The Theosophists have long had a fascination with lost, ancient civilizations in Central and South America. According to Blavatsky, she traveled to South America in the 1850s to learn occult secrets.[1] (One account claims that she was with an Englishman whom she had met in Germany and a Hindu “Chela,” whom she came across at the Mayan ruins at Copán, Honduras.)[2] For Blavatsky, the similarities of the rites, ceremonies, traditions, and even the names of the gods, between the ancient peoples of Central and South America, and the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians, was sufficient proof that the “New World” was peopled by a colony which somehow found its way across the Atlantic.[3]

William Quan Judge, leader of the American Theosophists, was no less fascinated by this hypothesis. In the early 1880s, Judge began his connection with the Carupano Silver Mining Company (New York) which had a base of operation near Carupano, Venezuela.[4] It was a commercial endeavor but had elements of the occult. The United States and Britain used the gold standard. In 1878 the United States passed the Bland-Allison Act (1878.) The direct result was the enormous production and monetization of silver.[5] In June 1881 Judge made his first South American trip in the interest of that enterprise, staying there for about a month before returning to New York (on July 24, 1881.)[6] Judge states: “[R.B. Allen of Philadelphia] went out to do some mining in South America for my clients. He didn’t do it right. I went to Venezuela after him, and he came back to Venezuela and disappeared.”[7] Judge records his experience in Venezuela in his story, “A Weird Tale.”[8] While in Venezuela, Judge chanced upon Jim Connelly, who was reporting on assignment for the New York Times. Connelly writes: “I was not a little astonished when one day he appeared in La Guayra Venezuela where I happened to be as the attorney representing a mining company holding certain valuable concessions from the Venezuelan government. He had come to straighten out some snarl the company had got itself into or secure it in some jeopardized rights.”[9] (It is likely that Judge is the “company’s agent” referred to in Connelly’s article, “A Land of Follies and Sin.”)[10]

Aside from the potential financial reward, there was a mystical element to the journey. There were legends concerning the place of his visit; one tradition claimed that in Venezuela one could find “subterranean passage[s] which leads to Cuzco,” where “large vaults filled with treasure” were buried beneath the great ruins of the Inca.[11] (It was around the time that Judge took a steamer for South America, that Frank H. Cushing promised to “create a historical sensation” with his statements regarding ancient Mexican history.)[12] From reading Isis Unveiled, and his talks with Blavatsky, Judge already believed that the history of the American continents (North and South,) and the civilizations they held, were at odds with orthodox history. But every day, it seemed, normative science was validating everything Blavatsky had taught. While in Venezuela, one of the men in the mine affair asked Judge to go to Mexico to look at property there on his behalf.[13] It was in the same region that Blavatsky referenced in Isis Unveiled.[14]

This inquiry into America’s ancient past was not limited to students of esoterica. During the winter of 1882, Ignatius Donnelly published his wildly popular, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, in which he claims for America the lost kingdom mentioned by Plato. On March 18, 1882, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle devoted several columns to the review in which it stated: “The Flood legends all duplicate the destruction of Atlantis, and they passed America, not by way of the Aleutian Islands, or through Buddhists in Asia, but were derived from actual knowledge possessed by the people of America.”[15] At the same time, Frank Cushing was making waves in America by hosting a delegation of Zuni in Boston, to perform their rituals for the benefit of Boston city leaders, clergy, and Harvard professors.[16] The New York Times mockingly stated. “Boston has something better than early English or even the Italian Renaissance. It has the Zuni religion.” The age of the Zuni was inferred by their “strange and mystic” rituals, suggesting a time for the start of their civilization that was at odds with contemporary scientific consensus.[17] The article added: “If Col. Olcott and Mme. Blavatsky had stayed in the United States, instead of going to India in search of the true faith among the Brahmins, they might have found a religion more truly bric-à-brac than anything they will discover in Bombay.”[18] Cushing later returned to New Mexico with the Zuni delegation. Sylvester Baxter, a Boston journalist writing for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine was dispatched to interview Cushing and write about his findings.[19] While there, Baxter learned of a legend of a fair-skinned people who dwelled amongst the Zuni.[20] (Baxter would join the Theosophical Society in 1885.)[21] The journalist-Theosophist, David A. Curtis, would also speculate on America’s ancient past while reporting on “The Mississippi River Problem” (also for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine,) postulating that recently-discovered ruins found by native Mounds suggested a lost ancient civilization.[22] (Curtis may have been inspired by fellow Theosophist, Albert Rawson, who was among the first to champion further scholarship of the civilizations of American antiquity with an essay on the “mound-builders.”)[23] Curtis’s article would be cited in Ragnarök: The Age Of Fire And Gravel, Ignatius Donnelly’s 1883 follow-ap to Atlantis.[24] [Read more about this here.]

Next came Augustus Le Plongeon, who wrote Sacred Mysteries Among The Mayas And The Quiches in 1886.[25] It was an account of the explorations in the Yucatan he had embarked on with his wife, and fellow explorer, Alice Le Plongeon. “It seems a pity that the American Government cannot send out a properly equipped expedition, but perhaps this is too much to expect,” said the review for it in The Theosophist in late 1887.[26] The hidden history of the region was certainly on the mind of Blavatsky at the time. She even referenced a hidden Lodge of Masters located in the Americas to Charles Johnston when they first met in the spring of 1887.

Then she told me something about other Masters and adepts she had known—for she made a difference, as though the adepts were the captains of the occult world, and the Masters were the generals. She had known adepts of many races, from Northern and Southern India, Tibet, Persia, China, Egypt; of various European nations, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, English; of certain races in South America, where she said there was a Lodge of adepts. “It is the tradition of this which the Spanish Conquistadores found,” she said, “the golden city of Manoah or El Dorado. The race is allied to the ancient Egyptians, and the adepts have still preserved the secret of their dwelling-place inviolable. There are certain members of the Lodges who pass from centre to centre, keeping the lines of connection between them unbroken. But they are always connected in other ways.”[27]

In the summer of 1888 the Brooklyn Theosophist, Laura C. Holloway, interviewed Alice Le Plongeon for The New York Herald.[28] The connection was kept throughout 1889, as both Holloway and Le Plongeon traveled in the same circle as Auguste Kraus, the wife of Anton Seidl (the conductor of the German Opera at the Metropolitan Opera House.)[29]

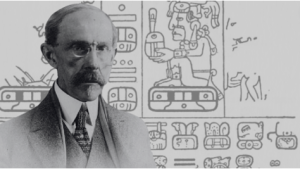

In the middle of March 1889, William E. Gates, the young President of the newly-formed Cleveland Branch went to New York and called on W.Q. Judge. Gates was “an intelligent young Southerner,” who joined the Society in November 1887.[30] He was also a student of Sanskrit who graduated from John Hopkins University with high honors in 1886.[31] He was involved in a legal dispute with the Hammond Typewriter Company and Judge, a lawyer, helped him with the case. Not long after, Gates pivoted from Sanskrit to studying the culture of the Maya.[32]

The introduction of the Le Plongeons to Blavatsky may have been made by Holloway. Whatever the case may be, on September 6, 1890, the Le Plongeons visited the Lecture Hall of the new Headquarters and “gave a short and concise sketch of the history of the Mayas, their customs and their language,” showing their connection with “the Hindus and other Eastern peoples” in a striking manner.[33] “By no means the least interesting part of the lecture,” The Pall Mall Gazette stated, was the account given of the stone inscriptions that had been deciphered after much work. “Some of these relate to a cataclysm which destroyed and submerged a vast continent with its millions of inhabitants, doubtless belonging to that mysterious race—whose history is now regarded almost as a myth —known to us under the name of the Atlanteans.”[34] Charles Johnston, who met the Le Plongeons at this time, must have been impressed. Le Plongeon’s Sacred Mysteries would be among the works collected in the New York Theosophical Society’s Library catalog.[35]

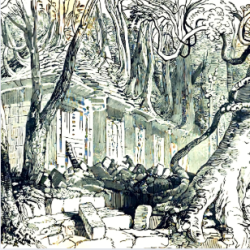

In 1892 Judge revisited the topic of ancient civilizations in Central America. “In Central America, there are vast masses of ruins among which trees of considerable girth are now growing,” Judge writes. “In other districts, the remains of well-made roads are sometimes found creeping out from tangled underbrush and disappearing under a covering of earth […] On the Pacific Coast, in one of the Mexican States, there is old and new San Blas, the one on the hill, deserted and almost covered with trees and debris of all sorts which is surely constructing a covering that will ere long be some feet in thickness.”[36] This topic had echoes in his “Occult Diaries.” An entry made on January 3, 1895, seemingly suggested that he was in communication with Blavatsky from beyond the grave. The entry makes allusion to America and a little-known Lodge of adepts (presumably in South America.)[37] After Judge’s death in March 1896, Katherine Tingley succeeded him as the “Outer Head” of the Esoteric Section (of the Theosophical Society in America.) Ernest Temple Hargrove succeeded him as President of the exoteric organization. When Tingley announced a global “Theosophical Crusade,” she stated that part of its purpose was to “carry evidences of the great civilizations of the past in America as yet unknown to scientists and collated by our members in Central and South America.”[38] Hargrove, for his part, made several mentions of The Popol Vuh during the summer of 1896.[39]

After the death of Judge, Charles and Vera Johnston sided with the American Theosophists. By the end of the year they would relocate to New York at the insistence of C.A. Griscom, Jr.[40] Johnston, likewise, investigated the mystery of ancient civilizations in America. “It may be suggested, in passing, that a part of the substance of The Popol Vuh is so ancient that it contains memories of the spiritual history and powers of the Third Race, and also of the sinking of Atlantis,” Johnston would write.[41] When the second schism happened within the Theosophical Society in America between Tingley and the Griscom faction, Johnston sided with the Griscoms.

Sun Dance Priests.[42]

In 1902 Johnston accepted an invitation from John H. Singer to visit Colony, Oklahoma, where he had established an industrial training school for the Cheyenne.[43] While there, he investigated the “Sun Dance” ritual.[44] Johnston delivered an address at the Museum of Natural History on the evening of January 13, 1903, under the auspices of the Sequoya League, an organization created by Charles F. Lummis for the promotion of Native American rights.[45] His talk, “The Sun Dance” would be centered on his research among the Cheyenne at Colony, Oklahoma.

(Left) Museum Reading Room-Library.[46]

(Right) Front View of the Skull, Tibia, and Femur of Adult Skeleton, with Maxilla of Child in the foreground.[47]

The Museum was steadily becoming a favorite hub for men of science and education. Gary N. Calkins, Columbia University’s professor of invertebrate zoology recently helped curate the protozoa exhibit. There were lectures by anthropology professors Franz Boas, and Livingston Farrand, and a course taught by zoologist, Henry E. Crampton.[48] Three of these men (Calkins, Farrand, and Crampton,) would participate in the New York Theosophical Society’s year-long salon, “Talks On Religion.”[49] A topic on many minds at this time was the discovery of a skull found in Lansing, Kansas, which suggested a much earlier date for human settlement in Western Hemisphere.[50] In fact, it revived “the question of the antiquity of man in America.”[51] Johnston incorporated this topic into his talk, stating:

The real theme of the Sun Dance is an historical and religious tradition, expressed through ritual comparable to the ritual of Masonry, and accompanied by groups of significant melodies. I am inclined to believe that the historical tradition among the Cheyenne contains reminiscences of the glacial age, which may have ended ten or twelve thousand years ago. This is the more credible, because the Lansing skull, recently found in a deposit of inter-glacial age, is of the same type as the skulls of modern Indians, like the Cheyenne, for instance, showing that the same race has inhabited the United States since that period […] [Motse Iyoeff] also taught or confirmed the teaching of the immortality of the soul. When we remember how dimly this teaching is suggested in the Old Testament, we can see how much spiritual light is implied by its presence among the aboriginal races of America. The prophet taught that evil deeds were punished by suffering in this life, and that, after death, liberated souls went to a starry world where the Great Spirit is. The tone of religious thought among the red races of America may be illustrated by a prayer of great antiquity preserved in the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Quichés of Guatemala.[52]

Naturally, Johnston grew close to Clem and his family; he would often go bird-watching with Ludlow Griscom (the eldest son of Clem and Genevieve Griscom) in the environs of New York.[53] Both were members of The Linnaean Society, but Ludlow would make a career out of it, holding important positions at the American Museum of Natural History and Harvard.[54] In February 1917 Ludlow sailed for the first time to Central America (Cuba, Panama, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua,) where he would become the leading authority on the birds of the region. During the Great War, he was transferred to Military Intelligence Headquarters in Washington, D.C., becoming an executive officer for the newly formed Propaganda Section. He continued birding even when transferred to Europe.[55] When Ludlow returned to the United States he would publish his first major ornithological work, The Birds Of The New York City Region.[56] (Charley reviewed it for The New York Times.)[57]

William E. Gates.

Johnston, meanwhile, continued writing about the theorized lost civilization in the Yucatan. “There were schools of occultism indigenous to the American continent, and possessing a part at least of The Secret Doctrine, as made known to us through The Stanzas of Dzyan,” Charley writes in 1919. “The parts of The Secret Doctrine are contained in a Scripture in the Quiché language, a tongue still spoken over hundreds of square miles in southern Mexico and Guatemala; a language obviously of Atlantean origin.[58] Such writings were not limited to Theosophical publications. In the article for the November 1920 issue of The Atlantic, “The Two Mexicos,” Johnston writes: “[In Mexico, one] finds many traces of a far more spiritual religion; and deeply interesting fact is, that this older and perhaps primeval worship seems still to survive among remoter tribes; to survive with a spirit and a ceremonial which vividly suggests the Rig Veda.”[59] It was around this time (the summer of 1920) that William E. Gates, now Professor of American Archaeology and Linguistic School of Antiquity at Point Loma, formed The Maya Society with the anthropologist Herbert J. Spinden.[60] Perhaps it was a call to action. (Percy H. Fawcett, who joined the Theosophical Society in 1886, made his first solo trip in search of the legendary lost South American city of “Z” in 1920.)[61]

Left to right, back row: McClurg, Spinden; front row, Mason, Whiting, Griscom.[62]

“Tulum’s Temple of the Frescoes.” 1926.[63]

Ludlow Griscom would work with Spinden six years later in an expedition to the Yucatan to “find cities buried in the jungle.”[64] (He was following in the footsteps of his grandfather, William Ludlow, who discovered what he believed to be remnants of a lost civilization in the Black Hills.) They were joined by Gregory Mason (former editor of Outlook,) Frank Whiting, and Ogden Trevor McClurg. They set sailed from New Orleans on January 9, 1926.[65] Their exploits filled the pages of The New York Times in the early part of the year.[66] During the expedition, Griscom and Spinden discovered the ruins of Cinco Puertos and the unexcavated temples at Tulum. “More than anything we have found these paintings gave me a creepy feeling of the nearness of the ancient builders, as if in a dark corner of this temple I had glimpsed a be-feathered priest at his occult rites,” Mason writes in his account of the voyage, Silver Cities Of Yucatan.[67] Perhaps there was a Theosophical connection.

[1] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. I. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 547-548, 595-598.

[2] H. S. O. “Traces Of H. P. B.” The Theosophist. Vol. XIV, No. 7 (April 1893): 429-431.

[3] In Isis Unveiled, Blavatsky references John L. Stephens’s Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan. [Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. I. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 547-548, 556, 595-598.] As Stephen’s noted, questions were now being asked about the “first peopling of America.” Some said the Native Americans were a separate race, “not descended from the same common father with the rest of mankind.” Others ascribed their origin to “some remnant of the antediluvian inhabitants of the earth who survived the deluge which swept away the greatest part of the human species in the days of Noah.” In 1807 Alexander Von Humboldt published his theory that South America and Africa were once a connected. [See: Harvey, Eleanor Jones. Alexander Von Humboldt And The United States: Art, Nature, And Culture. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2020): 27.] Having accepted that the two continents had been “rent asunder by the shock of earthquake,” the fabled island of Atlantis had been “lifted out of the ocean,” and into the popular imagination. [Stephens, John L. Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan: Vol. I. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1841): 96.] Stephens told the story of a mysterious city, as recounted to him by a Spanish Padre, who swore to him that he had seen it with his own two eyes. Stephens writes: “He had heard of it many years before at the village of Chajul and was told by the villagers that from the topmost ridge of the sierra this city was distinctly visible. He was then young, and with much labor climbed to the naked summit of the sierra, from which at a height of ten or twelve thousand feet, he looked over an immense plain extending to Yucatan and the Gulf of Mexico and saw at a great distance a large city spread over a great space, and with turrets white and glittering in the sun. The traditionary account of the Indians of Chajul is, that no white man has ever reached this city; that the inhabitants speak the Maya language, are aware that a race of strangers has conquered the whole country around and murder any white man who attempts to enter their territory. They have no coin or other circulating medium; no horses, cattle, mules, or other domestic animals except fowls, and the cocks they keep underground to prevent their crowing being heard.” [Stephens, John L. Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan: Vol. II. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1841): 195-1996.]

[4] United States. Bureau of the Mint. “Annual Report of the Director of the Mint To The Secretary Of The Treasury For The Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1882.” The Report Of The Director Of The Mint. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. (1882): 140-142.

[5] United States Congress Special Committee on the Investigation of Silver. Silver: Hearings Before a Special Committee on the Investigation of Silver. U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. (1939): 262-263.

[6] William Q. Judge to Damodar K. Mavalankar, 26 July 1881, in Damodar And The Pioneers Of The Theosophical Movement, Sven Eck (Adyar, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1965): 63.

[7] “Base Spirits Beset Judge.” The Sun. (New York, New York) April 5, 1894.

[8] Judge writes: “One very warm day in July 1881, I was standing at the vestibule of the Church of St. Theresa in the City of Caracas, Venezuela. This town was settled by the Spaniards who invaded Peru and Mexico and contains a Spanish-speaking people. A great crowd of people were at the door and just then a procession emerged with a small boy running ahead and clapping a loud clapper to frighten away the devil. As I noticed this, a voice in English said to me ‘curious that they have preserved that singular ancient custom.’ Turning I saw a remarkable looking old man who smiled peculiarly and said, ‘come with me and have a talk.’ I complied and he soon led me to a house which I had often noticed, over the door being a curious old Spanish tablet devoting the place to the patronage of St. Joseph and Mary. On his invitation I entered and at once saw that here was not an ordinary Caracas house. Instead of lazy dirty Venezuelan servants, there were only clean Hindoos such as I had often seen in the neighboring English Island of Trinidad; in the place of the disagreeable fumes of garlic and other things usual in the town, there hung in the air the delightful perfumes known only to the Easterns. So I at once concluded that I had come across a delightful adventure.” [Judge, “A Weird Tale Pt. I.”] Judge says it was a July day. The festival he is describing is most likely the “Diablos Danzantes.” [Judge, William Quan. “A Weird Tale Pt. I.” The Theosophist. Vol. VI, No. 75 (July 1885): 237-238; Judge, William Quan. “A Weird Tale Pt. II.” The Theosophist. Vol. VII, No. 75 (December 1885): 202-206.]

[9] Connelly, J.H. “Our Friend And Guide.” Theosophy. Vol. XI, No. 3 (June 1896): 85-88.

[10] Connelly writes: “The Custom-house authorities still pursue their playful predatory contest with not only the outside world, but the interests of their own country, as is amply illustrated by a still unsettled case in the Laguayra branch of that service. A company organized in New York for the operating of a mine at Carupano imported some six tons of machinery, which was landed at Laguayra about four months since, there to be reshipped for Carupano. The tariff laws of Venezuela then prescribed that all machinery imported for mining purposes should be admitted free of duty, a long-standing concession which was intended when originally made to encourage the development of the great mineral resources of the country. Not only had the company that legal right, but a specific provision to the same effect was contained in the conditional concession or grant which they held from the Government. Notwithstanding all this, the Laguayra Custom-house officials seized upon the six tons of machinery and demanded duties. The company’s agent protested, appealed to the law and the special authority he held, but all without avail. All the answer he could get was that the President must decide the matter, and until it was brought to his attention, and he could be got to issue an order on the subject no relief could be had, and no arrangement would be entered into except upon the basis of the payment of an enormously high duty upon the value of the machinery.” [ J.H.C. “A Land of Follies and Sin.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) August 30, 1881.]

[11] Squier, Ephraim George. Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas. Macmillan and Company. London, England. (1878): 281-282.

[12] “Mr. Frank H. Cushing.” The Boston Post. (Boston, Massachusetts) June 30, 1881; “Coming to Boston With Strange Rites.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) March 1, 1882.

[13] “Letters of W. Q. Judge.” The Theosophist. Vol. LII No. 12 (September 1931): 752-756.

[14] Blavatsky writes: “Without stopping to discuss whether Hermes was the “Prince of postdiluvian magic,” as des Mousseaux calls him, or the antediluvian, which is much more likely, one thing is certain: The authenticity, reliability, and usefulness of the Books of Hermes—or rather of what remains of the thirty-six works attributed to the Egyptian magician—are fully recognized by Champollion, junior, and corroborated by Champollion-Figeac, who mentions it. Now, if by carefully looking over the kabalistical works, which are all derived from that universal storehouse of esoteric knowledge, we find the facsimiles of many so-called miracles wrought by magical art, equally reproduced by the Quichès; and if even in the fragments left of the original Popol-Vuh, there is sufficient evidence that the religious customs of the Mexicans, Peruvians, and her American races are nearly identical with those of the ancient Phoenicians, Babylonians, and Egyptians […] The Toltecs themselves descended from the house of Israel, who were released by Moses, and who after crossing the Red Sea, fell into idolatry. After that, having separated themselves from their companions, and under the guidance of a chief named Tanub, they set out wandering, and from one continent to another they came to a place named the Seven Caverns, in the Kingdom of Mexico, where they founded the famous town of Tula.” [Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Volume I—Science. J.W. Bouton. New York, New Yok. (1877) 551-552.]

[15] “Atlantis.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) March 18, 1882.

[16] “Coming to Boston With Strange Rites.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) March 1, 1882.

[17] The New York Times stated: “When the Zuni faith was first revealed to man, one of the conditions imposed upon the patriarchs of the tribe was that they should go to the sea-side every month and bring home a quantity of sea-water for incantation purposes. As the region now known as New Mexico was then near the borders of what is now known as the Atlantic Ocean, this was an easy task. But, as all geographers and other scientific persons very well know, the American continent has been steadily rising from the sea, ever since its foundations were laid. It has been estimated by a well-known scientific person that the continent has risen three-quarters of an inch during the last five centuries without making any allowance of the strata of tomato cans and hoop-skirts formed along that portion of the Atlantic sea-board frequented by Summer visitors. If the student of theology will calculate the time required, on this basis, to raise from under high-water mark that portion of the American continent which lies between the Atlantic Ocean at Boston and the country of the Zunis in New-Mexico, he will ascertain with tolerable accuracy the age of the Zuni faith. And this calculation is now being worked out by several Harvard Professors, who will, in time, give the result to the world, showing that the Zuni variety of paganism is so very aged that the Hindu faiths now being imbibed by Olcott, Blavatsky and the other Theosophists may be considered as modern inventions.” [“A Boston Revival.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 31, 1882.]

[18] “A Boston Revival.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 31, 1882.

[19] Haglund, Karl. Inventing The Charles River. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (2002): 120.

[20] Baxter stated in his article: “Many of the beards were of a pale Scandinavian blonde, while the hair was of the color in a number of instances […] Is it not possible that they may point back to a time when a light haired and bearded race existed in America?” [Baxter, Sylvester. “The Father of the Pueblos.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Vol. LXV, No. 385. (June 1882): 72-91.]

[21] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3514. (website file: 1B:1885-1890); Sylvester Baxter. [12/17/1885.]

[22] Curtis writes: “When La Salle out how goodly a land it was, his was the warrant of eviction that drove the red man to make place for the white, as the Mound-builders had made place the Indian in what we call the days old. Yet it must have been only yesterday that the Mound-builders wrought the valley, for in the few centuries have elapsed since then the surface of ground has risen only a few feet—enough to bury their works out of sight. How long ago, then, must it have been that the race lived there whose pavement and cisterns of Roman brick now lie seventy feet underground? And if we cannot answer this question, how shall figure up the sum of the years it has taken for the river to fill the valley a thousand feet deep with silt?” [Curtis, David A. “The Mississippi River Problem.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Vol. LXV, No. 388. (September 1882): 608-614.]

[23] Rawson, Albert L. “Archaeology in America.” The Phrenological Journal. Vol. LVIII, No. 3. (March 1874): 155-160.

[24] Donnelly writes: “Mr. Curtis does not mean that the bricks found in this prehistoric settlement had any historical connection with Rome, but simply that they resemble Roman bricks. These remains, I learn, were discovered in the vicinity of Memphis, Tennessee. The details have not yet, so far as I am aware, been published. Is it not more reasonable to suppose that civilized man existed on the American Continent thirty thousand years ago, (the age fixed by geologists for the coming of the Drift,) a comparatively short period of time, and that his works were then covered by […] debris, than to believe that a race of human beings, far enough advanced in civilization to manufacture bricks, and build pavements and cisterns, dwelt in the Mississippi Valley, in a past so inconceivably remote that the slow increase of the soil by vegetable decay, has covered their works to the depth of seventy feet?” [Donnelly, Ignatius. Ragnarök: The Age of Fire and Gravel. D. Appleton and Company. New York, New York. (1883): 354-355.]

[25] Le Plongeon, Augustus. Sacred Mysteries Among The Mayas And The Quiches. Robert Macoy. New York, New York. (1886.)

[26] “Reviews.” The Theosophist. Vol. IX, No. 99 (December 1887): 181-189.

[27] Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part I.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. V, No. 12 (April 1900): 221-225; Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part II.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI, No. 1 (May 1900): 2-5; Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part III.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI, No. 2 (June 1900): 22-26; Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part IV.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI, No. 3 (July 1900): 44-46.

[28] “[Holloway:] ‘Then you give credence to the theory that there was a such a catastrophes as the sinking of Atlantis?’[Plongeon:] ‘Certainly. That continent existed between America and the western coast of Africa and Europe. In a Maya manuscript still in existence there is an account of that awful cataclysm, and these interesting monuments, with their inscriptions so full of historical revelations, with the key of their decipherment known, are able to give us the entire history of the intellectual development of the human family. What makes it more delightful, too, is that this history is free from the myths and fables, creations of untutored and credulous imaginations or work of crafty philosophers, which we find in the sacred books of the Asiatic countries. We have inherited myths bequeathed to us as revelations from on high, and he origin of which we did not know until they stood revealed in the excavated cities of Yucatan and the crumbled walls of the temples of Maya.’” [“A Woman Explorer.” The Transcript-Telegram. (Holyoke, Massachusetts) July 21, 1888.]

[29] In February 1889, Alice Plongeon and Auguste Kraus attended a reception held by Laura C. Holloway. Literary and musical people were out in numbers, including fellow Theosophist, Ella Wheeler Wilcox. [“Mrs. Holloway’s Reception.” The Times Union. (Brooklyn, New York) February 8, 1889.] In the summer of 1889, Holloway established the Seidl Society (a woman’s club that hosted regular world-class concerts in Coney Island, New York.) [“The Seidl Society.” The Brooklyn Citizen. (Brooklyn, New York) June 16, 1889; Horowitz, Joseph. “A Life In Limbo: Laura Langford and Brooklyn’s Seidl Society.” The Journal Of The Gilded Age And Progressive Era. Vol. XII, No. 1 (January 2014): 80-92.]

There was a connection between the Seidl Society and the Theosophical Society. Elizabeth Chapin and her cousin, Maude Ralston, two of the founding members of the Seidl Society, were also leading members of the Brooklyn Branch of the Theosophical Society. [Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6293. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Lizzie Chapin; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 6294. (website file: 1C:1890-1894) Maude Ralston.] It was said that Holloway once had a vision (which Chapin and Ralston confirmed) while attending a Seidl Society concert at Brighton Beach, whereby the “astral form” of Blavatsky appeared on the platform beside the conductor, Anton Seidl, and in “furious tones” said: “Damn her [Besant] she’s gone into the Catholic Church.’” [Sasson, Diane. Yearning for the New Age. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana. (2012): 239.]

[30] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4240. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) William E. Gates. (11/20/1887.)

[31] “The Hammond Typewriter Company.” The American Stationer. Vol XXVI, No. 17 (October 24, 1889): 1052-1053; Lantz, Emily Emerson. “Maya Society Formed To Study Indian ‘Glyphs’ On Ancient Monuments.” The Sun. (Baltimore, Maryland.) June 13, 1920.

[32] In late-1888 (not long after Holloway interviewed Alice Plongeon) William E. Gates made arrangements to represent the Hammond Typewriter Company in Cleveland, and act as the general agent for that company for the State of Ohio. While there, he established the Cleveland Branch T.S. The Hammond Typewriter Company, however, sold Gates out in favor of McGill & Co. (Chicago.) For the protection of his creditors, Gates made an assignment in Cleveland in late November 1888. “The amount of his depts. was between $1,500 and $2,000 mostly borrowed money to make his business profitable.” On December 10, Gates was arrested on the charge of appropriating $263 belonging to the company. While the constable was looking for Gates, a second affidavit was prepared, alleging that Gates had obtained $420 worth of typewriting machines from the Hammond Co. by “misrepresentations as to his financial responsibilities.” Judge writes: “The Hammond people, through John Mitchell, an employee, began a bitter prosecution, for some reason, only known to themselves. No less than six warrants were sworn out against [Gates] in Cleveland, charging him with crimes. [He] was arrested on a warrant charging the theft of several writers. The officer was made to produce five other warrants, which he was holding back to serve as fast as one proved ineffective. [Gates] was released on bail, and his case was championed by the Cleveland papers as against the company. When the case came up for trial, it was dismissed […] He had been [in New York] two weeks when we heard the [Hammond Typewriter Company] was taking proceedings on the ground that he was a fugitive from justice,” Judge states. “I advised his return to Cleveland forthwith and walking with him to the Pennsylvania Railroad Ferry when he was arrested [on March 25, 1889.]” Sergeant Sheldon of the Central Office had arrested Gates on a dispatch from the Chief of Police of Cleveland, who charged that Gates was wanted for the embezzlement of $2,981. “A ministerial looking young man,” Judge Duffy thought Gates was a divinity student at the arraignment in the Jefferson Market Court. Gates explained that it was an old charge “which had already been disposed of” and “was willing to go back to Cleveland without requisition.” Judge Duffy told Gates that he would have to wait the regular course of the law and committed him to jail for ten days. “[Gates] was committed, ostensibly to wait for the extradition papers, and was in jail for five days,” Judge states. “Then I got him out on a writ of habeas corpus, and Judge Lawrence dismissed the complaint.” Gates subsequently went Cleveland and was arrested on a warrant issued in Cincinnati and taken to that city. Judge went there and got a man to sign Gates’s bail bond. (This may have been around the time that Judge and Arch Keightley attended a special meeting of the Cincinnati T.S. on April 26, 1889.) At the ensuing trial, the jury acquitted Gates. [“Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III, No. 6 (September 1888): 203-204; “Local News.” The Summit County Beacon. (Akron, Ohio) December 12, 1888; “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. IV, No. 9 (December 1889): 290-294; “Jailed Till Extradited.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts.) March 26, 1889; “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. IV, No. 2 (May 1889): 59-61; “The Hammond Typewriter Company…” The American Stationer. Vol XXVI, No. 17. (October 24, 1889): 1052-1053.]

[33] “Theosophical Activities.” Lucifer. Vol. VII, No. 38 (October 15, 1890): 163-172; Le Plongeon, A.D. “The Mayas: A Lecture Delivered At The Blavatsky Lodge, Theosophical Society.” in Theosophical Siftings Vol. III (1890-91) The Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1891): 1-15.

[34] “The Theosophical Society.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) September 8, 1890.

[35] [November 24/ November 12, 1890, London, England] Johnston, Vera Vladimirovna. “From the Letters of Vera Vladimirovna Johnston (1884–1910); “Free Lending Library” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. I, No. 2. (July 1904): 69-70.

[36] [Judge, William Quan. “Cities Under Cities.” The Path. Vol. VII, No. 8 (November 1892): 259-261.]

[37] The entry has Blavatsky stating: “Let me tell you some of the things I have learned since I absented myself from the outer world. Many of the problems of life that should have been solved if we had been more together have come up before me & I have learned much. I am, next to the American work, interested in Spain. Ireland can take care of itself. In the pine woods I have found a lodge which I knew something about before I went away. There, seven chelas & the light they show that someday will be better known, I will describe to you at our next meeting. There is much connected with it that can be used for irradiating forces in this country for there is a subtle connection. Be sure that at our next meeting it is not forgotten […] Slowly the light from this Lodge is being thrown over Spain & I see that from the old corpse of bigotry superstition & credulity will be reared a temple of light which will unite its forces with that of America & Ireland & from these three points I know that humanity will be saved […] This battle of light & darkness in our midst seems but small (little) when I view the work before us […] and the ends and prospects of our work shall stem the tide of this cruel & unworthy persecution. Under all work shall stem the tide of this cruel & unworthy persecution. Under all of it & over it all the Masters hand; be sure that all is well for thee […] The light mentioned in Spain is of seven sides & a purple & yellow light. On each of the seven sides is a star. This represents the Lodge of Spain. Connect yourself with it as you will be directed.” [“E.S.T. Circular Of April 3, 1896.”]

[38] “Occult Boom.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) June 1, 1896.

[39] When describing the intention of the Theosophical Crusade, Hargrove stated: “We shall show the Europeans and Hindus that instead of America being a new country, a mere mushroom growth, as it is often supposed to be abroad, there was an immense pre-historic civilization on this continent, in Mexico, certain parts of California, Peru and elsewhere. We will further show them that the people of the time were Theosophists in their beliefs. We can prove this by means of the symbols found carved on the ancient buildings and statues that are extant at the present time, also by means of such books as the Popol Vuh of the ancient Guatemalans.” [“The Theosophist Crusade.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York,) June 12, 1896.] In Hargrove’s essay, “Progress Of Theosophy In The United States,” for the June 1896 issue of The North American Review, he writes: “The sacred books of the world tell the same story, and instead of being opposed to each other as is generally imagined, they are but different presentations of the same eternal verities. In the Chinese Tao-teh-hing, the Hindu Upanishads, the Buddhist Suttas, the Zend Avesta of the Zoroastrians, the Popol- Vuh of the ancient Guatemalans, the Christian Bible, and in such records as have been left us of the teachings of Pythagoras, Plato, Ammonius Saccas and others who had been initiated into the Sacred Mysteries, as they were rightly called, the same teachings are to be found, differing in form and phrasing, often superficially contradictory, but still the same.” [Hargrove, E. T. “Progress Of Theosophy In The United States.” The North American Review. CLXII, No. 475 (June 1896): 698–704.]

[40] Johnston writes: “Clement Griscom did much to facilitate my coming, in that kind and gentle way which was so deeply characteristic of him; and from that time forward, his friendship was among my most precious possessions.” [Johnston, Charles. “Reminiscences.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XVI, No. 4 (April 1919): 323-326.

[41] In his translation and commentary of the Chhandogya Upanishad, Charley writes: “This whole cycle is indicated in the story of King Pravahana, in a symbolic form which is at no point difficult to penetrate, if we use the clues to be found scattered through the Upanishads. The symbols belong to what has been called the Mystery Language. They appear to be exactly the same as those which are used, let us say, in the Egyptian Book Of The Dead, and in the earlier and more mystical chapters of The Popol Vuh, which is almost the only accessible record of the ancient Occult Schools of Guatemala and Central America. It may be suggested, in passing, that a part of the substance of The Popol Vuh is so ancient that it contains memories of the spiritual history and powers of the Third Race, and also of the sinking of Atlantis.” [Johnston, Charles. “Chhandogya Upanishad: Part V, Sections 3-10.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIII, No. 3 (January 1926): 219-226.]

[42] Dorsey, George Amos. The Cheyenne. Vol. II. Field Columbian Museum. Chicago, Illinois. (1905): 62.

[43] Thoburn, Joseph Bradfield. A Standard History of Oklahoma: Volume IV. American Historical Society. Chicago, Illinois. (1916): 1640.

[44] Johnston, Charles “The Sun Dance traditions Of The Southern Cheyenne.” The Southern Workman. Vol. XXXII., No. 3. (March 1903): 173-174.

[45] “What Is Going On Today.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) January 13, 1903; Watkins, Frances E. “Charles F. Lummis and the Sequoya League.” The Quarterly: Historical Society of Southern California. Vol. XXVI, No. 2/3 (June-September 1944): 99-114.

[46] The American Museum Of Natural History Annual Report Of The President For The Year 1899. The American Museum Of Natural History. New York, New York. (1900): 48.

[47] Williston, S.W. “The Fossil Man of Lansing, Kansas.” The Popular Science Monthly. Vol. LXII. (March 1903): 463-475.

[48] The American Museum Of Natural History Annual Report Of The President For The Year 1903. The American Museum Of Natural History. New York, New York. (1904): 24-25, 33, 36.

[49] Higgins, Shawn F. “The Benedick: An Analysis of Talks on Religion.” Dewey Studies. Vol. VI, No. 2. (2022): 16-75.

[50] Calvin, Samuel; Salisbury, Rollin D. “The Geologic Relations of the Human Relics of Lansing, Kansas.” The Journal of Geology. Vol. X, No. 7 (October-November 1902): 745-779.

[51] “The Lansing Skull.” The New York Tribune. (New York, New York) December 21, 1902.

[52] Johnston, Charles. “The Sun Dance Traditions Of The Southern Cheyenne.” The Southern Workman. Vol. XXXII., No. 3. (March 1903): 173-174.

[53] Griscom, Ludlow. “Changes In The Status Of Certain Birds In The New York City Region.” The Auk. Vol. XLVI, No. 1 (1929): 45-57.

[54] Abstract Of The Proceedings Of The Linnaean Society Of New York For The Year Ending March 12, 1918. No. 30 (1917-1918); Abstract Of The Proceedings Of The Linnaean Society Of New York For The Year Ending March 11, 1919. No. 31 (1918-1919); Peterson, Roger T. “In Memoriam: Ludlow Griscom.” The Auk. Vol. LXXXII, No. 4 (October 1, 1965): 598–605.

[55] “Birds Seen On Battlefield” Charlevoix County Herald (East Jordan, Michigan) December 5, 1919.

[56] Davis, William E. Dean Of The Birdwatchers: A Biography Of Ludlow Griscom. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. (1994): 27, 29, 30

[57] Johnston, Charles. “Birds Seen In New York And Long Island.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) October 28, 1923.

[58] “Notes And Comments: The Guatemalan Secret Doctrine.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XVII, No. 2 (October 1919): 113-121.

[59] Johnston, Charles. “The Two Mexicos.” The Atlantic Monthly. (November 1920.): 703-709.

[60] Lantz, Emily Emerson. “Maya Society Formed To Study Indian ‘Glyphs’ On Ancient Monuments.” The Sun. (Baltimore, Maryland.) June 13, 1920.

[61] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3767. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Percy H. Fawcett. [10/7/86]; Grann, David. The Lost City Of Z. Vintage Books. New York, New York. (2010): 196-198.

[62] Mason, Gregory. Silver Cities Of Yucatan. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York (1927): 272.

[63] Ibid, 214.

[64] “Mayan Explorers Face Jungle Peril.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 5, 1926; “Sail To Find Cities Buried In Jungle.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 10, 1926.

[65] Mason, Gregory. “Buried Maya City, With Six Temples, Found in Yucatan.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 9, 1926.

[66] Mason, Gregory. “Buried Maya City, With Six Temples, Found in Yucatan.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 9, 1926; Mason, Gregory. “Science Seeks Key To The Maya Riddle: The Mason-Spinden Expedition.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) January 17, 1926; Mason, Gregory. “Buried Maya City, With Six Temples, Found in Yucatan.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 9, 1926; Mason, Gregory. “Maya Ship Battles Sudden Gulf Gale.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) February 24, 1926; Mason, Gregory. “Finds Maya Ruins Still Being Used.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) March 2, 1926; “What Mason Found Of The Lost Mayas.” The New York Times (New York, New York) April 13, 1927; “Griscom Discovers Seven Bird Species.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 7, 1926.

[67] Mason, Gregory. Silver Cities Of Yucatan. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York (1927): 255.