In 1819, Andrew Jackson, and a company of his soldiers, made their way from Nashville to Robertson County, near Red River and Elk Fork Creek. Their destination, the Bell House, was only forty miles away from Jackson’s estate, “The Hermitage.” The wagon was loaded with a tent, provisions, etc. They were bent on a good time investigating the witch named “Kate.”[1] The men rode on horseback, following along in the rear of the wagon, discussing all the while how they were going to “do up the witch, if it made an exhibition of such pranks as they had heard of.”

There was a story of the Shakers who paid a visit to the Bell House. (This was a time when religious fervor had flared up in the wilderness of Tennessee and Kentucky; John Wesley’s Methodists had re-kindled the flame of Christian Perfectionism and inspired a Great Revival and the first Camp-Meetings.)[2] The Shaker missionaries were among the cast of characters in this drama on the spiritual amphitheater.[3] At the time they kept their trading men continually on the road, traveling through the country, dealing with the people on the frontier. They went in pairs (generally on horseback) and were easily distinguished from other people (at any distance) owing to their broad-brim hats and peculiarity in dress. The pair who traveled through this section always made it convenient to call on John Bell at his house for dinner or a night’s lodging. It was about the regular time for the Shakers to come around, and as the dinner hour approached, one of the Bell servants came to announce that the two gentlemen were coming down the lane. This was a notice to increase the contents of the dinner pot. “Kate” immediately spoke up. “Them damn Shakers shan’t stop this time!” John Bell was troubled a good deal by breachy stock on the outside pushing the fences down, and generally sent their servant, Harry, around every day to drive away stock and see that the fences were up. There were three large dogs on the premises that Harry always carried along, and he had them well-trained and always eager for a chase at his call. Harry was nowhere around, as he was out on the farm with the other hands. “Kate,” speaking in Harry’s voice, called the dogs. “Here Cesar! Here Tiger! Here Bulger! sic, sic!” Not a soul but the Shakers coming down the lane could be seen. The dogs, however, responded with savage, furious, yelping, following the phantom voice that led the way. Just as the Shakers were nearing the turning-in gate, the dogs jumped the fence at their horses’ heels. Harry’s “voice” was there too, hollering, “Sic, sic, take ‘em.” The Shakers put whip to their horses and the dogs chased after them. It was a lively chase, and the Shakers never came around again. “Kate” enjoyed the sport tremendously, laughing and repeating the affair to visitors, “injecting many funny expressions in describing the chase,” and how “the Shakers held on to their big hats.”[4]

Chasing The Shakers. [5]

“I’ll unravel the mystery within three days,” boasted the professional “witch hunter” who Jackson’s men brought along specifically to capture “Kate.” He was a brawny man with long hair, high cheekbones, a hawk-billed nose, and fiery eyes. The “witch-hunter” bragged much of his power over evil spirits, exhibiting the tip of a black cat’s tail, about two inches. “I shot the cat with a silver bullet while sitting on a bewitched woman’s coffin,” he said. By stroking that cat’s tail on his nose it would flash a light on a witch, even on the “darkest night that ever come.” The light, however, “was not visible to anyone but a magician” he explained. Once the whole invisible world was plain to his eye, “then the silver bullet would do the rest.”

Jackson was already weary of the braggart when the party came to a halt a short distance from the Bell House. The road was dry and firm, and the team was not over-driven. The driver snapped his whip, cursed, and shouted for the team to move. The horses pulled with all of their might, yet they could not move the wagon an inch. It was stuck as if welded to the earth. Jackson commanded all the men to dismount. He then told them to put their shoulders to the wheels and give the wagon a push. The order was promptly obeyed. The driver laid on the lash; the men and horses, likewise, did their best. It was all in vain. The wheels were removed, one at a time, and thoroughly examined. Everything seemed to be alright, revolving easily on the axles, etc. Another attempt was made to get away. The driver whipped up the team while the men pushed at the wheels. It was no use. Everyone stood off looking at the wagon in serious meditation.

After a few moments of thought (and realizing that they “were in a fix,”) Jackson threw up his hands. “By the Eternal, boys, it is the witch!”

“Yes, General, it is the witch,” a metallic voice called out. “You may go on now. I will see you again tonight.”

The men, in bewildered astonishment, scanned the area in every direction to find the source of the strange voice. They found no explanation for the mystery.

“By the eternal, boys,” Jackson exclaimed again, “this is worse than fighting the British!”

The horses then started unexpectedly of their own accord. The wagon rolled along as smoothly as ever.” [6]

~

Jackson’s parents, Andrew Jackson, Sr. and Elizabeth (neé Hutchinson) were Presbyterian Ulster-Scots settlers. The family’s hatred for the British began on the family farm in Northern Ireland. After the birth of two boys, Hugh and Robert, the Jacksons immigrated to America. They reached Charleston, South Carolina, after a long sea voyage in the early part of 1765. They soon settled at Waxhaw, a village in the frontier of Southern North Carolina. It was here that Andrew Jackson the younger was born. A “half-orphan” they say, for his father died a few weeks before his birth. A (very small) patrimony was left, but it was sufficient for a simple education. The pending contest for liberty was ever in the widowed mother’s thoughts, and all of her daily home education of the boys consisted of teaching them to despise the English. When Jackson was ten years old, he and his older brother Robert joined the Carolina Volunteers, who were then skirmishing with Redcoats that invaded their village. From his youngest days, Jackson became an expert with the shotgun, for in those days the free sons of Ireland, prevented at home from owning a firearm, fancied such use in another country. During one of the skirmishes Jackson, Robert, and some older comrades, were taken prisoner. They were treated harshly by their Tory jailer; as history teaches, the native Tories of the Colonial period were more overbearing and cruel toward their fellow colonists than were the foreign Brits. Jackson’s characteristic personal pride (which distinguished him throughout his career) was well illustrated while imprisoned. A Brit officer ordered him to kneel and brush the mud from his Hessian boots. When Jackson indignantly refused, the gallant, gold-laced captain, sliced the youth across the shoulder and ordered him into close confinement. Elizabeth was also in the Colonial Service in Charleston as a camp hospital nurse for wounded Continentals. The location enabled Elizabeth to include her sons on the list when an exchange of prisoners was made. Jackson returned to his uncle’s house, where he was rejoined by his mother. She was mourning the death of Hugh, who was killed during the Battle of Stono Ferry. Robert died a short time later, having contracted disease from exposure while imprisoned. Elizabeth soon followed her two oldest boys into immortality.

By the end of the war, Jackson was alone in the world. There was, however, no situation in life better calculated to teach self-reliance. Jackson apprenticed himself to a saddler, who drove a thriving trade, for in those days every man and woman rode a horse. In time, a local lawyer of Scotch-Irish descent, John McNairy, took Jackson under his wing and advised him to study law. Jackson accordingly began to read the recently published Commentaries of Blackstone and acquire knowledge of traditions and customs regarding the rights of personal property. His official term of study was at Salisbury, North Carolina, where his preceptor was an attorney of Irish descent named Spruce McCay.

What is now called Tennessee was, in 1788, known as the Western District of North Carolina. Jackson’s patron, McNairy, was appointed judge of the newly established court of the Confederated government. McNairy secured the appointment of Jackson as a public prosecutor to accompany him. Together, on horseback, they journeyed westward, over wild frontier country, to their new home in the Nashville Settlement. At the close of the eighteenth century, “the Star of Empire took its course westward,” following the trail of blood left by the advance guard who drove the Natives from their great country. (Already by 1790 there was a marked distinction between the North and South, between New England and the Middle States; between the Border and the Southern Slave States.)[7] Couriers carried back to the East glad tidings of peace and safety, and a glowing account of a wilderness teeming with possibilities. The land was rich, they said, the forests were bountiful, and the water was clean and plentiful. The land where Nashville was located was regarded as a “land of milk and honey.” The flow of immigration from North Carolina, Virginia, and other old States, soon became steady and constant, and the settlements rapidly appeared up the country. These settlers were “men of brawn and brain,” the “best blood of the land.” Along with the axe, plow, and sickle, they brought with them their customs, their notions of civilization, and their Christian religion. The Bible and the American Constitution were their guide.[8] In “a region given over to idleness, drink, debt, gambling, and quarrels,” Jackson was responsible for the care for law and order. The appearance of law and order at least. He acquired the confidence of William Blount, Governor of the Southwest Territory, who recognized his natural aptitude for public life.

In Nashville, Jackson lodged and boarded with the widow Donelson, whose beautiful daughter, Rachel, was the wife of a settler of French extraction named Louis Robard. He was often away from Nashville, and Jackson, a “fine-appearing, magnetic and insinuating man of twenty-two years” had his charms. Jackson and Rachel developed a platonic friendship, but Robard saw fit to accuse his wife of infidelity. Without either Jackson’s or Rachel’s knowledge, Robard went to Virginia (the place where he took his marital vows) to obtain a divorce. As soon as Jackson and Rachel heard that the Virginia Legislature had passed the divorce statute, “they at once went through the ceremony of wedlock.” A misunderstanding regarding the legal status of the divorce, however, caused no small amount of trouble for the newlyweds; and Jackson’s opponents took every opportunity to declare that Rachel committed bigamy. Apparently, during the process of divorce, Kentucky became a State (instead of a Territory of Virginia) and North Carolina turned over management of the Territory to the Federal government. Once the misunderstanding was remedied, Jackson and Rachel had a second wedding ceremony. It was said that “an imputation upon her, or a reflection upon the regularity of his marriage, always incensed him more than any other personal attack.”

Jackson briefly served in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, representing Tennessee. (After resigning, he served as a justice on the Tennessee Superior Court until 1804.) In 1801, Jackson was appointed Colonel of the Tennessee Militia. There was a story of how Jackson, an applicant for the Major Generalship of the Militia in 1803, met John Sevier, the Governor of Tennessee. Jackson happened to mention his services to the State and the Governor replied sarcastically.

“Do you refer to your service in leaving our State to go to another one and marry another man’s wife?”

“By the Eternal! (An expletive Jackson used throughout his life as a substitute for the French “Mon Dieu!”) You shall not mention her sacred name!”

Jackson drew a pistol.

Sevier followed his example.

Shots were immediately interchanged. No one died. It only served to frighten a group of bystanders.[9]

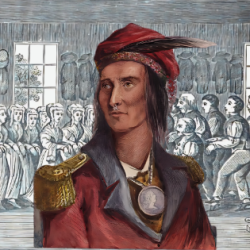

It was around this time when he purchased “The Hermitage” plantation. The crops, cultivated by enslaved men and women, made Jackson a wealthy man. Then the Napoleonic Wars shook Europe to the core, changing up the old order of things. There were more than a few who believed that Napoleon himself was the Anti-Christ and that Christ’s Second Coming was near at hand.[10] The same Great Comet of 1811 that guided Napoleon in Europe also inspired the dealings in America. The Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and his brother, “The Prophet,” had made progress in their efforts at creating an independent and segregated nation for the Native Americans.[11] When the Great Comet appeared he abandoned this plan. It was said that the Shawnee had wavered in their resolve. Since Tecumseh meant “Comet,” they had taken it as a bad omen. At that same time, on June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Britain.[12] During the concurrent war Creek War (1813–1814,) Jackson was victorious at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. He subsequently negotiated the Treaty of Fort Jackson whereby the indigenous Creek Nation was forced to surrender vast tracts of land (in what is now Alabama and Georgia.) The forty-seven-year-old General Jackson continued his success with his glorious victory over the British at New Orleans.[13] This made him a national hero. His men called him “Old Hickory” because of his willingness to share in the hardships of the common soldier. Jackson then commanded the U.S. army in the First Seminole War (which resulted in the annexation of Florida from Spain.)

~

Jackson’s party was not in a good frame of mind for camping out that night after the incident with their wagon. The whole party went to the Bell House for quarters and comfort. The owner of the property, John Bell, recognizing the distinguished leader of the party, was lavish in courtesies and entertainment. The men were expecting “Kate” to put in an appearance (according to promise,) and they chose to stay in a room by the light of a tallow candle. The “witch-hunter” held his big flint-lock horse pistol steady in his hand, loaded with a silver bullet as he kept a close lookout for “Kate.” He talked much, entertaining the company with details of his exploits and vain exhibitions of undaunted courage and success in defeating witches. The party flattered his vanity and encouraged his conceit, laughing at his stories and calling him such honorifics as “sage,” “Apollo,” “oracle,” “wiseacre,” etc. There was an expectancy in the minds of all; a residue from the wagon experience earlier that day which facilitated the “mage’s” stories, and everyone kept wide awake until a late hour when they eventually grew weary and drowsy. Jackson was the first one to let off tension, yawning and twisting in his chair.

“Sam,” said Jackson, in a disgusted aside to the man nearest him, “I wish the thing would make mince-meat of the braggart. I know he’s an errant coward. By the Eternal! I do wish the thing would come—I want to see him run.”

Jackson did not have to wait long.

A noise “like dainty footsteps” was heard prancing over the floor. This was quickly followed by the “metallic voice” coming from one of the corners of the room. “Alright, General, I am on hand ready for business.” The voice then addressed the “witch-layer,” saying: “Now, Mr. Smarty, here I am, shoot!”

The “mage” stroked his nose with the cat’s tail, leveled his pistol, and pulled the trigger. The gun failed to fire.

“Try again,” exclaimed the witch.

The “mage” did as “Kate” requested. Again, the gun failed to fire.

“Now it’s my turn! Look out, you old coward, hypocrite, fraud. I’ll teach you a lesson!”

A sound was then heard, like that of open-hand boxing. “Whack!” “Whack!” The “mage” tumbled over like he had been struck by lightning. Jumping quickly to his feet, he went “capering around the room like a frightened steer,” tumbling over everyone in his way, shouting, “Oh my nose, my nose, the devil has got me! Oh Lord, he’s got me by the nose!”

Suddenly, as if by its own accord, the door flung open and the “witch-hunter” dashed out, making a beeline at full speed for the lane and yelling at every jump. The men rushed out under the excitement, expecting the man to be killed. As far as they could hear up the lane, however, he was still running and yelling, “Oh Lord!” Jackson dropped down on the ground and rolled over with laughter. “By the Eternal, boys, I never saw so much fun in all my life! This beats fighting the British!”

“Kate,” who was on hand, joined in the laugh. “Lord Jesus,” she exclaimed, “How the old devil did run and beg—I’ll bet he won’t come here again with his old horse pistol to shoot me. I guess that’s fun enough for tonight, General. You can go to bed now. I will come tomorrow night and show you another rascal in this crowd.”

Jackson wanted to stay a week, but his men had enough of the “witch.” No one knew whose turn would come next, and no inducements could keep them. They spent the next night in Springfield and returned to Nashville the following day.[14]

~

Not long after, the United States experienced its first major financial depression during “The Panic of 1819.” Congress was forced to reduce the military’s size, and consequently abolish Jackson’s generalship. President James Monroe, in compensation, named Jackson the first Territorial Governor of Florida in 1821. Jackson only served in this capacity for two months, however, as ill health forced him to return to “The Hermitage.”

The Bell Witch. [15]

SOURCES:

[1] Ingram, M.V. An Authenticated History Of The Famous Bell Witch. Setliff & Co. Nashville, Tennessee. (1894): 15-17; Spraggett, Allen. “Andrew Jackson Heard Witch’s Voice.” The Robesonian. (Lumberton, North Carolina) October 17, 1973.

[2] Smith, Z. F. “The Great Revival Of 1800: The First Camp-Meeting.” Register Of Kentucky State Historical Society. Vol. VII, No. 20 (May 1909): 19, 21-35; Johnson, James E. “Charles G. Finney And Oberlin Perfectionism: Pt. I.” Journal Of Presbyterian History. Vol. XLVI, No. 1 (March 1968): 42-57.

[3] Winiarski Douglas L. “Seized By The Jerks: Shakers, Spirit Possession, And The Great Revival.” The William And Mary Quarterly. Vol. LXXVI, No. 1 (January 2019): 111-150.

[4] Ingram, M.V. An Authenticated History Of The Famous Bell Witch. Setliff & Co. Nashville, Tennessee. (1894): 152-153.

[5] Ingram, M.V. An Authenticated History Of The Famous Bell Witch. Setliff & Co. Nashville, Tennessee. (1894): 156.

[6] “Witchcraft Down South.” The Larned Eagle-Optic. (Larned, Kansas) August 3, 1894.

[7] “There was in 1790 a marked distinction between the North and South, between the New England and the Middle States between the Border and Southern Slave States “Mason and Dixon’s line,” as it was called from the surveyors to whom the demarcation of the artificial frontier between Maryland and Pennsylvania was entrusted, was the boundary of two essentially different and constantly diverging civilizations. No phrase is of more frequent occurrence in American history, politics, and satire. It is used seldom or never in its strict geographical sense, as marking the State line commencing with the Delaware and ending on the Upper Ohio, but as the border between North and South, between slavery and freedom. It acquired this use while as yet slavery existed, legally and practically, in many of the so-called Free States. In this sense it divided nations of common blood and language, but in character, thought, social institutions, economy, and industrial organizations, more unlike than France and Spain, Germany and Russia.” [Greg, Percy. History Of The United States From The Foundation Of Virginia To The Reconstruction Of The Union: Volume II. West, Johnston & Company. Richmond, Virginia. (1892): 134.]

[8] Ingram, M.V. An Authenticated History Of The Famous Bell Witch. Setliff & Co. Nashville, Tennessee. (1894): 15-17.

[9] Hall, A. Oakey. “Andrew Jackson. His Life, Times And Compatriots: First Paper—Andrew Jackson’s Private Life.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XLIV, No. 5 (November 1897): 487-497.

[10] In 1809, an anonymous pamphlet was published in New York titled, The Identity Of Napoleon And Antechrist, which connected passages from the Biblical Book Of Revelation and Book Of Daniel to the exploits of Napoleon. In 1811, the Reverend William C. Davis of South Carolina, published a sermon titled, The Millennium, Or Short Sketch On The Rise And Fall Of Antichrist, in which he contends that Napoleon is the titular villain. Similar themes were found in the sermons of the New England preachers Ethan Smith and Elijah Parish, both of which tied Napoleon’s sacking of Rome and imprisonment of the Pope as clear signs of the imminent eschaton. Then there was the Lutheran pietist clergyman, Johann Albrecht Bengel, who predicted that Jesus Christ would return in 1836 and begin His 1,000-year reign, known as the Millennium. [Pesenson, Michael A. “Napoleon Bonaparte And Apocalyptic Discourse In Early Nineteenth-Century Russia.” The Russian Review. Vol. LXV, No. 3 (July 2006): 373-392.]

[11] Smelser, Marshall. “Tecumseh, Harrison, And The War Of 1812.” Indiana Magazine Of History. Vol. LXV, No. 1 (March 1969): 25-44.

[12] “Fiery Sword In The Sky Draws All Eyes.” The World. (New York, New York) March 8, 1898; Koenig, Duane. “Comets, Superstitions, And History.” Quarterly Journal Of The Florida Academy Of Sciences. Vol. XXXI, No. 2 (June 1968): 81-92.

[13] Warshauer, Matthew. “The Battle Of New Orleans Reconsidered: Andrew Jackson And Martial Law.” Louisiana History: The Journal Of The Louisiana Historical Association. Vol. XXXIX, No. 3 (Summer 1998): 261-291.

[14] “Witchcraft Down South.” The Larned Eagle-Optic. (Larned, Kansas) August 3, 1894; Ingram, M.V. An Authenticated History Of The Famous Bell Witch. Setliff & Co. Nashville, Tennessee. (1894): 231-235.

[15] Ingram, M.V. An Authenticated History Of The Famous Bell Witch. Setliff & Co. Nashville, Tennessee. (1894): Frontispiece.