The mummy case in question in the catalogue of the British Museum was No. 22,542. The mummy that it originally covered, however, was never brought to England. This is what W. T. Stead told Frederick K. Seward at the ship’s saloon table. Though the immediate purpose of the veteran English journalist’s visit to America was to aid in the New York campaign of the Men and Religion Forward Movement, Stead talked much of Spiritualism, thought transference, and the occult.[1] Any person who wrote the story of the mummy case, Stead said, was punished with great calamities. He told of one person after another who “had come to grief after writing the story,” adding that, “although he knew it, he would never write it.” (He did not say whether such ill luck was attached to the mere telling of it.)[2] It was in 1909 when Stead heard the very startling report, which, however, he was not unprepared for. It was said that because of the number of “accidents” that had occurred to visitors of the Egyptian Room where the famous mummy case lid of the royal priestess, Amen Ra, was to be removed from the room where it has been exhibited for several years.

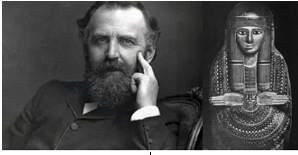

William T. Stead relating the story of Mummy.

“More than thirty years ago this case was brought from Egypt by a party of four young gentlemen who had been enjoying a holiday on the Nile,” said Stead. “One of these is a personal friend of my own. I have a letter from him—written with his left hand. For on him, the wrath of the offended priestess was the first to fall. Before he left Egypt his fowling piece exploded, shattering his right arm. He was about to enter the lifeguards, and the accident blighted his military career. That was more than thirty years ago.”

From that time onward an uninterrupted series of accidents and fatalities had been recorded by all who had offended the ireful shade of the princess priestess who left this earthly plane a thousand years before the Christian era. On the return journey, one of the members of the party was accidentally shot in the arm by his servant, through a gun that discharged without visible cause. The arm had to be amputated. Another died in poverty within a year. A third was shot. The owner of the mummy case found, on reaching Cairo, that he had lost a large part of his fortune and died soon after.

“Possession means disaster,” said Stead. “The case passed to the sister of one of the luckless quartet. From the time it entered her house misfortune after misfortune rained upon its occupants. She sent it to be photographed. When the negative was developed it was discovered that in place of the pictured features on the lid, the photograph showed the face of a living Egyptian woman of malevolent aspect. Within the year the photographer committed suicide.”

Stead & Amen Ra.

The priestess of Amen-Ra showed her displeasure convincingly. When the case arrived in England, it was given by its owner, Mr. W—, to a married sister living near London. One day the Theosophist, Madame Blavatsky, entered the room in which the case had been placed. She soon declared there was a “most malignant influence in the room.” On finding the cover, she begged her hostess to send it away, declaring it to be “a thing of the utmost danger.” The lady, however, laughed at this idea as a foolish superstition.”[3]

She sent the case to a popular photographer in Baker Street. Within a week he called upon her in great excitement, to say that while he had photographed the face with the greatest care and could guarantee that no one had touched either his negative or the photograph, the photograph showed the face of a living Egyptian woman staring straight before her with an expression of singular malevolence. The photographer died suddenly and mysteriously shortly after.

“Misfortune continuing, the lady decided to send the case to the British Museum,” said Stead. “The man who took it to the Museum died in a week, and the man who helped him to carry the case into the building met with a serious accident. From that day the haunted lid has been a source of innumerable accidents. When it was photographed in the museum, the photographer smashed his camera, cut open his face and one of his children had a narrow escape from drowning. An old acquaintance of mine, B. Fletcher Robinson, a man hale and hearty and in the prime of life, wrote the story of the priestess for The Daily Express, and within a few weeks, he died.[4] An American magazine commissioned a correspondent to write the story of the haunted lid. He died before he completed the copy. All this happened before 1905. Since then the fame of the lid has been well established; many persons avoided the Egyptian room in the Museum, or when they visited it gave No. 22,542 a wide berth. Others more daring mocked the lid, and in many cases suffered for their temerity.”[5]

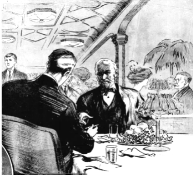

“Egyptian Antiquities In The British Museum.”[6]

Little did anyone know that their ship, the R.M.S. Titanic, was tearing through the April night to her doom. Contrary to the general expectation, there was no jarring impact when the vessel struck the iceberg.[7] Perhaps Stead thought about a piece he wrote for The Pall Mall Gazette nearly three decades earlier. “How The Mail Steamer Went Down,” was a fictional account that warned of the perils that would befall passengers should there be an insufficient number of lifeboats.[8] It was now a prophecy. “For it was in the whirling suction which followed the burial of the Titanic, in the rush and swirl and horror of fear dumbed death at sea that W.T. Stead went into that land from which in life he drew messages.”[9]

SOURCES:

[1] “Stead, Estelle W. My Father, Personal & Spiritual Reminiscences. George H. Doran Company. New York, New York. (1913): 374-378.

[2] “The Ghost Of The Titanic.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) May 5, 1912.

[3] St. Russell, G.. “The Mysterious Mummy.” Pearson’s Magazine. Vol. XXVII, No. 12 (August 1909): 163-172

[4] Robinson, B. Fletcher. “Priestess Of Death” The Daily Express. (London, England) June 3, 1904.

[5] Stead, William T. “Ghost Of Mummy Haunts The British Museum; Must Go Now.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) August 15, 1909.

[6] “Egyptian Antiquities In The British Museum.” Illustrated London News. (London, England) December 28, 1889.

[7] Mowbray, Jay Henry. Sinking Of The “Titanic.” National Publishing Company. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1912): 45, 49.

[8] Stead, W.T. “How The Mail Steamer Went Down In Mid Atlantic By A Survivor.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England.) March 22, 1886.

[9] Everett, Marshall. Wreck And Sinking Of The Titanic. L.H. Walter. Chicago, Illinois. (1912): 127-128.