Mabel Collins (1851-1927) was born Minna Mabel Collins in 1851 at St Peters Port, Guernsey, and though never formally educated, she proved a skilled writer since childhood. In 1871 Mabel married Keningale Robert Cook, a stockbroker, writer, and former editor of The Dublin University Magazine. Both Mabel and Keningale contributed numerous articles to magazines, mostly on topics concerning education, fashion, and women in the arts. (Mabel was a fashion columnist for Edmund Yates’ periodical, The World.) The couple lived for some time in a house in the Adelphi the looked upon the Thames. Mabel found married life tedious, and feared that “her brain was atrophying,” from boredom.

Cleopatra’s Needle.

In 1878 an obelisk brought from Egypt known as Cleopatra’s Needle was installed on the bank of the Thames just outside her window. From the very first moment she saw the Needle, she was “aware of a face in it,” that “was not visible to anyone else.” It was the face of an Egyptian, “full of power and will, and intensely alive.” The face was the same width as the Needle, which impressed upon her mind that it was an “imprisoned being” of some kind, that was “too large for the space in which it was confined.” Mabel soon noticed that “strange-looking men” began visiting the obelisk—men who were “dressed in a peculiar garb.” One day a group of such men, a procession of white-robed priests entered her house through the front door and walked up the stairs into her room and encircled her. This event would be repeated regularly, and each time they visited, Mabel would enter a trance state of psychography, or automatic-writing, whereby a different consciousness took control of her hands to produce “sheet after sheet” of composition that would later be published under the title The Idyll of the White Lotus. Blavatsky writes of this time:

I came to London, via Paris, about August 1884; went to Elberfeld, returning in October; and finally left for India on November 11th of the same year. It was only shortly before my departure that I met [Mabel Collins.] I saw her barely half a dozen times, and never alone […] When I met her, she had just completed the Idyll of the White Lotus, which, as she stated to Colonel Olcott, had been dictated to her by some “mysterious person.” Guided by her description, we both recognized an old friend of ours, a Greek, and no Mahatma, though an Adept; further developments proving we were right […] When I left for India in November 1884 [Light on the Path,] was not in existence.[1]

The work which brought her attention from the Theosophists was another psychographical production that would be called Light On The Path. While writing it, Mabel described being in a “wide-awake state,” and was transported to “some large library,” which she called the “Hall of Learning.” It was originally published in the New England Spiritualist journal, The Banner of Light. G.B. Finch, President of the London Lodge, re-published Light on the Path in 1885 as a brochure, and distributed it among the members, “to their great pleasure and satisfaction.” It was “used by faithful Theosophists much as orthodox sinners use their prayer-book.”[2] Mabel then became a “devoted disciple” of Blavatsky. It was Blavatsky who told Mabel that the author whom she “channeled” was none other than Hilarion, a Cyprian Adept who was affiliated with the White Lodge.[3] The work was volleyed back to America where it was also praised.

~

One American who felt a connection with Light on the Path was a stern, square-faced, woman with short black hair and piercing hazel eyes named Vittoria Cremers (1860-1837.)[4] Born Vittoria Cassini to a British nobleman and Italian mother in 1860, she immigrated to America in 1875. Settling in New York, she would eventually establish, and edit, the theatre magazine, The Stage Gazette.[5]

In 1886 Vittoria met Baron Louis Cremers at Felix’s boardinghouse.[6] Cremers was a young lieutenant from St. Petersburg, Russia, who served in that country’s aristocratic cavalry regiment, the 15th Hussars.[7] He was the son of a wealthy Russian banker with whom he shared his name, and nephew of Karl Von Struve, the Russian Minister to Washington, D.C. Cremers was fascinated by Vittoria and took pity on her “financial embarrassments.” Vittoria proposed marriage within a few weeks of meeting, and Cremers agreed. They were married in in New York in November 1886. Cremers says the officiant of the wedding was Pastor Goebel, so the wedding likely occurred at the Prospect Hill Reformed Church (Eighty-fifth Street between Second and Third Avenues) where Rev. G.A.T. Goebel was installed as Pastor in 1884.[8]

They were only a married a few weeks when Vittoria revealed to him that she “could not possibly love any man.” Baron Cremers “assured her that if she was a true and loyal wife,” he “would condone the past and trust [his] future in her hands.” He provided her a good income, and they lived for some time at The Belvidere and other costly hotels on 48th Street.[9]

Cremers very quickly became “exceedingly friendly” with James Jewell, and English immigrant in his mid-fifties who worked as a shoemaker at 21 East Fifteenth Street, Manhattan.[10] Jewell, “a Socialist, a Theosophist, and swelled up with all sorts of theories,” lived on South Fifth Avenue with his wife, Harriett, and their two daughter (a sixteen-year-old named Minnie, and a twelve-year named Elizabeth.)[11] Vittoria frequently called on Jewell and remained in his company for 7 hours a day on some days, as well as taking him to the theatres where they socialized with notable performers, like Sarah Bernhardt.

Jewell exercised a very potent, and “anything but beneficial influence on the conduct of [Vittoria,] to such an extent that she adopted in their entirety his fierce and bloodthirsty ‘Anarchistic’ and ‘Socialistic’ theories,” all of which were repugnant to Baron Cremers, and which he objected to with a good deal of emphasis. Vittoria disobeyed his wishes, “declaring that Jewell was a man who might well be taken for a model of humanity—in fact, her ideal of the modern civilized man.” Through her new exposure to Theosophy, Vittoria was introduced to Mabel’s Light on the Path, and was captivated by the book and the author.[12] It was at this time that Baron Cremers learned that prior to their marriage Vittoria “displayed extraordinary infatuation for actresses,” and “had the habit of going out in boy’s clothing to see the town.” Vittoria then disclosed other previously unknown biographical information. “She was a bastard,” and that “she had had many love affairs with women.” The only reason she married Baron Cremers, claimed Vittoria, was to win a bet regarding whether or not she could have sexual relations with a man.[13]

Finding it impossible to induce Vittoria to give up the acquaintance with Jewell and seeking to put an end to the source of never-ending irritation, Cremers consented to meet Jewell in December 1886 at the shop in which he and his family worked. Cremers found the shoemaker “malodorous individual,” in a state of abject poverty. Nevertheless, Cremers hoped to mitigate “an evil [he] could not wholly get rid of,” by cultivating Jewell’s acquaintance. He did this by giving him orders for shoes and recommending his service to his friends.

Jewell separated from his wife shortly after meeting Vittoria, and Harriett and their daughters moved to 141 East Thirteenth Street.[14] The marriage between Vittoria and Cremers would not survive the year.

~

In 1887 Blavatsky moved to London from Ostend, Belgium, with the assistance of Dr. Archibald “Arch” Keightley and his uncle (though junior in age) Bertram “Bert” Keightley.[15] For the first few months of her stay, Blavatsky lived with Mabel in her home in Upper Norwood in a small villa called Maycot. Keningdale Cook died in 1886, and left Mabel enough money to live comfortably for some time. In 1887 Mabel published Through the Gates of Gold and The Blossom and the Fruit. Once installed in London, Blavatsky tasked Mabel and the Keightleys with editing The Secret Doctrine.[16] The living arrangement was less than ideal. Alice Cleather, a member who joined the Society in 1885, gives us a glimpse into the living arrangement.[17] While en route to Maycot to pay a first visit to Blavatsky with Bert Keightley (whom Cleather met shortly after joining,) she was made aware of the volatile domicile:

I well remember [Bert] telling me on our way out to Norwood that, in their frequent “arguments,” [Mabel] and H. P. B. could be “heard halfway down the road”—when the windows were open! We walked from West Norwood station and, sure enough, when we got within about a hundred yards of Maycot, I heard loud and apparently angry voices floating—or rather ricocheting—towards us down the road. I was rather aghast, and [Bert’s] murmured remark that he was afraid “the old Lady” was in “one of her tempers.”[18]

By September 1887 newly living arrangements were made; Mabel moved to Clarendon Road, and Blavatsky, the Countess Wachtmeister, and coterie of Theosophists established themselves at 17 Lansdowne Road, sharing a space for some time with the Theosophist, Platon Drakoules.[19] Drakoules, who shared close ties with the Fabians, was the founder-editor Greece’s first Socialist magazine, Arden.[20] Perhaps he lent his assistance to Blavatsky who began her publication, Lucifer, in September 1887 with Mabel as co-editor.[21]

At this time an American Theosophist named Dr. Elliott Coues entered the picture. He joined the Society in 1884, and a few months later he was made President of the Board of Control for the American Section of the Theosophical Society.[22] He soon established the Gnostic Branch T.S. in his home city, Washington, D.C. (which was something of a rival to W.Q. Judge’s Aryan Branch in New York.)[23] In the summer of 1886 the American Board of Control was dissolved and replaced with the American Section of the Theosophical Society.[24] The administrative influence which Coues once possessed was now greatly reduced, which wounded his pride.[25] In September 1887, Blavatsky sent a letter to W.Q. Judge urging him to make peace with Coues for the sake of the Society:

[Coues] is vindictive because he is proud, & if you make of him an enemy now—you will have murdered theosophy in the U.S. with your own hands. Vindictive he is, lying & tricky no. You do not know him. He is a sensitive & a terrible one. He is more than a medium, for he deceives not only his “sitters” & public but himself—which other mediums do not. He is a self-hypnotic to the last degree. He is that so much so, that while some of his “tricks” are apparent to you, they are truth & fact for him. He is what Mahomet was, yet Mahomet founded a religion which with all its faults is a 1000 times better than any except Buddhism. What matters it to you his Karma if he obtains or creates good results for theosophy? Coues is our last trump-card. If you lose him, you & the Cause will have lost their battle. I tell you so. It is our Waterloo. Olcott is too weak though firm in appearance.[26]

Coues wrote a letter to Mabel at this time in which he praised her work and asked her “about its real source.”[27] Mabel quickly wrote back:

72 Clarendon Road,

Notting Hill, W., London.

The writer of The Gates of Gold is Mabel Collins, who had it as well as Light on the Path and the Idyll of the White Lotus dictated to her by one of the adepts of the group which through Madame Blavatsky first communicated with the Western world. The name of this inspirer cannot be given, as the personal names of the Masters have already been sufficiently desecrated.[28]

~

On December 2, 1887, James Jewell was arrested and taken before the Essex Market Court and held without bail. His youngest daughter, Elizabeth Jewell, was placed in Ward 30 at Bellevue Hospital the following morning. On the blotter at the hospital the diagnosis was given as “abortion.” She told the press that her own father had forced her “to submit to him.”[29] Jewell wrote a lengthy note to Vittoria from prison claiming that it was Baron Cremers who actually “betrayed his daughter.” Vittoria and Jewell, conspiring together, convinced Elizabeth to prefer charges against Baron Cremers over her father.[30] Elizabeth retracted her accusation against Cremers the following day and admitted to Eldridge Gerry’s Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, that her father was to blame.[31] The humiliation of such a dishonor was too much for Cremers to accept. On December 10, 1887, Cremers filed a libel suit against the papers which defamed him, and fully ventilated the story of his relationship with Vittoria.

In an effort to flee from spotlight, Vittoria joined the Theosophical Society on Christmas Eve, 1887, and fled to England in early 1888, where she lived 17 Lansdowne, and quietly worked on editing Lucifer.[32] The day after she joined (Christmas Day 1887,) The Sun (New York) published a three-column spread on the recently-published Hodgson SPR Report titled “Bogus Miracles Exposed.”[33] Vittoria quickly became a promising addition to the Lansdowne Road. When fellow Theosophists questioned her about her opinion of the Hodgson Report, Vittoria stated that she read it, and thought that it was a “well-written and interesting production.”[34] Cremers would withdraw his divorce suit against Vittoria by April 1888.[35]

APRIL 1888 CONVENTION

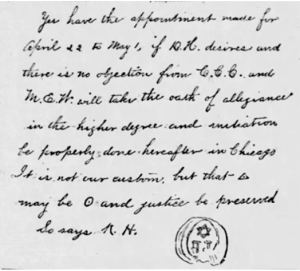

Facsimile of “Mahatma Letter” published in The Chicago Tribune.[36]

After the Convention The Chicago Tribune printed a facsimile of an alleged rare letter from Koot Hoomi in which he gives his approval for the Convention to be held at The Sherman House. The article stated:

The Tribune is sorry that is unable to reproduce the rice-paper envelope on which the letter came in. The paper on which the letter was written was also rice paper […] The above is really a genuine reproduction of Koot Hoomi’s letter, which did not come by mail, but suddenly materialized one day on the desk of the person to whom it was addressed. [37]

The letter aroused considerable curiosity in the general public, and a decided interest among American Theosophists. No public notice was taken of the matter by either Blavatsky of Judge, but the latter wrote privately to Coues. On May 21, 1888, Coues wrote to Judge:

I think that on reflection you will find yourself a little hasty in pitching into me about that Tribune matter […] Now I saw that letter of which you complain fall down from the air over a person’s head, precisely in the same manner as you have seen a like letter fall—one, of which we have since heard a good deal. The writing on one side was in that peculiar hand which I have learned to recognize in several expressions of the will of the Blessed Masters which you have been good enough to send me […] The writing on the other side must have been subsequently precipitated and the seal affixed […] If [Koot Hoomi] had not wished about 75,000 persons to be advised of the mode in which he brought about the Convention in Chicago he could easily have dematerialized the document […] It was clearly the will of the Brotherhood that the T.S. should be thus broadly advertised—and no doubt it would also be by the will of the same august personages, if the [Religo-Philosophical Journal] for example should contain some day a column or two explaining the delicate and mysterious manner in which rice-paper communications are “precipitated” out of the Akasa.[38]

This was a tacit admission by Coues that he had furnished the “message” to The Tribune, and that he “saw” it precipitated, and an insinuation that he had received from Judge similar messages. Judge wrote back that the Coues’s whole tale was a work of fiction originating in Coues’s own brain. Coues wrote to Judge on June 11, 1888:

But now comes another trouble. It appears, and not from “Coues’ brain,” but from a much more material and very likely much stupider source, that you have been opposing my long standing candidacy for the esoteric presidency, in order to keep the ostensible control of T.S. in your own hand and make yourself the real or actual head of the concern in America, leaving me only as a figure-head; and I am referred to all and any newspaper reports which emanate from the Aryans or yourself, as carefully suppressing or at least not putting forward my name, etc.[39]

It was well-known among members of the American T.S. that Coues had broadly hinted at his own Occult relations with the Mahatmas. Neither Blavatsky nor Judge confirmed his claims but were suspicious to his ulterior motive. It was Coues’s ambition to be the public head of the America T.S. and endeavored to gain the powerful support of Blavatsky. A part of his campaign to discredit Judge with his own pretended “messages.”[40]

THE PALL MALL GAZETTE

In December 1888 Vittoria entered a room at Lansdowne where she found Blavatsky seated at her card-table with a newspaper spread out before her. Arch and Bert hovered above her raining a torrent of inquiry.[41] The article in question was titled: “The Whitechapel Demon’s Nationality: And Why He Committed The Murders,” in the December 1, 1888, issue of The Pall Mall Gazette. The article, attributed only “To One Who Thinks He Knows,” stated:

Now, in one of the books by the great modern occultist who wrote under the nom de plume of “Eliphaz Levy,” “Le Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie,” we find the most elaborate directions for working magical spells of all kinds. The second volume has a chapter on Necromancy or black magic, which the author justly denounces as a profanation. Black magic employs the agencies of evil spirits and demons, instead of beneficent spirits directed by the adepts of la haute magie. At the same time he gives the clearest and fullest details of the necessary steps for evocation by this means, and it is in the list of substances prescribed as absolutely necessary to success that we find the link which joins modern French necromancy with the quest of the East-end murderer. These substances are in themselves horrible, and difficult to procure. They can only be obtained by means of the most appealing crimes, of which murder and mutilation of the dead are the least heinous. Among them are strips of the skin of a suicide, nails from a murderer’s gallows, candles made from human fat, the head of a black cat which has been fed forty days on human flesh, the horns of a goat which has been made the instrument of an infamous and capital crime, and a preparation made from a certain portion of the body of a harlot. This last point is insisted upon as essential; and it was this extraordinary fact that first drew my attention to the possible connection of the murderer with the black art.[42]

Two days later, W.T. Stead would write in The Pall Mall Gazette: “The contributor in question, is an occultist of some experience. When he was a lad of eighteen, he studied necromancy under the late Lord Lytton at Alexandria. It would be odd if the mystical lore of the author of ‘Zanoni’ were to help to unearth Jack the Ripper.”[43] Stead would later confess: “For more than a year I was under the impression that he was the veritable Jack the Ripper; an impression which I believe was shared by the police, who, at least once, had him under arrest.”[44]

“The Whitechapel Demon’s Nationality” was read before the members of the Blavatsky Lodge because of interest in the murders and the occult subject expressed in the article. The Indian Theosophist, Bhaskaranand Saraswati, who was studying in London at the time, states: “I noticed that the English women were afraid to walk abroad, and it made me think of the origin of the habit of our women of wearing veils and being secluded because of the Mohammedans, who, in their eyes, were so many friends like ‘Jack the Ripper.’”[45] The question of Black Magic appears have been on the mind of Mabel, as a conversation on the subject between her and Blavatsky appeared in the December 1888 issue of Lucifer:

No one should go into occultism or even touch it before he is perfectly acquainted with his own powers, and that he knows how to commensurate it with his actions. And this he can do only by deeply studying the philosophy of Occultism before entering upon the practical training. Otherwise, as sure as fate—he will fall into Black Magic.[46]

The article intrigued Mabel, so she wrote a letter to the mysterious author care of W.T. Stead. After some weeks she received a reply. Mabel states:

It was only a few lines saying that the writer was ill in hospital, but as soon as he was better, he would write and make an appointment. Again some weeks passed by before I heard anything and then a letter arrived from a Dr. Dr. D’Onston making an appointment—a marvelous man […] a great magician who had wonderful magical secrets.[47]

On January 3, 1889, another article appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette from the author of “The Whitechapel Demon,” called “The Real Origin of ‘She.’” The article stated:

The psychological and psychical portions of Rider Haggard’s She strike me as being not so much the creation of a vivid imagination as the simple recital—or, perhaps one should say, the skillful adaptation—of facts well-known to those who penetrated the recesses of the West Coast of Africa a generation ago. Astounding, terrifying, and incredible as the powers of Ayesha appear to the casual reader, yet to the men who laboriously threaded the jungles and swamps of the riverain portion of West Africa, long before Stanley was thought of, they only seem like a well-known and familiar tale. The awful mysteries of Obeeyah (vulgo Obi) and the powers possessed by the Obeeyah women of those days, were sufficiently known to all the slave-traders of the West Coast to make the wonders worked by “She” seem tame by comparison. And, always excepting the idea of the revivifying and rejuvenating flame in the bowels of the earth in which “She” bathed, there is nothing but what any Obeeyah woman was in the habit of doing every day.[48]

Evidently Mabel was not the only person who was interested in the article. In the February 15, 1889, issue of The Pall Mall Gazette another article by D’Onston appeared titled “What I Know Of Obeeyahism.” In it he writes:

The unexpected and extraordinary amount of interest excited by my article in The Pall Mall Gazette […] and the numberless letters of inquiry which I have received, have decided me to give a few particulars with regard to Obeeyahism which will, I think, give all the information my correspondents desire. First, then, the very root and essence of Obeeyahism is “devil worship”—i.e., the use of rites, ceremonies, adjurations, and hymns to some powerful and personal spirit of evil, whose favor is obtained by means of orgies which for horror, blasphemy, and obscenity cannot have been exceeded—if, indeed, they have ever been equaled—in the history of the world. These things are too utterly horrible even to be hinted at. It is the fashion at present to deny the existence of Satan, Shaitan, Ahrimanes (or whatever you please to call the incarnation of all evil.) But all occultists, of whatever school, know that everything in Nature has its counter. part, that you cannot have light without shadow, heat without cold, good without evil, nor yet a personal Deity without an equally personal evil principle.[49]

TANTRIC

In the winter of 1889, a rumor circulated that Vittoria was expelled from Lansdowne Road when Blavatsky learned that she found the Hodgson Report a “well-written and interesting production.” Blavatsky apparently sent word to Vittoria in “vigorous and mutilated English,” to depart the house, and Cremer, subsequently, went to Mabel and “as from a fortalice, shot criticisms and assertions and all kinds of harsh words.”[50] According to Vittoria, however, her departure from the house owed to entirely different circumstances.

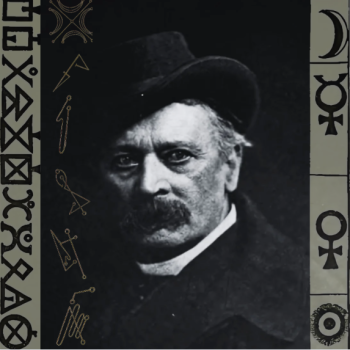

Mabel Collins.

Mabel pleaded with Blavatsky to accept her in the Esoteric Section, but Blavatsky was reluctant to do so. She was eventually placed on probation, but within four days, according to Blavatsky: “[Mabel] broke her vows, becoming guilty of the blackest treachery and disloyalty to her Higher Self.”[51] Vittoria states that Blavatsky learned that Mabel was at one time engaged to Arch Keightley, and that they had taken part in a Tantric ritual performing certain sexual Black Magic Rites. This in itself was quite scandalous, but it seems that Mabel performed said Tantric rituals with Bert Keightley as well, and “as a result of which they had got into some serious trouble.” (Perhaps they were influenced by Butler’s Solar Biology.) Blavatsky told Vittoria: “I had the greatest difficulty in extricating them from the mess into which they had gotten themselves.”[52] W.B. Yeats, who was witness to the drama, writes:

When I first began to frequent [Blavatsky’s] house, as I soon did very constantly, I noticed a handsome clever woman of the world there, who seemed certainly very much out of place, penitent though she thought herself. Presently there was much scandal and gossip, for the penitent was plainly entangled with two young men, who were expected to grow into ascetic sages. The scandal was so great that Madame Blavatsky had to call the penitent before her and to speak after this fashion, “We think that it is necessary to crush the animal nature; you should live in chastity in act and thought. Initiation is granted only to those who are entirely chaste,” and so to run on for some time. However, after some minutes in that vehement style, the penitent standing crushed and shamed before her, she had wound up, “I cannot permit you more than one.”[53]

The name of Mabel Collins disappeared from Lucifer beginning with the February 15, 1889. “No explanation was offered for this change, either in Lucifer, or by Miss Collins, who retired into privacy.”[54] Blavatsky told Vittoria that she asked Mabel to leave the Society because of her conduct with the Keightleys, going into detail about the nature of the liaison. According to Vittoria:

One day [Blavatsky] sent for me. “My dear,” she began, “I must ask you to give up your association with Mabel Collins.” I told her that I would do nothing of the kind […] I promptly told her that I would on no account give up my friendship with Mabel Collins until I myself found her an unfit association. [Blavatsky] shrugged her shoulders. “Then I am afraid I must ask you also to leave the Society.” “I shall certainly do so,” I answered, though not without regret, for I was a staunch believer in the faith; but I was furious. At once I sought out Mabel Collins, who, the moment she saw me laughed aloud. “The old lady’s been after you,” she said; and then, “I knew you’d get it.”[55]

When Vittoria told Mabel everything Blavatsky had said, she became enraged and threatened legal action for defamation of character. Years later Vittoria would give an account of this event to none other than Aleister Crowley, who writes: “At the critical moment of her mission, Madame Blavatsky had been most foully betrayed by Mabel Collins with the help, according to the stratagems and at the instigation of Vittoria, who not only justified, but boasted of her conduct.”[56]

COUES 1889

On April 16, 1889, just before the Convention of the American Section, Coues wrote a long letter to Blavatsky detailing his own prestige, the strength of his Gnostic Branch, and half-veiled threats. His purpose was to try to induce her to ask the American Theosophists to place him at their head.[57] He wrote another letter the following day (April 17, 1889) on the same subject, stating:

Do you know you are getting great discredit in this country and for what do you suppose? For being jealous of me! Can you imagine such flapdoodle? You are not moved by abuse, but you want to know how people think and what they say, and a great many are talking loudly and wildly, that your silence respecting my books in The Secret Doctrine, and the absence of my name from Lucifer (as well as from The Path) means that you are afraid of my growing power and will brook no rival so dangerously near the papal throne of Theosophy […] There is another queer thing. You have somehow got it stuck in your mind, that I put in The Chicago Tribune last year a caricature of the Master K. H. I had nothing whatever to do with the article, which was merely a newspaper skit, and the lithographed effusion was no more a Mahatmic document than this letter. It was simply a piece of newspaper wit. Judge is a good fellow and means well, and I like him for many things, especially his devotion to you and the masters and their Cause; but dabbling in occultism, especially on a Mahatmic altitude is dangerous except to an Adept!!! I am the humble servant of my Mahatma.[58]

It is probably not a coincidence that on April 18, Mabel wrote the following letter to Coues:

I feel I have a duty to write to you on a difficult and (to me) painful subject, and that I must not delay it any longer. You will remember writing to me to ask me who was the inspirer of Light on the Path. If you had not yourself been acquainted with Madame Blavatsky, I should despair of making you even understand my conduct. Of course I ought to have answered the letter without showing it to anyone else; but at that time I was both studying Madame Blavatsky and studying under her. I knew nothing then of the mysteries of the Theosophical Society, and I was puzzled why you should write to me in such a way. I took the letter to her; the result was that I wrote the answer at her dictation. I did not do this by her orders; I have never been under her orders. But I have done one or two things because she begged and implored me to; and this I did for that reason. So far as I can remember I wrote you that I had received Light on the Path from one of the Masters who guide Madame Blavatsky. I wish to ease my conscience now by saying that I wrote this from no knowledge of my own, and merely to please her; and that I now see I was very wrong in doing so. I ought further to state that Light on the Path was not to my knowledge inspired by anyone; but that I saw it written on the walls of a place I visit spiritually, (which is described in The Blossom and the Fruit)—there I read it and I wrote it down. I have myself never received proof of the existence of any Master; though I believe (as always) that the mahatmic force must exist.[59]

The American Convention met at the end of the same month. Professor Coues was not present. He was not elected President, or any other officer of the American Blavatsky did not cable the Convention as requested.[60] On April 30, 1889, Blavatsky wrote Coues from London, and listed, point by point, the various matters Coues mentioned in his letters, “in friendly, considerate, but severely plain language.”[61] Coues cabled Mabel on May 2, 1889, for permission to use her letter at his discretion. Mabel cabled him from London the following day saying: “Use my letter as you please.”[62] Coues subsequently had the letter published in the Religo-Philosophical Journal in May 1889.[63] The proprietor of said journal, John C. Bundy, was a member of Coues’s Gnostic T.S. [64] In his preface to Mabel’s letter in the journal, Coues writes:

In 1885 appeared a strange little book entitled: “Light on the Path: A treatise written for the personal use of those who are ignorant of the Eastern Wisdom, and who desire to enter within its influence. Written down by M. C. Fellow of the Theosophical Society.” The author is Mabel Collins, until lately one of the editors of Lucifer. The book is a gem of pure spirituality, and appears to me, as to many others, to symbolize much mystic truth. It has gone through numberless editions and is used by faithful Theosophists much as orthodox sinners use their prayer-book. This happened mainly because Light on the Path was supposed to have been dictated to Mrs. Collins by “Koot Hoomi,” or some other Hindu adept who held the Theosophical Society in the hollow of his masterly hand. I liked the little book so much that I wrote Mrs. Collins a letter, praising it and asking her about its real source. She promptly replied, in her own handwriting, to the effect that “Light on the Path” was inspired or dictated from the source above indicated. This was about four years ago; since which time nothing passed between Mrs. Collins and myself until yesterday, when I unexpectedly received the following letter. I was not surprised at the new light it threw on the pathway of the Theosophical Society, for late developments respecting that singular result of Madame Blavatsky’s now famous hoax left me nothing to wonder at.[65]

Coues then allied himself with a disenfranchised Theosophist from St. Louis named Michael Angelo Lane, and launched a similar campaign against Blavatsky in Britain by having Mabel’s letter published in the Spiritualist journal, Light.[66] Coues “proof” that Blavatsky was a fraud was predicated on Mabel’s unsigned and undated note which he claimed to have received in 1885. In actuality, Coues only succeeded in convicted himself of slander. In stating that he had received Mabel’s note in 1885, Coues inadvertently revealed that he was “building a case” against Blavatsky. The Gates Of Gold was not written until 1886 (and published early in 1887.) It was also well-known that The Idyll Of The White Lotus was written before Mabel ever met Blavatsky. Blavatsky stated:

The little book was published in the beginning of 1885, at a time when I was at Adyar and dangerously ill. In March I was hurried away from Madras by the doctors, brought to Naples, thence to Germany, and finally to Ostend. I came to London only on May 1st, 1887. Thus I had not set eyes on [Mabel Collins] from November 1884 to May 1887, nor did I have any correspondence with her. I heard of the existence and saw Light on the Path for the first time in the summer of 1886 when Mr. Arthur Gebhard gave a copy to me after his return from America.

AMERICA AND ENGLAND AGAIN

Vittoria states: “In 1889 I had occasion to sail for America in connection with certain business, and it was in February 1890 before I returned to England.”[67] It would seem that Louis Cremers re-married in February 1890 to a woman named Linda Vanzandt.[68] Perhaps Vittoria needed to sign some documents for divorce.

Southsea, 1890.

Vittoria arrived in England in early March. She made straight for her usual lodging-place at 21 Montague Street, off London’s Russell Square. Although worn out and tired, she was unable to sleep, her thoughts were in a turmoil over Mabel. She was so preoccupied that she went to Mabel’s new address in York Terrace, just behind Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum on Marylebone Road. When she arrived, the maid told her that Mabel was away in Soutshea, writing a new novel. [In 1890 Mabel published The Idyll of the White Lotus (the psychographical work that she began after the first visitation of the beings “dressed in peculiar garb.”)] Mabel’s maid gave Vittoria the address there, and the next day she took a train to visit her.

Vittoria was appalled at the contrast of splendor of York Terrace and the shabby building where Mabel resided in Southsea. An unkempt woman answered the door and took Vittoria to a poorly-furnished bedroom on the first floor. The embers in the fireplace suggested someone was recently there, but otherwise the room was empty.

Vittoria paced up and down to keep herself warm. She wished she had not come. Then she heard the front door open, the murmur of voices, one unmistakably belonging to Mabel’s, the other to a man. Then came the quite shutting of the door followed by footsteps hurriedly coming up the stairs. A moment later Mabel burst into the room in a flurry of embarrassment; or so it seemed.

“Well, Vittoria—so you’ve caught me at last. How are you?”

That was the first greeting. They neither kissed nor shook hands.

Mabel flung herself onto the unmade bed and settled herself in Eastern fashion, and lit a cigarette. It was over a year seen they last saw each other, and there was much on both sides to talk about. But Mabel rattled on about nothing in particular until she suddenly paused and regarded her closely.

“Do you remember an article in the Pall Mall about Rider Haggard’s ‘She?’” Mabel asked. “It was signed ‘D.O.,’ if you remember?”

Vittoria said that she remembered her mentioning the article to her in 1889, but she had never read it, and could not recall the signature of the writer.

“Do you remember that I told you I had written to the author care of the Gazette?”

“No, I can’t say that I do.”

“Well—I did write to him, and after some weeks received a reply. It was only a few lines saying that the writer was ill in hospital, but as soon as he was better, he would write and make an appointment, Again some weeks passed by before I heard anything and then a letter arrived from a Dr. D’Onston making an appointment—a marvelous man, Vittoria, a great magician who had wonderful magical secrets.” She paused to light another cigarette, for she was smoking furiously throughout the talk. Then she went on. “He’s here with me now—still very ill. I’m taking care of him—as soon as he is better, we are coming back to London, and we will all go into business together. The three of us.”

Vittoria offered no comment.

It required no powers of deduction to realize that D’Onston had been sent out while Mabel told Vittoria of theory association. In any case, the suggestion of tea was welcome and Vittoria gladly followed Mabel down the stairs. A fire and tea went right home, but her mention of the “marvelous man” and “great magician” meant nothing to Vittoria.

Having thawed over their tea, Vittoria tongue was loosened and she rattled on about her Paris trip, the nature of their business there, and her meeting with Sarah Bernhardt. She did full justice to the meal provided, and they were halfway through tea when there was the sound of a key grating in the lock of the front door.

“Here he is!” exclaimed Mabel.

Vittoria rose and pushed her chair nearer the wall to make room for the “marvelous man” whom she assumed would be glad of a hot cup of tea.

“Oh—you needn’t bother, Vittoria,” said Mabel casually, “he never eats.”

This statement struck Vittoria as very peculiar, but she had no time make any reply however, for by this time he had entered the room so quickly that Vittoria was surprised to find him there. Vittoria found herself looking up into the face of a tall, fair-haired man if unassuming appearance. A man at whom one would not look twice. He held a cap in one hand while under his arm was tucked—in true military fashion—a short cane. Vittoria was not duly impressed. To her there was nothing “marvelous” at all about this man, and yet there was an indefinable something.

“So this is Vittoria?” he remarked as he took Vittoria’s hand.

Vittoria nodded, noticing the pleasant and cultured tonality of the man’s voice.

“I have told her all about you,” said Mabel, “so there is no need for an introduction.”

D’Onston moved noiselessly over to an armchair in which he seated himself.

Vittoria busily sized up the man sitting opposite her, it was a habit of hers. Gentle; silent; someone who would remain calm during any crisis; tall; not an ounce of superfluous flesh upon him; military bearing unmistakable and a suggestion of strength and power; pale; a face with a queer pallor—not a particle of color anywhere; pink underlip; upper lip hidden by a fair moustache; fair hair—thinning on the sides but well-groomed about the head; teeth slightly discolored—probably from pipe-smoke; super-cleanliness; his clothes, though old and torn, appeared to suffer from assiduous brushing rather than wear and tear. The sum total of her estimate of the man was nil—absolutely nothing. “Perhaps it is because he ill,” thought Vittoria. “I wonder what is the matter with him…” The only thing remarkable about Dr. D’Onston was his pale blue eyes which. “They are the eyes which one might expect to find set in the face of a patient in the anemic ward of any hospital,” Vittoria thought. “There is not a vestige of life or sparkle in them.”[69]

D’Onston. [70]

POMPADOUR

Late March, 1890

“Good God, D’Onston,” Vittoria exclaimed. “Where on earth did you get those filthy-looking candles?”

“I made them,” he answered quietly.

“Made them?” Vittoria took another look at the candles. “I should think you did, I have never seen such grubby looking things in all my life. What are they made of?”

“It,” said D’Onston, breaking an extended silence, “is an experiment.”

“What,” said Vittoria, trying to lighten the mood, “going into the candle business now?”

“No.”

Vittoria knocked her shin into the black-enameled deed-box in D’Onston’s room, as she had done on several occasions.

“What on earth have you got in that box?”

“A few first editions, Vittoria,” he replied. “Books are very heavy, you know. I also keep some of my private papers in it.”[71]

BAKER STREET

Mid-April, 1890

One morning Mabel entered the office in Baker Street, and after a nervous glance around the place whispered, “Where is he?”

“Out,” Vittoria replied. “Why—do you want him?”

She shuddered. In her eyes was the shadow of a haunting fear.

“Vittoria,” said Mabel, “I believe D’Onston is Jack the Ripper.”

Vittoria looked at her in astonishment. “You must be joking,” said Vittoria, but she could tell that Mabel was serious. “What on earth makes you say that?”

“Something he said to me, Vittoria. Something he showed me. I cannot even tell you—but i know Vittoria—and I am afraid.”

There was no doubt about that. Fear reflected in every expression of her eyes and in every shrinking gesture. But Mabel did not elaborate, nor confide in Cremers, as she typically did. Cremers thought no more of the topic—reasoning that the lovers probably had some misunderstanding, and that the ordeal would sort itself out.[72]

ALONE WITH D’ONSTON

Late-April, 1890

Vittoria’s eyes lingered on the black-enameled deed-box in D’Onston’s room as he finished telling his story.

“What happened to your wife D’Onston?” Vittoria asked.

They were chatting together about nothing in particular when, in a chance remark, D’Onston mentioned he had a wife. This was the first time Vittoria ever heard if the existence if such person. She had assumed he was a hard-and-fast bachelor, impervious to any romantic or emotional feeling. Cremer picked up her ears, but as D’Onston made no further reference to the lady, she felt compelled to ask.

Baker Street, 1890.

The question produced a change in the man. D’Onston, who was lounging in his chair, quickly rose to his feet, and began pacing the room. By some ocular necromancy, D’Onston’s eyes showed signs of life, a hint of restless unease. He stalked the room, back and forth, until passed the desk where Vittoria was seated, and, suddenly pausing in his stride, faced her. Staring at Vittoria, D’Onston pantomimed a dramatic gesture across his throat with a single finger, while simultaneously emitting an otherworldly, guttural groan. He then resumed his restless pacing. Cremers watched as D’Onston slowly regained control of himself, and remembered the fear which Mabel had unburdened. “My God!” thought Vittoria. “D’Onston is Jack the Ripper!”

One could not murder with impunity without arousing some suspicion, Vittoria thought—and yet Jack the Ripper had. He murdered woman after woman, in fact, and gotten away with it.

At the very first opportunity Vittoria told Mabel of the incident in the office, and she nodded her head.

“Yes, Vittoria,” she said, “I know he has been married, but he will never talk about his wife. I did not know that he had killed her. He simply said that he had disappeared suddenly—vanished completely, and he had not heard of her for years.”

It struck Vittoria how readily and without surprise that Mabel accepted the idea that her lover had murdered his wife.

“Vittoria,” said Mabel, “I am terrified of him. I know he is Jack the Ripper and I want to get away from him, but I am afraid. He has such powers—I wish he would leave me alone—go away—do anything—only leave me alone. I would give him money—anything—if only I could be free of him!”[73]

THE SPECTER OF THE RIPPER

In July 1890, the Westminster Gazette raised the specter of the Ripper once more; reporting that the police had gained advance information about the killer’s intentions. A new cycle of horror was about to begin. Vittoria read this and decided to mention it to D’Onston to gauge his reaction. But he was one step ahead of her while ridiculing the report. Then his mood changed abruptly.

“There will be no more murders.” He walked across to

Vittoria’s desk and leaning over it, stared down and said. “Did I ever tell you that I knew Jack the Ripper?”

Vittoria felt a cold shudder run through her. Anxious to gain time to recover herself, she bent down and opened a drawer. “Where the deuce did I put the ruler?” she muttered to herself, and continued to fumble in the drawer. But D’Onston would not be denied, for still leaning over the desk he repeated: :Did I ever tell you that I knew Jack the ripper?”

Cremers was now disturbed and uneasy but she struggled to stay calm and gave a non-committal reply. At that, D’Onston began to pace up and down the room. Vittoria remembered when he’d mimed the throat-cutting of his wife. And then, in a quiet voice D’Onston said:

“You know that when Mabel first wrote me, I was in the hospital? That was just after the last of the murders, Vittoria,” he went on, “and you can take it from me that there were no more murders after thar one in Miller’s Court on November 9.”

He paused for a moment, came close to Vittoria, and then remarked that he was living in the Whitechapel neighborhood at the time. He went on to say that he was taken seriously ill and had to enter the hospital. Something to do with the “Chinese slug,” was what he told Vittoria.

“It was there that I met him, Vittoria. He was one of the surgeons who operated, and of course when he learned that I had also been a doctor he became more interested in my case, and we became very chummy.

“Naturally we talked about the murders because they were the one topic of conversation. One night he opened up and confessed that he was Jack the Ripper. At first, I did not believe him, but when he began to describe just how he had carried out the crimes I realized that he was speaking from actual knowledge, and was speaking the truth.”

D’Onston rose from his chair and recommenced his restless pacing up and down the room. Then once more he paused and stood before Vittoria.

“At the inquest, Vittoria, it was suggested that the women had been murdered by a left-handed man, or at any rate with the left hand.” He smiled in derision. “It just shows that they could not see an inch before their noses, Vittoria. My surgeon friend explained exactly how the medical witnesses fell into this error. He also told me that he always selected the place where he intended to murder the women. It was for a very special reason, Vittoria, which you would not understand. He took the Whitechapel Road as a sort of base for his operations, and made several journeys before deciding on the spots best suited to fit in with his scheme of things. Then, having got his victims to these particular places, he maneuvered to get behind them.”

At this point D’Onston paused for some seconds which seemed like hours to Vittoria. He seemed as though he were reliving something that had happened some time before. Then he spoke again.

“All those doctor fellows took it for granted that Jack the Ripper was standing in front of the women when he drew the knife across their throats,” he said, and paused before continuing, “but he wasn’t, Vittoria—he wasn’t. He was standing behind them like this.” As he spoke D’Onston crossed over and stood behind Vittoria’s chair. She felt an uncanny expectant feeling as she sensed him standing there; she could almost feel a knife at her throat.

But when he was talking again, quite calmly, yet with deadly earnestness. “It was quite simple really,” came his voice from behind as he reached round and placed his left hand over her mouth and nose, pulling back her head back. Vittoria could scarcely breathe so firm was his grip. Then his other arm reached around her neck from the right, and again he spoke.

“You see, Vittoria,” he said, “this arm (waving his right arm before her eyes) would be quite free, and all my friend had to do was make one quick slash with his knife and it was all over before they could utter a sound.”[74]

As he said this, D’Onston’s arm relaxed and he withdrew if from Vittoria’s neck/ At the same time he lifted his left hand from her nose and mouth, and she drew a deep and grateful breath.

“At the inquests, Vittoria, these same doctors made a point of mentioning that the women did not fall but appeared to have lain down. This is about the only thing right about the evidence. They did not fall. My friend did lay them down, and then—when they were on the ground, he carried out the mutilations—so.”

As he spoke, he came round to the front of Vittoria and a made a gesture with his thumb in the motion of a downward triangle, such as she had often seen him making upon the door of his room on more than one occasion. Meanwhile D’Onston was continuing his narrative of what, he said, happened at the scene of the crimes.

“Everybody, Vittoria, including the police were on the look-out for a man with bloodstained clothing,” he said, “but of course, killing the women from behind, my doctor friend avoided this, as their bodies offered some sort of protection. Had he been in front of them his clothes must have been drenched with blood. Once or twice, he told me, he found a spot or two, but soon removed them.”

D’Onston’s revelations were made in a detached fashion; a mood which persisted, even when he reveled in the details of the gory knife-work.

For the first time, Vittoria learned how, in two instances, the murderer, after mutilating the bodies, took away the uterus; the mere mention of this fact horrified her, but she could see the lifeless grin D’Onston gave when relating this part of the story. She was still more horrified when D’Onston continued to say:

“He tucked these organs in the space between his shirt and tie, Vittoria,” going through the motions as he did so.

“Good God!” Vittoria shuddered, remembering the black tin-box in D’Onston’s room containing ties with their stained underparts. “Who but the murderer himself,” thought Vittoria, “could possibly know the things D’Onston had told me?” It was borne in her mind that this alleged “doctor friend” was nothing more than a figment in D’Onston’s imagination, invented to conceal his own identity with Jack the Ripper. She was now convinced, beyond all doubt, that the man standing before her was in fact the Whitechapel murderer.

During the latter part of D’Onston’s narrative Vittoria was careful to intently watch him. At the end he looked intently at her to see how she was taking it. Cremers endeavored to assume a calm demeanor.

“But what did your friend want, D’Onston?” said Vittoria, trying to break the spell, as it were. “What was he after?” By this time, Vittoria was more than ever anxious to get right into the mind of the man she now regarded as a self-confessed murderer. She was puzzled at the idea of this apparently serene-minded cultured person, as she D’Onston to be, being guilty of the horrors he had just described to her without the quiver of an eyelid. She had not read about the crimes at the time, and it was not until this moment, and from D’Onston himself, that she learned the nature of the atrocities. Hence her desire to discover the motive which impelled him to such gruesome crimes. Why had he murdered so many women, and what was the object of the ghastly mutilations inflicted upon his victims after death?

There was no thought in her mind of any magical background to the murders. She knew little of magic beyond Mabel’s description of D’Onston as a “great magician.”

“But what did he want?” It was the recollection of the ties, and his explanation of how they came to be stained with blood, which prompted Vittoria to ask. “What was he after?”

D’Onston was not to be drawn, however. He simply shrugged his shoulders. “He did tell me, Vittoria, but you would not understand.”

Vittoria knew that it would be fruitless to pursue the question. “But didn’t you ever tell the police?”

“Yes,” said D’Onston. “I told them alright, but by the time they went to arrest him he had gone. You know, Vittoria, the police were awful duffers. Why, they had me in for questioning on two occasions, but of course I was easily able to satisfy them and they had to let me go.”

Vittoria proceeded to ask him a question here and there, giving no inkling of her suspicions. Yet, all the time she was paving the way towards a scheme, whereby she hoped to persuade him to set down in fuller detail (with the object of newspaper publication) the story of the mysterious “doctor friend.” Vittoria knew that D’Onston was invariably hard up, and not that Mabel had broken with him, and there was little income coming from the Cosmetique Company, Vittoria felt sure he must be worse off than ever.

Suddenly she put her scheme to him directly, pretending enthusiasm for the idea as though it had just struck her.

“You know D’Onston,” said Vittoria, “that’s one of the most amazing stories I have ever heard. There’s money in it. Why don’t you write it up for the Pall Mall Gazette? You are well in with Stead, and he would jump at it.”

“Oh I don’t know…”

“It would create a sensation,” Vittoria said. “It would pave the way for stories in other newspapers.”

D’Onston appeared reluctant, but Vittoria was determined to make him set down in black and white the terrible stories he had told her. She got out pen and paper and placed them before him. D’Onston sat down and began to scribble off three or four pages of preamble, handing them to her to read as she did so. The sweat simply poured from him as he wrote, and he was obviously labouring under some great emotional strain as he scribbled away. Vittoria had never before seen him so much affected. Suddenly he rose to his feet, roughly pushed back his chair and then, without a trace of turmoil which had been so pronounced a few seconds before he turned to Cremers and said: “I’ll finish it tommorow, Vittoria, and take it straight round to W.T. Stead in the morning.”

Vittoria knew full well that he would do no such thing. The moment had passed. His excuse was simply subterfuge to escape writing the story, Vittoria realized he never intended to write it, but had been forced to fall in with her suggestion in order to lull any possible suspicions.[75]

SO MABEL’S GONE?

“So Mabel’s gone?” was all D’Onston said.

He did not mention her name again for several days.

One afternoon D’Onston drifted into the office in his usual soundless way, and approached Vittoria, who was sorting through some papers. He perched himself on her table and gazed at her. The Pompadour Cosmetique Company, at this time, was not in flourishing condition. Naturally, both D’Onston and Mabel were very interested had lost interest in it. Vittoria decided to wind things up and leave town for a bit, which she explained to D’Onston.

“I quite understand, Vittoria,” said D’Onston. In a dispassionate tone, he then disclosed his knowledge of intimate details relating to Vittoria and Mabel. Vittoria was very angry at this, for D’Onston could only have derived the particulars mentioned from Mabel herself.

That night Vittoria wrote to Mabel in Scarborough, repeating what D’Onston had told her. She asked Mabel for any reasonable explanation for her conduct, and informed her that if none was forthcoming then their friendship must cease.

Vittoria was hopeful that she would be able to justify her breach of confidence in some way, and awaited her reply with some little anxiety. A day or so later, she received a reply from Mabel. In the letter she simply said that she “quite understood.” There was not a word of apology or explanation, no denial no excuse; nothing but the acknowledgment that she “quite understood.”

It was a sad moment for Vittoria and she felt a blaze of anger against D’Onston. She called him into the office and told him that he was a swine to have betrayed a woman who had been so kind to him. But he simply gave his irritatingly expressionless smile. It was this attitude that filled Vittoria with such disgust, that, in her determination to discover who and what he was, she resorted to a course which, otherwise she would never have entertained. She fully realized that in other circumstances it would have been a “low-down” thing to do; but, his treatment of Mabel seemed at the time, to justify her next course of action.

She recalled D’Onston’s black box, and the private papers inside. Perhaps they contained clues to D’Onston’s true identity. From time to time when he went out, Vittoria entered his room by means of an old key which she found on an old bunch she always kept. She tried all the smaller keys on this same bunch on the two locks which the box secured. They did not fit. She went ti another neighborhood and scoured second-hand shops for old keys, and at length discovered one that fit.

Armed with this, Vittoria seized the opportunity when D’Onston was out, and entered his room. In a few minutes she was on her knees beside the open box, carefully lifting from it the books which he mentioned so that she could replace them exactly as she found them. She noticed they were all to do with Magic, one of them being written in French, but, having no particular interest in the books, did not take note of any of the authors. It was the private papers that intrigued her. But there was not a single paper to be found. Nothing that is, but a few ready-made black ties, the kind which D’Onston always wore.

Vittoria was disappointed with the result of her burglary. She had hoped for something more informative than those somber articles of men’s wear.

“Why you are a grubby-looking specimen,” she said, lifting one out of the box.

She was just about to replace it when something caught her eye. On the underside of the flowing end of the tie, and also at the back of the knot, she saw a dull sort of stain. She examined it more closely and discovered that where the stain was, thew tie was quite hard as though something had congealed upon it, She picked up another one, and found similar stains in similar places. She repeated this examination several times with several ties, and in each case found similar stains. Vittoria was baffled by the discovery. She could not imagine what the stains could be; nor how they came to be in such a peculiar position; above all—why did D’Onston keep the filthy, dirty things which he could not wear again anyway?[76]

TAU-TRIADELTA

Mabel and Vittoria were certain that D’Onston was not his real name.

“I have tried all manner of ways to find out who he is,” said Mabel. “I have tried to trap him into betraying himself. But he is too damned clever, Vittoria—too cunning.”[77]

“All reports about me emanating from Assad Farras, a dismissed interpreter, false. If made public, stop them. Sending necessary paper.”[78]

James Jameson.[80]

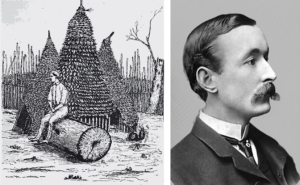

D’Onston brought Vittoria his article for the November 1890, issue of Lucifer. It was called “African Magic,” and signed Tau-Triadelta.[81] Perhaps D’Onston was just capitalizing on the sensational news of the day. In early November 1890, the headlines stated that James Jameson had paid a slaver to witness a cannibalistic act while on the Stanley Expedition in Africa.[82] A refutation was quickly published by the Jameson family, but the tantalizing details were fodder for the press.[83]

“Why, D’Onston,” said Vittoria, “what a funny way of signing yourself. Why don’t you sign your name?”

Tautriadelta.[84]

“That is my own name.”

“Tautriadelta?” Vittoria repeated. “But what does it all mean? It seems so strange to me.”

“Yes, Vittoria,” said D’Onston. “A strange signature indeed, but one that means a devil of a lot if you only knew.” He smiled a slow inscrutable smile without a trace of mirth. “A devil of a lot!”

“But what does it stand for?”

“Before the Captivity, the Hebrew Tau was always shown in the form of a Cross,” D’Onston explained. “It was the last letter of the sacred alphabet. Tria is the Greek for three, while Delta is the greek letter D which is written in the form of a triangle. So the completed word signifies ‘Cross-Three-Triangles.’” He paused for a minute as though reflecting. “And Vittoria,” he went on, “there are lots of people who would be interested to know why I use that signature. In fact, the knowledge would create quite a sensation.” And then, as though in defiance, “But they will never find out, Vittoria. Never.”[85]

Mabel and Cremers met for the last time in the summer of 1891.[86] Mabel tired of D’Onston, but feared getting rid of him because he had a bundle of compromising letters written by her. To put Mabel’s mind at ease, Vittoria offered to steal them from D’Onston. They suspected the letters to be in his bedroom, in a tin uniform case which he kept under the bed attached with cords. Neither Vittoria nor Mabel had ever seen this case open. Vittoria tricked D’Onston to leave his lodging with a forged telegram. She then entered the room, where she retrieved the box from under the bed. The box was light, to her surprise, as if it were empty. She picked the lock to open it, but found no letters. Instead, there were seven white evening dress ties. They were all stiff, and black, and with clotted blood.[87]

SOURCES:

[1] Blavatsky, H.P. “To The Editor Of ‘Light.’” Light. Vol. IX, No. 440. (June 8, 1889): 277-278.

[2] Coues, Elliott. “Attention, Theosophists!” Religio-Philosophical Journal Vol. XLVI., No. 12 (May 11, 1889): 5.

[3] M.C. “Some Psychic Experiences.” Broad Views. Vol. I, No. 5 (May 1904): 432-440; De Steiger. Isabelle. Memorabilia: Reminiscences Of A Woman Artist And Writer. Rider & Co. London, England. (1927): 241-251; Khandalavala, N. D. “Madame H.P. Blavatsky as I Knew Her.” The Theosophist. Vol. L, No. 9. (June 1929): 213-222; Lane, A.T. Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders, Volume I. Greenwood Publishing Group. Westport, Connecticut. (1995): 277.

[4] England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007. General Register Office; United Kingdom; Volume: 3a; Page: 1312. General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England: General Register Office.

[5] Ryan, Hugh. When Brooklyn Was Queer. St. Martin’s Publishing Group. New York, New York. (2019): 65-66.

[6] “A Hundred Thousand.” The Buffalo Commercial. (Buffalo, New York) February 1, 1888.

[7] Ancestry.com. Russia, Select Births and Baptisms, 1755-1917 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[8] “Ordained To A Pastor’s Work.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 11, 1884.

[9] “A Russian Nobleman’s Trouble.” The Memphis Avalanche. (Memphis, Tennessee) February 2, 1888.

[10] “A Russian Nobleman’s Trouble.” The Memphis Avalanche. (Memphis, Tennessee) February 2, 1888.

[11] Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C. Year: 1880; Census Place: New York City, New York, New York; Roll: 874; Page: 528C; Enumeration District: 162. [The eldest daughter was also named Harriett but seems to have gone by the name “Minnie.”] New York, State Census, 1905. Population Schedules . Various County Clerk Offices, New York. New York State Archives; Albany, New York; State Population Census Schedules, 1905; Election District: A.D. 19 E.D. 06; City: Manhattan; County: New York; Page: 21.

[12] Harris, Melvin. The True Face Of Jack The Ripper. Michael O’Mara Books Limited. London, England. (1994): 46-47.

[13] Casal, Mary. Stone Wall: An Autobiography. Eyncourt Press. Chicago, Illinois. (1930): 178-180; Crowley, Aleister. [Edited by Kenneth Grant & John Symonds.] The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Arkana/Penguin. London, England. (1988): 690-692; Ryan, Hugh. When Brooklyn Was Queer. St. Martin’s Publishing Group. New York, New York. (2019): 65-66.

[14] “A Terrible Charge.” The Standard Union. (Brooklyn, New York) December 3, 1887.

[15] Keightley, Archibald. “Reminiscences of H.P. Blavatsky.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. VIII, No. 2 (October 1910): 109-122.

[16] Cleather, Alice Leighton. H. P. Blavatsky As I Knew Her. Thacker, Spink & Co. Calcutta, India. (1923): 2; Farnell, Kim. Mystical Vampire: The Life and Works of Mabel Collins. Mandrake. Oxford, England. (2005): 60-80.

[17] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3482. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Alice Leighton Cleather. [11/3/1885]

[18] Cleather, Alice Leighton. H. P. Blavatsky As I Knew Her. Thacker, Spink & Co. Calcutta, India. (1923): 2.

[19] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2994. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Plato E. Draculi. Corfu. (8/31/1884); Draculi, Plato E. “Inter-Planetary Soul-Communion.” Light. Vol. VII, No. 361. (December 3, 1887): 569.

[20] “The Cause In Greece.” Justice. (London, England) November 16, 1889.

[21] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1950. The Cunningham Press. Los Angeles, California. (1951): 91.

[22] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2923. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) Elliot Coues.

[23] Allen, J.A. Biographical Memoir of Elliott Coues 1842-1899. National Academy of Sciences. Washington, D.C. (1909): 399; 423; [Letter: William Quan Judge to Henry S. Olcott, April 27, 1886] Judge, William Quan, and A. L. Conger. Practical Occultism. Theosophical University Press. Pasadena, California. (1951.)

[24] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. I, No. 6 (September 1886): 191-192.

[25] Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part III: Letter Dated 19 March 1887” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 4 (October 1994): 125-127.

[26] Gomes, Michael. “The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky to W.Q. Judge: Part V: Letter Dated Sept. 15, 1887, and Part VI: Letter Dated Sept. 27, 1887” Theosophical History. Vol. V, No. 6 (April 1995): 204-207.

[27] Coues, Elliott. “Attention, Theosophists!” Religio-Philosophical Journal. Vol. XLVI., No. 12 (May 11, 1889): 5.

[28] Coues, Elliott. “Through The ‘Gates Of Gold.’” Religio-Philosophical Journal. Vol. XLVI., No. 15 (June 1, 1889): 5.

[29] “A Terrible Charge.” The Standard Union. (Brooklyn, New York) December 3, 1887.

[30] “A Hundred Thousand.” The Buffalo Commercial. (Buffalo, New York) February 1, 1888.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4297. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Vittoria Cremers. (12/24/1887.)

[33] “Bogus Miracles Exposed.” The Sun. (New York, New York.) December 25, 1887.

[34] “Blavatsky’s Miracles.” The Indianapolis Journal. (Indianapolis, Indiana) May 4, 1896.

[35] “News Summary.” The Evening World. (New York, New York) April 9, 1888.

[36] “A Line From Koot Hoomi.” The Chicago Tribune. (Chicago, Illinois) May 5, 1888.

[37] Ibid.

[38] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 187-188.

[39] Ibid: 187-188.

[40] Ibid: 188-189.

[41] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 46-47.

[42] One Who Thinks He Knows. “The Whitechapel Demon’s Nationality: And Why He Committed The Murders.” The Pall Mall Gazette (London, England) December 1, 1888.

[43] “Tittle Tattle for The Tea Table.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) December 3, 1888.

[44] Stead, W.T. “Our Gallery Of Borderlanders: A Modern Magician: An Autobiography.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 2. (April 1896): 139-156.

[45] Saraswati, Bhaskara Nand. “Some Customs Of Aryavarta.” Oriental Department Papers. No. I. (January 1891): 1-9.

[46] Blavatsky, H.P. “Dialogues Between Two Editors” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 16. (December 15, 1888): 328-333.

[47] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 49.

[48] D’Onston, Roslyn. “The Real Origins Of She.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) January 3, 1889.

[49] D’Onston, Roslyn. “What I Know Of Obeeyahism.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) February 15, 1889.

[50] “Blavatsky’s Miracles.” The Indianapolis Journal. (Indianapolis, Indiana) May 4, 1896.

[51] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1950. The Cunningham Press. Los Angeles, California. (1951): 91.

[52] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 68-69.

[53] Yeats, William Butler. Four Years. The Cuala Press. Dublin, Ireland. (1921): 74-75.

[54] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1950. The Cunningham Press. Los Angeles, California. (1951): 91.

[55] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 68-69.

[56] Crowley, Aleister. (eds) Grant, Kenneth; Symonds, John. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Arkana/Penguin. London, England. (1988): 690-692.

[57] Coues writes: “You appear to have been misinformed or uninformed respecting the Gnostic and its Branches, as well as my own work in your behalf. Both in numbers and in quality of its membership, the Gnostic is unquestionably the leading Branch of the T.S. in the country. Its members are for the most part of a high, refined, educated, and influential class in society, in science and before the world, and most of them are indefatigable in working for the cause to which your own great and noble life is devoted. I am satisfied that if you would do your part to give my Gnostics their just dues and recognition, they and I can lift Theosophy clear of the mud which has been thrown upon it and set your own self in a proper light before the world. We all feel keenly the abuse and persecution to which you have been subjected, and anxious to do you full justice and honor. But they are unanimously dissatisfied with the way the society is run at present, and they wonder where your intuition can be, that you fail to see where your obvious advantage lies, in not strengthening and holding up the hands of their representative man […] Be wise now and be warned in time; you are a very great woman, who should be quick to see that this is no ordinary occasion . I tell you frankly, it is possible that all this prestige, social and personal and professional influence, scientific attainment, and public interest, can be thrown on the side of the T.S., as at present constituted, or can be switched off on a new track aside from the old lines. If you cannot see this, and understand it, and act accordingly, there is nothing more for me to say, and I must presume that you do not care for my people. Judge and I came to a fair understanding once, and I was carrying out our agreement in good faith, and all was smooth, when something or other, affecting the question of the Presidency, interfered, and since then there has been nothing but friction and misunderstanding in the ‘Esoteric’ T.S.—which you know consisted of yourself, myself, and Judge and your issue of a new and different ‘esoteric’ manifesto did not mend matters. Now be wise and politic. The T.S. in America is at present a headless monstrosity: it must have a visible, official head to represent its real, invisible source. You know whom the majority of the F.T.S. have desired to put forward as their representative theosophist in America. It is only necessary for you to cable the Chicago Convention, to elect him president. Weigh these words well; pause, consider, reflect, and act. ‘If ‘twere well done, ‘twere well done quickly.’”[The Theosophical Movement 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 190-191.]

[58] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 192.

[59] Coues, Elliott. “Attention, Theosophists!” Religio-Philosophical Journal Vol. XLVI., No. 12 (May 11, 1889): 5.

[60] Coues, Elliott. “Attention, Theosophists!” Religio-Philosophical Journal Vol. XLVI., No. 12 (May 11, 1889): 5.

[61] Blavatsky writes: “Dear Doctor Coues: I have received your two letters and read them as they stand and also between the lines and therefore, I mean to be as frank with you as you are frank with me. I will take your two letters point by point […] If you had nothing to do with The Chicago Tribune article ([though] you must have influence with your own nephew) then why did you not contradict it, then and there? […] I know nothing about the number of messages you may have received from Masters through Judge, whom I would never believe capable of it, or anyone else […] You speak of my seals on those letters […] Where did they get this? From Judge, from me or from you? It could hardly have been any except one of us three […] Your wise advice that such Mahatma messages should be confined to one channel, ‘the only genuine and original H.P.B. your friend,’ was anticipated by Mahatma K. H. in so many words. Then why do you kick against that? You speak of your Mahatma; then why don’t you send letters in his name instead of those of my Master and Mahatma K. H. That would settle all the difficulties and there would be no quarrel […] What you have learned through me, I know, and do not want to know beyond. You may obey or disobey your Master as much as you like, if you know him to exist outside of your psychic visions. As to mine, every man devoid of all psychic powers can see him, since he is a living man. I wish he could be yours, for then, my dearest Dr., you would be spiritually a better man and less a skeptical one than you are. You speak of your eagerness ‘to defend and help a woman who has been sadly persecuted, because misunderstood.’ Permit me to say to you for the last time that no bitterest enemy of mine has ever misunderstood me as you do.” [The Theosophical Movement 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 192-194.]

[62] Coues, Elliott. “Attention, Theosophists!” Religio-Philosophical Journal. Vol. XLVI., No. 12 (May 11, 1889): 5.

[63] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1950. The Cunningham Press. Los Angeles, California. (1951): 89.

[64] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 3368. (Website file: 1B:1885-1890) John C. Bundy.

[65] Coues, Elliott. “Attention, Theosophists!” Religio-Philosophical Journal. Vol. XLVI., No. 12 (May 11, 1889): 5.

[66] “’Light On The Path.” Light. Vol. IX, No. 439. (June 1, 1889): 264.

[67] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 47.

[68] Ancestry.com. New York State, Marriage Index, 1881-1967 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2017. [New York State Department of Health; Albany, NY, USA; New York State Marriage Index.]

[69] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 47-50.

[70] Stead, W.T. “Our Gallery Of Borderlanders: A Modern Magician: An Autobiography.” Borderland. Vol. III, No. 2. (April 1896): 139-156.

[71] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 67, 77.

[72] Ibid: 71-72.

[73] Ibid: 72-73, 77.

[74] Ibid: 79-84..

[75] Ibid: 79-84.

[76] Ibid: 76-78.

[77] Ibid: 77.

[78] “The Cannibal Story.” The Bolton Evening News. (Lancashire, England) November 12, 1890.

[79] Tau-Triadelta. “African Magic.” Lucifer. Vol.VII No. 39. (November 15,1890): 231-235.

[80] Jameson, James S. The Story Of The Rear Column Of The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. R.H. Porter. London, England. (1890): Frontispiece, 309.

[81] Tau-Triadelta. “African Magic.” Lucifer. Vol. VII No. 39. (November 15,1890): 231-235.

[82] “The Cannibal Story.” The Bolton Evening News. (Lancashire, England) November 12, 1890.

[83] Jameson, James S. The Story Of The Rear Column Of The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. R.H. Porter. London, England. (1890): xv-xxvi.

[84] “African Wizards Make Snakes Appear In Fire.” The World. (New York, New York) May 24, 1896.

[85] Harris, True Face Of Jack The Ripper: 65-66.

[86] Farnell, Kim. Mystical Vampire: The Life And Work Of Mabel Collins. Mandrake. Oxford, England. (2005): 114.

[87] Crowley, Aleister. [Edited by Kenneth Grant & John Symonds.] The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Arkana/Penguin. London, England. (1988): 690-692.