While still in America (receiving money at intervals from her father) Blavatsky tried her hand at gold prospecting in California, near Sacramento.[1] Then she went to Peru, traveling with an Englishman whom she had met in Germany, and a Hindu “Chela,” whom she came across at the Mayan ruins at Copán, Honduras.[2] Questions were being asked about the “first peopling of America.” Some claimed that the Native Americans were a separate race, “not descended from the same common father with the rest of mankind.” Others ascribed their origin to “some remnant of the antediluvian inhabitants of the earth who survived the deluge which swept away the greatest part of the human species in the days of Noah.” In 1807 Alexander Von Humboldt published his theory that South America and Africa were once connected.[3] Having accepted that the two continents had been “rent asunder by the shock of earthquake,” the fabled island of Atlantis had been “lifted out of the ocean,” and into the popular imagination.[4] In his 1841 book, Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan, John L. Stephens told the story of a mysterious city, as recounted to him by a Spanish Padre, who swore to him that he had seen it with his own two eyes:

He had heard of it many years before at the village of Chajul and was told by the villagers that from the topmost ridge of the Sierra, this city was distinctly visible. He was then young, and with much labor climbed to the naked summit of the Sierra, from which at a height of ten or twelve thousand feet, he looked over an immense plain extending to Yucatan and the Gulf of Mexico, and saw at a great distance a large city spread over a great space, and with turrets white and glittering in the sun. The traditionary account of the Indians of Chajul is, that no white man has ever reached this city; that the inhabitants speak the Maya language, are aware that a race of strangers has conquered the whole country around and murder any white man who attempts to enter their territory. They have no coin or other circulating medium; no horses, cattle, mules, or other domestic animals except fowls, and the cocks they keep underground to prevent their crowing being heard.[5]

For Blavatsky, the similarities of the rites, ceremonies, traditions, and even the names of the gods, between the ancient peoples of Central and South America, and the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians, was sufficient proof that the “New World” was peopled by a colony which somehow found its way across the Atlantic. “When?” thought Blavatsky, “at what period?” History was silent on that point. Nevertheless, there was “no tradition, sanctified by ages,” she thought, “without a certain sediment of truth at the bottom of it.”[6]

The ruins that covered both Americas (and found on many West Indian islands,) were popularly attributed to the submerged Atlanteans. During her travels, she had learned of legends concerning the magicians of the now submerged country, and how they traveled between the old world and the new with a “network of subterranean passages running in all directions,” which, in the days of Atlantis, “was almost connected with the new one by land.” This theory was all but confirmed by her Peruvian guide, as they penetrated further into the interior of South America.

Ruins In The Jungle.[7]

“Since the well-known and miserable murder of the Inca by Pizarro,” he said, “the secret has been known to all the Indians, except the Mestizos who cannot be trusted.” The story, as it was told to her, was this. When the Inca leader, King Atahualpa, was imprisoned, his wife, Doña Angelina Yupanqui, offered Pizarro, in exchange for his freedom, a room full of gold “from the floor up to the ceiling, as high up as his conqueror could reach” before the sun would set on the third day. She kept her promise. Pizarro did not. “Marveling at the exhibition of such treasures, the conqueror declared that he would not release the prisoner, but would murder him unless the queen revealed the place whence the treasure came.” Pizarro had learned that the Incas knew the location of “an inexhaustible mine,” a subterranean tunnel that ran for many miles underground. It was here where they kept the accumulated riches of their country. The Inca queen begged for delay and went to consult the oracles. During the sacrificial rites, the chief-priest revealed to her in his consecrated black mirror, “the unavoidable murder of her husband, whether she delivered the treasures of the crown to Pizarro or not.” The queen then ordered the entrance of the mine (which was a door cut in the rocky-wall of a chasm) to be sealed shut. Under the direction of the chief priest, “the chasm was accordingly filled to the top with huge masses of rock, and the surface covered over so as to conceal the work.” King Atahualpa was murdered by the Spaniards as predicted, and his unhappy queen took her own life. “Spanish greed overreached itself, and the secret of the buried treasures was locked in the breasts of a few faithful Peruvians.” Their informant added that in consequence of certain indiscretions at various times, men had been sent by different governments to search for said treasure under the pretext of “scientific exploration.” They rummaged the country through, but without ever achieving their goal.[8]

Blavatsky returned to Europe; arriving in Paris, she made the acquaintance of Jules Janin (who secured her a writing job for the Parisian Press.) The Spiritualist movement, which emerged in Rochester, New York, in 1848, had, by now, firmly established itself in England and France. (There was something of a prequel to this new dispensation in France in 1846, however, with the “Electric Girl” of La Perrière.)[9] For European Spiritualists, speculating on the metaphysical significance of dialogue with the deceased developed into something of a semi-reputable scientific pursuit.[10] It was in this atmosphere that Church-sanctioned apparitions rapidly developed. In nineteenth-century, the Church and State in France were locked in a prolonged battle for the hearts and minds of the people, exemplified in the semiotics of “Marianne” (State,) and the Virgin Mary (Church.)[11] The more secular the nation became the greater the spiritual pushback. This manifested in some peculiar ways. There was also an unprecedented number of supernatural religious manifestations which occurred primarily in the religious manifestations of the Virgin Mary. There were so many heavenly visions that this period was referred to as an “epidemic of apparitions.” The dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary took on a crucial role during this period; a long-held Catholic belief, it became official doctrine in 1854.[12]

As for matters closer to her heart, the Crimean War, which began in 1853, was reaching the apex of violence.[13] The conflict, nominally fought over the Christian Holy Places in Jerusalem, was, in some respects, the last of the Crusades.[14] The demands of Russia stipulated that 1. All the Orthodox subjects of the Ottoman Empire would be under Russian protection. 2. That the patriarchate would be lifelong, and that no patriarchs would be dismissed. 3. A new Russian church and hospital would be built in Jerusalem, and put under the protection of the Russian consulate, and 4. A new firman would clearly point out all the rights of the Orthodox in the holy places in Palestine.[15] Throughout the nineteenth century, policy-makers in Britain maintained that the preservation of the Ottoman Empire was necessary to the balance of European power and was a sine qua non for British interests in India. The image of Turkey as the brave ally of Britain against Russia in Crimea was actively cultivated. The successive British governments (Whig, Tory, and Liberal,) however, impressed upon the sultans a need for reforming the entire structure of the Ottoman government. One primary concern was the treatment of the Balkan Christians in their empire.[16] Needless to say, the British, fearing the encroachment of Russia into India, were less than hospitable to the subjects of the Tsar. Blavatsky experienced this first-hand.

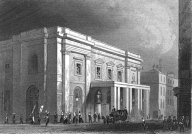

Drury Lane Theatre.[17]

She then went back to London where she turned heads with her musical talent as a member of a local philharmonic society. One evening, after a performance in the Drury Lane Theatre, a conversation was held in the lobby. The talk turned to Russian affairs, and Russians in general, in a tone that was unbearable to any true Russian. One fat lord began shouting and swearing—actually swearing—about the evils of Russia. It went without saying that the candied gentleman had never smelled the gunpowder in Sevastopol, and experienced butcheries only after it was on his plate.

“I am a Russian,” Blavatsky declared as she stood up, “and in the name of my nationality, I ask you to stop shouting.”

“I am an Englishman,” the lord replied impudently, “and we are in England!”

Blavatsky turned to the visitors who were sitting near her and appealed to them to stand up for her rights since she was a Russian woman, and a guest visiting England. Some people supported her, but the vocal majority raised their voices against her. Bolstered by the encouraging hostility directed at Blavatsky, the lord began speaking again, this time louder and with added vitriol.

“Your actions are mean, for you are insulting enemies who are far away, whom you do not know, and whose courage and merits you cannot judge,” said Blavatsky, pale with indignation. “If somebody does not make him stop shouting, I will stand for my nation. I will not permit him to continue calumniating Russians.”

“How, pray tell, will you accomplish that?” the Englishman said, mockingly. “Are your arguments really stronger than all the hundreds of thousands of your Russian armed forces? That would be interesting to see.”

“I would not recommend, for your own sake, that you get to see it. I don’t know now how I will do it, but I repeat—stop shouting or I will make you do so!”

“In such a case,” said the fat lord, roaring with laughter, “I certify that Russian women are more courageous than Russian soldiers who without hesitation flee the field, leaving it to our—”

Before he could even finish his sentence, a heavy candelabrum, filled with candles, whistled through the air and struck him in the face. He fell quickly, lingering on the ground in shock, transfixed by the growing puddle of his blood. He was taken away in a dead faint.

Legal proceedings were instituted against Blavatsky. To the credit of the English people, the judges sincerely considered all circumstances of the case and took the side of Blavatsky. However, Blavatsky was sentenced to pay the wealthy lord five pounds for exposing him to public ridicule. Standing straight in the courtroom, Blavatsky cheerfully offered ten pounds. “Advance payment,” she explained, “for possible future meetings with him.” The room burst into sincere laughter.[18]

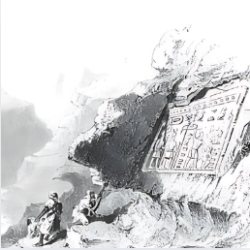

Blavatsky left the barbarity of London for a more civilized environment, returning to the jungles of Peru with a small band of adventurers. Traveling southward from Lima by water, they reached a point near Arica at sunset. She was immediately struck by the appearance of an enormous rock (apart from the range of the Andes,) nearly perpendicular, that stood in mournful solitude on the shore. It was the tomb of the Incas. The last rays of the setting sun struck the face of the rock, and using her ordinary opera-glasses, she could make out some curious hieroglyphics inscribed on the volcanic surface. Their mysterious Peruvian guide explained the history of the place which was substantially this:

When Cusco was the capital of Peru, it contained a temple of the sun, famed far and near for its magnificence. It was roofed with thick plates of gold, and the walls were covered with the same precious metal; the cave-troughs were also of solid gold. In the west wall the architects had contrived an aperture in such a way that when the sunbeams reached it, it focused them inside the building. Stretching like a golden chain from one sparkling point to another, they encircled the walls, illuminating the grim idols, and disclosing certain mystic signs at other times invisible.

It was only when one understood these hieroglyphics that one could learn the secret of the tunnel and its approaches. There was one hidden entrance near Cuzco that led to an immense tunnel stretching to Lima and southward to Bolivia. At a certain point, it was intersected by a royal tomb. Inside this sepulchral chamber were two cunningly arranged doors—or, rather, two enormous slabs that turned upon pivots and closed so tightly as to only be distinguishable from the other portions of the sculptured walls by the secret signs (whose key was in the possession of the faithful custodians.) One of these turning slabs covered the southern mouth of the Liman tunnel—the other, the northern one, of the Bolivian corridor. The latter ran southward, passing through Tarapacá and Cobija, for Arica was not far away from the little river called Payaquina.

Overgrown Ruins.[19]

Not far from that spot, there stood three separate peaks that formed a curious triangle that was included in the chain of the Andes. According to tradition the only practicable entrance to the corridor leading northward was in one of those peaks— “but without the secret of its landmarks, a regiment of Titans might rend the rocks in vain in the attempt to find it.” Even if someone were to gain an entrance and find their way as far as the turning slab in the wall of the sepulcher, and attempt to blast it out, the superincumbent rocks were so disposed as to bury the tomb, its treasures, and, as the mysterious Peruvian expressed it “a thousand warriors” in one common ruin. There was no other access to the Arica chamber but through the door in the mountain near Payaquina. Along the entire length of the corridor, from Bolivia to Lima and Cuzco, there were smaller hiding places filled with treasures of gold and precious stones, “the accumulations of many generations of Incas,” the aggregate value of which was incalculable. The mysterious Peruvian guide gave Blavatsky a cartographic gift that included an accurate plan of the tunnel, the sepulcher, and the doors. If she had ever thought of profiting from the secret, however, it would require the cooperation of the Peruvian and Bolivian governments on an extensive scale. To say nothing of physical obstacles, no one individual or small party could undertake such an exploration “without encountering the army of smugglers and brigands with which the coast is infested.” Then there was the mere task of purifying the mephitic air of the tunnel (which had not been entered for centuries.) The treasure remained safe, for as tradition states “it will lie till the last vestige of Spanish rule disappears from the whole of North and South America.”[20]

SOURCES:

[1] “A Heroine.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Brooklyn, New York) October 12, 1874; Rawson, A. L. “Mme. Blavatsky: A Theosophical Occult Apology.” Frank Leslie’s American Magazine. Vol. XXXIII (January-June 1892): 199-208.

[2] H. S. O. “Traces Of H. P. B.” The Theosophist. Vol. XIV, No. 7 (April 1893): 429-431.

[3] Harvey, Eleanor Jones. Alexander Von Humboldt And The United States: Art, Nature, And Culture. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2020): 27.

[4] Stephens, John L. Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan: Vol. I. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1841): 96.

[5] Stephens, John L. Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan: Vol. II. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1841): 195-1996.

[6] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. I. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 556.

[7] Stephens, John L. Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan: Vol. I. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1841): 157.

[8] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. I. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 547-548, 595-598.

[9] Owen, Robert Dale. “The Electric Girl of La Perrière.” The Atlantic. Vol. XIV, No. 83 (September 1864): 284-292.

[10] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. I” Rebus. No. 43–48 (October 28, 1884–December 2, 1884); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. II.” Rebus. No. 4–7 (January 27, 1885–February 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. III.” Rebus. No. 9–11 (March 3, 1885–March 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. IV.” Rebus. No. 13–14 (April 7, 1885–April 14, 1885.) [Preparation of the text and comments by A.D. Tyurikov. Bakhmut Roerich Society.]

[11] Ziolkowski, Jan M. The Juggler of Notre Dame And The Medievalizing Of Modernity: Volume II: Medieval Meets Medievalism. Open Book Publishers. Cambridge, England. (2018): 51-95.

[12] Garrigou-Kempton, Emilie. “Hysteria In Lourdes And Miracles At The Salpêtrière: Making Sense Of The Inexplicable In Charcot’s La Foi Qui Guérit And In Zola’s Lourdes.” In Quand La Folie Parle: The Dialectic Effect of Madness in French Literature Since the Nineteenth Century. (eds.) Gillian Ni Cheallaigh, Laura Jackson, Siobhan McIlvanney. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, England. (2014): 53-73; Stępień, Maciej B. “A Lifetime In Error: Helena P. Blavatsky And The Immaculate Conception.” Roczniki Kulturosznane. Vol. XII, No. 2 (June 2021): 31-52.

[13] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. I” Rebus. No. 43–48 (October 28, 1884–December 2, 1884); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. II.” Rebus. No. 4–7 (January 27, 1885–February 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. III.” Rebus. No. 9–11 (March 3, 1885–March 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. IV.” Rebus. No. 13–14 (April 7, 1885–April 14, 1885.) [Preparation of the text and comments by A.D. Tyurikov. Bakhmut Roerich Society.]

[14] Mandel, Neville J. “Ottoman Policy and Restrictions on Jewish Settlement in Palestine: 1881-1908: Part I.” Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. X, No. 3 (October 1974): 312-332.

[15] Badem, Candan. The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856.) Brill. Leiden, Netherlands. (2010): 76.

[16] Çịçek, Nazan. The Turkish Response to Bulgarian Horrors: A Study in English Turcophobia. Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. XLII, No. 1 (January 2006): 87-102.

[17] Gaspey, William. Tallis’s Illustrated London: Vol. II. John Tallis. London, England. (1851): 218.

[18] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna; (ed.) Deveney, John Patrick. “The Truth About H.P. Blavatsky.” The Newsletter Of The Friends Of The Theosophical Archives. Special Edition. (Summer 2015): 1-100.

[19] Stephens, John L. Incidents Of Travel In Central America, Chiapas, And Yucatan: Vol. II. Harper & Brothers. New York, New York. (1841): 339.

[20] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. I. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 547-548, 595-598.