Oz: A Story Of Ancient Initiation

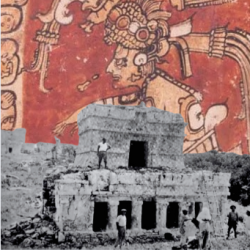

On February 16, 1906, my great-great Grandfather, Domenico Tarallo, left Naples, Italy, on board the Prinzess Irene, arriving in New York on February 28 to begin his new life in America.[1] It was when researching what that journey would have looked like that I learned of a (small) family connection with the author of The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz. It seems that L. Frank Baum and his wife, Maud Gage Baum, took their first and only trip abroad in early 1906, sailing out of New York on January 27 aboard the Prinzess Irene, and changing ships in Naples before continuing to Egypt.[2] Maybe Domenico saw them in port.

When Domenico disembarked from the steamer in Manhattan in late February the journalist Upton Sinclair had just released his exposé, The Jungle.[3] It was about an immigrant’s experience in the slaughterhouses of Chicago, the city where Domenico proceeded from New York. It was a time of “muck-raker” journalists and social activism. A week or so before his arrival, Charlotte Teller announced the creation of the “A Club,” a Bohemian collective that met in her home at 3 Fifth Avenue. Within a year she would publish her own work, “The Cage.” Like The Jungle, the work took place in Chicago and explored the experience of the emigrant. It had an unapologetically Socialist slant, being a romance that took place during the Haymarket Massacre of 1886.[4]

If an ecosystem is a community of living organisms that interact with one another and their physical environment, perhaps there is a noetic counterpart. Since “eco” means “home,” perhaps we might call it an “ectosytem,” (“ecto” meaning “outside.”) The realm of ideas that interact with one another and interface with their (sometimes) physical environment. Take the “ectosystem” of thought in 1848 for example. In nearly every nation across Europe (and to some extent the Americas,) the Revolutions of 1848 emerged to challenge the existing order. It was around this time when John L. O’Sullivan of the “Young America Movement” coined the phrase “Manifest Destiny” in reference to the annexation of Texas.[5] It was the year that the Fox sisters first heard the spirit-rappings in Hydesville, New York.[6] In Europe, it was the last and greatest of the middle-class revolutions which convulsed periodically since 1789. Galvanized by an optimistic faith in human capacity for self-government, the revolutions released a torrent of energy that overwhelmed the existing conservative political order. It was the “springtime of nations,” when barricades were erected in the capitals of Europe. Angry mobs vandalized royal palaces; unpopular ministers resigned and went hurrying into exile; and exiled revolutionaries hurried home as heroes. To liberals, it seemed as though a new world was being born, and a new era of liberty, justice, and religious freedom had begun.[7] 1848 was the beginning of the first Italian War of Independence. “Italy” at the time was a collection of kingdoms predominantly under the yolk of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It began when the population of Milan rebelled against their Austrian garrison, and quickly found support among the revolutionaries of the “Young Italy Movement,” like Giuseppe Mazzini, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, two champions of Italian unification.[8] It swept across the German kingdoms, and it was in this political atmosphere that Karl Marx broke ties with some of Hegel’s major theories, inverting idealism into materialism and questioning the Hegelian conception of state in his Communist Manifesto.[9] Another result of the Revolution of 1848 was the Basic Rights of the Frankfurt Parliament which declared that civil rights were not conditional on religious belief. Little surprise that Spiritualism, Socialism, Free Love, Free Thought, Liberalism, etc., have, since their inception, been lumped together.

In 1857, a more mystical strand of Spiritualism developed in France under Hippolyte Rivail (who wrote The Spirits Book in 1857 under his more popular name, Allan Kardec.)[10] It became customary to differentiate between Spiritualism and French Spiritism, the latter including a cosmology that put forth the novel concept of reincarnation. Though it shared fundamental elements with its American progenitor, Spiritism differed on key doctrinal points that made it more attractive to believers from Catholic and Eastern Orthodox backgrounds.[11] That same year a student named Frederick L.H. Willis was expelled from Harvard Divinity School for acting as a Spirit-Medium.[12] The following year, Felice Orsini, an Italian refugee in France, nearly assassinated Napoleon III. Orsini came to believe that Napoleon III was the greatest obstacle to the success of revolutionary movements throughout Europe, so he went to Paris under a false name and resolved to assassinate the emperor.

When Orsini was killed, he became a household name; not just in Europe, but in America as well. In the spring and early summer of 1858, the citizens of New York, Boston, Cincinnati, and Chicago took to the streets, articulating with physicality what their words could not express, and trying to define what Orsini’s actions meant for American society, and the Atlantic world more broadly. Native-born democrats, and radical immigrants, found common ground in what they believed was Orsini’s strike for universal liberty. They faced off against liberal and conservative commentators, who denounced Orsini as a criminal and murderer. One thing was clear, Orsini’s death was a galvanizing moment for a broad interethnic, interracial, and cosmopolitan coalition. It was a catalyst that saw the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison move from non-resistance to more dynamic measures. “I am not only an abolitionist for the chattelized slave,” said Garrison, “but an emancipationist for the whole human race.”[13] It was probably no coincidence that the most famous of the “epidemic of apparitions,” the appearance of the Virgin Mary at Lourdes, occurred immediately after the failed assassination attempt.[14] In the summer of 1858 one of the most peculiar conventions took place in Rutland, Vermont. Writing to William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist, Parker Pillsbury, described it as one of the most “Reformatory Conventions ever held in this or any other country.” The topics most prominently considered, Pillsbury said, were “Spiritualism, the Cause of Woman, including Marriage and Maternity, Scripture and Church Authority, and Slavery,” and “the subjects of Free Trade, of Education, Labor and Land Reform, Temperance, Physiology and Phrenology were introduced, and more or less considered.”[15]It was quite a sight for rural New Englanders. “The curious people whom you are in the habit of meeting daily in New York are regarded with unmitigated wonder by the quiet Vermonters,” The New York Times stated. “Andrew Jackson Davis, with his queer hat and prophetic air, attracts much notice.”[16] (Davis being the father of American Spiritualism, who introduced the concept of the “Laws of Attraction” to the world.)[17] “The Woman’s Rights women are here in strong force,” the paper continued, dividing the honors with the Free-lovers. They were led by “prominent females” like Matilda Joslyn Gage, the mother of Maud Gage Baum and mother-in-law of Lyman F. Baum.[18] All three of them would join the Theosophical Society.

Founded in New York City in 1875, by Helena Blavatsky, Col. Henry Steel Olcott, and William Quan Judge, the Theosophical Society lost momentum in America in 1879 when its headquarters relocated to India. Of the three founders, only Judge remained in America to slowly build up the Theosophical Movement. Properly speaking, the Rochester Branch was the second Branch to be formed in New York, having been organized in July 1882 by Albert Leighton Rawson (1829-1902.)[19] William B. Shelley was named President, and the philanthropist-Spiritualist, Josephine Cables (1843-1917,) was named Secretary.[20] Having more members than Judge’s Aryan Branch in New York City, it was, for a time, regarded as “the elder brother in America.”[21] According to Judge, the Rochester Branch had many members of the “Liberal League,” prevalent in New York’s “Burned-over District” and New England.[22] Judge described them as “crackbrained spiritualists and free-lovers.”[23] In 1884 Cables established the occult journal, The Occult Word.[24] Around the same time, Olcott instituted a system of central management for the American Branches of the Theosophical Society, known as the American Board of Control. Olcott consulted with Judge, who provided names for leadership positions. Cables, now President of the Rochester Branch, was named Secretary.[25] It was decided that any new Theosophical Branches wishing formal recognition had to apply for a customary provisional charter issued by the American Board of Control.[26] By 1885, when Matilda Joslyn Gage joined the Rochester Branch, it was already filled with influential people.[27] Maud Gage Baum and Lyman F. Baum joined the Society in Chicago, in 1892, under the tutelage of W.P. Phelon.[28]

The Chicago Branch was chartered on November 27, 1884, by Stanley B. Sexton (President) William P. Phelon (Corresponding Secretary,) Mira Morse Phelon (wife of William Phelon and niece of Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph,) and newly-arrived immigrant, Jakob Bonggren.[29] Maud L. Brainard was named Secretary.[30] Other notable members of the Branch were: Rev. William H. Hoisington, and his wife, Lauretta Hoisington. Known as the “Blind Man Eloquent,” Hoisington, a famed lecturer on Egyptian history, joined the Society in 1876.[31] He was a “deep thinker and a man of scholarly attainments,” but was born with “defective eyesight” and became totally blind in adulthood. In 1880, he married Lauretta Cutter, head of the Female Department of the City Hospital of Cleveland. An active abolitionist, Lauretta was personally acquainted with John Brown and his family. Lauretta joined the Society in 1885. She was a devoted member and equally devoted wife; she read Theosophical literature to her husband for the remainder of his years.[32]

There was Antoinette V. Wakeman, a journalist on the staff of The Chicago Evening Post.[33] Mercie M. Thirds, another journalist from Chicago, was a talented writer, and poet, with a talent for Theosophical lecturing. Her talks were not limited to Illinois, as her discourses took her often to California (and a season in Hawaii.)[34] Gertrude Piper, though not a writer, was another woman who joined the Chicago Branch. She would later relocate to San Francisco where she was the Secretary of the local Branch.[35] Anna Byford Leonard, the first woman Sanitary Inspector of Chicago (and the United States) was an ardent Theosophist who joined the Society in late April 1886.[36] Two weeks after Anna Byford Leonard joined the Theosophical Society, a bomb planted by Socialist activists exploded at a labor demonstration in Haymarket Square, Chicago. This fatal riot, the Haymarket Massacre, was backdrop of Charlotte Teller’s The Cage.[37]

The Chicago Branch was small and poor, so, without the ability to rent a space, were compelled to meet in Leonard’s dining-room. What the Branch lacked in size; it made up for in devotion. Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled had replaced the Bible in many houses. One man made a practice of reading from it to his family every evening, and Sunday afternoons, and even questioned his daughter on the week’s reading as though it were a Bible lesson.[38] In late 1887 W.P. Phelon organized the “Ramayana T.S.” in Chicago, Illinois. Its roster was comprised of members with “considerable experience in ‘Spiritualism.’”[39] The Theosophists had their headquarters on the North side, while “the hot-bed of Spiritualism [was] on the West side.”[40]

“There is little doubt that the influence of Blavatsky […] is making itself far more widely felt than many people imagine,” one paper at the time remarked. Popular literature was “doing more to arouse public interest than any purely technical book on the subject is capable of accomplishing.”[41] Indeed, the world of popular fiction was where Theosophical teachings truly gained a footing. “There is growing every day among contemporary writers a strong disposition to take up theosophic doctrine,” W.Q. Judge stated. “This will grow as time goes on, for everyone with any means of judging knows that the doctrines of Karma and Reincarnation are gaining a hold, slowly perhaps, but surely, on the public mind. Both of these offer a wide field for novelists and magazine writers.”[42] Laura C. Holloway echoed the sentiments of Blavatsky and Judge regarding the Theosophical influence on popular media in an article for the Brooklyn Times-Union: “The most careless of observers must have noticed in the past four years the growing tendency in modern literature to discuss mysticism, occultism, and theosophy.”[43] She listed for examples Marion Crawford’s Mr. Isaacs, Marie Corelli’s The Romance of Two Worlds, and Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, and She. Other corners of the secular press took note as well. “There is little doubt that the influence of Blavatsky […] is making itself far more widely felt than many people imagine,” one British paper remarked. Popular literature was “doing more to arouse public interest than any purely technical book on the subject is capable of accomplishing.”[44] In California, one San Francisco paper stated: “The bookstores are full of feeble-witted volumes on Theosophy, telepathy, reincarnation, and esoteric Buddhism. Even the fashionable novelists have caught the fever.”[45] Of the literary sensations that echoed Theosophical themes, Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novel, Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, proved a useful tool for Blavatsky’s teachings. In this story Dr. Henry Jekyll develops an elixir that allows him to access his villainous, primal alter-ego, Edward Hyde. While initially able to control the altered-self, Dr. Jekyll eventually succumbs to Hyde.[46] Blavatsky offered her comments in an article “The Signs Of The Times,” in the second issue of Lucifer. “Literature—especially in countries free from government censorship—is the public heart and pulse,” wrote Blavatsky. “Besides the glaring fact that were there no demand there would be no supply, current literature is produced only to please, and is therefore evidently the mirror which faithfully reflects the state of the public mind.”[47] In her opinion, there was no grander psychological essay on occult lines existed than Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”[48] For her it was an allegory for the extremities of the spectrum of the human soul, from our “animal” part to our “Higher Self.”[49] This was known as the septenary (“seven-fold” conception of personhood. Something like a Russian nesting-doll, that is, a single “doll” comprised in layers. The smallest four dolls being the soul’s lower “animalistic” parts, or the “Hyde.” The largest three “dolls” would be the trinitarian aspect of our “High Selves,” or our “Christos.”[50]

Chicago’s own W. P. Phelon would write his own “occult novel” at the time, Three Sevens, A Story Of Ancient Initiations (1889.) “The crime and bloodguilt of a selfish world has oozed for ages, until the only hope of purification can be by fire,” Phelon writes. “Under Karmic law, [uncleansed vileness] piles up like the thunderheads upon the horizon, until a moral cyclone, or a mental thunderstorm restores equilibrium and the light of the Good, by manifestation, brings back the lost harmony.[51] In Phelon’s A Witch Of The Nineteenth Century (1893,) he writes:

The class consisted of four young ladies, all impressible on the psychic plane. None were more sensitive than Elsie, but while all seemed to possess this gift, there was a difference in the manifestation as well as in the capability for induction which each manifested. But Elsie, besides her unusual powers exercised at will, seemed pervaded with an indescribable dominant force that made itself felt as soon as any attempt at willpower was projected toward her by another. It was not exactly resentful or antagonistic, but a mixture in which any selfishness was left out and overcome by the influence of the mighty self-poise of the spirit itself.

But whatever might be the relative powers of these spirits, they were all united in one purpose and thought, and that purpose was the seeking of knowledge—a knowledge that might become wisdom when fully comprehended and assimilated.

Study on abstruse and occult lines was succeeded by experiments, first on the plainest and simplest lessons of introversion, passing from easy examples by almost insensible gradation to the higher and more difficult; commencing with the effects of thought upon one’s self and then upon companions, until standing on the threshold of the great gate of the temple of the Universe, they essayed to lay hold of the mighty powers whose mastery is the lesson set to man to be learned during the ages of incarnation, failing which he is remanded to the lives, to do his task over again many times, perhaps, before he succeeds in the accomplishment by which man becomes a god.

Right here a difference that had been widening as the instructions went on, grew so marked as actually to delay the progress of the class. Part of the members seemed to lose in a degree their desire to progress; a part became careless of the drill that was absolutely necessary if they proceeded — in fact, all seemed disconcerted but Elsie, who grew more and more fearless as she grasped more and more fully the knowledge that lies behind the veil. This condition was the result of direct resistance from the keepers and guardians, ‘who, like the flaming sword of Genesis, keep off the timid and weak. Bulwer tells us of a “dweller on the threshold,” and all writers who write from knowledge always intimate what may be expected by the explorer into untried regions.

There was also a singular difference between the action of Elsie and her companions in passing into the hypnotic state. Her associates all seemed to surrender passively to the guidance of the master-will without volition of their own, as one submits to be blindfolded and led by another. But Elsie, simply by the force of her own will, appeared to consent or comply with the request of the Master, and whatever she did on the psychic plane was with the full sense of self-consciousness. This explanation seems necessary in view of what followed. The old professor often looked steadily at her in a sort of dazed way, but whatever he saw he did not confide to anyone else.[52]

Phelon’s Theosophical teachings would influence Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz.[53] The Scarecrow, Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion might even be interpreted as Mind, Soul, and Selflessness. A version of the Theosophical Trinity (Atma-Buddhi-Manas, or soul, intellect, mind.) The perils encountered on the Yellow Brick Road are a mirror of the spiritual path that Blavatsky describes in The Voice Of The Silence (1889): “There is but one road to the Path; at its very end alone the “Voice of the Silence” can be heard. The ladder by which the candidate ascends is formed of rungs of suffering and pain.”[54] It is not much of a stretch to see in the titular Wizard something of a “Dweller on the Threshold.” The “entity” within ourselves that denies access to a spiritual goal, as W.Q. Judge states:

When the student has at last gotten hold of a real aspiration and some glimmer of the blazing goal of truth where Masters stand and has also aroused the determination to know and to be, the whole bent of his nature, day and night, is to reach out beyond the limitations that hitherto had fettered his soul. No sooner does he begin thus to step a little forward, than he reaches the zone just beyond mere bodily and mental sensations. At first the minor dwellers of the threshold are aroused, and they in temptation, in bewilderment, in doubt or confusion, assail him. He only feels the effect, for they do not reveal themselves as shapes. But persistence in the work takes the inner man farther along, and with that progress comes a realization to the outer mind of the experiences met, until at last he has waked up the whole force of the evil power that naturally is arrayed against the good end he has set before him. Then the Dweller takes what form it may. That it does take some definite shape or impress itself with palpable horror is a fact testified to by many students.[55]

[1] National Archives at Chicago; Chicago, Illinois; ARC Title: Petitions for Naturalization, 1906 – 1991; NAI Number: 6756404; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21. “Incoming Steamers.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) February 27, 1906.

[2] Baum, Maud Gage. In Other Lands Than Ours. Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints. New York, New York. (1983): 5, 13-15.

[3] “An Unforgettable Book.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 10, 1906; “Jurgis Rudkus And ‘The Jungle.’” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 3, 1906.

[4] “The A Club’s Object.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) February 11, 1906; “Review: The Cage.” The Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) March 2, 1907; Twain, Mark. Autobiography Of Mark Twain: Volume II. University Of California Press. Berkeley, California. (2013): 564.

[5] Gomez, Adam. “Deus Vult: John L. O’Sullivan, Manifest Destiny, and American Democratic Messianism.” American Political Thought. Vol. I, No. 2 (September 2012): 236–262.

[6] Mannherz, Julia. Modern Occultism In Late Imperial Russia. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York. (2012): 21.

[7] Hamerow, Theodore S. “History and the German Revolution of 1848.” The American Historical Review. Vol. LX, No. 1 (October 1954): 27–44.

[8] Daniel, Frederick S. “The Unifying Of Italy.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XXXVII, No. 1 (January 1894): 37-47.

[9] Gilman, Sander L. “Karl Marx and the Secret Language of Jews.” Modern Judaism. Vol. IV, No. 3 (October 1984): 275-294.

[10] Mannherz, Julia. Modern Occultism In Late Imperial Russia. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York. (2012): 21-47.

[11] Sharp, Lynn L. Secular Spirituality: Reincarnation and Spiritism in Nineteenth-Century France. Lexington Books. Lanham, Maryland. (2006): 52; Monroe, John Warne. “The Invention And Development Of Spiritism, 1857-1869.” In Laboratories of Faith: Mesmerism, Spiritism, And Occultism In Modern France. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York. (2008): 95-149; Monroe, John Warne. “Crossing Over: Allan Kardec And The Transnationalisation Of Modern Spiritualism.” In (ed.) Gutierrez, Cathy. Handbook Of Spiritualism And Channeling. Brill. Leiden, Netherlands. (2015): 248-93.

[12] Henry Steel Olcott writes: “As early as 1857 the Faculty of Harvard University pronounced the opinion that ‘any connection with spiritualistic circles, so called, corrupts the morals, and degrades the intellect;’ and they even had the effrontery to say that they deemed it ‘their solemn duty to warn the community against this contaminating influence, which surely tends to lessen the truth of man, and the purity of woman.’” [Olcott, Henry S. People From The Other World. American Publishing Company. Hartford, Connecticut. (1875): v.]

[13] Honeck, Mischa. “‘Freemen Of All Nations, Bestir Yourselves’: Felice Orsini’s Transnational Afterlife And The Radicalization Of America.” Journal Of The Early Republic. Vol. III, No. 4 (Winter 2010): 587-615.

[14] Garrigou-Kempton, Emilie. “Hysteria In Lourdes And Miracles At The Salpêtrière: Making Sense Of The Inexplicable In Charcot’s La Foi Qui Guérit And In Zola’s Lourdes.” In Quand La Folie Parle: The Dialectic Effect of Madness in French Literature Since the Nineteenth Century. (eds.) Gillian Ni Cheallaigh, Laura Jackson, Siobhan McIlvanney. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, England. (2014): 53-73.

[15] Altherr, Thomas L. “‘A Convention of ‘Moral Lunatics’: The Rutland, Vermont, Free Convention Of 1858.” Vermont History. Vol. LXIX. (2001): 90-104.

[16] “Free Convention.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 29, 1858.

[17] Davis writes: “Each human spirit possesses within itself an eternal affinity of parts and powers; which affinity there exists nothing sufficiently superior, in power and attraction, to disturb, disorganize, and annihilate. These are evidences with which the world is not familiar; but they are plain and demonstrative; and are destined to cause great happiness and elevation among men.” Davis, Andrew Jackson. The Great Harmonia. Vol. I. (Fourth Edition.) Sanborn, Carter, & Bazin. Boston, Massachusetts. (1855): 189.

[18] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8509. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Lyman F. Baum. (9/2/92); Rogers, Katherine M. L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz: A Biography. St. Martin’s Publishing Group. New York, New York. (2002): 13, 50; Schwartz, Evan I. Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (2009): 207.

[19] Judge, William Quan. “Letters Of W. Q. Judge.” The Theosophist. Vol. LII No. 12 (September 1931): 752-756.

[20] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1285. (website file: 1A:1875-1885); William B. Shelley. [7/27/1882]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1286. (website file: 1A:1875-1885); James Harvey Cables. [7/27/1882]; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1287. (website file: 1A:1875-1885); Josephine Warner Cables. [7/27/1882.]

[21] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol I., No. 1. (April 1886): 30-32; Bowen, Patrick D. A History of Conversion to Islam in the United States: Vol. I. Brill. Leiden, Netherlands. (2015): 78.

[22] The first Congress of the National Liberal League was held in Philadelphia in 1876. The second Congress was held in Rochester, New York in 1877, with an increased attendance. [Underwood, B.F. “An Open Letter To Col. Ingersoll.” The Index. Vol. ??, No. ?? (November 12, 1885): 232-234.]

[23] Judge, William Quan. “Letters of W. Q. Judge.” The Theosophist. Vol. LII, No. 8 (May 1931): 191-197.

[24] The Occult Word. Vol. I, No. 1 (April 1884.)

[25] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1195. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) WJ.D. Buck. (5/71/82); “A President Of Shadows.” The Butte Daily Post. (Butte, Montana) April 25, 1896; “April 27, 1886—Dear Olcott.” Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951)

[26] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. I, No. 1 (April 1886): 30-32.

[27] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3274. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Matilda Joslyn Gage. (12/17/1885.)

[28] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 8509. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Lyman F. Baum. (9/2/92.)

[29] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 220. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Stanley B. Sexton. (9/18/1879); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3050. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Jakob Bonggren (11/10/1884); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3051. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) William Phelon. (11/10/1884); Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3052. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Mira Morse Phelon (11/10/1884);

“Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol I., No. 1. (April 1886): 30-32; Bonggren, Jakob. “The Wisdom Religion.” The Inter Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) April 12, 1889; “No Mourning or Words of Sorrow.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 26, 1896.

[30] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3231. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Maud L. Brainard.

[31] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 118. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Rev. W.H. Hoisington. (5/10/1876.) [Janesville, Wisconsin.] “Local Matters.” The Iowa County Democrat. (Mineral Point, Wisconsin) March 2, 1870.

[32] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3292. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Lauretta H. Hoisington. (4/11/1885); “Faces of Friends: Lauretta H. Cutter Hoisington.” The Temple Artisan. Vol. X, No. 3 (August 1909): 45-47.

[33] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3614. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Antoinette V. Wakeman. (4/17/1886); “Mrs. Antoinette Van Hoesen Wakeman.” In A Woman Of The Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied By Portraits of Leading American Women In All Walks of Life. (eds.) Willard, Frances E; Livermore, Mary A. Charles Wells Moulton. Chicago, Illinois. (1893): 738-739.

[34] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4421. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Mercie Thirds. [Chicago. (4/8/1888); “Theosophic Adepts.” The San Francisco Call And Post. (San Francisco, California) January 19, 1891; “Local Criticism Of A Mystic Body.” The San Francisco Call And Post. (San Francisco, California) February 16, 1895.

[35] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4741. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Gertrude Piper. [Chicago. (1/5/1889); “His Strange Hypnotic Powers.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) March 30, 1894.

[36] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3615. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Anna Byford Leonard. [1832 Indiana Avenue. Chicago, Illinois. Chicago T.S. (4/17/1886)]; “Mrs. Leonard’s Home Opens.” The Theosophical News. Vol. I, No. 25 (December 7, 1896): 1.

[37] “Great Chicago Riot.” The Sun. (New York, New York) May 5, 1886; “Denounced From Pulpit.” The Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois) May 10, 1886; “The Anarchists And Diplomacy.” The Inter-Ocean. (Chicago, Illinois) May 14, 1886.

[38] McDonald, Flora. “Divine Illumination.” The Saint Paul Globe. (Saint Paul, Minnesota) April 24, 1887.

[39] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3050. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) William Phelon. (11/10/1884); “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol II., No. 7. (October 1887): 222-224.

[40] McDonald, Flora. “Divine Illumination.” The Saint Paul Globe. (Saint Paul, Minnesota) April 24, 1887.

[41] “The Mystery of Cloomber.” The Portsmouth Evening News. (Hampshire, England) January 3, 1889.

[42] Judge, William Quan. “Contemporary Literature and Theosophy.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 3 (June 1888): 92-94.

[43] Holloway writes: “.” [Holloway, Laura C. “Theosophy In Literature.” The Times Union. (Brooklyn, New York.) March 16, 1889.]

[44] “The Mystery of Cloomber.” The Portsmouth Evening News. (Hampshire, England) January 3, 1889.

[45] “Trite Theosophy.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) October 14, 1888.

[46] Jekyll states his motives for the experiment: “With every day, and from both sides of my intelligence, the moral and the intellectual, I thus drew steadily nearer to that truth, by whose partial discovery I have been doomed to such a dreadful shipwreck: that man is not truly one, but truly two […] I, for my part, from the nature of my life, advanced infallibly in one direction and in one direction only. It was on the moral side, and in my own person, that I learned to recognize the thorough and primitive duality of man; I saw that, of the two natures that contended in the field of my consciousness, even if I could rightly be said to be either, it was only because I was radically both […] If each, I told myself, could be housed in separate identities, life would be relieved of all that was unbearable; the unjust might go his way, delivered from the aspirations and remorse of his more upright twin; and the just could walk steadfastly and securely on his upward path, doing the good things in which he found his pleasure, and no longer exposed to disgrace and penitence by the hands of this extraneous evil. It was the curse of mankind that these incongruous faggots were thus bound together—that in the agonized womb of consciousness, these polar twins should be continuously struggling. How, then were they dissociated?” [Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde. Charles Scribner’s Sons. New York, New York. (1886): 106-107.]

[47] Blavatsky writes: “It is curious to note that Mr. Stevenson, one of the most powerful of our imaginative writers, stated that he is in the habit of constructing the plots of his tales in dreams.” [Blavatsky, Helena P. “The Signs Of The Times.” Lucifer. Vol. I, No. 2 (October 15, 1887): 83-89.]

[48] Blavatsky, Helena P. The Secret Doctrine Vol. II: Anthropogenesis. The Theosophical Publishing Company. London, England. (1888): 317;

[49] Blavatsky states: “The future of the Lower Manas is more terrible, and still more terrible to humanity than to the now animal man. It sometimes happens that after the separation the exhausted Soul, now become supremely animal, fades out in Kâma-Loka, as do all other animal souls. But seeing that the more material the human mind, the longer it lasts, in that intermediate stage, it frequently happens that after the actual life of the soulless man is ended, he is again and again reincarnated into new personalities, each one more abject than the other. The impulse of animal life is too strong; it cannot wear itself out in one or two lives only. In rarer cases, however, something far more dreadful may happen. When the lower Manas is doomed to exhaust itself by starvation; when there is no longer hope that even a remnant of a lower light will, owing to favorable conditions––say, even a short period of spiritual aspiration and repentance––attract back to itself its Parent Ego, then Karma leads the Higher Ego back to new incarnations. In this case the Kâma-Mânasic spook may become that which we call in Occultism the ‘Dweller on the Threshold.’ This ‘Dweller’ is not like that which is described so graphically in Zanoni, but an actual fact in nature and not a fiction in romance, however beautiful the latter may be. Bulwer must have got the idea from some Eastern Initiate. Our ‘Dweller,’ led by affinity and attraction, forces itself into the astral current, and through the Auric Envelope of the new tabernacle inhabited by the Parent Ego, and declares war to the lower light which has replaced it. This, of course, can only happen in the case of the moral weakness of the personality so obsessed. No one strong in his virtue, and righteous in his walk of life, can risk or dread any such thing; but only those depraved in heart. Robert Louis Stevenson had a glimpse of a true vision indeed when he wrote his Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. His story is a true allegory. Every Chela would recognize in it a substratum of truth, and in Mr. Hyde a ‘Dweller,’ an obsessor of the personality, the tabernacle of the ‘Parent Spirit.’” [Blavatsky, Helena P. Collected Writings Volume XII (1889-1890.) Theosophical Publishing House. Wheaton, Illinois. (1980): 636-638. [E.S. Instruction No. III.]]

[50] Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. The Key To Theosophy. Theosophical Publishing Company. New York, New York. (1896): 63-64; Ludlow, William. “Theosophy.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 24, 1892; Cavé. “Questions and Answers.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. IV, No. 2 (June 1898): 1-4; “Fifty Years.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIII. No. 3. (January 1926.) 209-211.

[51] Phelon, William P; Phelon, Mira Morse. Three Sevens, A Story Of Ancient Initiations. The Hermetic Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1889): 6-7.

[52] Phelon, William P. A Witch Of The Nineteenth Century. The Hermetic Publishing Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1893): 86-89.

[53] Rogers, Katherine M. L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz: A Biography. St. Martin’s Publishing Group. New York, New York. (2002): 13, 50; Schwartz, Evan I. Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. (2009): 207.

[54] Blavatsky, H.P. The Voice Of The Silence. The Theosophical Publishing Company. London, England. (1889): 15.

[55] Judge, William Quan. “The Dweller Of The Threshold.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 9 (December 1888): 281-284.