UNION OF HEARTS

ACT II.

II.

(Maud’s story continued from “The Servant of the Queen.”)

⸻

Houses of Parliament from the Thames, London, England.[1]

“Fill in a form with the name of the M.P. you wish to see,” the policeman politely told Maud in St. Stephen’s Hall. “Your name, your address, and your business.”

Maud hesitated about the “business,” before finally scribbling “important.” She wondered if that might be a slight exaggeration.

“Fighting the British Empire was important, after all,” Maud reasoned, “even though I only want to be told how.”

Houses of Parliament, St. Stephen’s Hall (Interior), London, England.[2]

Maud passed the time waiting by studying the groups of people standing around the barriers, who, like herself, were waiting to meet some M.P. They were mixed lot—there were some fashionable women, but mostly unassuming country folk (some evidently on delegations, others stood alone or paced back and forth. Young men with portfolios tucked under their arms darted through; secretaries or officials, obviously, for the policemen let them pass without interrogation.

“Are you interested in the Suffrage movement, dear?” an old woman asked Maud, while handing her leaflets.

“I know little about it—but I quite agree that women should vote,” said Maud, taking the leaflets. “Does one generally have to wait so long to see a member of parliament?”

“How long have you been waiting?” the old woman asked.

“About a quarter of an hour.”

“That is nothing, I have often waited the whole afternoon and not seen the man I wanted. They do it on purpose when they don’t want to see you. Of course, sometimes there are divisions, and they can’t come.”

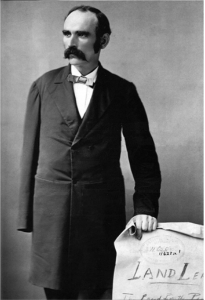

Michael Davitt.

Just then Maud caught sight of slender, one-armed man standing inside the barrier.

“Mr. Michael Davitt,” the policeman called out.

Maud pushed her way forward. Davitt asked her inside the barrier, and they sat down on one of the stone seats at the side.

“I want to work for Ireland, and I am entirely free,” said Maud. “I have been revolted by seeing the conduct of landowners in Ireland. I know many people in France—and a few in Russia—who are sympathetic with Ireland. I have come to you, Mr. Davitt, to know how l can help.”

“I have been in Paris lately on work connected with the Times Commission,” Davitt said. “Publicity abroad might be useful—the English Government is trying to identify the Irish Party with crime and outrage.”

“But that doesn’t matter,” said Maud, unwisely. “With England’s treatment of Ireland, whatever an Irishman may do in retaliation, should not be considered a crime. What England calls outrages are acts of war, and retaliation is perfectly justified. Foreigners could be made to see things in that light!”

“No,” said Davitt. “Outrages are stupid. They will defeat Home Rule and on Home Rule the future of the thousands of evicted tenants depends. The English Government would invent outrages to create disunion and turn the masses of the English people against Home Rule and destroy the Union of Hearts.”

It was the first time Maud heard the expression, “Union of Hearts.” It did not appeal to her. She noticed a coat of melancholy cover Davitt’s keen and kindly eyes when she spoke of condoning outrages. Davitt’s family had been evicted when he was a child. He was raised in England and worked among the English in Lancashire (a people nearly as poor and exploited as the Irish.) Somehow, he maintained a certain faith in the English, even during the years he suffered imprisonment at the hands of their Government.

Davitt abruptly stood up and offered Maud a ticket for the Ladies’ Gallery.

Maud accepted the ticket, but very soon got bored sitting in the gallery listening to Joe Biggar reading out reports from Blue Books to empty benches in his heavy Northern accent. She failed at obtaining any useful advice from Davitt as to how she should work for Irish freedom, so she decided she would have to find the work by herself in Ireland.

~

Maud was almost too afraid to return to Dublin. It seemed lonely now without her father. Happily, she accepted an invitation from her old friend, Ida Jameson, to stay with her in her home, “Airfield.”[3] Ida’s father, Andrew Jameson, loved the “golden fluid” from his famous vats so much, that he had “ceased to count among the living,” and was only occasionally visible on the grounds of Airfield in his wheelchair—attended by a nurse.

Workers at the Jameson distillery in Dublin, Ireland.

A certain sadness was palpable. The family received word a week earlier, that James Jameson, Ida’s brother, had died in African during the Stanley Expedition. Shortly before his death, James sent a cryptic telegraph to his wife which read:

All reports about me emanating from Assad Farras, a dismissed interpreter, false. If made public, stop them. Sending necessary paper.[4]

Ida’s intuition told her that something unsettling surrounded the death of her brother, but more than that she could not say. Ida was a “strange girl,” with a beautiful voice, and “curious psychic faculties.” An interest in spirits ran in Jameson blood, as her niece, James’s daughter, Isabel Agnes Jameson, was a member of the Theosophical Society.[5]

A telepathic bond existed between Ida and Maud. Ida could see things invisible to most, and Maud shared a little of that same gift—it formed the basis of their childhood friendship, for Ida knew that Maud was not lying when she spoke of the shadow woman with the sad eyes that hovered by her bed. Likewise, Maud knew that Ida really had seen the “big black dog, with eyes of fire,” that haunted Donnybrook Road, and frightened all the servants. Acclimated to the supernatural, the girls were never afraid of those things—only afraid of being laughed at for speaking of them.

~

Ida had just become engaged to the French Vice-Consul, Robert Boeufvé, but her family were against the marriage, and this complication absorbed most of her time. Maud, however, was fully committed. One of the first things she did after arriving in Dublin was join the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language.[6]

In the rose garden of Airfield, Maud told Ida that she had come back to work for Ireland’s freedom, and about her disappointing interview with Michael Davitt. Though her family were Unionists, Ida was eager to help. That afternoon, Ida went into town and ordered two gold rings with Éire (Irish for “Ireland”) engraved on them. “We must both always wear them,” Ida told Maud. “I have arranged for us to go to tea tomorrow with a student at Trinity College named Charles Hubert Oldham. He is a Protestant Home-Ruler, and I think he is engaged in important work for Ireland. He is the secretary for the Contemporary Club.”

Oldham was amused, for Ida and Maud were “both so ignorant.” Nevertheless, he was a great believer in women, and their duty (as well as their right) to share in public life.

“You must meet the Fenian leader, John O’Leary,” said Oldham. “I’ll take you to a meeting of the Contemporary Club—O’Leary usually attends.”[7]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Houses of Parliament from the river, London, England. England London, ca. 1890. [Between and Ca. 1900] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002696921/.

[2] Houses of Parliament, St. Stephen’s Hall Interior, London, England. England London, ca. 1890. [Between and Ca. 1900] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002696922/.

[3] Gonne left Kingston, Ireland for England on September 18, 1888. She was back in Ireland by the first week of October 1888. Her meeting with Davitt, presumably, occurred within this window of time. “Court and Fashion.” The Irish Times. (Dublin, Ireland) September 18, 1888

[4] “The Cannibal Story.” The Bolton Evening News. (Lancashire, England) November 12, 1890.

[5] “Miscellaneous Items.” The Brewer’s Guardian. Vol. XIX, No. 482 (April 2, 1889): 108; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2506. (website file: 1A:1875-1885) I. Agnes Jameson. [11/10/83]

[6] “Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language.” The Dublin Weekly Nation. (Dublin, Ireland) October 13, 1888.

[7] MacBride, Maud Gonne. A Servant of The Queen: Reminiscences. Victor Gollancz. London, England. (1938): 87-89.