NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS

ACT II.

IV.

⸻

~

After Olcott’s arrival at London a circular was issued to each registered French member, appointing a time and place of meeting in Paris. He was accompanied by an “austere gentleman” named Richard Harte, a former New York newspaperman of Irish extraction, and old friend of Olcott who joined the Society in 1878.[1] Living in London in the 1880s, Harte acquired “considerable reputation” among Theosophists as the writer of a famous editorial in Lucifer (December 1887,) entitled “Lucifer to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Greeting!” and also for his work as Secretary of the Theosophical Publishing Society.[2] Harte was going to India in October as Olcott’s editorial associate on The Theosophist, replacing Cooper-Oakley, (editor of volumes VI-IX,) who resigned with Subba Row.[3] Judge arranged with the Executive Committee (of the American Council) to also have Harte represent them as the American delegate for the upcoming Convention in Adyar. [4]

On September 17th, Olcott’s formal decision regarding the “Paris imbroglio” was read before the assembly. The impossibility of reorganizing the Isis T. S. being evident, a new Charter was granted to a new Branch, the Hermes T.S., with the well-known author, Arthur Arnould, elected as President. The decision threw Gaboriau “out of the active running,” and caused him and some of his followers to denounce Olcott.[5]

Olcott and Harte returned to London, where a meeting was held on the September 27, 1888, for the purpose of confederating the European Branches into one Council.[6]

9 Conduit Street.[7]

On October 6, Olcott sent Harte to Cambridge as his special representative to preside over the inaugural meeting of the “Cambridge Theosophical Society.”[8] Olcott, meanwhile, called a Theosophical Society to consider proposals which he had previously forwarded to them regarding the formation of a British Section of the Theosophical Society.

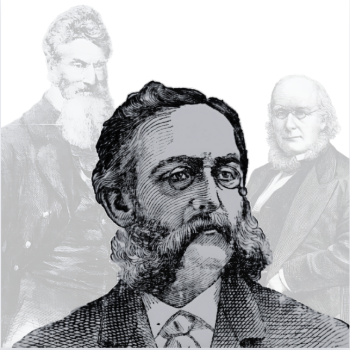

Alfred Percy Sinnett (Wiki Commons)

An influential old member, A.P. Sinnett, was invited to the meeting, but he was hardly supportive of the proposal. Perhaps no one outside of Blavatsky was more influential to Theosophical cosmology than Sinnett, in the early days at least. He met Olcott and Blavatsky in India while he was an editor for a leading English daily called The Pioneer. He recorded his experiences with Blavatsky’s mystical phenomena in his book, The Occult World (1881) One phenomenon in particular caught the attention of the public eye—the manifestation of a teacup and saucer from seemingly out of nowhere.[9] In 1883 Sinnett published Esoteric Buddhism, in which he introduced the concept of “root races” to Theosophy, as well as the idea of the “Akashic Records” (also referred to as the “Akashic Library” or “Astral Records.”)[10] Sinnett and his wife, Patience, returned to England in 1883, where both joined the London Lodge. By the fall of 1883, the London Lodge split into two factions, one lead by Sinnett, and the other by Anna Kingsford. (In 1884 Kingsford’s Branch would evolve into a separate body, the Hermetic Society.)[11] For a few years Sinnett’s London Lodge was the only Theosophical center in England. That changed when Blavatsky arrived in 1887, and twelve members of the London Lodge left to form the Blavatsky Lodge, led by Blavatsky herself. This created something of a rivalry.[12]

Despite Sinnett’s disapproval of the British Section, the decision for its creation was passed on October 8, 1888, in a meeting at the headquarters of the Royal Institute of British Architects, 9 Conduit Street. Dr. Arch Keightley was appointed General Secretary pro tem. A Committee consisting of Olcott, Sinnett, Arch, and others, was subsequently formed to draft a code of Rules to be submitted and decided upon at a later date.[13]

Theosophists around the world were growing concerned that a fissure was developing in the highest strata of leadership. To refute the “many falsehoods spread by third parties who wanted to breed dissension” between Blavatsky and Olcott, “or give the impression that the Society was on the point of splitting,” Blavatsky and Olcott then issued a joint note:

London, October 1888.

To dispel a misconception that has been engendered by mischief-makers, we, the undersigned Founders of the Theosophical Society, declare that there is no enmity, rivalry, strife, or even coldness between us, nor ever was, nor any weakening of our joint devotion to the Masters or to our work, with the execution of which they have honored us. Widely dissimilar in temperament and mental characteristics and differing sometimes in views as to methods of propagandism, we are yet of absolutely one mind as to that work. As we have been from the first, so are we now united in purpose and zeal, and ready to sacrifice all, even life, for the promotion of Theosophical knowledge, to the saving of mankind from the miseries which spring from ignorance.

H. P. Blavatsky

H. S. Olcott.[14]

The day after the creation of the British Section (October 9, 1888,) the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society was established.[15] A notice in Lucifer provided a mission statement which read:

THE ESOTERIC SECTION OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY.

Owing to the fact that a large number of Fellows of the Society have felt the necessity for the formation of a body of Esoteric students, to be organized on the original lines devised by the real founders of the T. S., the following order has been issued by the President-Founder (Olcott):—

- To promote the esoteric interests of the Theosophical Society by the deeper study of esoteric philosophy, there is hereby organized a body, to be known as the “Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society.”

- The constitution and sole direction of the same is vested in Madame H. P. Blavatsky, as its Head; she is solely responsible to the Members for results; and the section has no official or corporate connection with the Exoteric Society (the Theosophical Society) save in the person of the President-Founder (Olcott.)

- Persons wishing to join the Section, and wiling to abide by its rules, should communicate directly with: ):—Mme. H. P. Blavatsky, 17 Lansdowne Road, Holland Park, London, W.

(Signed) H. S. Olcott, President in Council.

Attest:—H. P. Blavatsky.[16]

Those members of the Theosophical Society who were interested in joining, were sent a copy of preliminary Rules, and the Pledge:

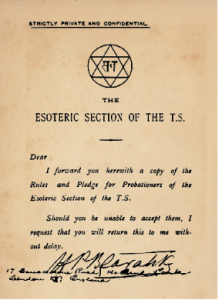

“The Esoteric Section of the T.S.”

Strictly Private and Confidential.

THE ESOTERIC SECTION OF THE T.S.

I forward you herewith a copy of the Rules and Pledge for Probationers of the Esoteric Section of the T.S.

Should you be unable to accept them, I request that you will return this to me without delay.

E.S.T. Probationary Rules.

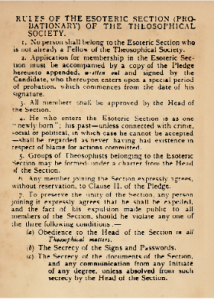

RULES OF THE ESOTERIC SECTION (PROBATIONARY) OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY.

- No person shall belong to the Esoteric Section who is not already a Fellow of the Theosophical Society.

- Application for membership in the Esoteric Section must be accompanied by a copy of the Pledge hereunto appended, written out and signed by the Candidate, who thereupon enters upon a special period of probation, which commences from the date of his signature.

- All members shall be approved by the Head of the Section.

- He who enters the Esoteric Section is as one “newly born”; his past—unless connected with crime, social or political, in which case he cannot be accepted—shall he regarded as never having had existence in respect of blame for actions committed.

- Groups of Theosophists belonging to the Esoteric Section may he formed under a charter from the Head of the Section.

- Any member joining the Section expressly agrees, without reservation, to Clause II of the Pledge.

- To preserve the unity of the Section, any person joining it expressly agrees that he shall be expelled, and the fact of his expulsion made public to all members of the Section, should he violate any one of the three following conditions: (a) Obedience to the Head of the Section in all Theosophical matters. (b) The Secrecy of the Signs and Passwords. (c) The Secrecy of the documents of the Section, and any communication from any initiate of any degree, unless absolved from such secrecy by the Head of the Section.

E.S.T. Pledge.

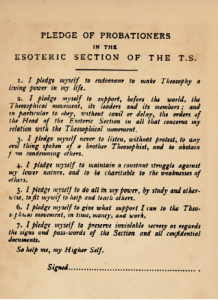

PLEDGE OF PROBATIONERS IN

THE ESOTERIC SECTION OF THE T.S.

- I pledge myself to endeavor to make Theosophy a living power in my life.

- I pledge myself to support, before the world, the Theosophical movement, its leaders, and its members; and in particular to obey, without cavil or delay, the orders of the Head of the Esoteric School Section in all that concerns my relation with the Theosophical movement.

- I pledge myself never to listen, without protest, to any evil thing spoken of a brother Theosophist, and to abstain from condemning others.

- I pledge myself to maintain a constant struggle against my lower nature, and to be charitable to the weaknesses of others.

- I pledge myself to do all in my power, by study and otherwise, to fit myself to help and teach others.

- I pledge myself to give what support I can to the Theosophical movement, in time, money, and work.

- I pledge myself to preserve inviolable secrecy as regards to the signs and passwords of the Section and all confidential documents.

So help me, my Higher Self.

Signed __________________________

On sending in their signed Pledges, each Candidate would be “tested,” on the inner planes, by the Master. That is, their past lives would be called up, and depending upon what was seen there (and known of their real selves,) one would be accepted, or denied, as a candidate.[17]

~

On October 10, 1888, Olcott spent the afternoon with Professor Max Müller in Oxford. There he was introduced to the anthropologist, E.B. Tylor, and the Indologist, Sir William W. Hunter.[18] Müller’s Gifford Lectures at Edinburgh were just weeks away, and the conversation centered on religion, and the study of religion.

The newspapers were stating that despite the “aid given to the Buddhistic faith by the prevalence of Theosophy in England,” the growth of Buddhism was “so slight that it [could] scarcely be taken into account.”[19]

Despite these reports, Hunter was of a different mind regarding the future religiosity of the Empire—particularly India.

“There are new forces at work in India shaping the religious conceptions of the people,” said Hunter. “I venture to say that a new religion will soon arise in India. The Christian Missions, admittedly, are among the most powerful factors in India, however, I do not think this ‘new religion’ will be like our modern Christianity.”[20]

7 Norham Gardens, Oxford, England. (Home of Max Müller.)[21]

Olcott was pleased to find the men “cordially interested” in the branch of the Society’s work represented by the Adyar Library (under Pandit Bhāshyāchārya,) Tukaram Tatya’s Bombay Theosophical Publication Fund, and the broad network of Theosophical publishing in general.[22]

One of the topics circulating in the press was Richard Harte’s reprint of The Hebrew Talisman. “A satire on Jewish capitalists,” the work was originally published in 1836, “just after the death of old Rothschild.” As the St. James Gazette stated: “It affected to be the work of the Wandering jew; and described his adventures with certain of his mortal coreligionists, whom he made rich on condition that they plundered the Gentile and intrigued for the restoration of Judea, but who invariably threw him overboard as soon as their pockets were filled.” Though the brochure “provoked much laughter in its day,” Harte believed that it was “an important but neglected contribution to the literature of Occultism,” and published it under the auspices of the T.P.S.[23] Harte, no doubt, was aware of the growing tide of Jewish immigrants to Palestine (as noted in the newspapers that summer,) as his interpretation of the work suggests as much.[24] With the anti-semitic fervor sweeping over London after the Whitechapel murders, the work was probably not received in the manner in which Harte wished. (There were many Jewish members of the Theosophical Society, even “capitalists.” The philanthropist, Baron Maurice de Hirsch, owner of the new Orient Express, was a member of the Society, but “he contrived to keep it pretty dark during his life.”)[25]

“Oriental reprinting, translation, and publishing portion of the Society’s work is noble, there could be no two opinions about it, nor are there among Orientalists,” said Müller. “As I stated in my letter to you, Colonel, if the Theosophical Society means to do any real good, it must take its stand on the Upanishads, and on nothing else. A beautiful and correct edition of the text seems to me almost a duty to be performed by the Theosophical Society.”[26]

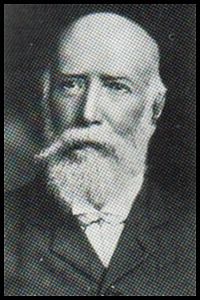

Max Müller.[27]

Olcott and Müller retired to the library, where the walls were covered with bookcases brimming with the choicest texts of ancient and modern scholarship. Müller took a seat in his morocco-covered mahogany writing-table. Olcott, wearing his “funny blue spectacles,” sat facing the fireplace (at the nearer end of the table.) On the hearth were two marble statuettes of the Buddha sitting in meditation, taken from the great Temple of Rangoon.

“The Buddhists are very sensitive about such things,” said Olcott, “and a painful impression would be made upon the mind of any sincere person of that faith, if he should call at your house and see them in your fireplace.”

“With the Greeks, the hearth was the most sacred spot,” said Müller authoritatively. He then softened his tone. “Colonel, I implore you, pivot from this evil course of Theosophy. Focus on the official scholarship. You have done nobly in helping so much to revive the love for Sanskrit, and the Orientalists have watched the development of your Society with the greatest interest from the commencement. But why, why, do you insist on spoiling all this good reputation by pandering to the superstitious fancies of the Hindus! Telling them that there is an esoteric meaning in their Shastras? My good man, I know the language perfectly! I assure you there is no such thing as a ‘Secret Doctrine’ in it.”

“Professor Müller, your conclusions as to these occult things are at variance with the beliefs of every orthodox pandit, from one end of India to the other,” said Olcott. “The Gupta Vidya is a recognized element in Hindu religious philosophy, as, of course, you well knew. What most draws the educated Indians into sympathy with us was is the very fact that we believed exactly what they had believed from time immemorial on these subjects. Moreover, I would venture to declare to the Professor that I had had the clearest evidence, at first hands, that the Siddhas, or Mahatmas, live and work for humanity today as they ever have. The claims of Patanjali as to the Siddhis, and the possibility of developing them, are, to my certain knowledge, true.”

Müller’s face turned red, and his nostrils dilated. “Well, then, we had better change the subject.” The topic was changed, but Müller soon returned to the subject. “Colonel Olcott, with all your fine ideas for doing good how can you lend yourself to that nonsense of broken teacups and so on? We know all about Sanskrit and Sanskrit literature and have found no evidence anywhere of the pretended esoteric meaning which your Theosophists profess to have discovered in the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Indian Scriptures: there is nothing of the kind, I assure you. Why will you sacrifice all the good opinion which scholars have of your legitimate work for Sanskrit revival to pander to the superstitious belief of the Hindus in such follies?”

“All religions,” replied Olcott, looking down through his spectacles, “must be manured.”[28]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 174. (Website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Richard Harte. (1/12/78); Pusey-Keith, Alfred. “Mr. Richard Harte,” Light. Vol. XXIII, No. 1,156. (March 7, 1903): 111.

[2] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 6. (September 1888): 203-204.

[3] Olcott, H.S. “Editorial Change.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. No. 110. (December 1888): xxvii-xxviii.

[4] “Notes.” The St. James Gazette. (London, England) October 18, 1888; Anon. The Theosophical Movement: 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 233.

[5] Olcott, Henry Steel. “Old Diary Leaves: Fourth Series, chapter IV.” The Theosophist. Vol. XXI., No. 5. (February 1900): 257-265.

[6] “Theosophical Activities.” The Path. Vol. III., No. 7. (October 1888): 235-236.

[7] Royal Institute of British Architects. International Congress on Architectural Education, 28 July to 2 August 1924: Proceedings. Royal Institute of British Architects. London, England. (1925): Frontispiece.

[8] “Cambridge Theosophical Society.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. IX. No. 110. (December 1888): xxix.

[9] Sinnett writes: “Concerning this some joking arose over the fact that we had one cup and saucer too few, on account of the seventh person who joined us at starting [the picnic,] and some someone laughingly asked Madame Blavatsky to create another cup and saucer. There was no set purpose in the proposal at first, but when Madame Blavatsky said it would be very difficult, but that if we liked she would try attention was of course at once arrested. Madame Blavatsky, as usual, held mental conversation with one of the Brothers [Masters,] and then wandered a little about in the immediate neighborhood of where we were sitting—that is to say, within a radius of half a dozen to a dozen yards from our picnic cloth—I closely following, waiting to see what would happen. Then she marked a spot on the ground and called to one of the gentlemen of the party to bring a knife to dig with. The place chosen was the edge of a little slope covered with thick weeds and grass and shrubby undergrowth. The gentleman with the knife—let us call him X—as I shall have to refer to him afterwards—tore up these in the first place with some difficulty as the roots were tough and closely interlaced. Cutting then into the matted roots and earth with the knife, and pulling away the debris with his hands, he came at last, on the edge of something white which turned out, as it was completely excavated, to be the required cup.” [Sinnett, A.P. The Occult World. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, & Co. Ltd. London, England. (1895): 46-47.]

[10] ROOT RACES: “The periods of the great root races are divided from each other by great convulsions of Nature and by great geo logical changes […] Seven great continental cataclysms occur during the occupation of the earth by the human life-wave for one round period. Each race is cut off in this way at its appointed time, some survivors remaining in parts of the world, not the proper home of their race; but these, invariably in such cases, exhibiting a tendency to decay, and relapsing into barbarism with more rapidity. [Sinnett, A.P. Esoteric Buddhism. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1893): 105.] AKASHIC RECORD: “Early Buddhism then clearly held to a permanency of records in the Akasa.” [Sinnett, A.P. Esoteric Buddhism. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1893): 127.]

[11] Sinnett, A.P. The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe. Theosophical Publishing House, Ltd. London, England. (1922): 23-29, 41, 51-57.

[12] Cleather, Alice Leighton. H. P. Blavatsky As I Knew Her. Thacker, Spink & Co. Calcutta, India. (1923): 8-10.

[13] “Theosophical Activities.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 14 (November 15, 1888): 260-263.

[14] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 65.

[15] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 60.

[16] “The Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society.” Lucifer. Vol. III, No. 14 (November 15, 1888): 263.

[17] Cleather, Alice Leighton. H. P. Blavatsky As I Knew Her. Thacker, Spink & Co. Calcutta, India. (1923): 15-16.

[18] “The President’s Tour.” Supplement To The Theosophist. Vol. X (December 1888): xxvi-xxvii.

[19] “Faiths of the World.” The Lancashire Evening Post. (Lancashire, England) October 12, 1888.

[20] “A New Religion.” The Aberdeen Free Press. (Aberdeenshire, Scotland) December 20, 1888.

[21] Müller (née Grenfell,) Georgina Adelaide ed. The Life And Letters Of The Right Honourable Friedrich Max Müller In Two Volumes: Vol. I. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1902): 335.

[22] “The President-Founder’s Address.“ General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 2-13.

[23] “Notes.” The St. James Gazette. (London, England) October 18, 1888.

[24] In the Spring of 1888, the St. James’s Gazette stated: “It used to be said, not so long ago, that there were more Jews in London than in Jerusalem. The Hebrew population of the metropolis is still growing; but it may be doubted whether it is increasing nearly so rapidly in proportion as that of Jerusalem. In 1880 there were only about 5,000 Jews in the ancient city of Israel; now, it is reported, there are more than 30,000. This large increase is very curious, since it is not to be supposed that the multiplication of means of livelihood has kept pace with the immigration. Jerusalem has been, and long must remain, a very poor city, and most of the immigrants who have been flocking to it of late years belong to the poorer classes. The recent persecutions in Russia are said to account for the bulk of this unexpected increase, which is still continuing in much the same proportion. Doubtless, however, many of the Jews who have returned to the ancient capital of their race have gone from Germany, where matters have assuredly been exceedingly uncomfortable for them for considerable time past.” [“Notes.” St. James’s Gazette. (London, England) May 21, 1888.]

In the introduction to The Hebrew Talisman, Harte writes: “The present number of the T.P.S. pamphlets, a reprint of a curious and very rare work, may not appear to some readers to have a very direct bearing on theosophical teachings. Those who have got beyond the A B C of Theosophy, however, will find in this issue a good deal of material for serious thought. It deals with one of the most puzzling and deeply interesting problems which the past has left for solution to the future—the destiny of the Jewish race, and the fate of the Holy Land. The plot of the work (if that expression be allowed) is based upon two ideas, which taken singly are so well known as to be almost tiresome; namely, the ancient belief of the Jews, based upon prophecy and national pride, that eventually they will recover possession of Judea, and gather together once more at Jerusalem, after their long exile from the land of their ancestors—a belief only less intense than the longing for its realization. The other idea is that contained in the legend of the Wandering Jew—firmly believed in by all Christendom from the apostolic ages until but recently, still half-believed by millions, and to which the doctrine of reincarnation, especially immediate reincarnation for a specific purpose, lends, if not plausibility, at least a new intellectual interest. These two ingredients of the plot when put together enter, as it were, into chemical combination, for they give rise to an idea which differs in its characteristics from both of the components. As a punishment for a thoughtless word spoken by a foolish and ignorant mortal even to a god (in disguise at the time), the eternal and miserable activity of the Wandering Jew is a purposeless piece of unworthy revenge, as little credible in this more humane and enlightened age as the miracle required to consummate it. As a practical settlement of the Jewish question, the return of the Hebrew nation, or even a considerable part of the Jews, to Syria seems patently absurd. All travellers describe the Holy Land as barren and poor in the extreme, a land which, if it ever flowed with “milk and honey,” has for centuries been believed to have withered under the terrible curse of an angry God. Could anyone but a child imagine for one instant that so thoroughly practical a people as the Jews, a race, moreover, pre-eminently fond of the luxuries of life, would voluntarily abandon the various countries which for centuries have been their homes, abandon their hereditary occupations, abandon civilization, and undertake the frightful labour of reclaiming a rocky and arid district, a labour from which even back-woods pioneers inured to hardship would shrink—and all for a religio-sentimental idea? But put these two incredible notions together, and all is changed. What if it be the mission of the so-called Wandering Jew to preserve in the Hebrew mind the recollection of the former glories of the race, and to keep alive the longing once more to revive them? The moment that idea finds entry to the mind, the legend ceases to be childish, and the longing is no longer unaccountable. The two things explain each other, and taken together they raise the Jewish question to a level far above that occupied by the superstitions of the ignorant, or the calculations of individual self-interest. To the Jew himself it is no less than the finger of Jehovah that becomes manifest from this larger point of view. Through all the centuries, as they believe, He has been disciplining and preparing them for their final triumph. Already the despised outcasts of a thousand years ago are the masters of kings and republics alike. There are a score of Jews today each one of whom is a greater power in the world than an army of a hundred thousand men. Were they to combine they could purchase Palestine ten times over, and then keep a million of Christian workmen joyfully slaving at starvation wages for twenty years in doing the work of making the country once more a garden while they stood by to superintend. Perhaps the Jews are right. It may be that the finger of Jehovah is guiding their destinies in the direction of Jerusalem. We know that to be worshipped there, and by them alone, was once His greatest glory. Far be it from theosophists to deny that such may still be the case, and if it so be, then, for the Jews themselves, all that need be done to complete his purposes will be accomplished. To the theosophist, however, Jerusalem, even Judea, is not the whole of this earth, nor this earth the whole Universe. And a higher guidance than that by human will in the case of the Jews, does not imply a monopoly of divine solicitude for one little tribe of people, nor a monopoly of power and wisdom for the celestial being who has chosen them for his special favour. If it be true that the affairs of the Jewish race are under higher guidance, then logic and justice require us to believe that a similar guidance is vouchsafed to all mankind, and to the inhabitants of the myriad worlds that roll in space. Is it so? Is there being enacted before our eyes a tremendous drama of creation, in which individual men are as microscopic animalculi? Does it get rid of the idea of a directing power to call “spontaneous development” what our ancestors, equally ignorant, called Divine Providence? Who is to ask these questions? And of whom can they be asked? Will the Christian listen for their answer from the mouth of a Jew? Will a theosophist seek it from a theologian? Will those who know go to school to those who invent fables? Above, behind, inside of every material thing there is a great, an eternal, incomprehensible, sustaining power—absolute and impersonal, the Divine Spirit. Far lower in the scale of existence there are powers, personal and non-eternal, creatures who had a beginning and will have an end. Men call these lower fashioning powers collectively a personal God; not only jumbling them together, but confounding them with the unknowable Absolute. Is one of these minor powers, the Jehovah of the ancient Hebrews, now pulling the wires that attach his people to him, and turning their steps towards the “promised land” once more? It is said that wealthy Jewish bankers have at this moment actual legal right of possession to Palestine, holding it in mortgage from the Sultan. It is said that Jewish statesmen have arranged for the completion and ratification of the transfer of the property to the mortgagees, upon the fulfilment of certain diplomatic conditions which events are rapidly bringing about. At the present moment a large part of Palestine, and nearly the whole of Jerusalem, is said to be owned by Jews. What does it all mean? The T.P.S., in republishing this little work, disclaims all political purpose, as needs hardly to be said. It contains some bitter sayings concerning people long since dead, and events now almost “ancient history,” all of which the T.P.S. would gladly have omitted in the reprint, had it not been that to do so would have spoiled the consecutiveness of the argument or narrative therein contained. From internal evidence the Hebrew Talisman was written about 1836. No one ever discovered who the writer was. The edition was soon exhausted, and till now has never been reprinted.” [Harte, Richard (ed.) The Hebrew Talisman. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1888): Introduction.]

[25] During the 1896 Convention of the Theosophical Society in America, it was stated: “A number of resolutions were read, one of which hailed the late-Baron de Hirsch as a true Theosophist (he contrived to keep it pretty dark during his life,) and called for the placing of his picture in place of honor at headquarters.” [“An Occult School To Be Founded Here.” The New York Journal. (New York, New York) April 27, 1896.] It is possible that Hirsch was the wealthy friend whom J.D. Buck mentions sponsored the publication of Vol. II of The Path. [Buck, J. D. “His One Ambition.” Theosophy. Vol. XI., No. 2. (May 1896): 41-43.] This would be sympathetic to the ethos of Hirsch’s views on Philanthropy: “In relieving human suffering I never ask whether the cry of necessity comes from a being who belongs to my own faith or not…” [Baron de Hirsch. “My Views On Philanthropy.” The North American Review. Vol. CLIII, No. 416. (July 1891): 1-4.]

[26] Müller, F. Max. “The Theosophical Society’s Publication Fund.” The Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 111. (December 1888): 143.]

[27] Müller (née Grenfell,) Georgina Adelaide ed. The Life And Letters Of The Right Honourable Friedrich Max Müller In Two Volumes: Vol. II. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1902): Frontispiece.

[28] “The President’s Tour.” Supplement To The Theosophist. Vol. X (December 1888): xxvi-xxvii; Müller (née Grenfell,) Georgina Adelaide ed. The Life And Letters Of The Right Honourable Friedrich Max Müller In Two Volumes: Vol. II. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1902): 234, 294; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume III. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 177-178; Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume IV. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1910): 57-58; Child-Villiers, Margaret Elizabeth Leigh. Fifty-One Years Of Victorian Life. John Murray. London, England. (1922): 146.