

“Yes! I remember. Where the soldiers, and officers, and guns are.”

“I’m sure that you are impatient to see Dad,” said Antonia, speaking to Vera, as always, in French. “Don’t bother your mother,” she added quietly, “talk to me.”

“Yes,” Vera answered hesitantly. “I want to see him, but…I don’t remember well! Is he as red-haired as Lida’s brother?”

“Why do you say that?” Antonia laughed.

“Because, I remember he had a red mustache, and he always pricked me when he kissed me.”

“So, all you remember is his red, spiky mustache?” said Helena Andreevna laughing, pinching Vera on the cheek. “Do you remember how you taught your old nanny Orina to dance in Gadich?”

“Oh, yes, nanny Orina!” remembered Vera. “And she’s here too, mamochka?”

“No, baby, she stayed there, in her village.”

“Ah! What a pity! Why?”

“She doesn’t want to come to you,” the doctor intervened, chuckling. “She says that you pinched and beat her hard when you taught her to dance. She’s afraid that you’ll sign her up as a dancer again.”

“Oh, stop it, please,” said Vera with annoyance. She really could not stand this nasty doctor! (It was the same doctor whom Nanny Nastya said had “sideburns like a dog.” Besides, he made her cry recently by knocking out a loose tooth with a snap.

They had been climbing the mountain for a long time, stopping often to let the tired horses rest. No matter how hard their soldier-coachman tried, no matter how much he waved the reins and hung from the high box, no matter how much their cook Aksentiy whistled, shouted, and fussed with a whip in his hands, the matter ended with the horses becoming stale.

“I asked for six, but no! Four horses!” the coachman grumbled.

“What should we do now?” said Helena Andreevna with worry. “Can’t I change to a tarantas to get there faster?”

The doctor would not allow this, saying that shaking was very harmful to Helena Andreevna. They decided to send Aksentiy on horseback for help, and although their lazy cook made the excuse that he didn’t know the road, the coachman shamed him:

“Just let the horse go, lad. It will take you straight to the battery stables! It’s just a stone’s throw

away! The mountain is only inaccessible here,” he added, “but as soon as we get out, the camps will be right there.

“Nothing to it!” said Aksentiy. He climbed onto the horse’s back, and galloped off, jumping high. His flowing grey overcoat and flapping elbows were a comical sight. Their coachman calmly lit a short pipe, and everyone except Helena Andreevna (who was lying with her eyes closed, trying to fall asleep,) got out of the carriage and scattered around. With a gingerbread in her hands, Vera sat down nearby on the boundary, admiring the many larks that scurried around in the fields. They flew out of the grass, rustling their wings; soared like arrows, and disappeared into the heights, from where thousands of their silvery songs were heard. They would then descend quickly, and directly, to the ground, flash their perky little tufts, waddle among the crops, and disappear again, plunging into the grass.

The horses sighed. Perhaps it would be better to take them out now.

“What about the tarantas?” asked Antonia, who was sitting on a large stone by the road, amusing Leonid.

“The tarantas is light!” said the coachman. “It is better than just standing around and waiting.”[2]

-

- MOTHERS & DAUGHTERS

- A LANTERN

- CHRISTENING OF THE DOLL

- DASHA & DUNYA

- GRUNYA

- NANNY NASTYA

- NANNY’S FAIRYTALE

- CONFESSION

- IN THE MONASTERY

- PREPARATIONS FOR THE HOLIDAY

- EASTER

- THE DACHA

- THE MELON POND

- MIKHAIL IVANOVICH

- THE WARLIKE PARTRIDGE

- LEONID

- NEW WINTER

- HISTORY OF BELYANKA

- THEATRES AND BALLS

- YOLKA

- REASONING

- ROAD

- CAMP

- IN NEW PLACES

- THE GRAY MONK

- VARENIKI

- THE TRIP TO DIKANKA

- WHAT HAPPENED IN THE DOLL HOUSE

- ANTONIA’S STORY

- “A WINTER EVENING”

- THE BLACK SEA

- CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

- PANIKHIDA

- PRINCE TYUMEN

SOURCES:

[1] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 167.

[2] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. How I Was Little. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 170-177.