Blavatsky and Olcott were entertaining Olcott’s sister, Belle, in the Lamasery.[1] Also present was Charles Sotheran, who brought with him two friends, Alice Hyneman, and Richard Harte. Hyneman was a poet, whose literary labor focused on social reform.[2] Harte was an “austere gentleman” of Irish extraction, having been born in County Limerick in 1840.[3] He was a journalist, but hypnotism, mesmerism, and “all their allied subjects,” had been the primary interest of his life since he was a youth. A restless spirit, Harte was a world traveler. In 1870 he left Ireland for Australia, where he took up large-scale sheep farming. Later he went to the South Sea Islands, eventually arriving in America in 1876. Here he lectured on the “Irish Question.” In a few months’ time, Harte would also join the Theosophical Society.[4] Sotheran and his partner, John E. Heartt, had recently acquired The New York Echo, a Masonic newspaper which they were now promoting as “The only Secret Society paper in the world.”[5] The nature of their visit was to solicit articles from Blavatsky and Olcott. Blavatsky (unenthusiastically) agreed. Her article was titled, “Ahkoond Of Swat: The Founder Of Many Mystical Secret Societies.” “In 1847-8 the Prince Mirza, uncle of the young Shah and ex-governor of a great province in Persia, appeared in Tiflis, seeking Russian protection at the hands of Prince Vorontsov, Viceroy of the Caucasus,” she writes. “Having helped himself to the crown jewels and ready money in the treasury, he had run away from the jurisdiction of his loving nephew, who was anxious to put out his eyes.”[6] Though she did not mention it in her article, Prince Mirza was the reason that her family, the Fadeevs, were evicted from their home in Tiflis, Georgia. It was when she was still Lelya. Her grandfather, Dede Andrushka was sent there to govern. So in May 1847, her grandmother, Baba Lena, her sister, Vera, brother Leonid, Antonia (their nanny,) their aunts and uncles, and a whole household of servants, left Saratov for the frontiers of the Russian Empire.

~

Their bulky three-level steamer was a merchant ship called the St. Nikolai, and as such, there were no passenger cabins. It was only with permission from the captain that they were able to occupy one of the tiny rooms near the large communal cabin. It was so cramped, that there was not even a place for everyone to sleep. Vera actually slept on the large dining table in the middle of the cabin. The concept of scenic tourism in Russia was less than a decade old and cultivated in no small part by the Tsar himself. In 1838, the Ministry of the Imperial Palace commissioned two landscape painters, the brothers Nikinor and Grigorii Chernetsov, to travel the length of the Volga River, from Rybinsk to Astrakhan, on a domestic “voyage of discovery.” The vast expanse of provincial landscapes was thought to be unappealing, and the practice of domestic travel had yet to make inroads in the Russian culture, preferring, rather, to visit Western Europe. Russians usually described their frontier as unspectacular, and monotonous.[7] And though it was true, that the closer the St. Nikolai got to Tsaritsyn, the more monotonous the terrain became, one could not deny that the mountains seemed more beautiful when sailing down the Volga.

“View Of The Volga.” Nikinor Chernetsov (1838.)

Behind the colony of Sarepta, the hills practically disappeared. Everything now looked deserted, and there was no greenery in sight. Whenever the ship stopped, even briefly, to gather firewood, or pick up cargo and new passengers, different people greeted them with well wishes, and requests to convey bows on their behalf when they next saw Dede Andrushka. In Dubovka, a town famous for its melons, some gentleman brought the children a box of sweets made from melon rinds, and in Sarepta, the colonists brought a whole box of gingerbread.

There were very heavy winds the following day, with rain that broke into a storm by nightfall. The Volga was so wide here, that the waves rolled along as if on the sea. The captain dared not venture into such black weather and dropped anchor. (The stormy waves rocked the ship with such violence, that Vera rolled off the table with considerable force.) The next day St. Nikolai arrived safely at the seaside city of Astrakhan, where they stayed for two days with some old friends of Aunt Katya (who lost her son that Easter.) She had many friends in Astrakhan, and they were treated as honored guests by several generous hosts. Having seen their safe arrival, Uncle Yuli Fedorovich said goodbye to the family and returned to his post at Saratov. Three days later the women and children boarded the military steamer Tehran to take them to Baku, as there were no passenger steamships. The most convenient route from the Caucasus to Russia was through Astrakhan and proceed to Georgia through Baku. This was the reason why so many military ships sailed along the western shores of the Caspian Sea, from the mouth of the Volga to the Persian border.

The Tehran was a much larger, and more comfortable vessel than St. Nikolai, but they had to sail on the stormy waters of the Caspian Sea. It was impossible to go on deck during the first three days, for fear of falling overboard. Lelya and the children did not suffer so much, but all the adults, especially Antonia and poor Aunt Katya, who was already in low spirits from the separation from her husband. Everyone was terribly exhausted, but fate took pity on them. The wind died down, and the rolling boil of the sea was reduced to a simmer. The horizon merged with the sea, and the sun, rising from the waves, cast an orange-purple light on the dark green surface of the sea, and danced throughout its vast distance. Further away, the dark grey Caucasus Mountains could be seen, topped with snow-white peaks.

Wrapped in Aunt Katya’s large warm scarf, Vera sat by the railing of the ship to admire the view. It was not long before she saw something that took her by surprise, frightening her even. It was a man, or perhaps a large child, with a smooth white head and very large eyes, and emerged from the sea like a rusalka, and plunged back into the water.

“What is this?” cried Vera, rushing to the first sailor who passed by. “Look! Look! Who is this jumping out of the sea? See! Look over there! There it is again! Who is that?”

“Those, young lady, are seals,” the sailor answered, smiling gently at her fright. “There are many of them here—especially at dawn. When the sun rises, they dance with joy like that.

“Living seals!” cried Vera, delighted to meet the relatives of her acquaintance from Baba Lena’s office. “So this is where they live!”

The Tehran approached the shores of the Caspian four more times before reaching Baku. The first stop was near a large ulu of Kalmyks who paddled out to the steamer in frail little boats to sell fresh fish to the mariners. The second stop was in Petrovsk, where they saw the fortress and the city when the Tehran laid anchor for several hours. Two days later they stopped in Derbent, where they rode through the mountainous, crooked streets, to examine the old fortress palace of the Derbent Khans. They also saw the “house of Peter the Great,” that is, the dugout where he lived for several days in August 1722 while waiting for the surrender of the fortress. This dugout on the seashore was now fenced in with a brick foundation, pillars, and roof. It bore an inscription that read: “The first Russian Tsar to ever penetrate beyond the Caucasus Mountains stayed here.” Many military men boarded the Tehran at Derbent, having recently returned from an expedition in the Dagestan mountains. Rumors were circulating that a Shaman in a distant part of Siberia had prophesied that Russia would fight a great Holy War in five years’ time.[8]

On May 21, 1847, they saw the silhouette of the sun-scorched mountains in the light blue sky. Huddled closer to the sea were the walls, towers, and domes of Baku, the place where, after a long separation, they reunited with Dede Andrushka.

Derbent c. 1850.[9]

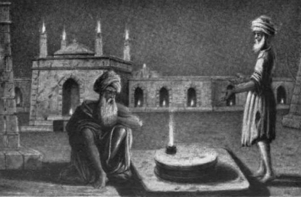

Baku, in the desolated steppes on the black, tar-soaked shores of the Caspian Sea, was known as the “city of eternal flame.” Beneath Baku, there was a huge wealth of oil reservoirs, the gas of which perpetually released through cracks in the earth. This gas ignited itself and produced an eternal fire for several centuries. This temple shined golden among the lakes and pools of amber oil that surrounded it. It was quite a spectacle, especially at night.

In places where the strongest streams of fire were found, fire worshipers built a temple to worship the god of fire. One of the strangest of these structures was the Atashgah of Baku, something of a cross between a medieval Cathedral and a fortified castle, built in unknown ages, by unknown builders. It was bounded by an ever-shining wall made from white clay. Next to it, made from the same material, were a number of cells where fire-worshipping ascetics lived. In the center of the temple complex, standing on tall pillars was a pavilion with a cone-shaped roof that was crowned with an iron trident. Tongues of ever-burning flame licked from recess in the stone floor, at the four corners and middle of the temple.

Above the entrance to the two-story gate, there were “receiving rooms” for patients who came to be treated. Many poor people from afar dragged themselves into this temple and remained there for many weeks, healing themselves with the water of the mineral well, which was located next to the “well of fire,” a volcanic crater on a perfect plane, surrounded by a thick clay wall. In the depths of this “well of fire” everything burned, shimmered, and seethed. Everything that fell into it immediately turned to ashes, and it was said that it served as a grave for fire worshipers dying in the temple.

Worshippers In The Baku Temple.[10]

Lelya, who had wandered off, stared into the red-hot crater, intoxicated by the changing colors.

“Sometimes people lose their balance and fall in,” said one of the mendicants in the temple. “The well has an attractive power for the chosen ones, and anyone who fell into it alive becomes a saint, immediately accepted into the bosom of God.”

“Which God?”

The mendicant glanced over at a mysterious figure who looked something like a Hindu fakir. The person, Lelya would learn, was a “wise man” who possessed the ability to cast spells by doing little more than breathing upon a person. If a victim had kindled the “wise man’s” wrath, they would find himself under the spell of the “evil eye.”[11]

Lelya approached the man, who whispered something in her ear.

“Lelya!” Vera cried out. “Come! We’re leaving!”[12]

~

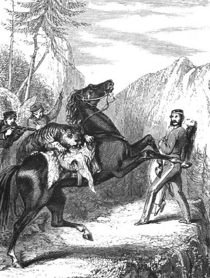

The next day they were already riding in two carriages to Shamakhi. Lelya, Vera, and Aunt Katya rode with Dede Andrushka in his carriage, and Antonia rode with the other children in a large tarantass. The convoy was guarded by numerous Chapars under the leadership of their beks (nobles,) and various police authorities. The number of Cossacks in Transcaucasia being limited, and only a few were stationed in each principal town, chiefly as an escort to the governor of the province. Their duties were performed by the Chapars, an irregular force of dashing horsemen, trained since early youth in those singular break-neck exercises for which the Cossacks of the Caucasus were so famous.[13] At several points along the route, men would rendezvous with Dede Andrushka and warn him about potential travel risks, such as raids from enemy mountaineers, and attacks of local bandits.

Feats Of Cossack Horsemanship On The Steppes.[14]

The newcomers marveled at the dexterity of their guides who wore ornate pistols and daggers tucked into their belts. What couldn’t these Chapares do? The bright red-velvet cloth of their sleeves billowed as they exchanged fire at full speed; overtaking each other, they jumped onto their saddles, and then fell over, lying down on the backs of their horses as if killed. One of the Chapares in the front of the lines threw his papakha (hat) to the ground, then another, at full gallop, picked it up from the ground and deftly tossed it back to him. These fearless riders presented a truly unbelievable exhibition of dexterity.

“They are all notorious robbers who would be all too happy to rob and stab us if they could get away with it,” laughed Dede Andrushka. “The only way to travel peacefully here is to ask the most notorious leaders of robber gangs for your convoy! All these guards are people subject to local landowners, the Tatar beks and khans. When the authorities entrust them with the protection of travelers, they themselves become responsible for their safety, and none of their comrades dare touch them for fear of being hanged.”

The admiration that Vera and Lelya felt for the galloping dexterity of their guides was diminished after my Dede Andrushka’s words. The rifles with which the Chapars jokingly exchanged fire instilled in them, now, not entirely pleasant feelings.

The first stations along the road were rather boring, as the road went through the scorched, barren expanse of the steppes. They entertained themselves with a bit of ornithology, studying the multitude of birds, and when this, too, became tedious, Dede Andrushka told them stories about the new people and places where fate had taken them.

A Tiger On The Steppes.[15]

“Lankaran tigers and leopards are found in sufficient numbers in this area,” said Dede Andrushka. “Hunting parties are sometimes arranged for these animals, which do not always end happily for the hunters. In some houses, they keep small tiger cubs, captured from killed tigresses, and keep them completely tame.”

“Aww! A little tigrenok,” fawned the girls. “Can we keep one?”

“Oh no!,” said Dede Andrushka. “These taming efforts, almost without exception, end tragically for one of the parties sooner or later. The battalion commander had a tiger cub living in his yard, at first in freedom, and when he grew up, in a cage, and he seemed completely docile. The son of the commander, a boy about eight years old, went up to the cage and began to tease the tiger with a stick. In an instant, the tiger stuck his paw between the bars of the cage, grabbed the boy’s head with his claws, and tore off his skull.”

“Oh!”

“Two versts from the city, there is a mill where they grind flour and bake bread for a military hospital. Every morning the soldier went to the mill with his sack to buy bread and bring it to the hospital. One day the soldier, having been to the mill, was returning through the forest to the city, as usual, with his sack full of grain on his back. Suddenly he saw, ten steps away from him, a large tiger standing between the trees near the road that was looking straight at him. The soldier stopped dead in his tracks. The tiger stood without moving from its place. After standing for a while, and not sure of what to do, the soldier tried to go. At the same instant, the tiger took two steps towards him, and again they both stopped. The soldier stood a few minutes and decided to move forward again—but at his first step the tiger quickly moved towards him, and they stood again, not taking their eyes off each other. The soldier was lost, not knowing what to do. but feeling the need to do something, he took one piece of bread out of his bag and threw it to the tiger. The beast grabbed the bread, then turned and ran away into the forest. The soldier, greatly frightened, returned safely to the city. The next day he calmly reached the mill—but upon returning, the tiger was already waiting for him in the same place, and the thrown bread helped him out in the same way. Since then, this story has been repeated every day for more than a year, until the authorities, having learned the reason for the decrease in the infirmary portions, made a raid in the forest and killed the poor tiger—a hunter of fresh bread.

“Then there was the Molokan who went to the bathhouse in his yard to wash, forgetting to lock the dressing room door, and a tiger suddenly appeared and rushed at him, pinning him to the ground. Fortunately, the Molokan’s wife, who was in the yard, saw the uninvited visitor enter their bathhouse. Grabbing an axe, she rushed to her husband’s rescue. With strong blows of the axe, the Molokan woman cut off the tiger’s head, laying him down in place. The Molokans, although badly wounded and bruised, remained alive. The brave Molokan woman was given a medal for saving lives.”[16]

Dede Andrushka then told them more about the Doukhobors, Molokans, as he had stayed at the Molokan Colony of Slavyanka on his way to Baku. He told them about the German Colonies of the region as well, as he had also stayed in the half-built hostelry of Iogana Vollmer, in the German colony of Elisabethtal, so named because it was founded on St. Elisabeths‘ Day (November 19) in 1818.[17]

“It is known that the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, as well as the writings of Jung-Stilling and the nonsense of Madame von Krüdener, spread the idea in Germany that the world’s imminent demise was approaching,” Dede Andrushka explained. “It is also known that Jung-Stilling and Madame von Krüdener continued to enjoy the favor and trust of Emperor Alexander Pavlovich for some time. The idea of the imminent demise of the world gave rise to and multiplied in the Germans, mainly among the common people, and aroused in them a desire to approach the place of the Holy Sepulcher, in anticipation of the time of the expected event. For the same purpose, Jung-Stilling and Madame von Krüdener asked Emperor Alexander Pavlovich for permission to initially go and settle in southern Russia.”[18]

The next day they arrived in Shamakhi. It seemed that cholera had followed them all the way to the city. Already there were reports that some of the people of Baku fell ill after their departure, and the mortality rate of that disease increased every day in Shamakhi. It was a mystery and seemed to possess the ability to advance against the wind, even traveling against the currents of an Indian monsoon. Curiously, the foreign colonies in the direct line of march of the disease were spared and remained free until the arrival of the travelers from Saratov.[19]

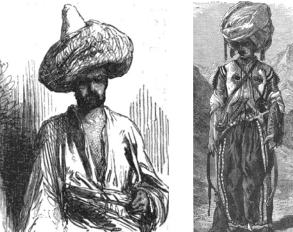

(Left) Nogai Tarter. (Right) A Cossack Of The Volga.[20]

Nevertheless, the time they spent in Shamakhi was full of joy and happiness as they had reunited with Baba Lena and Aunt Nadya, who were staying as guests of Dmitrevskys, old acquaintances of the family while Dede Andrushka conducted his official business. The family would stay with the Dmitrevskys for an additional month while Dede Andrushka continued his details. The children were excited about exploring the new surroundings of this semi-Asian city that was surrounded by mountains. They met several wealthy beks and khans of the Tatars. Their guide, a young man named Mahmud-Bek, had served in the military and had adopted some European affectations. He showed them the mosques, shops, and surrounding vineyards of the city. The gardens overflowed with wonderful roses, huge white and yellow lilies, and juicy cherries. (The cholera outbreak, however, prevented the children from berry-picking as they had wished.)[21]

They set off once more in late June, making their way to Astrakhan through Shamakhi Pass in the valley of the Akhsu River and the course of the Kura, bordered by distant mountain chains. They spent the night in the rich village of Akhsu, and the next day they crossed the Kura River by ferry to Mingachevir.

Due to the heat and the widespread rumors along the way about cholera (which was quickly spreading and intensifying in some Tatar villages,) their road was very taxing. Though the family were untouched by the disease, cholera seemed to be following them on their heels, or, more accurately, traveling with them. At every station, they asked: “Is there cholera here?” Everywhere they answered: “God has had mercy, no one has ever gotten sick.” But before they could unbridle the horses from the carriages, an alarm was invariably raised to announce that someone, be it a Cossack, a coachman, a woman, a clerk, or one of the station staff had suddenly fallen ill.

At every station they stopped, there was also much talk regarding “accidents with travelers.” The Post Office was robbed there; here they killed the guards and the coachman, and having robbed the passengers, left them half-dead without their horses. A colonel who was going to work had been shot from behind the bushes, and his family was kidnapped and taken into the mountains. Convoys were missing, and people had disappeared without a trace from the fields and vineyards. Robbers stole flocks of sheep and stabbed the poor shepherd to death. These were just the horrors that were known and reported. It was clear that although they were accompanied everywhere by a large convoy of Cossacks, it was still very often an unsettling experience. This was especially true if, due to unforeseen difficulties along the way, they reached the station at night, as no one was allowed out of the station after sunset and before sunrise. The girls learned of the arched Red Bridge over the Khram River, said to have been built by Alexander the Great. Their ears were buzzing with stories about robberies and misfortunes on this bridge. Bandits it was said, hid in the arches of the Red Bridge and attacked travelers when they drove through the middle of the structure, for there was nowhere to go when the brigands blocked the path in front and behind.

An entire day was spent in the flat city, enlivened only by vineyards and giant plane trees. The entire market square was planted with them to save the motley crowd of buyers and sellers from the scorching sun. Elisavetpol was, in appearance, neither a city nor a village, rather it was an endless orchard. The early fruits of which were typically spread in piles on the ground in the market square, but on the occasion of cholera, the bounty was diminished.

And the diversity of the population here was remarkable. Tatars with red and black sheepskin hats, some Persians with their pointed hats made of black merlushka and dashing Tatars, similar in appearance to them – the mountaineers of the eastern Caucasus, and the blue-jacketed Germans with their flat caps with huge visors. In Elisavetpol and its environs, there were many colonies inhabited by Swabians, who adhered strictly to their customs and costumes. Their clothes were adopted by the Doukhobors, who in appearance mirrored the German colonists. The Molokans, who were also present, still dressed like Russian peasants. While the main industry of the Elisavetpol colonies consisted of gardening and winemaking, the Molokans were primarily engaged in cartage and arable farming. There was not an insignificant number of soldiers and Cossacks, the latter with guns, sabers, and long pikes on their backs. They dressed according to the old model of the Donets, with trumpless caps askew. Whole detachments of the military met them now and then along the road. Hundreds of thousands of troops of all weapons were concentrated in the Caucasus, and the closer to Tiflis they got, the stronger the military (and Russian element in general) manifested itself.

Before departing Elisavetpol, they went to the mosque, and admired the tall minaret, lined with colorful tiles. From that tower the muezzin called forth the faithful at the prescribed times for prayer. They saw the madrasa, the Muslim school, in the courtyard of the Mosque where Tartar children were instructed in the ways of their faith.

They returned to the road; nerves frayed with the looming approach to the Red Bridge as the sun was setting.

“Prince Vorontsov has ordered the entrances of the arches to be blocked,” said Dede Andrushka reassuringly. “There are also Cossack pickets on both sides of the bridge.”

Baba Lena was still worried, and her fear spread a little to everyone. As they approached the bridge, a caravan of Tatars was passing across it. Sitting atop tall camels, they passed in a slow line, their black silhouettes against the background of the blazing sky. For those unaware that robbers did not travel in caravans, it was an ominous sight.

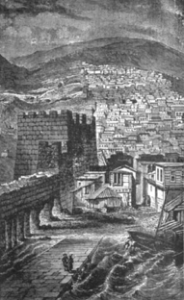

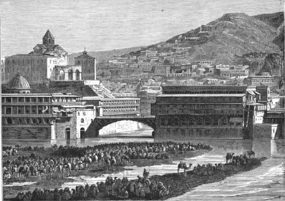

On June 15th they finally reached Tiflis, the first views of which could be seen looming above the Kura River.

“Mtatsminda, the ‘Holy Mountain,’” said Baba Lena. “Saint. David, one of the Christian educators of Georgia lived on it in a cave with a miraculous spring. There is a church there now, with a magnificent view. One of these days we will attend service there and deliver a prayer to Saint David.”

The Kura was moving fast now, compressed as it was by the rocks. There were vineyards and orchards all around, and small buildings with earthen roofs one above the other. To the right, high upon the rocks, a large stone building stood sentinel,

“The Metekhi castle fortress and prison,” Baba Lena explained. “Now we’ll enter the old Asian city itself. Once we go down from the Avlabari Mountain, there will be an Armenian bazaar and shops; then the Zion Cathedral, a very ancient, wonderful cathedral! And after that, we will go through Erivan Square, to the new Russian city. There we will find the governor’s palace and the garden about which I wrote to you, where goitered gazelles roam free. You will feed them bread, for they will eat from your hands whatever is given to them.”[22]

The following morning the family sipped coffee on a wide gallery of Dede Andrushka’s cramped apartment. In both the old city and the new European neighborhoods, most of the roofs of Tiflis were flat with earthen terraces on which one could walk and look into other people’s courtyards and streets. From the vantage of their gallery, they could see all the surrounding gardens and buildings, the slender pyramidal poplars, and the barren Sololaki Mountain, all of which seemed buried beneath verdant green vineyards.

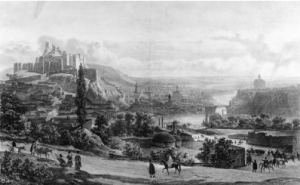

Tiflis.[23]

“What do you think about our new Asian place of residence?” asked Dede Andrushka. “It certainly surprises you and is very exciting, huh?”

“We are positively dizzy from the novelty of the impressions,” said Baba Lena.

“How could one not get dizzy!” exclaimed Dede Andrushka. “Wait, let’s go over there,” he added, waving his hand at the tops of the mountains. “Let’s go for a walk to the Botanical Garden, on the other side of Sololaki. We will climb from there to the top and return home on this side on foot. Do you see, there, the road winds from the ridge of rocks, from those ruins of towers, into our street? When you look down from there at the city or in that direction, at the garden and the Armenian cemetery, you will inevitably feel dizzy. I’ve yet to see the view from there.”

“How?” asked Vera. “Weren’t we at the mountain pass when we were driving in from Shamakhi?”

“Well, yes, it’s high there, but the mountains gradually go down, and here the cliffs are almost vertical on both sides. The Sololaki ridge is like a wall. That is why on this side, towards the city, to the north, it is completely barren. On the southern side, it is covered with the richest vegetation. There is a very beautiful Botanical Garden, and terraces that are truly something to admire.”

Prince Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov, the Governor General of Novorossiya, had initiated a flurry of reforms. Landowners, for example, were allowed to emancipate serfs if they so wished. Schools were established (even among the Khevsurs and Pshavs,) and steamboats were ordered from England with the hope of easier navigation to Sukhumi and Baku from European Russia. Tiflis also had a public library and newspapers. Princess Elizabeth Branicka Vorontsova, the wife of Prince Vorontsov, who showed no less interest in the Caucasus, would often sign documents in her husband’s name. She particularly championed the cause of female education.[24]

The family went down into the noisy, dirty quarters of the old city, and shook along the pavement past the Asian baths, through the narrow streets and alleys of the Tatar Maidan and the Armenian Bazaar. It was an assault on the senses. The babble of Georgians, Armenians, Tatars, Persians, soldiers, Europeans, children, and veiled women filled the air. The mystery of these tongues, like their cousins, was slowly being revealed. (A year earlier, in 1846, Mirza Kazem-Bek published his General Grammar Of The Turkish-Tatar Language, which provided the first use of the term “Azerbaijani language.”)[25] To this was added the cacophonous clattering of carriages, carts, wagons, and competing growling yelps of the camels, donkeys, hinnies, dogs, and rams. There were the frantic shouts of merchants and drivers, creaking unoiled wheels, the bells of camels, and, on top of all that, the screeching and drumming of the zurna—local musicians who walked in processions through the streets.

Georgian Ladies.[26]

The Armenian bazaar was divided into several sections where goods were sold and manufactured together. There was the weapons row, where along the entire length of the street, one would see nothing but daggers, sabers, pistols, cartridges, and rifles. Craftsmen in sheep’s hats on shaved heads sat cross-legged on mats on the portico of their open workshops diligently grinding bone-handles, or guiding niello onto silver scabbards. Then there was the row of hats. Everywhere one looked here, one would find colorful mountain hats, trimmed with red, black, and white braid, and trimmed with silky Angora lamb furs. Behind them were the barbers in white aprons with rolled-up sleeves hovering over lathered heads and faces. As for the culinary series, there was a lot of cooking and frying here that did not disappoint. Rice boiled in cauldrons, and juicy kebab smoked on coals. Jordanian shrak (pita bread) was piled in towers, and diners sat, legs crossed, next to the cooks preparing khachapuri, a savory cheese pie of sorts. Closer to the “Dark Row,” which connected the Maidan with the Armenian Bazaar, there was a covered arcade where all sorts of things were sold—rows of Circassian, Arkhaluk, and Bashlyk clothing. All kinds of multi-colored shoes and boots with long toes curled up, and soft Morocco slippers of all colors.

In the middle of the noisy Armenian bazaar stood the centuries-old Zion Orthodox Cathedral. Like many churches in Tiflis, it stood much below street level, and one needed to go down a rather steep stone staircase to enter. Curiously, its high bell tower did not rise near it, rather it was across the street, near a row of shops that surrounded it. One very visible reminder of Vorontsov’s changes to the character of Tiflis was the installation of the new Russian bell for Sioni Cathedral.[27] In general, church bells in Tiflis were found to be lacking in quantity and quality. This was a problem, as church peals were an important aspect of Russian Orthodox services. Different percussive intonations from variously-sized bells indicated which mass was being held; some peals, like the Dostoyno, were unique to Russia, being ordained so that those who were unable to attend mass, might, at any rate, lift up their hearts with their brethren at the sound of the bell.[28] In 1847, Vorontsov ordered a bell master from the Ural Province foundries to be sent to Tiflis and cast an 800-pound bell for the National Cathedral. The master was settled in the Tiflis German colony, on the left side of the Kura River, where he worked for several months.

Spirits were high. The family received news that Uncle Yuli Fedorovich had finally been formally transferred to service in Transcaucasia, to the office of the governor as the head of the economic departments. Dede Andrushka had feared that Count Kiselyov would be reluctant to let him move to a new post, but he did not make any obstacles.[29] Despite the troubles of moving to new quarters during the scorching heat of June, it was deemed necessary to accommodate the family. Baba Lena and Aunt Katya in particular were particularly averse to the heat, and their health was suffering. The scare of cholera did nothing to alleviate their anxiety. New rooms were secured opposite a cemetery in the neighborhood of “Vera” on the other side of the city. It was a huge, newly-completed house, beautified with semi-Asian stucco decorations, stained-glass, a round balcony, and a magnificent oval hall. A rich Armenian merchant, Prince Alexander Sumbatov (Sumbatashvili) had it built like a fortress, sparing no expense. Behind the high walls, there was a courtyard with an exquisite garden, which, though lacking adequate shading, was full of colors. As summer dilated, the days grew hot, stuffy, and dusty. Tiflis became empty, as everyone, even government agencies, schools, and gymnasiums, retired to the mountains for two to three months. Most went to the nearest regimental headquarters, from where all the military expeditions began. Dede Andrushka took the family to the waters in Borjomi.[30]

~

Borjomi Gorge was a canyon of the Kura River that was overgrown with wild impenetrable forests and surrounded by the Trialeti and Meskheti Ranges of the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. There had been fortifications here for centuries, but they fell into neglect. It was only after the Russian annexation of Georgia that attention to the region was renewed when the area was placed under the Russian military authorities. By 1810 the appellation of Borjomi was used, and by 1820 the outpost began receiving soldiers. Buildings and baths were erected in the 1830s. In the 1840s Yevgeny Golovin (Russian Viceroy of the Caucasus) took his daughter to Borjomi to partake of the cure. Subsequent to this, Golovin expedited the transfer of the waters from the military to civil authorities. It was yet little more than a shanty town, with two or three log houses nestled together, and rickety wooden gallery for the few who used the healing mineral waters. The visitors were primarily military officials, wounded or sick officers, and soldiers. For the latter, there was a small barracks near a stretch of the Kura which the Russians called the “Black River.” Across from the barrack, near the baths, was a single, spacious, government-owned house built by Golovin which the Fadeyev family occupied.

The whole family was worried about the convoy of their servants and feared for their safety owing to the many real dangers on the frontier. Among the servants, there was not a single person who was born outside the Fadeev household. Most of the young people were godchildren. Baba Lena and Dede Andrushka had been the comrades of the children since birth. The Fadeevs sympathized with their sorrows and rejoiced in their joys, and the servants, likewise, shared the sorrows of the Fadeevs and rejoiced in their triumphs as if they were their own.[31]

Their home at Borjomi was visited by pleasant interlocutors. The first was Alexander Fedorovich Witte, who met them when they arrived there. The brother of Uncle Yuliy Fedorovich, he was a captain of the railways who had served in the local army of Kutaisi for many years. He married a Georgian woman from Imereti. The second visitor was a smart, funny young field engineer named Beckman. The third visitor was an artillery officer named Kuzovlev, the son of old and dear acquaintances of the Fadeyevs. His older sister was married to the police chief of Ekaterinoslav, and his second sister was a lecturer to Ann Pavlovna, the Queen of Holland. All three of them, good people, spent their days with the Fadeyevs, accompanying them on walks and introducing them to the surrounding area.

Of the native visitors, the most prominent was the family of the local landowner, Prince Sumbatov, whose estate the Fadeyevs rented. Sumbatov himself was a retired military man, not yet old, but still a rather gloomy individual. His wife Sofia, born Princess of Mukhrani, was a middle-aged beauty who wore a heavy suit. They had two of their sons with them, one was a cadet about twenty years old, the other was a little boy no older than nine years of age. The younger brother, handsome and smart, was dressed from head to toe in white. The Sumbatovs explained that it was a tradition in those parts, when children were born, to make a promise to the Virgin Mary (or some other saint,) to clothe the child in no other color than white until puberty, believing this to attract patronage from above. In this case, the white suit failed to bestow well-being to the boy, nor did it protect him from death. Shortly after the Sumbatovs returned to their village near Surami, they were killed in their house at night by their own peasants. Sumbatov, Sofia, and six of their ten children were brutalized in a ghastly manner. An investigation found that Sumbatov had mistreated the peasants and forced them to work on holidays. Some indignant peasants refused to obey and to punish the guilty, Sumbatov ordered their wives to be re-litigated. That was the catalyst for the general massacre of the family.[32]

Just as before, cholera followed the family. The mountainous climate, fortunately, was conducive to the development of the disease, and the outbreak was of a weak degree. One victim was an eight-year-old boy, the son of a soldier. The doctor who was usually installed there for the summer season, had not yet arrived, and there was no one to help the child. The mother of the boy, seeing that her son was pale-blue and experiencing convulsions, ran out into the street and picked a crappie growing near the fence. The idea, she would later admit, came to her from some mysterious inspiration. She firmly rubbed the boy’s cold body with it, and soon enough her son was covered in red spots, blisters, and the appearance of warmth returned. Her improvised treatment was crowned with complete success. Another victim was the cook, but he too recovered without any medical intervention.

When Dr. Ambrov finally arrived, he ordered Baba Lena to bathe in the hot mineral springs of Abastumani, about fifty miles from Borjomi near the Turkish border. Lelya, Vera, Aunt Katya, and Baba Lena went to the new springs on July 16, while Dede Andrushka and the rest of the family remained in Borjomi. Along the way, they stopped in the ancient city of Akhaltsikhe for a day. All the men wore turbans and fezzes, and the women were veiled in colorful muslin. The girls thought that the town was inhabited entirely by Turks, but it turned out that the residents were Orthodox Georgians and Armenians, and only adopted the Turkish dress to avoid persecution. Baba Lena and Aunt Katya purchased very fine filigree work from local artisans, like silver bracelets, cufflinks, and brooches. There was an array of unique items, like ostrich eggs and carved coconuts, and tiny colorful cups on silver stands from which the Turks drank their strong black coffee. There were long painted inkwells, and many tiny bottles of rose oil, so fragrant that one drop was enough to perfume an entire room for several days. They also bought a whole many rosaries made of amber, bone, and coral. Armenian and Georgian women often wore them on their arms up to the elbows, and the more affluent among them, having nothing else to do, habitually fingered their prayer beads while chewing keva (white resin.)

The sulfur mineral waters in Abastumani were so hot that few people could bear their high temperature. One spring was especially hot. It was said that an Armenian bishop was once boiled to death in it. The sick were therefore ordered to bathe in the less hot “snake spring.” Baba Lena had grown weak from the hot daily baths. One day after breakfast she went out for her daily walk when she suddenly felt dizzy. Without having time to sit down or grab onto anything, she fell down a rather steep path and broke her left arm above the elbow.[33] Aunt Katya sent to Akhaltsykh for a doctor, but he did not fully appreciate the seriousness of the injury and insisted that it was only a dislocation. After practically torturing Baba Lena with his treatment, the doctor realized the arm was indeed broken and bandaged the fracture, putting the whole arm in splints. The pain eventually diminished, but poor Aunt Katya could not calm down, especially since Baba Lena refused to allow her to write to Dede Andrushka in Borjomi, and “unnecessarily” trouble him.

Dede Andrushka eventually arrived in Abastumani with Alexander Fedorovich, but he soon fell so ill that he had to be carried to the springs on a stretcher. Fortunately the “snake spring” actually helped, and Dede Andrushka recovered. Spirits were elevated even more when Uncle Yuliy Fedorovich arrived, having successfully escaped the cholera outbreak which devastated all of Saratov, and killed many of their good friends. The pharmacies did not have time to prepare medicines, and they were literally besieged by crowds of people who waited in turn, sometimes for days, to receive medicine. For many, this was time they did not have. Entire families died out, and many houses were filled with corpses.

At the end of August, they all moved back to Tiflis together where a joyful reunion awaited the family. All of their people, the adjutants and servants had finally made the long journey from Saratov. It was a true joy and great entertainment for everyone. The whole family, with Baba Lena at the head, inquired about their journey. Baba Kapka, Mavra (the wife of the butler Yakov,) and the senior maids vied with each other to tell Baba Lena and Aunt Katya about their impressions, fears, and troubles during their three-month wandering through the steppes and mountains. Yakov, Peter, the third cook Mikhailo, and the coachman Ivan, handed over reports to Dede Andrushka. The younger generation, Sanya, Dunyasha, Dasha, and her younger sister Lyuba, chatted endlessly with Lelya and Vera, finding in them sympathetic and interested listeners. Leonid joined the boys, Nikolka, Volodya, and others, and ran to the stables to inspect the draft horses “Arabchik,” “Tonkoy,” and “Tolstoy,” whom they had not seen for a long time, and whose condition they were most interested in.

There was only one family who neighbored the Sumbatov house. They had three daughters, the eldest being five years younger than Vera, and a son, Tsutsa (nickname for Stepan,) who was the same age as Leonid. The boys became fast friends and played together in the garden and the huge yard. Tsutsa spoke Russian very poorly, and Leonid kept making him laugh for this, as well as ribbing him for his name (which really would have been more of a decent nickname for a small dog than a boy.) Antonia, Vera, Leonid, and little Sasha were placed on the mezzanine upstairs. Antonia continued to teach the children, but she began to get sick again, which saddened Vera to no end in those large low rooms with wide windows.[34]

~

Winter was unusually long and unexpectedly cold. The first snow fell at the end of November and continued (with intervals of thaw) until the middle of January. Tiflis seemed noisier and livelier. All the streets, especially in the Old City, were lined with rows of open shops that sold Russian, Turkish, and Persian sweets, that is, dried and fresh fruits, all kinds of nuts, and whole tubs of honey.

“Koku!” “Zapakh!” ”Suni!” they shouted, interrupting, and drowning each other out with these exclamations. “Smell!” “Here! Here! I have some fruit!” “Gulab! Figs! Cherry plum! Komshi! All kinds of fruit, dried, boiled, fresh, sweet as myod! (honey!)” Another merchant yelled even louder using the full width of his throat. “Groin! Groin! Groin! Myod, myod, myod! Beliy! Clean! Sweet! Guzinok! Persian kamfet! Master! Here! Here!”

At night these shops were illuminated by multi-colored glass lanterns, and tallow candles wrapped in paper and stuck right into the tops of the sweets. Crowds of improvised musicians moved rhythmically along the streets and squares. The zurna, inflating their bellows, filled the air with the shrill groans, squeaking, squealing, and grinding of their amazing instruments, while the hypnotic beating of drums, reverberated throughout the city. Boys ran behind them, jumping and making faces in colorful rags. They wore painted paper-masks, and pointed hats wrapped in colorful rosaries and gold paper.

Prince Vladimir Sergeevich Golitsyn.

In general, life was interesting for the whole Fadeyev family, and there were a lot of people in their hospitable house. This was a great pleasure for Lelya, who loved society very much, in contrast to Aunt Nadya, who did not care for such gatherings and especially loathed going out to galas and balls. Although Vera had no time to be bored, she often missed her friends in Saratov. She (almost) never went to the living room in the evenings, preferring, rather, to sit upstairs and study, read, or drink tea with Antonia when her health allowed. Antonia now worked with Leonid every day and continued to sew for all of the children.

Old friends often called on the family, such as Prince Vladimir Sergeevich Golitsyn, the maternal cousin of Princess Elizabeth Branicka Vorontsova. Dede Andrushka first met Prince Golitsyn thirty years earlier in Penza, when he was a stately, handsome young man who led the dashing life of a hussar (and captivated all the ladies of the city.) He was more rotund now, and the southern heat made him move like honey, but his temperament remained unchanged. He was cheerful, good-natured, witty, inexhaustibly amiable, and quite fond of singing funny couplets.

“Vladimir Sergeevich reminds me very much of Zakrevsky,” Vera told Lelya.

“Zakrevsky is as similar to Golitsyn, as a fat bulldog is to a lion,” laughed Lelya.

The Sons Of General Alexei Ermolov.

Prince Golitsyn had two sons, but the eldest, (and more handsome,) Alexander Vladimirovich, visited their home more often. The sons of Alexei Petrovitch Ermolov, the famous Caucasian Commander-In-Chief, were also frequent visitors, especially Viktor Alekseevich, born in Dagestan in 1821 to General Ermolov’s cabin wife Syuda.[35]

One day at lunch, Vera asked Viktor what the gold letters “C” and “G” (“Caucasian Grenadier”) meant on his epaulettes.

“Oh,” he replied. “It means ‘crazy goose!’”

“What a pity!” said Vera, in a tone of condolences. “I thought you were a human!”

Everyone began to laugh. Viktor, pretending to be very embarrassed, covered his eyes with his hands. “Ah! What a cruel young lady! How she embarrassed me!”

“Oh! She’s angry with us! She won’t even allow you to joke around,” said one of Viktor’s companions. “You’d better tell her what the “C” and “G” really mean.”

“You will just choose more such nonsense words!” said Vera. “I don’t particularly want to solve this riddle, so it’s better not to bother inventing it.”

“How formidable!” Lelya cried.

“Exactly!” said Viktor, cheerfully picking Vera up. “How formidable indeed!” He leaned towards Lelya in the other direction. “Thank you for not coming up with more offensive words!”

Subsequently, Ermolov and Vera became friends, and she confessed to him that it took a lot of effort for her to contain her annoyance. Viktor, likewise, told Lelya strange tales regarding his father. When General Ermolov was still a young Lieutenant-Colonel he was visited by a strange apparition that instructed him to write down the date and time of his own death: “11:30 a.m. April 23, 1861.”[36]

On New Year’s Eve, the family attended a Gala hosted by Prince Vorontsov. It was the first time that Lelya wore her first big ball gown, and even Vera admitted that she looked beautiful. The men, meanwhile, discussed civil matters, and the outlook of the frontier. Vorontsov was optimistic of victory in Dagestan in the coming year. “One can say that Greater Chechnya is in our hands,” Vorontsov told Ermolov, “and without it Greater Chechnya will not resist long.”[37]

Prince Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov.

The bell for Sion Cathedral was now completed, and days after Vorontsov’s New Year’s Ball, it was prepared for transportation to Tiflis. The cold had intensified, and snow covered all the streets. The locals were very surprised and said that they could not recall such a harsh winter in the region. The bell was supposed to cross over a temporary wooden bridge over the Kura, and on the appointed day, many people gathered there to witness its transportation.

According to an ancient Russian custom, Orthodox people transported bells to their church at their own expense. This had not been an issue in the past, since there was never any bell in that area that could not be carried by a single man, and locals had no understanding of this tradition. The bell, therefore, was transported by a company of soldiers. The bell was installed on a large, iron sled, and harnessed to the soldiers with long ropes, several in a row, and in a long line. Vorontsov rode on horseback at the front, accompanied by a large retinue. Just as the solemn ceremony was about to begin, and the soldier prepared to move forward, the foundry master who cast the bell interrupted.

The old bearded Russian approached Vorontsov and bowed low, expressing that he could not say “What do you need?” asked Vorontsov.

“Your Majesty,” said the foundry master, “order to find out whether there are any Jews among the soldiers who are transporting the bell. If there are, remove them from this task.”

“Why is that?” asked Vorontsov with surprise.

“Your Excellency, this is my craft,” the old man replied. “I have cast a lot of bells in my life. I have seen how they are transported. I humbly ask that if there are Jews here, tell them to leave, otherwise they will inevitably be killed. How many times have I heard from others, and myself been witness to misfortune.”

Vorontsov nodded his head slightly and, with a condescending, half-contemptuous smile, hurriedly said: “Good, good, my dear fellow.” He then turned the horse and rode off. “Let’s get moving!” he commanded.

Tiflis c. 1840s.

The soldiers transported the bell safely across the bridge and stopped in front of a small hill to catch their breath. They rested cheerfully, unaware that the sleigh with the bell was resting on a dangerous pool of ice. Returning to work, they strenuously pulled the ropes to move the sled out of place. A piercing scream stopped them dead in their tracks. A soldier, harnessed in the first row nearest the sled, had slipped on the ice and fell. The eight-hundred-pound bell slid off the sleigh and slid across the soldier’s body from the right leg to the left shoulder, cutting him like a razor. Blood gushing out of the forked body presented a gruesome scene. Some soldiers were dispatched to retrieve the salvageable parts of the corpse, while other soldiers scraped up their fallen comrade’s entrails with shovels. These were placed on boards and carried away, the intestines, falling from the boards, dragged along the ground.

Princess Vorontsova felt ill, and a glass of water was brought to her from a neighboring house. He then called the commandant, the old General Briesemann von Nettig. “Go now to the exarch (bishop,) tell him about this incident. Tell him that I request of him that this soldier—a man who died in a godly act while transporting a bell to the cathedral—be buried in a place of honor at Sion Cathedral. Tell him that he will greatly oblige me with this.”

The commandant rode off to carry out his duties, but after a few minutes, he returned.

“Your Excellency,” he told Vorontsov, “this man cannot be buried in the Elephant Cathedral.”

“Impossible,” said Vorontsov. “Why not?”

“He’s a Jew,” the commandant replied.

Vorontsov was embarrassed. The event puzzled him to no end.

Though he did not say a word, he could not help but remember the request and prediction he had heard from the old foundry master.

The blood-stained snow at the flood bridge was seen for several days after the incident.[38]

~

While staying in Tiflis, Lelya encountered another fire-temple, the Atashgah of Tiflis. It was not like the one that she saw in Baku. “Few persons are capable of appreciating the truly beautiful and esthetic,” Lelya thought, “fewer still of revering those monumental relics of bygone ages, which prove that even in the remotest epochs mankind worshipped a Supreme Power, and people were moved to express their abstract conceptions in works.”[39]

Faravahar.[40]

The Englishman, Sir Austen Henry Layard, had recently discovered the lost Assyrian city of Nineveh. In the reports of his findings, published in 1849, Layard said there were many strange tales connected with the ruins. Layard found a temple of which “all manner of sculptured figures” featured on the walls, and were “covered with inscriptions in an unknown language.” The locals told him the former temple once housed a black stone held in great reverence by the Yazidis, or “worshippers of the devil.” These same ruins also contained symbols of a deity, “the figure with the wings and tail of a bird enclosed in a circle,” which resembled the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda.[41]

“With the destruction of Nineveh, the world has been for many centuries without the necessary data upon which to estimate the real knowledge, esoteric and exoteric, of the ancients,” Lelya thought. But, within the past few years, the discovery of the Rosetta stone, Anastasi, and other papyri, had opened a field of archaeological research that was likely to lead to radical changes in this “firm and unalterable experience.”[42] She considered for a moment her encounter with the mystic in Baku, and of her own visions of Master Morya. Scattered throughout the world there was a handful of thoughtful and solitary students, who passed their lives in obscurity, far from the rumors of the world, who studied the great problems facing the physical and spiritual universes. Their secret records of the long lines of recluses were preserved by their successors, and Lelya was determined to seek them out, one way or another. To gather the knowledge of their early ancestors, the sages of India, Babylonia, Nineveh, and the imperial Thebes.[43]

She set to work researching the Ashtagash of Baku. With the exception of some old Armenian Chronicles that mentioned it in passing as having existed before Saint Nina brought Christianity to the region in the Third Century, there seemed no other mention of it. Yet, until 1840, the Atashgah of Baku was the chief rendezvous for all the Persian Zoroastrians, known contemptuously as “Gabr” by the Muslims and Christians, alike. Thousands of came here, for “no true ‘Gabr’” could die happy until they performed this sacred pilgrimage at least once in their lifetime.

Tradition said that long before the Persian Prophet Zarathustra, the people of that region recognized Mithra, the Mediator, as their sole and highest God. For countless ages, the devotees of Mithra worshipped at his shrines, until Zarathustra descended from heaven in the shape of a “Golden Star,” and transformed himself into a man so that he might teach a new doctrine of the “One but Triple God.” The supreme Eternal, Zurvan, transcendent and neutral, emanated equal but opposite twins, Ahura-Mazda and Angra Mainyu, thus creating duality in nature. To do this, Zurvan had to absorb all the light from the fiery Mithra, thus leaving the poor god despoiled of all his brightness. Mithra, in despair, annihilated himself but promised his faithful devotees that he would return one day. But then a series of calamities fell upon the “Fire-worshippers,” the last of which being the Muslim invasion of Persia in the 7th century. Driven away from every quarter, some Zoroastrians found refuge in the city of Yazd. Then followed heresies. Many of the Zoroastrians abandoning the faith of their forefathers, became Muslims; others in their hatred for the new rulers, joined the mountainous tribes Kurds who dwelled in the eastern portion of Turkey and Persia since time immemorial. There was a debate among ethnologists as to whether these people were “Aryan” or “Semitic,” but Lelya believed that they were of Indo-European origin. Nominally, Muslims (of the sect of Omar,) their rites and doctrines were purely magical. Despite their brigand-like disposition, they united in the mysticism of the Hindus with the practices of the Assyro-Chaldean magicians, vast portions of whose territory was under their control, and would not forfeit to either Turkey or Europe. The Zoroastrians who found refuge with the Kurds blended their traditions, creating the Yazidis whom Layard mentioned.[44]

~

In 1847 Bahman Mirza, the ex-governor of Azerbaijan, and uncle of the young Shah, Naser al-Din, rushed to the Russian envoy in Tehran, asking for the protection of the Russian Tsar. Asylum was granted, as Russia believed that sheltering the Persian prince was crucial for the success of their foreign policy in Iran. Evidently, the great dervish, and rebel leader, Akhūnd of Swāt, had appeared to Bahman Mirza three times as a vision in his dreams, urging him to steal the crown jewels and ready money in the Persian treasury, and share the treasure with the protectors of the faith of his principal wife, a native of Kabul.[45]

Bahman Mirza.

At the time Prince Dmitry Ivanovich Dolgoruky, a cousin of Elena Pavlovna, was the envoy in Persia.[46] He managed to hide Bahman Mirza, and quietly escort him to the border. Stories would circulate, that Dmitry Ivanovich worked as a translator at the Russian embassy in Persia in the 1830s with a secret mission. It was said that he converted to Islam and studied under a certain Hakim Ahmad Gilani. Disguised as a Muslim cleric, Dmitry Ivanovich operated a spy network that included the future founder of the Baháʼí religion, Mirza Husayn Ali. After returning to Russia, Dmitry Ivanovich (under the alias Isa Lankarani) traveled to Iraq to visit the Atabat Aliyat (the cities where the shrines of six Shia Imams were located) where he convinced a young seminary student from Shiraz to return to Persia and launch the Baháʼí movement. Dmitry Ivanovich then returned to Persia himself as the Russian ambassador and worked to initiate the Baháʼí religion by giving instructions to Mirza Husayn Ali. The goal, it was said, was to destroy the national unity that Islam had created among Persians to serve the interests of Russia.[47] Whatever the reasoning, Dmitry Ivanovich then persuaded the Shah—at the request of Tsar Nicholas I—to send Bahman Mirza’s twelve wives, and his entire family, to Georgia. Bahman Mirza soon arrived in Tiflis in 1848 with a huge retinue of his entourage, but there was nowhere in the entire city large enough to accommodate them, so Prince Vorontzov (Viceroy of the Caucasus) instructed Dede Andrushka to give up Sumbatov’s house.

The Vorontzovs, and indeed, all of Tiflis “high society” treated these Persian immigrants with extreme deference. Feasts were given in their honor, and special pavilions were built to accommodate the wives of Bahman Mirza so they might be hidden from the gaze of the profane world while admiring dancing, fireworks, and other wonders they had never seen before. These wives, as well as the daughters of Bahman Mirza, were kept “locked up under seven locks and twelve veils,” and no one dared to steal a glance at them.

The Hahn sisters found the sight of these wives when taken to the baths both humorous and unfortunate. The women were sealed into wooden boxes, with tightly locked doors with a tiny window on top. These boxes were then attached to an elongated cart without a body called a drozhin (the front and rear parts of which were connected by longitudinal bars,) that was harnessed to two donkeys, one in front and the other in the rear. These donkeys were driven by four Persian servants, two foot and two mounted, in such a procession that people on the streets of Tiflis could not help but find comedy in the display. Bahman Mirza dressed his little sons in the uniforms of Russian Generals, and affixed to them badges, and medals, from countries all over the world. The people soon mocked these oddities, especially Bahman Mirza’s stinginess. Many jokes were told at his expense, like how he forced his wives to perform the duties of laundresses, cooks, and floor-scrubbers, so as not to hire female workers.

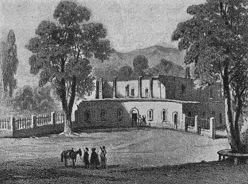

Tsinandali in the 1850s.

Dede Andrushka rented a house in Tsinandali, the former home of the Georgian politician-poet, Prince Alexandre Chavchavadze, the “father of Georgian Romanticism” (who died a year earlier.)[48] The estate, with its outbuildings, occupied almost an entire block in the very center of the new city, and Lelya and the family felt much better in their new premises than in Sumbatov’s country castle. The roofs of all the buildings faced four streets and were connected to their huge gallery by bridges and stairs, so they could take excellent walks without ever leaving the house. In the middle of the courtyard, there was a garden with a swimming pool and many roses. The house had a huge two-light hall and mirrored windows, which, at that time was a great rarity, especially beyond the Caucasus. Instead of traditional wallpaper, the walls of the living room were covered with paintings depicting mythological scenes and faraway lands. The first winter there was very lively, and animated for everyone, especially for Lelya, who was having quite a lot of fun. Only Vera, it seemed, still grieved over Antonia, who was still suffering, so she made it a point to spend extra time with her.

It was during this winter that Lelya met Nikifor Vladimirovich Blavatsky, the soon-to-be Vice Governor of Erivan, a Province that the Russians held since 1828, and which separated from the Tiflis Province in 1849 as its own Governorate.[49]

He stole glances at Lelya on occasion while discussing civil matters with her grandfather on the other side of the room. His valet, Pétré Loladzé, as always, standing at hand.[50]

“He’s a plumeless raven,” laughed Lelya.

“Nikifor Vladimirovich?” asked Miss Jeffers (her English teacher.)

“Yes.”

“Not even Nikifor Vladimirovich, this man you laugh at and call ugly, would marry you.”

Lelya accepted Jeffries’s wager with a mischievous smile, and walked across the room to over to Nikifor, glancing back at Jeffries in triumph as the Vice Governor carried on about his administrative details. Nikifor then mentioned something that actually interested Lelya. Evidently Nikifor had recently hosted the French Archaeologist, Marie-Félicité Brosset, who came to Erivan to investigate the mysterious antiquities of the land.

Nikifor Vladimirovich Blavatsky.

Not long after, Nikifor Vladimirovich, a man twice the age of seventeen-year-old Lelya, asked for her hand in marriage. Lelya agreed.

“You make a great mistake in marrying me. You know perfectly well that you are old enough to be my grandfather,” Lelya warned Nikifor. “You will make somebody unhappy, but it won’t be me.” She continued, mutinously “As for me, I’m not afraid of you, but I warn you that it is not you that will gain anything from our union.”[51]

Vera Petrovna was astonished.

“I am doing it to be free from the control of our relatives,” Lelya told her.[52] In more intimate moments she would confess that while all the young men laughed at “magical superstitions,” Blavatsky believed in them. He had so often talked to her about the “sorcerers of Erivan,” of the “mysterious sciences of the Kurds and the Persians,” that she took him in order to “use him as a latch-key to the latter.”[53] The Government of Erivan was always known for the wealth of its monuments and relics of antiquity, and that was a topic of particular interest to Lelya.[54]

~

The wedding was to be held that summer, on July 7, 1849. For the sake of proximity to Erivan, Lelya’s family went that summer to the town of Gerger. The place was immortalized by Pushkin two decades earlier, as it was here where he encountered the body of the young Russian emissary to Persia, Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov, as it was being taken to Tiflis.[55] It was a very beautiful setting, under the huge Mount Bazarduzu, the highest peak of the Greater Caucasus, the top of which one could see the top of Mount Ararat, and Small, the huge Lake Gokcha lying on a very high plateau near Erivan.

Kurdish Warriors.[56]

Vera went there ahead with Dede Andrushka, Antonia, Aunt Nadya, and Uncle Rostya, because Tiflis had already turned into a hot furnace in May. Baba Lena and Lelya left two weeks later. With them were Aunt Katya and Uncle Yuli Fedorovich, a man whom she married in 1844. They brought along their three boys, two-year-old Alexander, one-year-old Boris, and the infant Sergei.[57] Joining them was Michalko Guegidze, their Georgian servant, dressed in the traditional Georgian jacket with loose sleeves, a white fez with tassel, and a string of amber beads upon his arms that was a custom among the Georgian peasants.[58]

They were warmly greeted in Gerger by Colonel Voropaev, commander of the artillery battery located there, and an acquaintance of Andrei Mikhailovich. They settled down in a fairly large house with vegetable patches and a garden, which to Vera seemed like paradise compared to the heat and dust of Tiflis. The day after she arrived, she went on reconnaissance to collect a sheaf of various flowers, to add to her grandmother (whose Caucasian collection was greatly enriched in Gerger.)

Soon Nikifor Vladimirovich and a convoy of twenty Kurdish riders arrived wearing high, white turbans. They sat on their lean horses, inconspicuous in appearance, but strong, and fast as a whirlwind. Their red jackets were embroidered with silk and gold and belted with wide-colored sashes. Their shoes with long, upturned ends made of green or yellow morocco, stuck out from under the folds of wide shalwars. They were armed from head to toe with rifles, daggers, scimitars, and, on their backs, very long spears that were decorated at the ends with a huge bouquet of black ostrich feathers. The men smiled at Lelya with their energetic faces, beardless except for their long curly mustaches. Beneath their thick brows were lively, sparkling eyes. Having learned about the marriage of their boss leader, these Kurdish warriors expressed their desire to salute his future khanum (wife,) and came with him to meet her. Most of the Kurds from Erivan were Yazidis, and Lelya was naturally very curious.[59]

As there was no church in Gerger, the wedding party had to travel twenty miles to Kamenka.

“O holy God,” said the priest, “who didst create man out of the dust, and didst fashion his wife out of his rib, and didst yoke her unto him as a helpmeet; for it seemed good to thy majesty that man should not be alone upon the earth: Do thou, the same Lord, stretch out now also thy hand from thy holy dwelling-place, and conjoin this thy servant, Nikifor Vladimirovich, and this thy handmaid, Helena Petrovna; for by thee is the husband united unto the wife. Unite them in one mind: wed them into one flesh, granting unto them of the fruit of the body and the procreation of fair children. For thine is the majesty, and thine are the kingdom and the power and the glory, of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now, and ever, and unto ages of ages.”

Lelya’s face flushed angrily.

The priest took one of the wedding crowns and placed it on Nikifor’s head. “The servant of God, Nikifor Vladimirovich, is crowned unto the servant of God, Helena Petrovna.” In like manner he crowned Lelya. “The servant of God, Helena Petrovna, is crowned unto the servant of God, Nikifor Vladimirovich.”

The priest then made another exhortation to the newly married pair.

“O Lord our God, who hast blessed the crown of the year, and permittest these crowns to be laid upon those who are united to one another by the law of marriage, and thus grantest unto them, as it were a reward of chastity; for they are pure who are united in the marriage which thou hast made lawful: Do thou bless also in the removal of these crowns those who have been united to one another, and preserve their union indissoluble; that they may evermore give thanks unto thine all-holy Name, of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now, and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen.”[60]

“Surely I shall not,” Lelya whispered through her gritted teeth.[61]

That same day, after lunch, the young couple left for Darachichag, the “Valley of Flowers,” the mountainous retreat where every employee of Erivan lived in the summer months. They rode on horseback to Mount Bezobdal, which separated Georgia from Armenia, along a road that twisted steeply. The original convoy was joined by many at the wedding. Colonel Voropaev, Uncle Rostislav, Aunt Nadya, and Leonid on Dede Andrushka’s gentle red bacha (pacer) went to see them off. Vera would have gone too, but her leg hurt badly, so she stood sadly on the balcony and looked at the retreating riders. They were visible for a long time on the endless turns of the bare mountain. When they reached the first ledge, everyone stopped, and Lelya waved her handkerchief to her family. The Kurds, likewise, raised their shaggy pikes in farewell, and some fired their guns.

Vera cried bitterly. This was her first separation from Lelya.[62]

~

After their unconsummated honeymoon in Darachichag, Lelya moved her things into Nikifor’s home in Erivan, at the base of Mount Ararat, where she took daily equestrian excursions. It was this same Mount Ararat (if legends were to be believed) where Noah’s Ark first landed after the flood. Erivan even boasted of having to tomb of Noah. Another legend connected Noah with the name Erivan itself. It was said that this was the first spot of dry land that Noah saw when the Ark arrived on Mount Ararat. “It is visible!” shouted Noah, which, in Armenian translated to “Erivan!”[63] Safar Ali Bek Ibrahim Bek Ogli, the strongest and bravest of the Kurds, was detailed as her personal escort, and he delighted to display his unusual skill as a cavalier (and on occasion save her life.)[64] The riding style of the Kurds was a sight to behold. They somehow rode hunched over, with their legs tucked beneath them, in wide shalwars.[65]

Erivan and Mount Ararat.[66]

Developing a friendship with the Kurds, Lelya learned more about the beliefs of Yazidis. They held that the God who created all things and permeated all things, created seven spirits by a kind of emanation “as a man lighteth one lamp from another,” each of which were to reign ten thousand years. Of these seven spirits, Tawûsî Melek, the “Angel Peacock,” was the first, and present ruler of the world, having fulfilled already six thousand years of his reign. The seven Yazidi spirits seemed to be connected with the heavenly bodies, as the sun and moon also had a large place in their religious system. As for the number seven, it held a no less prominent place in the Yazidi religion than in the Chaldean, Hebrew, and Sabean systems. The seven altars of Balaam, the seven offerings made to ratify a covenant, the seven lamps of the golden candlestick in the temple, the seven angels and their seven trumpets, all suggested themselves in the Hebrew Bible, and Chaldean texts, analogs of an ancient faith.[67]

There were other stories, enchanting local legends, perhaps. There was a spot, Lelya learned, on the Araxes Mountain, of which Mount Ararat formed a part, that was called “Serpent Mountain.” During certain seasons, the serpents on this mountain multiplied to such an extent that neither man nor beast dared approach it. The story was stranger than that, however, for the law of existence for these snakes was supernatural, for if they reached the age of twenty-five without being seen by mortal eyes, it became a dragon. Not just any dragon, a dragon with the power to change its head into that of any mortal creature, to beguile its unsuspecting victims. There was once a young herdsman, it was said, who met a beautiful young lady on a path in this mountain, lamenting that she had lost her way. The herdsman immediately offered to relieve her and took her upon his horse. They had not ridden far when he fell in love with her. She confessed that she had made up the story of her having lost her way to beguile him, they were married in haste.

Bridge At Erivan.[68]

One day an Indian fakir stopped at their house, wearing an onyx ring that, as everyone knows, changed color in the presence of a transformed person. The fakir immediately sensed that something was wrong. He called the husband aside and bade him to order his wife to cook a particular dish.

“While she is cooking,” said the fakir, “slip some salt into the dish, conceal all the water have in the house, fasten the doors, and lie hid to watch her.”

The husband obeyed, and he soon noticed his wife looking for water. Finding none, she lengthened her neck to such a degree that stretched out of the chimney, and the husband soon perceived, by the gurgling sounds he heard, that she was drinking at a nearby stream.

The poor man then knew for a certainty he had married a serpent. In his despair, he consulted the fakir, who told him that the only to get rid of her was to burn her to death. He accordingly watched until she stooped to look in the oven where she was baking bread—then, suddenly seizing her by the legs, he threw in and shut the door. The woman-serpent begged piteously to be let out; but the husband firm and kept the door closed until she was reduced to ashes. The fakir then opened the oven, took out her ashes, and by their aid succeeded in transmuting base metals into gold. As for the husband, he was so overwhelmed with grief at the loss of his wife, whom he had dearly loved, that he went away and was never heard of again.

Mount Ararat As Seen From Etchmiadzin.[69]

Then there was the Vampire Dakhanavar, who once lived in the mountains and would not allow anyone to enter his domain. Anyone who ventured among the hills was bled by the vampire, who sucked their blood from their feet until dead. But one day two young men resolved to outwit the vampire and journeyed through the hills all day. When night came, they laid down together, taking care feet of each were placed under the other’s head. Before they were asleep, the vampire came and began to feel for their feet. After feeling for some time, and finding a head at either end, the vampire cried: “Well, I have gone through the whole of these 366 valleys, and have sucked the blood without end, but never before did I find anyone with two heads, and no feet.” Saying this, he left the mountain, and thus was known that the number of the valleys was 366.

Etchmiadzin Cathedral.[70]

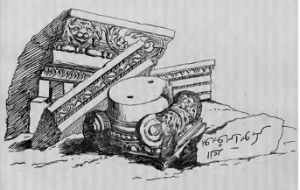

As for formal theological discourse, Lelya had many discussions with the monks in the nearby Monastery of the Etchmiadzin Cathedral. It was the See (dwelling-place) of the Armenian Apostolic Church, where their Patriarch, Nerses V, also lived.[71] Tradition stated that the original church was built in the early fourth century by Gregory the Illuminator when King Tiridates III adopted Christianity as the state religion. It was built over a pagan temple, to symbolize the triumph of the Christian conversion. Lelya consulted the monks once regarding an enormous column in the garden of the estate where she lived with Nikifor. It was a ruin from the palace of Tiridates and covered with inscriptions which she had reasons to believe were of Indian origin.[72]

Ruins Of Tridates.[73]

Some say it was three weeks, others say it was two months, but soon after their wedding, Lelya broke a chandelier over Nikifor’s head.[74] “The only reason I chose you over the other suitors,” Lelya bluntly told him, “is because I mind less making you miserable than anyone else.”[75] The reason she left him was this—she had no reason at all. Being very young, and finding that she could not possibly continue a relationship with a man she found revolting, she left. “He hated me because I did not love him,” she would say, “I hated him because he did love me. The attachment was a disgusting one.” She left Nikifor, but for reasons only known to herself, she decided to keep the name. Lelya, from that point forward, was Blavatsky. To add insult to injury, the Grand Duke ordered poor Nikifor to give Blavatsky three-thousand rubles a year.[76]

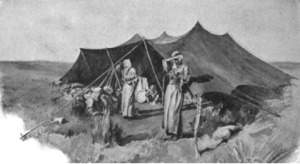

Kurdish Encampment.[77]

Leaving Erivan, Blavatsky found a guide to escort her to the Caspian Sea. She soon found herself traveling with a tribe of Kurds.[78] Naturally, she took the opportunity to study their fire-worshipping predilections. At sunrise and sunset, the horsemen lit a fire, and turned towards the sun, muttering prayers. They had a tent set apart made of a thick, black, woolen fabric. It was decorated with strange signs, worked in bright red and yellow. Inside the tent, in the center, there was placed a kind of altar, encircled by three brass bands, to which numerous rings were suspended by ropes of camel’s hair. At every new moon, they performed mysterious rites throughout the whole night, and the worshippers held these rings with their right hand during the ceremony. On the altar burned a curious relic, an oblong silver lamp with a handle and three wicks. Every Kurdish tribe had at least one greatly honored old man, regarded as “holy beings,” known as koodians (sorcerers) who knew the past and could divulge the secrets of the future. They were often resorted to for information in cases of theft, murders, or danger. Blavatsky witnessed this firsthand.

One day a very expensive saddle, a carpet, and two Circassian daggers, richly mounted and chiseled in gold, were stolen from a tent. The Kurds, with their chief at the head, took Allah as their witness that the culprit could not have belonged to their tribe. A Georgian belonging to their caravan suggested they resort to the light of the koodian. This was arranged in great secrecy and solemnity, and the interview took place at midnight, in the black tent when the moon was full. Radiant moonbeams poured in vertically through a large aperture in the arched-roof of the tent, mingling with the vacillating triple flame of the little lamp. The koodian, an old man of tremendous stature, with a pyramidal turban that scraped the roof of the tent, was directing incantations to the moon. After several minutes the conjurer produced a round looking-glass known as a “Persian mirror,” and unscrewed its cover. He then breathed on it for nearly ten minutes, wiping off the moisture from its surface with a satchel of herbs, while muttering more incantations. The glass became more brilliant after every polishing until its crystal seemed to radiate phosphoric rays in all directions.

“Look, Hanoum,” whispered the motionless koodian, the mirror still in his hand, “look steadily.”