THE TRIP TO DIKANKA

September 1841

Time passed so quickly between studies and pranks that the girls did not even notice that the end of summer had arrived. The oak groves were full of color, the mountain ash and viburnum were turning red, and the pears and apples in the orchards had already been harvested. The Autumn of 1841 was heavenly. Though cold, the bright sun cheerfully illumined the groves and clean-shaven fields where long threads of shiny cobwebs flew. Vera loved catching this web, which they called “the Virgin’s hair,” and wrapped it around her hand as she ran, watching it spread out through the air behind her, shimmering silver in the sun. Then the gray, stormy days came, whipping the yellow leaves up into the unsightly sky. The quails and pigeons stopped crowing and cooing. They frowned, ruffled their feathers, and more often hid in the houses set up for them in the yard.

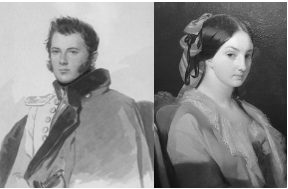

(Left) Lev Victorovich Kochubey (Right) Elizaveta Vasilievna Kochubey.

Helena Andreevna was permitted by Princess Elizaveta Vasilievna Kochubey (who was then abroad) to borrow books and sheet music from the library of her estate in Dikanka. Whenever she returned, she brought with her wonderful flowers, books, and music, and told the girls about many interesting things. Naturally, the girls really wanted to visit, too, and on a clear September day, their wish came true.

The ancestral home of the Kochubey family, descendants of Cossack officers that possessed large land estates in Little Russia. As the girls walked with Helena Andreevna through the grounds, they were awestruck by its opulence. The property was improved by Elizaveta Vasilievna’s father, the late Prince Victor Pavlovich Kochubey, and its beauty was said to rival the Borgia villas of Rome.[1] There was a park and a greenhouse with flowers, the likes of which the girls had never seen. In front of a wide porch that was decorated with vases and climbing greenery, there was a colorful flower garden, laid out like a carpet in a Turkish pattern. From the middle of the flower garden, a fountain gushed high, falling in a cloud of foam and splashed into the white marble pool. Inside, there were galleries with marble columns, floors made of colored patterns, and magnificent halls decorated with paintings, statues, and mirrors.

Their escort was a handsome white-haired old footman who wore a white cravat and a black tailcoat. He walked with them everywhere and showed them everything. While Helena Andreevna was busy with the books in the princess’s library, putting back the ones she had read and choosing new ones, Vera stood on the terrace, admiring the flowers and the fountain. She finally entered the hall, where she was occupied by a shiny parquet floor that reflected her white dress and legs like a mirror. Having passed through several large, beautiful rooms, she entered the princess’s small corner office, entirely upholstered in something blue and soft, like the upholstery inside of expensive bonbonnieres.

A large glass door, which took up almost an entire wall, was open to the garden.

At a distance, standing near another door, the old footman invited Helena Andreevna to look at the princess’s own drawing in an album. Helena Andreevna and Antonia examined the book placed before them on a desk. Both of them smiled strangely, Helena Andreevna did not expect this at all, and studied the pictures with warm curiosity and pleasure.

Helena Andreevna’s satisfied face immediately attracted the girls’s attention, and Lelya and Vera (standing on tiptoes) went to look, too.

“The princess drew this herself? asked Helena Andreevna, looking cheerfully at the old man.

“In your little book, madam,” said the footman, respectfully. “Based on this drawing, her ladyship also deigned to paint a picture, a little more detailed, with oil paints—but that one she took with her to foreign lands.

“Does the princess paint a lot?”

“Whatever she reads or thinks of her ladyship sketches with a pencil, and then goes upstairs to the studio. She will take a palette and brushes and paint with oils, sometimes for hours at a time.”

“May I see this workshop?”

“Why, madam, her ladyship instructed me to show you everything. Whatever you please! Books, paintings, flowers.”

This was quite the honor. Typically, guests had very limited access to anything at the estate, perhaps a tour of the gardens, greenhouse, or some rooms in the mansion.

“Her ladyship really likes your books, madam!” the footman continued. “Did you deign to see in the library how richly bound her ladyship’s excellency’s works are? It happens that when a new work of yours comes out, all they will talk about is ‘Zenaida R-va.’ They remove the stories you write in the magazines and order them to be bound with wonderful binding. Why, sometimes at dinner or in the evening with guests, even we servants hear everything about you, and the talks about your writings. So, I, the old man, became curious. I got a magazine from the manager and read this very “Theophania Abbiaggio” which inspired her ladyship to make this picture.

“Qu’est ce qu’il dit?” whispered Vera to Antonia in great bewilderment, but she was so busy listening to the old man’s story that she didn’t seem to notice.[2]

Helena Andreevna quietly placed the open album on the table, and Vera glared at it. There was a picture of a woman standing on a high rock, wearing all white with black hair flowing over her shoulders. Below, under the rock, there was a dark sea, and its waves, and the dress, and the woman’s long hair seemed to be lifted and scattered by the wind.

“Let’s go, Verochka,” said Antonia, “it’s time to go home!” Taking the album from Vera’s hands, she closed it and walked out of the room, following Helena Andreevna while quietly talking to her.

The old footman followed them. In the hall, he took a magnificent bouquet out of the water and gave it to Helena Andreevna.

“This was specially prepared for you,” he said, escorting them to the porch “Would you like to take a basket of duchess and apples-reinettes with you, madam? I must admit, I was planning to send them to you all week, but the manager was leaving for the fair, and he took almost all the horses.”

Helena Andreevna thanked the polite old man, and they left.

Though very curious, it was only the following evening that Vera managed to ask Antonia about the drawing of the woman.

They were sitting on the porch of the house, having just finished their lessons. The sun was setting, but dark clouds had crawled out across the sky. Here and there nearby houses with gardens glowed with bright spots against the blue background of the distance. Antonia was sitting with her work and invited Vera to play in the yard. Vera, sitting down at her feet, admired the bright rays of the sun, spreading across the sky like arrows that pierced the dark clouds.

“The weather will turn bad. It’s the end of clear days!” said Antonia, looking in the same direction. “Look how beautiful the clouds are—like waves on the sea.”

“Ah!” said Vera. “I wanted to ask you—what kind of picture were you looking at yesterday in Dikanka? Who was this woman on the rock by the sea? What did this old man tell you?”

“What did he say?” said Antonia. “Well, you know that your mother writes in her room almost every day for several hours?”

“Yes, I know. Well?”

“Well, what she writes is taken from her and published in books. These books are her compositions.

She writes nice things that everyone likes. Everyone reads them, and so this princess, the owner of Dikanka, read one of her works and drew a picture for it.”

“For mamochka’s book?”

“Yes. Not for the whole book, but for one place in it that she liked.”

“What kind of woman is this with her hair down?

“The one your mother wrote about in her story. Her name is ‘Theophania Abbiaggio.’”

“Did Mamochka know her?” Vera interrupted.

“No, your mother couldn’t know her, because she never really existed in the world. She made up her story.”

“How could she? How did she know? And who will believe her? After all, everyone can find out that she lied!”

“She didn’t lie,” Antonia corrected, smiling, “but she made it up.” This is a difference that you still cannot understand. Everyone knows that she does not write about real living people, but she talks about them so well, describes them so accurately and vividly that when her books are read, everyone gets lost in another world.”

Vera thought deeply and after a minute asked: “Well, how could the princess paint a portrait of Theophany—”

“—Theophania.”

“How could the princess paint Theophania if she hasn’t seen her?”

“Of course, she hasn’t seen her; but she imagined her from your mother’s story.”

“What if Mamochka says that she didn’t draw her properly…that she doesn’t look like that?”

“Mama won’t say that!” Antonia laughed. “She is drawn the way mom described her in the book.”

“Can I read this book?”

“No, now you can’t, because you won’t understand anything about it; but when you grow up, you will certainly read everything that your mother writes.”

“Ah! How does she write this? How I wish I could do it too! Who publishes her works?”

“They are printed in St. Petersburg. Have you seen the large yellow and green books that they bring to us from the post office? They are called magazines. They publish the works of different people and pay them money for it.”

“Mamochka gets paid money too?!”

“Yes.”

“Who pays her?”

Antonia, as clearly as she could, explained the magazine business to Vera and added that in payment for her writing, Helena Andreevna paid the salary of Miss Jeffers, the teachers, and purchased the books and material for the children’s education.

“Does she pay you too?” Vera asked.

“No,” Antonia answered, blushing, “she doesn’t pay me anything. I receive money from the Tsar, and I live with you because I don’t love anyone in the world as much as your mother.”

“What about your relatives?”

“I have no relatives.”

“How? Is there really no one? No father, nor mother, nor brothers, nor grandmother?”

“Absolutely no one,” said Antonia. “Well, I do have one brother, whom I don’t know at all.”

“How can you not know your brother?”

Antonia remained silent, and Vera’s mind jumped to another question.

“Why does the Tsar pay you money?” asked Vara. “Does he really know you?”

“What a funny girl you are!” she laughed again. “You need to know everything!.. Well, the Tsar pays me money for the fact that I studied well.”

“Because you studied well? That’s it! If I study well, will he pay me too?”

“I Don’t know! Maybe he will, but first things first, you need to start studying very well! Now, that’s enough questions for now. It’s really dark now. Soon we’ll light candles and tea will be served. Let’s go to the room.”

Antonia left, but Vera did not follow her. Putting her elbows on her knees and resting her head on her hands, Vera looked into the darkening distance and thought deeply about her kind mother who worked for them. She thought about how smart she was, how she could talk so well about unprecedented people and things that even princesses believed her and thought that she was telling the truth! Before then, she had never thought about what she was doing in her office. Now these activities acquired a special meaning and interest for her. It was as if her mother had become someone else—not just her mother like before, but also someone new, someone different! She began to study her mother’s pale face.[3]

“Why is Mamochka smiling so strangely?” she thought. “Not like how others smile. Her smile is sad. What eyes she has—big and dark, yet, bright and shiny at the same time. My mamochka is very pretty, and I love her terribly!”

“What is wrong with you?” Helena Andreevna would laughingly ask, catching Vera’s gaze. “Why do you look at me like this?”

Vera, embarrassed, did not know what to answer, but she watched her more and more, and for the first time her mother’s health began to worry her. Helena Andreevna jokingly nicknamed Vera her “watchwoman.”

Helena Andreevna continued sitting at her desk for hours, writing new stories. Vera would sneak quietly into the room and nestle somewhere in a corner unnoticed by Helena Andreevna, Peering at her mother from behind some papers, she tried to figure out how she wrote so well that people paid her money for it. “What is she writing about now?” she thought. Vera was mesmerized by how quickly her mother’s small, white hand flew across the paper. She was fascinated by how her mother would stop, re-read some sheets, and get lost in thought. Absentmindedly fixing her eyes on some spot in the room, sometimes Helena Andreevna would smile as if seeing something in front of her, and sometimes she frowned her thin eyebrows, and her face would become so serious and sad. Then her mother would again take up the quill and write intently and quickly without stopping.

New thoughts began to come into Vera’s head and began to relate to everything around me differently. She thought more often, tried to look into everything, and listen more attentively to the conversations of the grownups. She was especially interested in Antonia’s long conversations with her mother, when they, sitting on a soft sofa in the evening, alternately read and talked about things that were often completely incomprehensible to her, but which she tried to understand (or supplement the incomprehensible with her imagination.) She no longer pestered Antonia as often as before with questions about trifles. In several instances, however, the questions Vera did ask were confusing to Antonia. Two or three times it even happened that Antonia could not, or did not want to, answer and gave a general reply that Vera would “learn about all this when you grow up.”

“When will that be?” Vera pressed. “When will I finally grow up to talk and read about everything and understand everything? When will I finally be big?!”

Vera sincerely thought at that time that this would never happen.[4]

-

- MOTHERS & DAUGHTERS

- A LANTERN

- CHRISTENING OF THE DOLL

- DASHA & DUNYA

- GRUNYA

- NANNY NASTYA

- NANNY’S FAIRYTALE

- CONFESSION

- IN THE MONASTERY

- PREPARATIONS FOR THE HOLIDAY

- EASTER

- THE DACHA

- THE MELON POND

- MIKHAIL IVANOVICH

- THE WARLIKE PARTRIDGE

- LEONID

- NEW WINTER

- HISTORY OF BELYANKA

- THEATRES AND BALLS

- YOLKA

- REASONING

- ROAD

- CAMP

- IN NEW PLACES

- THE GRAY MONK

- VARENIKI

- THE TRIP TO DIKANKA

- WHAT HAPPENED IN THE DOLL HOUSE

- ANTONIA’S STORY

- “A WINTER EVENING”

- THE BLACK SEA

- CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

- PANIKHIDA

- PRINCE TYUMEN

SOURCES:

[1] Bashkirtseff, Marie. (trs.) Hall, A. D.; Heckel, G. B. The Journal Of Marie Bashkirtseff: Vol. I. Rand, McNally & Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1890): 276.

[2] [Fr. “What did he say?”]

[3] Helena Andreevna felt severe weakness and developed inflammation in her side. She constantly had to resort to eyes patches and mustard plasters. In November 1841 she wrote to her relatives: “When I sit for five hours, I feel pain in my chest or a tingling in my side. I’m so weak that I can’t stand or walk alone, my legs give way, and sometimes it’s very hard on my chest.” [Nekrasova, E. S. “Helena Andreevna Hahn (1814-1842): Part II.” Russkaia Starina. Vol. LI, No. 9 (September 1886): 553-574.]

[4] Zhelikhovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Helena Andreyevna Hahn (1835-1842.)” Russkaia Starina. Vol. LII, No. 3 (March 1887): 733-766; [Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. How I Was Little. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 203-208] & [Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. How I Was Little. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 209-215.]